Lynn Margulis said that Richard Dawkins is “arrogant” and “solipsistic”. Richard Dawkins, in turn, said that Margulis is an “extremely obstinate” person who “doesn’t listen to argument”. These are just two examples among many in one single book. This helps show us that (nearly?) all scientists are emotional creatures (just like us) — often with both fragile and large egos. They also hold strong political and moral views. Arguably, those views sometimes impinge on their science. And that’s precisely why the distinction between science and scientists must be made.

“Science is politics by other means.”

— Sandra Harding, from her book Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?

Science is science.

And scientists are scientists.

Of course you can’t have science without scientists. Yet, in broad terms, it can still be said that science is an abstraction from the work of all individual scientists.

So it’s wise not to confuse what an individual scientist states— or believes — with science itself.

This basically means that Stephen Hawking isn’t theoretical physics. Michael Mann and James Hansen aren’t climatology. (Richard Lindzen and Freeman Dyson aren’t climatology either.) Richard Dawkins isn’t evolutionary biology or Darwinism. (Stephen Jay Gould isn’t evolutionary biology or Darwinism either.) Anthony Fauci isn’t immunology or medical science. Steven Pinker isn’t evolutionary psychology. Brian Cox and Nigel DeGrasse Tyson aren’t the whole of science.

To state the obvious: scientists are human beings. And, like all human beings, they are emotional creatures who also have strong political and moral views. Not only that: those views sometimes impinge on their science…

And that’s precisely why the distinction between science and scientists must be made.

It’s also worth making a distinction here between the following:

(1) Those scientists who use science (or specific scientific theories) to advance their prior political goals, values and ideologies.

(2) Those scientists who believe that science itself is always political (i.e., regardless of the specific goals, values and ideologies of particular scientists).

Of course there can be much overlap between (1) and (2).

Sandra Harding (quoted at the top), for example, believes that science itself is (aways) political. In that, she’s following the footsteps of Soviet agronomist and biologist Trofim Lysenko (1898–1976), who divided science into “bourgeoise science” and “proletarian science”. (Interestingly, Lysenko too had a problem with the Darwinian notion of competition — see later sections.) And Harding herself speaks of “gendered science” and “white male science”.

However, all the scientists featured in this essay (except for Brian Goodwin) wouldn’t say that science itself is always political (although they may say that science can be political). However, it can be argued that some scientists do use their scientific theories to advance their prior political goals and values.

In terms of the following essay itself.

John Brockman’s The Third Culture

Virtually all the quotes in this piece are taken from The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution. This book was edited by John Brockman, who also wrote the introductions to all the individual chapters.

Brockman also runs the Edge Foundation website, in which the header reads:

“To arrive at the edge of the world’s knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves.”

Wikipedia also tells us that in The Third Culture “leading scientists and thinkers contribute their thoughts in plain English”.

More relevantly, the interesting thing about Brockman’s The Third Culture is how clear, open and honest the scientists within it are (hence the words “plain English”). It can also be assumed that this clarity and honesty was due to the simple fact that the book’s contents contain the transcripts of various taped interviews with the featured scientists. In other words, this isn’t the kind of stuff you’d read in academic papers or even in popular- science books.

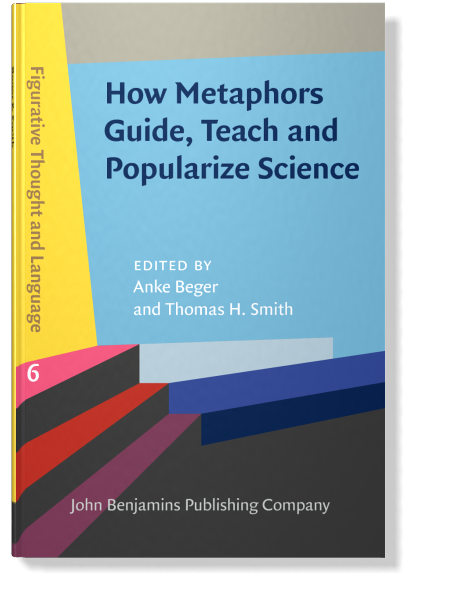

Scientific Metaphors (Such as “the Selfish Gene”)

Of course it may be (or actually is) the case that metaphors are of vital importance in science — and not only to help laypersons understand matters. It must also be acknowledged that scientists get annoyed when others — especially philosophers — pick up on their use of metaphors and other poorly-defined terms. (Such critics have been accused of conceptual conservatism.) One also needs to decipher how aware the scientists discussed are of the metaphorical nature of the words (or phrases) they use. Indeed it also needs to be asked if such scientists take these words (or phrases) to be metaphors at all!

