The English philosopher Philip Goff has used the words “consciousness is a datum in its own right” a few times in his writings and interviews. Other philosophers have expressed exactly the same idea (if in different words).

The Latin word datum can be translated as “(thing) given” and “to give”. Thus, a datum has been deemed to be something that is (as it were) theory-free (i.e., something that’s given before it’s theorised about). Of course, this isn’t to say that all (or even most) scientists and philosophers take the word “datum” in that limited and etymologically-strict way. That said, some scientists and philosophers certainly have taken this word to mean that-which-is-given.

Is this the case with Philip Goff?

Now how does Goff’s own datum that is consciousness stand within the context of all the books and papers which he and others have read on the subject of consciousness? What’s more, can any distinction at all be made between such a datum and all the things each philosopher and layperson has read about it?

In other words, if readers have read lots of (or just some) books on consciousness (or, alternatively, come across the word “qualia” many times), then surely that will impact on how they describe and/or theorise about any ostensibly (to use Goff’s words again) “private seemings” they may have.

Now take specifically those who stress how things seem to them.

Don’t they (or a least some of them) additionally take these seemings to be the basis for what they also take to be qualia? Relevantly, most of these people would deem it ridiculous to say that technical terms, definitions, theories, books on consciousness, etc. have anything to do with qualia or how things seem to them…

However, these things most certainly do have a lot to do with the matter of consciousness — and even a lot to do with subjects’ phenomenological descriptions of their subjective states and qualia.

So it’s not really private seemings which are the problem: it’s what people say about them. More relevantly, it’s how people philosophise and theorise about them. Indeed, it’s also about how reading books about consciousness (or coming across the word “qualia” all the time) may influence what they say about consciousness.

More strongly, perhaps when a layperson first uses the word “qualia”, then that’s precisely the moment he/she stops being a layperson. (Of course, such a person doesn’t also need to be an expert, or to have read lots of academic papers on qualia.) Indeed, the philosopher Patricia Churchland once said that the word “‘qualia’ is a term of art, which was introduced by philosophers”.

So it’s relevant to bring up the historical phenomenologists here.

According to the German philosopher Rüdiger Safranski, the “great ambition” of Edmund Husserl and “his followers” was to

“disregard anything that had until then been thought or said about consciousness or the world [while] on the lookout for a new way of letting the things [they investigated] approach them, without covering them up with what they already knew”.

As already argued, most laypersons don’t believe they’re covering anything up when they discuss their subjective states — or at least when they discuss their qualia. (They believe that qualia are theory-free.) Husserlian phenomenologists, on the other hand, realised that consciousness came with baggage, and that was precisely why they wanted to get beyond that baggage.

So an important (or at least relevant) question here is the following:

Could we see our own subjective states, or even our own qualia, in any other way?

The Canadian philosopher Paul Churchland (to take just one example) believes that we could.

Churchland goes into detail in the following passage:

“Given a deep and practiced familiarity with the developing idioms of cognitive neurobiology, we might learn to discriminate by introspection the coding vectors in our internal axonal pathways, the activation patterns across salient neural populations, and myriad other things besides.”

Of course, at present it would be virtually impossible (even in the case of all neuroscientists working collectively together) to describe our (to use Churchland’s own words) “first-person” thoughts, feelings and beliefs in terms of “coding vectors in our internal axonal pathways”, “activation patters across salient neural populations”, etc. Indeed, it may be hard to even imagine such a state of affairs at present.

However, Churchland wasn’t talking about the case as it is today. He explicitly stated that

“it is entirely possible for a person or culture to learn and use some other framework in that role”.

Clearly, this is a statement about the future. In other words, this isn’t about an elite group of neuroscientists imposing a new language on the populace today — or even slowly over the years.

On the other hand, if the “language” of folk psychology has been with us since human language itself began (or perhaps even before), then perhaps Churchland’s wishes for the future may be a little utopian. (Or, depending on one’s views, dystopian.) After all, there’s surely a difference between people or cultures picking up new words or terms (which happens all the time), and people picking up a new language to talk about their subjective states. However, surely critics can’t argue that this is something that won’t — or can’t — happen in the future.

