Some critics (or downplayers) of the philosophy of science (or philosophy generally) may argue that Isaac Newton didn’t actually have a philosophy of science at all. Instead, he simply did what he did. That is, no matter how complex and reasoned Newton’s maths, observations, experiments, etc. were, it was still “just science”.

“Empiricism is the epistemology which has tried to make sense of the role of observation in the certification of scientific knowledge.” — Alex Rosenberg (see source here)

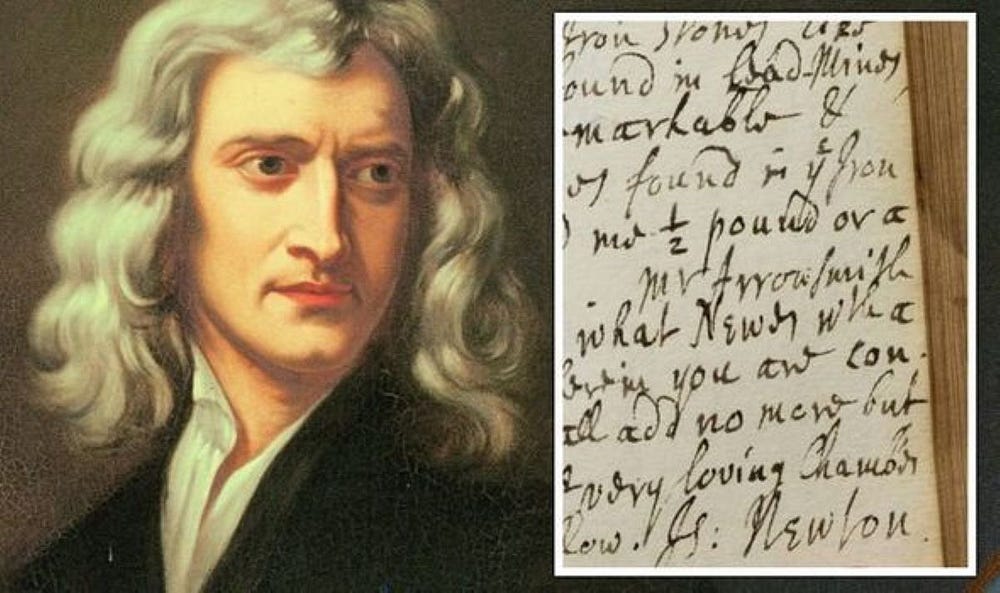

It’s true that Isaac Newton never used the words “philosophy of science” about his own words and work. Indeed, he wasn’t overly self-conscious about the philosophical and methodological underpinnings of his science. But none of this means that Newton didn’t actually have a philosophy of science or that he didn’t uphold philosophical positions (i.e., as they were directly relevant to his work) on the nature of science itself.

In addition, the classification empiricist science may seem like a truism or even a tautology. At least it’s what many laypeople (though not really many scientists) take science to be anyway. That is, science is often deemed to be mainly (or even only) about observations and experiments… Or at least many laypeople believed that it should be!

All that said, it’s now worth saying that these statements have nothing directly to do with the commonplace fact that science was classed as natural philosophy in the 17th century. In addition, it has nothing to do with the general idea that philosophical ideas and theories underpinned much science in those days (as they continue to do so today).

So, then, this essay is purely about Newton’s very own philosophy of science.

It’s also worth noting here (i.e., to set the scene) that David Hume’s more self-conscious and obvious general philosophy is in some ways like Isaac Newton’s philosophy of science. Indeed, often all one really needs to do is substitute Hume’s 18th-century term “impressions” (or “sense impressions”) for Newton’s earlier term “phenomena”. More relevantly, Hume believed that only concepts “derived from” impressions were relevant and significant. One can even read Hume as arguing that sense impressions are the exclusive source of all the knowledge we have of what he called “matters of fact”.

In terms of concrete examples, then, Hume had a problem with such “hypothetical entities'” as substance, vacuum, necessary connection, the self, etc. (All this can be found in Hume’s book An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding.) And, similarly, Newton had a problem with such things as the aether, corpuscles and what he called “occult properties”.

All that said, an empiricist tradition can be said to go all the way back to Aristotle and even before him. After all, the ancient Greek philosopher did believe (or state) that “there is nothing in the intellect which was not first in the senses”.

Phenomena First

Isaac Newton stressed that scientists should observe what he called “phenomena”. (It’s hard to imagine many scientists — or even philosophers — not doing so.)

For example, Newton argued (as did Aristotle before him) that a scientist (or a natural philosopher) should carefully examine the world around him. In Newton’s own words:

“[A]lthough the arguing from Experiments and Observations by Induction be no Demonstration of general Conclusions, yet it is the best way of arguing which the Nature of Things admits of.”

It can be seen that Newton wasn’t a naive (or absolute) empiricist. In other words, he never believed it was literally all about “experiments and observations”. Yet, arguably, very few scientists — or even philosophers — have ever thought that way in any case. In Newton’s own example, then, he did say that he was arguing “from” experiments and observations. That is, he didn’t say that experiments and observations were the beginning and the end of all science. So Newton’s science was certainly no mere (as the phrase has it) “cataloguing of observations” either.

Still, Newton not being an absolute empiricist doesn’t mean that he wasn’t an empiricist at all.

Technically, Newton’s “conclusions” came from his experiments and observations. Thus, his conclusions weren’t merely (or exclusively) statements about the his actual experiments and observations. This also meant that any moves from experiments and observations to conclusions weren’t determinate or necessary. And that also had the consequence that Newton’s own experiments and observations (indeed all experiments and observations) could have led to different conclusions. Indeed, Newton was well aware of that.