Take Richard Dawkins’ well-known phrase “the selfish gene”.

These words are extremely problematic.

The simple argument in this essay is that genes are neither selfish nor not selfish.

So let’s rewrite a passage from the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) in which the word “genes” is substituted for Spinoza’s own word “nature”:

I would warn you that I do not attribute to genes either selfishness or cooperativeness. Only in relation to our imagination can genes be called selfish or cooperative.

Of course the phrase “the selfish gene” has been debated to death. And Dawkins has himself stressed its metaphorical nature (see here).

Yet if you take away the phrase’s metaphorical content, readers may wonder what, precisely, is left.

Nature: Gaia vs Hell

In John Brockman’s The Third Culture, the Gaia hypothesis is discussed by various scientists. Those scientists include G.C. Williams, Lynn Margulis, Richard Dawkins and Brian Goodwin.

Let’s begin with the American biologist George Christopher Williams (1926–2010).

G.C. Williams puts the boot into fellow biologist Lynn Margulis (1938–2011) in the following manner:

“[] I would say that Lynn Margulis is very much afflicted with a kind of ‘God-is-good’ syndrome, in that she wants to look at nature and see something benign and benevolent and ultimately wholesome and worth having [].”

The obvious riposte to that passage is to state that very similar things could have been said about G.C. Williams himself. Indeed Williams actually admitted that! That is, he said that

“[Margulis] could say the same about me — that I think ‘God is evil,’ and I look out there at His creations and see nothing but evil”.

Perhaps Margulis would have been right to do so. After all, Williams also talked about nature being (although quoting Tennyson) “red in tooth and claw”.

Yet what if nature is neither “benign and benevolent” nor “red in tooth and claw”? Perhaps Spinoza was right after all.

In any case, G.C. Williams continued on the same theme:

“[Margulis] likes to look out there and see cooperation and things being nice to each other. This culminates in this Gaia idea. [] But that’s what she wants to see, and therefore, come what may, that’s what she’s going to see.”

Of course Williams might well have been purely metaphorical and/or rhetorical when he used the words “red in tooth and claw” and even when he talked about “competition”. (Obviously, Tennyson’s poetic phrase is a metaphor.) But so too might Margulis when she said the things she said.

So does all this simply mean that this is only a debate about which metaphors scientists should use and how they should use them? In that case, then, where does the anger and sarcasm come from (i.e., as displayed in The Third Culture)?

Ironically enough (i.e., considering G.C. Williams’s take on Margulis), even James Lovelock’s friend — i.e., Margolis herself — admitted that Lovelock had political (or perhaps moral) motivations when it came to his own Gaia theory.

In detail, Margulis stated the following:

“Lovelock’s position is to let the people believe that Earth is an organism, because if they think it is just a pile of rocks they kick it, ignore it, and mistreat it. If they think Earth is an organism, they’ll tend to treat it with respect. To me, this is a helpful cop-out, not science.”

This basically means that what G.C. Williams accused Margulis of (in the quoted passage a few moments ago), Margulis accused Lovelock of (in the passage directly above).

The passage from Margulis is also odd because it’s basically saying that Lovelock was dishonest and/or insincere. That is, Lovelock didn’t actually (or really) believe that the Earth is an “organism” at all. Instead, he simply wanted “to let the people believe [my italics] that Earth is an organism”.

So why did Lovelock want people to believe that?

He wanted people to believe that Earth is an organism because he believed that if this noble lie (or “lie for Justice”) wasn’t peddled by scientists such as himself, then — most? all? — people would think that the Earth is “just a pile of rocks”. And if people thought that, then “they [would] kick it, ignore it, and mistreat it”.