Incidentally, Churchland isn’t an eliminativist about qualia. [See his ‘Knowing Qualia : A Reply to Jackson’.] Although Churchland wants to eliminate (which isn’t a very helpful word) propositional attitudes (see here), he doesn’t actually want to eliminate qualia. Instead (as already stated), Churchland simply wants to re-envision what qualia (as well as other mental states) are, and how we should theorise (or philosophise) about them.

Against Phenomenology?

The position advanced in this essay is at least partially in agreement with one that the American philosopher Owen Flanagan advanced in the following passage:

“One might nonetheless think [i.e., after reading the arguments in favour of phenomenology] that phenomenology does more harm than good when it comes to developing a proper theory of consciousness, since it fosters certain illusions about the nature of consciousness.”

Indeed, Flanagan also told us that

“[s]ome philosophers think that phenomenology is fundamentally irrelevant”.

Flanagan then told us why that’s the case:

“Firstly, there is no necessary connection between how things seem and how they are. Second, we are often mistaken in our self-reporting, including in our reporting about how things seem.”

It’s a fact that things seem a certain way (in terms of mental states) to certain human subjects at certain times — or even to all subjects at all times!

Not many philosophers or scientists would deny that.

However, isn’t there often a conflation (or confusion) here between seeming and what actually is the case? (Sure, this is an epistemological minefield, which has been frequently discussed.)

For a start, even a hardcore phenomenologist (or “qualiaphile”) can’t treat all subjective accounts as gospel because such accounts often contradict each other. However, things still seem a certain way even if those seemings are given contradictory descriptions or accounts. In other words, in all these cases, there was still a way that things seemed.

But who’s denying that?

What’s more, what work does this acknowledgement of seemings do for the science and ontology of consciousness?

Again, there is indeed a “how things seem”. However, how should we theorise/philosophise about how things seem? How should we scientifically scrutinise such seemings? Clearly, we can’t believe that if things seem a particular way, then they must be that particular way.

This is a lesson many students of philosophy learned in their first philosophy class.

It detail.

To subject S, the cricket bat in the water seems to be bent. Yet that doesn’t mean that the cricket bat is bent — it’s refracted. Similarly, subject S hallucinating a red goblin is “private to the person” who has that hallucination. However, we wouldn’t conclude that the red goblin actually exists.

Yet aren’t many people doing something similar to that when it comes to their own seemings? Or does all this mean that we can’t make mistakes about private conscious (or mental) states? Yes we can. Indeed, there’s a large literature on this very subject which tells us that we often do. [See here.]

So why should the case be in different when it comes to phenomenology or the reports of our own subjective states?

It is because they’re “purely internal”?

Does that really make a difference?

Well, there may well be a difference between looking at a stick in the water and reporting on one’s own mental state. However, do many people assume that no mistakes can be made about the latter, but they can be made about the former?

Isn’t this an implicit adoption of the idea of Cartesian infallibility about subjects’ mental states?

To return to the opening theme:

How do Philip Goff’s words “consciousness is a datum in its own right” fit into all this?

In other words, how does the datum of consciousness fit into the phenomenological descriptions (or simply the “verbal reports”) of such a thing?

Take the arguments of Owen Flanagan again.

Owen Flanagan on Phenomenology

Strictly speaking, Owen Flanagan’s use of the word “phenomenology” doesn’t square too well with many other accounts of phenomenology (i.e., as mainly found in — to generalise - continental philosophy).

Flanagan’s usage, instead, is more in tune with the etymology of the word, as in this account:

“The term phenomenology derives from the Greek φαινόμενον, phainómenon (‘that which appears’) and λόγος, lógos (‘study’).”

