[The word “things” is used to refer to objects, entities, particulars, individuals, etc.]

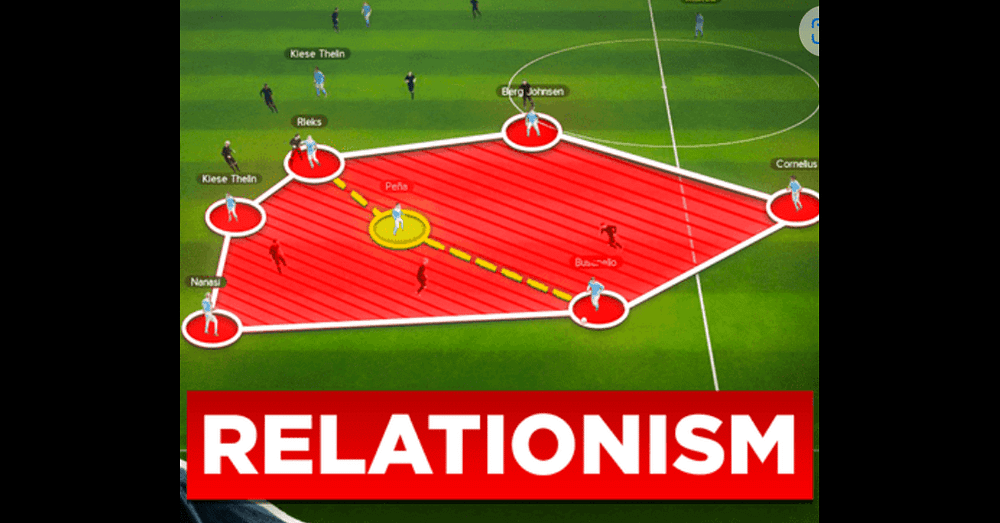

“Relationism” and “relationalism” are terms which denote two different philosophical positions. The following is one account of both terms:

“For relationalism, things exist and function only as relational entities. Relationalism may be contrasted with relationism, which tends to emphasize relations per se.”

Relationism is said to simply emphasise the relations between things: it doesn’t deny that things exist.

With relationalism (i.e., with an added “al”), on the other hand, “things exist and function only as relational entities”. In other words, if there were no relations, then there would be no things.

However, on analysis, the distinctions between these two isms appear to break down — at least in certain respects.

Relationalism is like ontic structural realism in that the latter eliminates things (as in “every thing must go”). Relationism, on the other hand, simply places relations in an important position in any metaphysics.

Having said all that, it’s hard not to see the importance of relations — even if one also accepts the existence of things. (One can also see the vital importance of relations when it comes to — particularly — physics.) Yet, on the other hand, one can’t really see how things could be entirely eliminated. (This may largely depend on how the word “thing” is defined.)

In addition, relationalism itself can be read as not actually being eliminativist (i.e., about things) at all. After all, this metaphysical position may simply have it that things aren’t what’s called “self-standing”, which isn’t in itself a denial that things exist. Alternatively, we can say that literally all a thing’s properties are relational. In other words, things don’t have intrinsic properties. Thus, in a weak (or even strong) sense, if all things only have relational properties (and such properties literally constitute things), then in one sense things are are indeed eliminated from this metaphysical picture. To put that more simply: if a thing’s relations (or relational properties) were eliminated, then it would no longer be that thing. Indeed, it would no longer even exist!

Despite all the above, it’s still hard to make sense of the idea that, to use Lee Smolin’s words, “the world is made of relations”.

What does that mean?

The same goes for Smolin’s claim that “all properties are about relations between things”.

In any case, Smolin explicitly states his relationist (or Leibnizian) position in the following passage:

“There is no meaning to space that is independent of the relationships among real things of the world. [] Space is nothing apart from the things that exist. [] If we take out all the words we are not left with an empty sentence, we are left with nothing.”

However, there may be a problem here (again) with the use (above) of the word “relationist”.

On my own reading, Smolin seems to go one step beyond relationism in order to delve into the domain of relation[al]ism. What I mean by this is that — to repeat — it can be said that relationism simply emphasises the relations between things: it doesn’t deny that things exist. With relationalism (with an added “al”), on the other hand, “things exist and function only as relational entities”. In other words, if there were no relations, then there would be no things.

The arguments above can be used against ontic structural realism, which is very much like relationalism (at least in these respects).

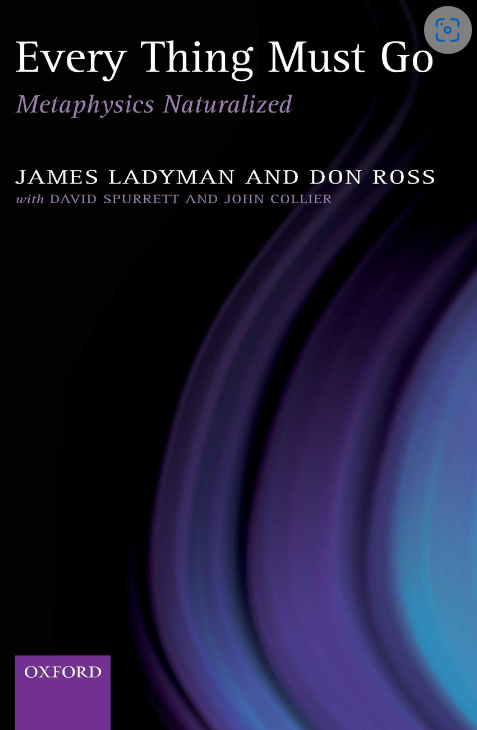

Ontic Structural Realism

James Ladyman and Don Ross offer a list of four statements which they believe summarise the position of what they call “standard metaphysics”.

