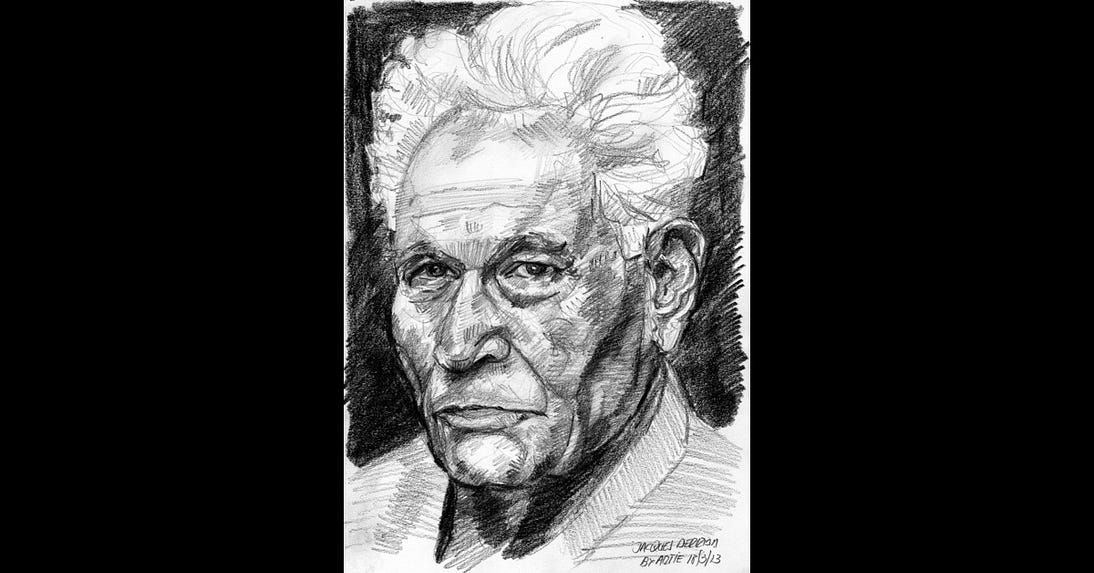

This essay is almost entirely based on a single subsection of a chapter of Jacques Derrida’s book Of Grammatology (1967). In that subsection, Derrida sets up much of the technical groundwork which he required for the destruction (not “deconstruction”) of Western metaphysics. This was the “great epoch” which Derrida challenged. (Within it, we also had “the narrower epoch of Christian creationism and infinitism”.)

“The destruction of the book [ ] is now underway in all domains. [And] violence [against the book] is necessary.”

— The passage above is from the last paragraph of the subsection ‘The Program’ of the chapter ‘The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing’, which can be found in Derrida’s book Of Grammatology.

Derrida vs Western Metaphysics

It must immediately be said that Jacques Derrida made much of the fact that he never claimed to have escaped (or transcended) Western metaphysics. Indeed, he believed this to be impossible. Or, using his own words, the metaphysical notions discussed below were deemed to be “necessary and, at least at present, nothing is conceivable for us without them”.

So Derrida’s deconstruction of Western metaphysics didn’t mean that he had somehow escaped it. Instead, he claimed to have

“demonstrat[ed] the systematic and historical solidarity of the concepts and gestures of thought that one often believes can be independently separated”.

Derrida deemed Western metaphysics to be a system (i.e., much as languages — however broadly construed - can be deemed to be systems). That’s why Derrida argued that once we bring in a single metaphysical concept into the discussion, then we’ve automatically brought in “the entire syntax and system of Western metaphysics”.

So did Derrida create a system in order to deconstruct another system (i.e., Western metaphysics)? Did he also require a metanarrative in order to “question” this bigger system (which included all previous metanarratives)?

As already hinted at, there’s no doubt that Derrida’s aim was (as it’s often put) radical. Indeed, he even out-radicalised

“the tradition [that] professed to withdraw meaning, truth, presence, being, etc., from the movement of signification”.

(According to Derrida, this was “the tradition” that “treat[ed] as suspect, as I just have, the difference between signified and signifier”.)

Derrida was more radical, according to himself at least, because he carried out his own deconstruction/s not in order to offer his own “present truth, anterior, exterior or superior to the sign, or in terms of the place of the effaced difference”, but to question even the deconstruction itself.

This can be interpreted as Derrida’s one-upmanship against philosophers who were already radical.

In detail. According to Derrida, such philosophers didn’t believe that “meaning, truth” etc. belonged to “signification” (written words, etc.). However, they did reject “the difference between signified and signifier” in that the signified was already deemed to be polluted by the signifier. Yet, according to Derrida, such philosophers were still playing the same old metaphysical game. That is, they were still offering their own “present truth” in place of the old truth. To Derrida, the present truth needed to be questioned too. Indeed, it’s because of this that

“the work of deconstruction, its ‘style,’ remain by nature exposed to misunderstanding and nonrecognition”.