[This way of looking at things was replicated by the mathematician and sci-fi novelist Rudy Rucker, who’s also a panpsychist. In another book edited by John Brockman, Rucker stated the following: “If the rocks on my property have minds, I feel more respect for them in their natural state. If I feel myself among friends in the universe.”]

So if Lovelock was indeed being dishonest and/insincere when he argued that Earth is an “organism”, then it’s not surprising that Margulis should have continued by saying that Lovelock’s position is a “helpful cop-out, not science”.

Yet even here Margulis is still buying into Lovelock’s noble lie (or “pious fiction”) in that she also argued that it’s “helpful”. That said, even though this noble lie (i.e., about Earth being an organism) just happens to be helpful; then that still doesn’t stop it from also being a “cop-out” that’s “not science”.

This simply raises the question: Did Lovelock believe that the Earth is an organism or not?

Ironically enough, the evolutionary biologist and author Richard Dawkins (Margulis’s scientific and personal foe) seems to be (kinda) in tune with Margulis here. That said, one wonders if Dawkins was being rhetorical (a word he uses against his opponents in Brockman’s book) when he stated that Gaia theorists believe that

“there will be some gas produced by bacteria which is good for the world at large and so the bacteria go to the trouble of producing it, for the good of the world”.

Do Gaia theorists really believe that bacteria have the good of the world in mind when they produce a certain gas?

Again, perhaps it’s just a metaphor.

Indeed the palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould once argued that Gaia hypothesis itself is “a metaphor, not a mechanism”. That is, the very name and heart of Gaia is metaphorical (i.e., not only the claims and terms used within the theory itself). That said, the ecologist David Abram responded by arguing that Stephen Gould didn’t seem to realise that the word “mechanism” is itself a metaphor — just one which happens to have lost its metaphorical (as it were) ambience. (See David Abram here.)

However, if it’s just a metaphor (as Lynn Margulis herself hinted), then what would be left of the Gaia hypothesis once stripped of its metaphors; and, therefore, its political (or moral) affiliations and ramifications? Would this be a case of unweaving the rainbow that is the Gaia hypothesis?

Despite Margolis’s words of warning about Lovelock’s romantic(?) take on Gaia, it’s ironic that the American philosopher Daniel Dennett (just like G.C. Williams) accused Margulis of (more or less) the same thing she accused Lovelock of.

Dennett stated:

“Some of her recent popular writing disturbs me, because I think she’s trying to take that wonderful idea and harness it as a political idea, stressing cooperation over competition. Yes, the eukaryotic revolution was an instance in which what began as competition evolved into what is fundamentally a cooperative arrangement.”

However, Dennett continued:

“[B]ut precisely what it doesn’t show is that cooperation is the norm or that cooperation is always good or that it’s always possible. It’s the rare and wonderful thing that enabled multicellular life to take off. But you can’t read into it any message such as that nature is fundamentally cooperative; it isn’t.”

As some readers will probably guess, the traffic wasn’t all one way on this issue.

Despite that seeming concordance between Margulis and Dawkins (mentioned earlier) on Lovelock’s Gaia, Margolis also attacked Dawkins (also in relation to Gaia) when she stated the following:

“That quote captures the arrogance of Dawkins. [] He prefers to take potshots instead of actually discussing the details of Gaia. When he says that Gaia is ‘dangerous and distressing to scientists who value the truth,’ he’s talking about himself. Gaia is dangerous and distressing to him because, unlike the rest of us, HE values the truth. The inference of his statement simply exposes his solipsism.”

As stated, this is odd when bearing in mind what Margulis herself said about Lovelock.

So does this mean that, firstly, there’s Margulis’s Gaia; and then there’s Lovelock’s Gaia?

That could have meant that Margulis was stating that Dawkins is arrogant and solipsistic only when it came to her own take on Gaia, not Lovelock’s.

In any case, Richard Dawkins returned the favour here:

“I first met Lynn some years ago at a conference in the South of France, and I think we got on rather well together. I have since, when I’ve met her, found her extremely obstinate in argument. I have the feeling that she’s the kind of person who just knows she’s right and doesn’t listen to argument. [] [I]n the case of the theory of the origin of the eukaryotic cell, she was right to be obstinate. She’s turned out, probably, to be right, but that doesn’t mean she’s always right. And I suspect that she isn’t always right.”