“There are individuals in spacetime whose existence is independent of each other. Facts about the identity and diversity of these individuals are determined independently of their relations to each other.”

The problem is how to take the word “independent” in the above.

One can happily accept individuals (which is a similar term to particulars), and also believe they that they aren’t independent of other individuals. In other words, the reality of individuated objects, and their lack of independence, aren’t mutually exclusive.

What’s more, one can accept the “identity and diversity of these individuals”, and also deny that such individuals are “determined independently of their relations to each other”. In other words, why is a commitment to individuals necessarily also a commitment to their complete independence from all other individuals (or from relations, events, processes, etc.)?… Unless this is true by definition.

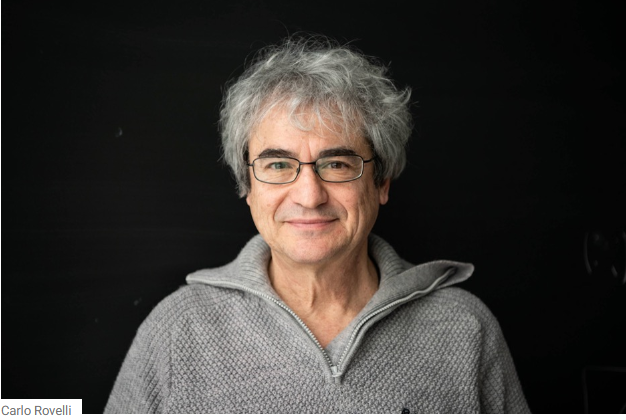

Rovelli’s Binary Opposition: Relations vs Things

This seeming (to use a term from Ferdinand de Saussure) binary opposition between relations and things is given a scientific and historical reading by Carlo Rovelli in the following:

“But physics has long been asked to provide a firm basis on which to place relations: a basic reality underlying and supporting the relational world. Classical physics, with its idea of matter that moves in space, characterized by primary qualities (shape) that come before secondary ones (colour), seemed to be able to play this role [].”

The very phraseology in the above seems odd.

Surely no physicist or scientist would ever have thought in terms of a “relational world” at all. So perhaps that’s precisely Rovelli’s point. In other words, there is indeed a relational word, but physicists simply haven’t seen it that way. Yet if physicists haven’t seen the world this way, then why were they (according to Rovelli) “asked to provide a firm basis on which to place relations”?

The odd thing is that a philosopher, scientist or layperson could accept most of what Rovelli argues, and still believe that things are important — or even vital.

So is Rovelli simply inverting what he sees as the violent hierarchy in which a supreme importance was supposedly given to things in Western philosophy and physics? In other words, is Rovelli now simply putting interactions and relations in the place of things? In addition, if he is doing so, then why is this clear and blatant reversal of a previous hierarchy a better philosophical position?

Lee Smolin’s Relationism/Relationalism

Lee Smolin (who was mentioned a moment ago) cites Gottfried Leibniz as a relationist. Or, at the very least, he sees Leibniz as being a relationist when it comes to space and time. So, unlike Newton, Leibniz

“wanted to understand [space and time] as arising only as aspects of the relations among things”.

Smolin sums up the two opposing positions when he says that “this fight” is

“between those who want the world to be made out of absolute entities and those who want it to be made out of relations”.

Smolin adds that this opposition is a “key theme in the story of the development of modern physics”. [See note 1 on Smolin’s philosophy of space and time.]

In terms of Leibniz again. Leibniz’s position (as expressed by Smolin) is that space and time don’t exist — at least not as independent phenomena. Instead, space and time essentially arise as ways of making sense of the (as Smolin puts it) “relations among things”. In other words, space and time are the means by which we plot the relations between things. That basically means that if there were no things, then there would be no space and time either. That is, space and time aren’t (to use Smolin’s word again) “absolute”: they’re a consequence of things and their interrelationships.

Nonetheless, if space and time don’t exist, then what are these things moving about in?

It can be supposed, of course, that both space and time come into being as soon as there are things which have relations with one another…

But how does that work?

Even if space and time do spring into existence as soon as things spring into existence, then it’s still the case that things move about in space, and exist through time.

So here are two alternative conclusions:

i) Space and time depend on things and their relations.

ii) Things and their relations depend on space and time.

The obvious way out of this opposition is simply to say that there’s no hierarchy involved here: spacetime and things depend on each other. That is, space and time aren’t more important (or fundamental) than things, and things aren’t more important (or fundamental) than space and time.

What’s called “relational theory”, however, is indeed eliminativist about space. This theory has it that if there were no things, then there would be no space either. Relational theory is eliminativist about time too in that if there were no events (in space), then there would be no time.

Note:

It’s hard to decide if Lee Smolin’s position on space and time is a purely metaphysical position, a position within physics and cosmology, or a metaphysical position on the physics and cosmology. Whichever option is taken will make a big difference to how readers should (or will) interpret his positions on this particular subject.

For example, an entirely metaphysical position on space and time may run entirely free of how they’re tackled in physics and cosmology. (You wouldn’t expect this to be true of a physicist like Smolin himself.) Of course, there may also be a degree of interplay between the metaphysics and the physics and cosmology. However, this isn’t always the case.

No comments:

Post a Comment