One philosophical consequence of these positions (i.e., of both the old questioners and Derrida himself) is that deconstruction itself is bound to be misunderstood and misrecognised.

So isn’t it odd that Derrida himself got so hot under the collar about the “misinterpretations” of his own work (as well as of deconstruction generally)? According to the logic of his own philosophy, there is no meaning, truth, understanding, recognition, etc. to be had when it comes to deconstruction…

Yes, you cannot get Derrida right!

Speech (or the Voice)

At first glance, it’s hard to understand why Derrida saw the text/book, signifier/signified, writing/speech, etc. distinctions to be so important.

So why was speech (or “the voice”) deemed to be so important to those philosophers whom Derrida targeted?

Speech was important because it was deemed to be closer to “meaning” (or it best captures meaning). However, there have been many ways to bring this closeness about.

Derrida singled out the case of Aristotle. He quoted Aristotle thus:

“‘[S]poken words (ta en tê phone) are the symbols of mental experience (pathemata tes psyches) and written words are the symbols of spoken words.’”

So, in this case at least, mental experience is even closer to the logos (or to meaning) than “spoken words”. Of course, in many cases mental experience needs to be expressed. Thus, we have spoken words.

Now we have a three-way relation: mental experience/spoken words/written words.

Derrida particularly wanted to break the binary opposition between spoken words and written words (i.e., without giving too much attention to Aristotle’s mental experience).

According to Derrida, “the voice” was the “first signifier”. It was believed to have a “essential and immediate proximity with the mind” (or the earlier mental experience).

But we can go further.

The voice “mirror[s] things by natural resemblance”. Thus, here we meet, at least in one form, Richard Rorty’s “mirror of nature”. (Rorty’s book Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature was published some 12 years after Derrida’s Of Grammatology.) That said, the voice wasn’t believed to mirror nature, but to mirror the “unclouded mind”, and thereby the logos. Of course, this may turn out to be two different ways of saying the same thing.

It was one step from all the above for Derrida to coin the term “phonocentrism”.

Writing and the Spoken Word

A major theme in Derrida’s early work is that writing was always (to use a common English phrase) looked down upon. It was seen to be inferior to the spoken word. Or, to use Derrida’s technical prose, writing was deemed to be a “secondary and instrumental function”. In simple terms, writing was a “translator of a full speech”.

Why was full speech deemed to be superior?

Full speech was deemed to be “fully present”. In more detail, it was deemed to “present to itself, to its signified”. More importantly, the spoken word, unlike the written word, is “shielded from interpretation”.

It must be noted here that the technical term “writing” is applied across the board. According to Derrida, it includes “cinematography, choreography, of course, but also pictorial, musical, sculptural” works. Indeed, “[o]ne might also speak of athletic writing, and with even greater certainty of military or political writing”.

Derrida didn’t go into detail on this (at least not in the chapter focussed on in this essay), but readers can conclude that these are examples of writing because writing (somehow) infects all of them. In simple non-Derridean terms, cinematography, choreography, pictures, music and sculptural works must be infected because it’s hard to imagine how they could so much as exist without prior (in non-Derridean terms) speech and words. Choreography, for example, requires spoken/written instructions, spoken/written details, stories, etc. And those instructions, details, stories, etc. can’t uphold the superiority of (in Derrida’s terms again) speech. (Everything just said is more obviously true of “political writing”.)

Derrida bounced off two philosophers in respect to the above: Plato and Rousseau. They did much to set up the particular binary opposition of speech and writing. Of course, it can be found elsewhere too, and Derrida mentions “the Rationalists of the seventeenth century”… In fact, the entire history of Western metaphysics is guilty of “binary thinking”.

In terms of Rousseau (as quoted by Derrida), writing was the “supplement to the spoken word”. Thus, here we have the opposition spoken word/writing again. Derrida questions whether or not writing was in fact a supplement to the spoken word.

At first blush at least, surely the spoken word did come before writing. However, despite the details of history in Derrida’s Of Grammatology, he wasn’t questioning the chronology here. It can be assumed, then, that Derrida did accept that, historically, the spoken word came before writing. (How could he not do so?) That wasn’t his point. His point is that when both writing and the spoken word exist together, it’s as if the chronology were irrelevant.

Signifier, Signified, and Saussure

Derrida represented the relations between a signifier, a signified and the logos in the following passage:

“[A] sign signifying a signifier itself signifying an eternal verity, eternally thought and spoken in the proximity of a present logos.”