Well, that’s the personal stuff out of the way.

What about Margulis’s actual scientific theories? Dawkins continued:

“Some of her recent popular writing disturbs me, because I think she’s trying to take that wonderful idea and harness it as a political idea, stressing cooperation over competition.”

Of course “stressing” competition is just as bad.

Again, it can be argued (à la Spinoza) that neither cooperation nor competition exist in nature — at least not in the sense that these things exist in the world of socialised and intelligent human beings.

Yet if these words and phrases are “only metaphors”, then surely they’re… only metaphors.

And this is where the prior politics of scientists often slips in.

Politics and Scientific Metaphors

The following sums up the problems discussed so far:

(1) There have been scientists (along with political activists on the periphery) who’ve stressed — for political reasons - competition and ignored (or simply played down) cooperation.

(2) And then there have been scientists (along with political activists on the periphery) who’ve stressed — for equally political reasons — cooperation and ignored (or simply played down) competition.

The simple and obvious thing to do here, then, would be to stress both cooperation and competition!

However, one other option (as already mentioned) would be to deny that there is either cooperation or competition in nature.

Of course it may well be the case that scientists — on both sides — will (rather predictably) respond to this last claim by saying that they’ve stressed neither cooperation nor competition. Alternatively, they may say that they’ve stressed both. Yet, when you read much of the literature, this simply hasn’t been the case!

Indeed Brockman’s The Third Culture is just one among many more graphic examples which display that political bias toward either cooperation or toward competition when it comes to discussions of Darwinism and nature generally.

So nature may not be “red in tooth and claw”, but politicised science most certainly is!

All this stuff about competition vs cooperation (which is clearly political) has also been tied to one other frequent part of this debate — the supposed role of capitalism within Darwinism.

Brian Goodwin certainly tied what he called “Darwinism” to capitalism… and also to much else that’s not (strictly speaking) biological.

Brian Goodwin on Capitalist Science

Just as Darwinism has been linked to capitalism via the former’s stress on competition, so Brian Goodwin also links Darwinism to Calvinism (which, of course, has also been linked to capitalism).

The Canadian mathematician and biologist Brian Goodwin (1931–2009) makes the connection in the following passage:

“There’s a focus on competition in Darwinism because of the notions of progress and struggle. Now we get into theology and how it influences Darwinism, through the Calvinist view that people who have the greater accumulation of goods have proved themselves superior in the race of life. That for me is a whole lot of garbage that can be chucked.”

All that came after the following words:

“There’s too much work in our culture, and there’s too much accumulation of goods. The whole capitalist trip is an awful treadmill that’s extremely destructive.”

Brian Goodwin even connects Richard Dawkins’ Darwinism to what he calls “Christian fundamentalism”. But not in the usual way of saying that “Darwinists are as fundamentalist as Christian fundamentalists”. No, Goodwin also connects Dawkins’ bad Darwinism to fundamentalist Christianity in detailed theological ways which (seemingly at least) have nothing directly to do with fundamentalism. This is Goodwin on Dawkins:

“I suddenly realized that this set of four points was transformation of four very familiar principles in Christian fundamentalism, which go like this; (1) Humanity is born in sin; (2) we have a selfish inheritance; (3) humanity is therefore condemned to a life of conflict and perpetual toil; (4) but there is salvation.

“What Richard has done is to make absolutely clear that Darwinism is a kind of transformation of Christian theology. [] I suspect that Richard was at one stage fairly religious, and that he then underwent a kind of conversion. [].”

Technically, isn’t it the case that points (1), (2), (3) and (4) were vital parts of mainstream — i.e., not “fundamentalist” — Christianity for over 1,500 years? (Unless, that is, Goodwin believed that virtually all Christianity was fundamentalist.) Weren’t those precepts built into almost all Christianity?

In any case, instead of capitalism, Darwinism, Calvinism, fundamentalist Christianity, etc., Goodwin offered this alternative:

“Once you get rid of it, you’re into a different set of metaphors, related to creativity, novelty for its own sake, doing what comes naturally.”

This is very vague stuff. And, of course, if one is that way inclined, then being vague (if also poetic) and following one’s emotions are fine. Nonetheless, why isn’t there any “creativity” built into Darwinism — at least of the kind of Darwinism Goodwin pointed his finger at? And was Goodwin keen on literally all examples of “novelty for its own sake”? Did that include the many types of cancer, creative forms of violence and torture, capitalist creativity and novelty, etc? And, finally, Goodwin must have realised that everything that everyone and everything does “comes naturally” because there’s no other way for it to come.

That said and to repeat: Goodwin believed that all this creativity, novelty and doing what comes naturally (whatever those things could possibly mean) are in opposition to

“the image of organisms struggling up peaks in a fitness landscape, doing ‘better than’ — which is a very Calvinistic work ethic”.

Goodwin, on the other hand, sums up his political vision as a “creative dance”.

Brian Goodwin’s Metaphors

Goodwin said that what he was against was only a “set of metaphors”. Indeed he (more or less) admitted that his own alternative was only a set of metaphors too.

Firstly, the metaphors he politically disliked:

“Instead of the metaphors of conflict, competition, selfish genes, climbing peaks in fitness landscapes, what you get is evolution as a dance. It has no goal. As Stephen Jay Gould says, it has no purpose, no progress, no sense of direction.”

And there are similar metaphors (if about a different subject) in the following passage from Brockman’s book. However, this time these metaphors aren’t from Brian Goodwin himself: they’re from the biologist Francisco Varela:

“Deconstruct the militaristic notion that the immune system is about defense and looking out for invaders. Deconstruct the notion that evolution is about optimizing fitness to live in the conditions present in some kind of niche. [] Deconstructing adaptation means deconstructing neo-Darwinism.”

There are certainly problems with using metaphors. And it’s not just a question of using ideologically incorrect (or ideologically correct) metaphors either. Sometimes metaphors themselves (i.e., whatever political content they may contain) are overused or inherently problematic.

For example, I doubt that Goodwin or Verela would have liked the following metaphors from the inventor and computer scientist W. Daniel Hillis (again, from Brockman’s book):

“Would you please take the 10 percent of those random programs that did the best job, save those, kill the rest, and have the ones that sorted the best reproduce by a process of recombination, analogous to sex. Take two programs and produce children by exchanging their subroutines.”

Despite mentioning metaphors, Brian Goodwin did start off with a critical tract about Calvinism, capitalism and competition in which he doesn’t even mention metaphors — or, indeed, use any metaphors.

What’s more, substituting one set of political metaphors for another set of political metaphors seems to defeat the object. Or, at the very least, we’ve clearly moved way beyond biology and evolutionary science here…

Unless, that is, politics and metaphor are inescapable in this area of science. Indeed some “politically-engaged scientists” have argued precisely that.

Brian Goodwin then moved on to advance his more obviously political vision. Or, at the least, Goodwin demanded that “nature and culture” must merge. And that demand can very easily be interpreted as meaning that nature and politics (i.e., the right kind of politics) must merge. (It can be doubted that Goodwin would have put it that clearly and openly.)

In detail, Goodwin stated:

“This is why indigenous cultures are beginning to be recognised for their values — because they were not accumulating good; they were living in harmony. They were expressing their own natures, as cultures. Nature and culture then come together.”

Firstly, this is a very vague use of the term “indigenous cultures”. It’s rarely clear what people mean by those words. In any case, isn’t it a generalisation to put literally all (well) indigenous cultures in the same basket? (Indeed, if Goodwin’s stereotypes had been negative, then they would have been classed as racist.) The literary critic and political activist Edward Said (1935–2003) picked up on this line of thinking when he argued that positive Orientalism (see here) is just as bad as negative Orientalism.

Indeed this Goodwinian romanticisation of non-Western cultures — which parallels its negative (or openly racist) opposite in both historical lineage and style — dates back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (via people like the cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead — see here). For Rousseau, his positive Orientalism (or his purely positive view of… indigenous cultures) was largely a figment of his own romantic imagination (though his admirers are keen to say that the term “noble savage” was never uttered by Rousseau himself), his dearth of genuine knowledge of any cultures outside Europe (see here), and his hatred of what he saw around him in the West (or simply in France) …

And all that seems very familiar and contemporary.

No comments:

Post a Comment