Induction and Deduction

Newton believed that scientific processes must be kept in check in two ways:

(1) Inductive evidence must provide the groundwork of scientific work.

(2) The consequences derived from inductive evidence must themselves be experimentally confirmed.

Of course, Newton’s use of the word “induction” needs to be fleshed out a little.

Arguably, there’s no such thing as a purely inductive process. And that’s even before any general “conclusions” are formulated.

Yet all this entirely depends on what Newton — as well as others — meant by the word “induction” in the 17th century.

More specifically, it’s a little difficult to know (or simply accept) what Newton meant by the phrase “arguing from Experiments and Observations by Induction”. That’s primarily because even during any inductive process there’ll still be other processes being employed. In addition, there’ll be theories, biases, prior knowledge, etc. which explain why those particular experiments were carried out in the first place. What’s more, it can be asked why Newton (or anyone else) observed those particular phenomena. Here again, theories, biases, preferences, scientific (as well as other) traditions, etc. must have been lurking in the background all along.

Of course, Newton did note that science involved both induction and deduction (i.e., not only one at the exclusion of the other). He did, after all, stress the drawing out of what he called “consequences”. Yet, here again, this almost seems obvious. Indeed, this stress on both induction and deduction can previously be found in the work of Roger Bacon, Robert Grosseteste, and, later, in the work of Galileo and Francis Bacon.

All that said, Newton certain did (as it were) come down on the side of induction (i.e., as against deduction).

For example, Newton once wrote that “particular propositions are inferred from the phenomena, and afterwards rendered general by induction”. This Newtonian and inductive methodology was applied to the following real cases. In Newton’s own words:

“Thus it was that the impenetrability, the mobility, and the impulsive forces of bodies, and the laws of motion and of gravitation, were discovered.”

But, here again, one can ask: Why these phenomena?

In this case, then, was Newton looking for the properties of impenetrability and impulsive force? And why did he assume any “laws” at all?

So it can even be argued that Newton’s own (as it were) grounding phenomena were already drenched in both theory and philosophy (or metaphysics) from the very beginning.

What’s more, even if Newton’s phenomena were pure, he still never discussed (let alone argued for) that transition from phenomena to the laws of motion or the laws of gravitation. As Rationalists may put it (to use a line of argument found in Laurence BonJour -see here), the phenomena may be as pure and empirical as you like. However, how did Newton (or anyone else) explain the links from the phenomena to any general laws or conclusions? After all, these links aren’t themselves phenomena and neither are they (i.e., in themselves) examples of induction. (This is the case even if the whole process itself can be deemed to be inductive in nature.)

Hypotheses Non Fingo

To put it simply: Newton believed that “theories” were acceptable, and that “hypotheses” were (largely) unacceptable. Of course, Newton used these terms in his very own (17th-century) way.

Yet, predictably, Newton broke his own rules on this strong distinction between theories and hypothesises (as we shall now see).

Newton’s term “theory” is used for that which can be “deduced from” what is observed and/or experimentally produced (or noted). Thus, inductive evidence can lead to a theory about such evidence. This Newtonian account of a scientific theory isn’t really a million miles from how the term is used today by educated laypersons and even by some scientists. However, Newton’s use of the word “hypothesis” is very odd to 21st-century ears.

For example, Newton once claim that hypotheses were (in relevant cases) about what he called “occult qualities”. And what are occult properties? In basic terms, they’re properties which can’t be observed or “measured”. (It’s odd, then, that some modern day — well — “occultists”, “spiritualists”, etc. often state “That’s just a theory!” to those scientists they disagree with.)

Thus, Newton didn’t like his own theories being classed as hypotheses.

A good example of Newton’s inductivist and/or empiricist inclinations (i.e., as they relate to this theory-hypothesis distinction) was his aversion to (using Stephen Toulmin’s phrase) “going beyond the phenomena”.

Take Newton’s theory of light.

Newton distinguished what can be observed from what may (or may not) underlie what it is scientists observe. In this case, then, scientists can observe certain properties of refraction. Thus, they can form a theory about such properties because they can observe them. However, they can’t observe what may (or may not) underlie such properties. In Newton’s case, then, scientists couldn’t observe (invisible) “waves” or “corpuscles”.

Now take the important — and similar — case of gravitational attraction.

Newton didn’t (or simply claimed not to) hypothesise about the underlying causes of gravitational attraction. Indeed, Newton famously stated the following three words: Hypotheses non fingo (“I frame no hypotheses”). Instead, and at least according to his own self-image, Newton simply noted phenomena and (as it were) observed what they did. And clearly — in this case at least — Newton couldn’t observe the underlying causes of gravitational attraction. (Some contemporary analytic philosophers may say that Newton couldn’t observe what they call “intrinsic properties”.)

The French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650), on the other hand, did believe that he could hypothesise (or even know) about such underlying causes! He believed that gravitational attraction could be (or is) explained by vortices of aether.

Yet, despite all that, Newton did indeed hypothesise.

For example, Newton accepted that the aforementioned corpuscles and the aether may well exist. However, he still noted that scientists simply couldn’t observe such things. Thus, at best, Newton concluded that what came to be called “hypothetical entities” (or “theoretical entities”) may indeed be of some use in scientific research. However, scientists should never play fast and loose with such entities.

My flickr account.

No comments:

Post a Comment