In Derrida’s philosophy, a signifier can only signify another signifier, not anything external to writing. But, in the old style, a (forgive the phrasing) signifier signified a signified, which is in “proximity to a present logos”.

Derrida poetically said that it was believed (by philosophers) that the signified experiences a “fall” in its journey to the voice, and then to the signifier. He used the word “fall” because this process was represented in “medieval theology”. What’s more, the voice was deemed to be much closer to “the face of God” than writing.

As just seen, Derrida questioned binary oppositions when it came to the specific and important example of Ferdinand Saussure’s signifier and signified. So despite Saussure’s belief that the signifier and the signified are “two faces of one and the same leaf”, it’s still the case that “[t]his notion remains therefore within the heritage of that logocentrism which is also a phonocentrism”. It does so by virtue of the very fact that Saussure set it up as an opposition.

Derrida, on the other hand, didn’t privilege one half of this opposition (or any other opposition): he rejected the opposition itself. So Derrida interpreted Saussure as still privileging one half of his own opposition. In Derrida’s own words, Saussure’s signifier still has a

“absolute proximity of voice and being, of voice and the meaning of being, of voice and the ideality of meaning”.

Another way of looking at this is to say that the very use of the word “signified” suggested to Derrida that Saussure believed that the signified, well, exists. Derrida, on the other hand, believed that it didn’t exist. In other words, we don’t have two faces of one and the same leaf: we only have one… thing. However, that one thing isn’t the signifier either. That’s because a signifier signifies… something. To Derrida, that meant that we couldn’t simply erase the signified and be happy with the signifier. Instead, because they’re two faces of one and the same leaf, then both must go. (Of course, that didn’t that mean that Derrida never used the words “signifier” and “signified”.)

The Play of the Sign

Derrida wanted to free the signifier from the signified. Once the signifier (or writing) is free, then we have an “advent of [ ] play”. This play is what we have when written words are no longer obedient to the signified (or to the logos). Indeed, when Derrida wrote these words, he believed that “today such a play is coming into its own”. That meant that “the circulation of signs” is no longer “regulate[d]” to truth, the world, meaning, facts, etc.

Truth, the world, meaning, etc. are all polluted (or liberated by) the frank acknowledgement that they don’t exist outside the “play of the sign”.

Moreover, if you take Derrida’s position to its logical(!) conclusion (which Derrida himself did), then the very “concept of ‘sign’” has to go. That’s because you can’t have a sign without what that sign is a sign of. And what a sign is a sign of is itself already polluted by other signs (as well as by play).

Books and Texts

Another important duo of technical terms Derrida used is “book” and “text”. (They are everyday words which were given a technical meaning.) Put in simple terms (something which Derrida never did): a book’s contents are (or were) deemed to be about the world, reality, things, events, facts, etc. Texts, on the other hand, are about other texts. In Derrida’s Of Grammatology, books are also (supposed to be) about the signified, whereas texts are about the signifier.

In a controversial sense, the use of the technical term “text” is a commitment to some kind of linguistic idealism, whereas, to be crude, a belief in books commits readers to some kind of metaphysical realism.

Rather dramatically, Derrida announced the “death of the book”. And, as a corollary of that death, there must have been a “death of speech” (or of “so-called full speech”) too. (That’s if one accepts Derrida’s entire philosophy.)

Yet Derrida did write that “‘Death of speech’ is of course a metaphor here”. In other words, of course speech isn’t dead! (How could it be?) Instead, the superior status of speech (vis-à-vis writing) is questioned, and then rejected. Or, in Derrida’s prose, “we must think of a new situation for speech” in which it will be “subordinat[ed] within a structure” (i.e., a structure which includes writing and texts).

According to Derrida’s logic, however, writing and texts (like the signifier earlier) won’t thereby become the superior part of this structure (or a new “archon”). That’s because there are no such things as “full speech” and books in the first place. Thus, there’s no place for a hierarchy if parts of that hierarchy don’t exist in the first place.

In the end, then, there can’t be an opposition between speech and writing, book and text, signified and signifier, etc. either.

But let’s backtrack a little here.

The Logos

Derrida claimed that in the tradition of Western metaphysics, all (metaphysical?) significations “have their source in that of the logos”.

So what is the logos?

Derrida describes the logos in all sorts of ways. In the paragraph from which the words just quoted come from, Derrida was talking of the logos

“in the pre-Socratic or the philosophical sense, in the sense of God’s infinite understanding or in the anthropological sense, in the pre-Hegelian or the post-Hegelian sense”.

That’s a lot of senses. Derrida must have believed that all these senses shared something.

