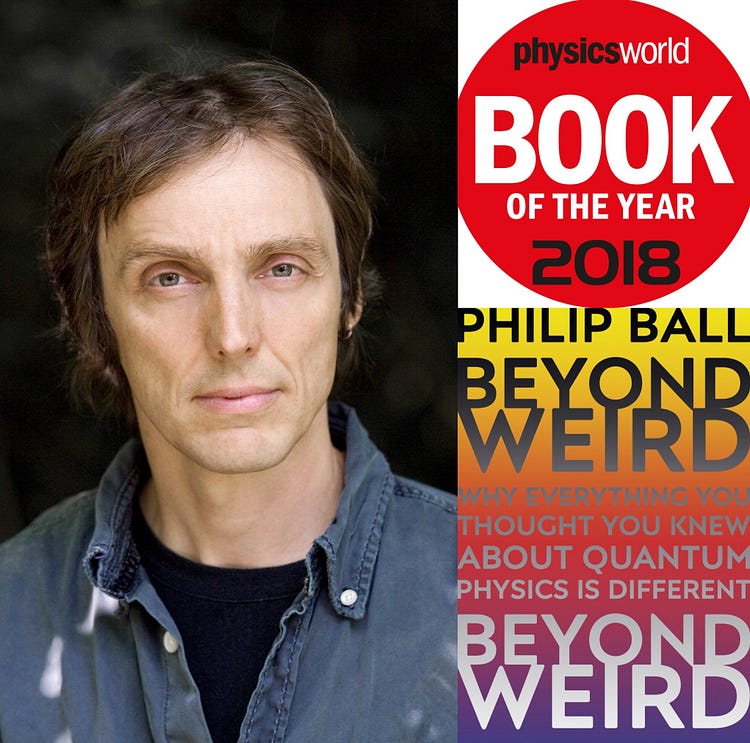

The science writer Philip Ball simply and graphically deflates the (to use his own word) “weirdness” of quantum mechanics in the following way:

“Not

‘here is a particle, there is a wave’

but

‘if we measure things like this, the quantum object behaves in a manner we associate with particles; but if we measure it like that, it behaves as if it’s a wave’

Not

‘the particle is in two states at once’

but

‘if we measure it, we will detect this state with probability X, and that state with probability Y’.”

The basic gist of all the above is that it isn’t the case that x is both a wave and particle. Instead, it’s that, according to different measurements, observations and experiments, it’s interpreted as being that way. Similarly, a particle isn’t in two states at once. Instead, according to one measurement, it’ll be in one state; and, according to another measurement, it’ll be in another state. So, in basic terms, it’s as if before any measurement, x was both a wave and a particle and/or in “two states at once”.

(Of course it’ll need to be specified exactly how measurements themselves turn the — as it were - noumenal x into a wave or particle or bring about this state rather than that state. But this isn’t the place to go into those details.)

All this is problematic for many scientists, all scientific realists and for the many laypersons who consider these issues. That’s because, according to Philip Ball again, “we’re used to science telling is how things are”. Basically, most laypersons (if not scientific realists) don’t think in terms of measurements, observations or experiments at all. Such people see these things as being peripheral to the scientific enterprise. They believe that such an enterprise is really about “what is”. To Niels Bohr and the many other physicists connected to the Copenhagen interpretation (yes, interpretation) of quantum mechanics, on the other hand, measurements, observations and experiments are both essential and ineliminable. (This position has an air of the obvious about it.)

Ball also stresses the difference between “is” and “if”.

Scientific realists focuses on what is. Scientific (for want of a better term) anti-realists focus on what will be the case if we do this or do that. The “Isness” is a result of the “Ifness”. However, if the Isness is actually a result of the Ifness, then realists won’t take it to be genuine (or true) Isness at all!

So is there an “Isness beneath the Ifness”?

There may well be.

But please tell me something about it.

You can’t.

The only way you can do so is via (or through) measurements, observations or experiments. And then, arguably, you’re no longer talking about Isness at all. Thus isn’t it the case that Isness is a (to use Nancy Cartwright’s words) “metaphysical pipedream”? Surely it can never be discovered or found. Strangely enough, around 250 years ago, the philosopher Immanuel Kant realised something very similar when he began to distinguish phenomena from noumena… But that’s another story.

No comments:

Post a Comment