The relevant words in the above are “that which appears”. Indeed, the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl once used the (Cartesian) words “given in direct ‘self-evidence’” when he referred to what he was doing

Flanagan’s usage, on the other hand, doesn’t strictly abide by the following definition:

“Phenomenology is the philosophical study of objectivity and reality (more generally) as subjectively lived and experienced.”

In simple terms. Flanagan’s use of the word “phenomenology” seems to factor out (or simply ignore) “objectivity and reality”. More correctly, Flanagan believes that the qualiaphiles and anti-physicalists he’s arguing against do so.

So although Flanagan (as it were) accepts phenomenology, he’s also a naturalist whose writings are full of scientific detail and case studies. This means that he’s certainly not a phenomenologist in the following sense either:

“Phenomenology proceeds systematically, but it does not attempt to study consciousness from the perspective of clinical psychology or neurology. Instead, it seeks to determine the essential properties and structures of experience.”

As already stated, Flanagan’s position is at odds with what many other philosophers (though not all) have taken phenomenology to be. That said, it’s not being said here that Flannagan actually claims to be a phenomenologist (at least not in any strict sense). Instead, his position is that phenomenology is something that naturalists (such as himself) should accept, take note of, and tackle.

In basic terms, Flanagan believes that phenomenology (to ironically rewrite Goff’s opening slogan) is a datum in its own right.

In any case, Flanagan actually bounces off both Daniel Dennett and Dennett’s opponents, as will now be shown.

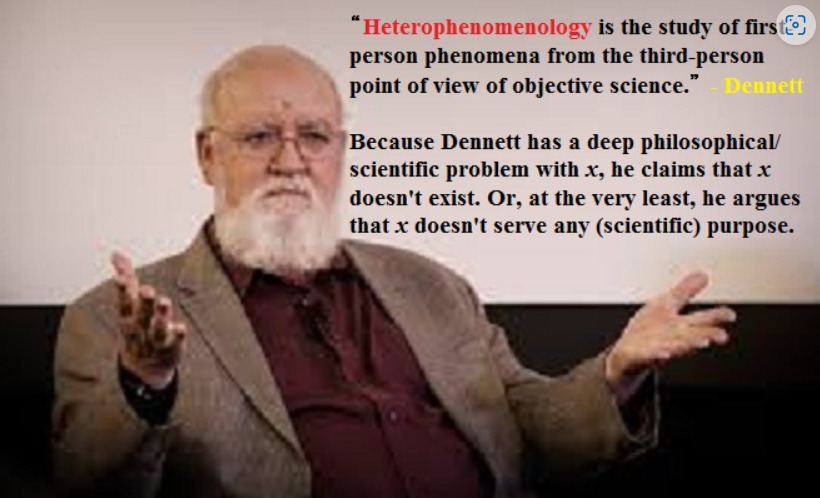

Daniel Dennett’s Heterophenomenology

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett has created his own neologism: “heterophenomenology”. Heterophenomenology is the

“study of first-person phenomena from the third-person point of view of objective science”.

Since phenomenology was originally seen as a (to use Dennett’s own words) “catalogue of phenomena”, then there’s no necessary reason why it should only be a study of subjects’ accounts of their own first-person mental states.

Dennett goes into more detail when he adds that heterophenomenology

“exploits our capacity to perform and interpret speech acts, yielding a catalogue of what the subject believes to be true about his or her conscious experience”.

Again, this isn’t a “catalogue” of conscious experiences, pains, mental states, qualia, etc. (as it were) in themselves. It’s a catalogue of the “speech acts”, etc. about these things. In other words, physiological responses, physical behaviour, “verbal reports”, etc. are the (as it were) meat of heterophenomenology — not consciousness, experiences or mental phenomena in themselves…

Of course, Dennett would argue that there can’t even be anything in itself in these cases.

Since phenomenology was originally seen to be the study of phenomena (again, according to Dennett) “before there is a good theory of them”, then how does this work in the case of third-person (scientific) accounts of first-person mental phenomena? After all, Husserl and other phenomenologists saw their own phenomenology as being “presuppositionless” and “non-theoretical”. Not only that: (for Husserl at least) it was an attempt to provide a basis (or grounding) for science. [Husserl’s purpose was substantially Cartesian in nature. See here.]

Now can it also be said that Dennett’s own brand of phenomenology (if that’s what it actually is) is presuppositionless, non-theoretical, and a basis for (i.e., rather than a part of) science?

Of course it can’t!

So, yes, it’s indeed the case that studying any kind of phenomena can be deemed to be phenomenology. (This is true by definition.) However, studying mental phenomena as a project in science (i.e., with its own presuppositions and theories which will be applied to such phenomena) surely can’t be classed as phenomenology — at least not in the way that historical phenomenologists saw things.

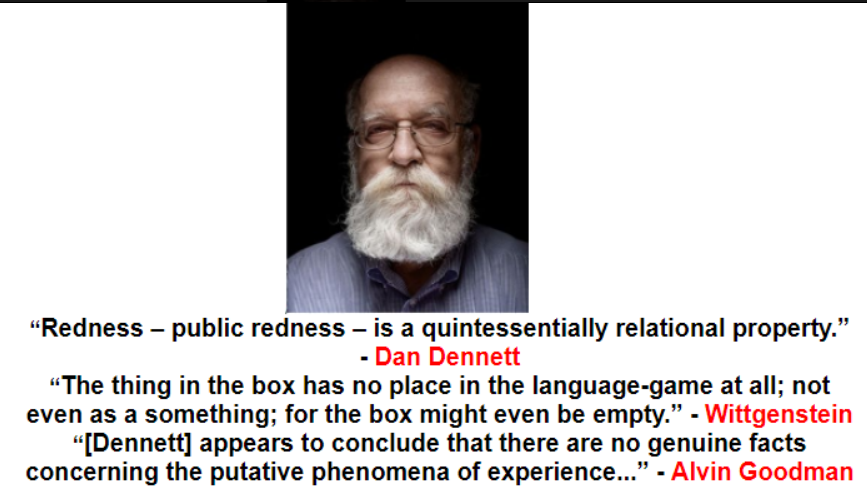

Dennett on Qualia (Via Flanagan)

Even Daniel Dennett himself accepts that qualia are “real”… at least according to Owen Flanagan. In detail, Flanagan wrote the following:

“Qualia are for real. Dennett himself says what they are before he starts quining. Sanely, he writes, ‘‘Qualia’ is an unfamiliar terms for something that could not be more familiar to each of us: the ways thing seem to us’ [].”

Okay — there are ways things seem to us.

But where do we go from there?

Dennett may well (initially) accept qualia. However, he certainly doesn’t accept what he takes to the main philosophical account of them to be. [See here.] In other words, such qualia (at least in Dennett’s view) are mere “quicksilver” (i.e., “things” with very little scientific or even philosophical point).

In detail. Flanagan (again) puts Dennett’s position on qualia in the following way:

“To think this, Dennett must think that the identification of qualia with the ‘way things seem to us’ must be interpreted as meaning that a quale is a state such that, necessarily, being in it seems a certain way and, necessarily, there is nothing else to it.”

On this account of Dennett (if in crude terms), if quale x (or set of qualia y) “seems a certain way”, then it seems a certain way…

There is nothing else to it.

So perhaps Dennett’s account of qualia (if via Flanagan) is made of straw.

That said, if Dennett’s account weren’t broadly accurate, then qualia wouldn’t do all the work their supposed to do for anti-physicalists and many others. In other words, such people actually require Dennett’s account of qualia to be accepted. That’s because without it their own case against physicalism, etc. simply won’t work. [Note: some physicalists accept the existence of qualia.]

So it’s not just the case that Dennett wants to portray qualia in this (seemingly?) extreme way: it seems that qualia enthusiasts do so too. That’s because (again) if qualia aren’t taken to be as Dennett believes they’re taken to be (i.e., by qualiaphiles), then what would be the (philosophical) point of them?

More broadly, much qualia-talk is (as it were) designed to end up with Flanagan’s final statement — “there is nothing else to it”. That nothing else to it is used to guarantee qualia complete freedom and autonomy from any (complete?) physical account or description of them.

As it is, Flanagan is unhappy with Dennett’s account.

Flanagan on Dennett’s Position

Flanagan wrote:

“[] I claim that the concept simply doesn’t need to be understood that way. The alternative interpretation is that a quale is a state such that being in it seems a certain way. This interpretation is better because it allows us the concept of the way things seem without making seemings atomic, intrinsic, exhaustive, ineffable, and so on.”

This is a hard passage to grasp. (I needed to read it more than once.)

On first reading, Flanagan seemed to be simply repeating Dennett’s own account of qualia — if with slightly different wording.

Thus, in one passage Flanagan says that Dennett identifies qualia “with the ‘way things seem to us’”. On Flanagan’s own account, on the other hand, “a quale is a state such that being in it seems a certain way”.

So is there a substantive difference between the way x seems to us, and quale x is a state such that being in it seems a certain way? (Other than Flanagan’s use of the words “a quale is a state”.)

That question just asked, I believe that Flanagan’s point is the following.

For both qualiaphiles and for Dennett, quale x seeming a certain way is (literally) the end of the story. To Flanagan, on the other hand, being in state x, and quale x seeming a certain way to us, isn’t the end of the story.

On this reading, then, we have an explanation as to why Flanagan concluded with the following words:

“This interpretation is better because it allows us the concept of the way things seem without making seemings atomic, intrinsic, exhaustive, ineffable, and so on.”

Thus, Flanagan’s interpretation is better (to Flanagan at least) because even though there are indeed (as it were) brute seemings — that’s not the end of the story…

However, surely it isn’t (or wasn’t) the end of the story for Dennett either.

So perhaps Flanagan’s point is that we can accept that there is a way things seem, yet not also take these seemings to be (Flanagan quotes Dennett’s terms) “atomic, intrinsic, exhaustive, ineffable, and so on”.

Flanagan’s conclusion (if I have it right) can be summed up in this way:

(i) Because Dennett believes that qualia must be construed as being “atomic”, “intrinsic”, “exhaustive” and “ineffable”,

(ii) then, to qualiaphiles, that must be the end of the story.

This means that Dennett is taking the qualiaphiles and anti-physicalists at their word.

Flanagan, on the other hand, isn’t taken them at their word.

Instead, Flanagan’s “alternative interpretation” is that “a quale is a state such that being in it seems a certain way”. (I still don’t really understand this phrasing.) Thus, that isn’t the end of the the story for Flanagan. Indeed, Flanagan supplies lots of very persuasive and interesting philosophical and scientific detail as to why seemings aren’t — or even can’t be — the end of the story.

All the above ties up directly to the broad philosophical position of physicalism and its relation to consciousness (i.e., not just on whether one takes a physicalist or anti-physicalist take on qualia).

Conclusion: Physicalism, Anti-Physicalism or Something Else?

Perhaps the seemingly(?) non-physical nature of mental seemings is largely — or even entirely — down to people’s subjective (or first-person) takes on them. In other words, to the (as it were) “owners”, qualia and/or seemings do indeed seem to be non-physical. Yet do things seeming-to-be-non-physical mean that they are non-physical?

In other words, perhaps there’s a fundamental reason as to why the owner (or haver) of seeming S takes it to be non-physical.

This means that because (to quote Peter Carruthers) “[c]onscious states are private to the person who has them”, then the notion of the non-physicality of seemings will be private to the person who has them too. Yet how can we draw out the actual non-physicality of seemings from such personal “reports” on them?

Indeed, perhaps that seeming-to-be-non-physical-to-subjects is largely a product of personal psychology, learning, books, culture, history, and sociology.

More broadly, what relevance or status do personal (or private) accounts of mental seemings have on the actual metaphysical and scientific status of such things?

No comments:

Post a Comment