The words “the sense of God’s infinite understanding” seem the most straightforward here. Whether or not there is a God and His infinite understanding, this seems to be about a total and complete knowledge of all domains - or at least of any given domain. Perhaps we can conclude that the logos in the philosophical sense must have also involved a commitment to a total and complete knowledge (or understanding) of all domains — or a least of any given domain.

We can now ask the following question: What, exactly, is known or understood?

Is the logos a thing?

All this boils down to philosophers — and others — believing (at least in Derrida’s eyes) that they’re getting closer to the logos, or to truth, or to reason, etc. This is almost a literal closeness. However, this closeness took on many forms (logos, truth and reason have just been mentioned). We also have “the self-presence of the cogito, consciousness, subjectivity”. Here the mirror of nature appears again. In other words, if we can cleanse the mind of all its shit, then we can have both knowledge and truth. (Alternatively, through Husserl’s “bracketing” of consciousness, we can find essences… and much more.)

What can we draw from these references to the cogito and consciousness?

According to Derrida, they’re all ways to “debase[] writing”. Of course, Descartes never cleansed his mind of writing. However, he did claim to have (temporarily) cleansed his mind of all those traditional views, etc. which were expressed in writing. Writing itself wasn’t really concentrated on by philosophers in those days: simply what was said via writing. (In Saussure’s terms, most philosophers hadn’t managed to make the distinction between signified and signifier… although some had!)

The Rationalists, Rousseau, and Subjectivity

Derrida made all his highly-technical philosophy more concrete when he tied it to the rationalists of the 17th century. (Descartes has just been mentioned.) Specifically, he tied it to notion of subjectivity. He wrote:

“[T]he determination of absolute presence is constituted as self-presence, as subjectivity. It is the moment of the great rationalisms of the seventeenth century.”

Derrida then made a more explicit connection when he continued:

“From then on, the condemnation of fallen and finite writing will take another form, within which we still live…”

To sum up the above in very simple terms: the rationalists tied subjectivity to the logos. Writing, on the other hand, was still distanced from the logos.

Derrida then moved straight ahead to consider a philosopher who isn’t usually considered to be a rationalist: Rousseau. In this case, Derrida told us that “self-presence [ ] carries in itself the inscription of divine law”. [See here.] Indeed, Derrida said that Rousseau explicitly condemned writing. (This is unlike all the other philosophers Derrida considers, except, perhaps, Plato.) Derrida quotes from Rousseau’s The Essay on the Origin of Languages, in which it’s written that writing “‘enervates’ speech: to ‘judge genius’ from books is like ‘painting a man’s portrait from his corpse’”.

It would seem, then, that it could quite possibly be the case that Rousseau's position on writing inspired Derrida to take his overall position on these issues. After all, Derrida did tackle Rousseau — both here and elsewhere - in detail. [See here.]

All that said, Derrida also showed us that Rousseau qualified his own position when he brought in the notion of (to use Derrida’s words) “natural writing”. Derrida then quotes Rousseau sounding like a good rationalist:

“‘The more I retreat into myself, the more I consult myself, the more plainly do I read these words written in my soul [ ] I do not derive these rules from the principles of the higher philosophy, I find them in the depths of my heart written by nature in characters which nothing can efface.”

In many ways, this is all very similar to Rousseau’s fellow Frenchman, Descartes. (Derrida himself classed it as a “Platonic” position.)

Derrida Destroys Truth Too

Derrida wanted to “inaugurate[] the destruction [ ] of all the significations that have their source in that of the logos”. (Derrida used the term “de-construction” here.) One such signification is the “signification of truth”. Thus, truth isn’t a thing, an entity, an abstraction, correspondence between linguistic statements and facts, etc.: it’s a signification. Basically, it’s merely a word.

Thus, Derrida had wider aims other than merely dismantling the binary oppositions discussed (from various angles) so far. He also wanted to destroy truth. Thus, this dismantling of the binary oppositions of speech and writing, book and text, signified and signifier, etc. was just a means to destroy truth and Western metaphysics itself.

But what was all the above for?

Conclusion

To Derrida, it was all about “the destruction of the book”, which Derrida said was “now underway in all domains”. Indeed, Derrida admitted that this “violence” against the book is “necessary”. The destruction of the book, as has hopefully been shown, is also the destruction of truth, meaning, any distinction between words and things, and a whole host of other things too numerous to mention.

Note

(1) It’s surprising how much history of philosophy there is in the chapter ‘The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing’. The history of philosophy is something that many Continental philosophers have argued analytic philosophers ignore. (That might have been true once. See here.) Thus, some readers may be a little in the dark as to the accuracy of Derrida’s histories, as well as its complete relevance to the philosophical themes he draws out of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment