In Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized, the philosophers James Ladyman and Don Ross give a clear account of the physics which underlies the problematic nature of seeing elementary particles as single things or objects. (Everything Must Go is a controversial and fairly well-known book — at least in philosophy.)

Firstly, Ladyman and Ross put the position of classical physics:

“[C]lassical physics assumed a principle of impenetrability, according to which no two particles could occupy the same spatio-temporal location. Hence, classical particles were thought to be distinguishable in virtue of each one having a trajectory in spacetime distinct from every other one.”

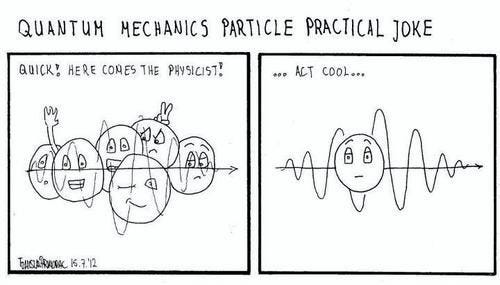

Clearly, in quantum mechanics (QM), many — or all — the assumptions in the classical picture are rejected. (Or, at the least, on many interpretations of QM all these assumptions are rejected.)

Take the notion of impenetrability.

Impenetrability

The “principle of impenetrability” is rejected by Ladyman and Ross.

On the classical picture, if particles are impenetrable, then that must mean that “no two particles could occupy the same spatio-temporal location”. However, if they are penetrable (or if the notion of impenetrability doesn’t make sense), then one can conclude that two particles “could occupy the same spatio-temporal location”.

Now one can immediately ask the following question:

If two particles can (or do) occupy the same spatiotemporal location, then is it correct to talk about two particles in the first place?

As a consequence of that question, the second part of the classical picture is rejected too. That second part (which follows from the first) is that

“classical particles were thought to be distinguishable in virtue of each one having a trajectory in spacetime distinct from every other one”.

Clearly, if the penetrability argument is true (i.e., two particles may occupy the same location), then each particle can’t be seen to have its own trajectory in spacetime. In other words, it will — or may — share its trajectory with another particle.

All this has the result (at least according to Ladyman and Ross) that the Leibnizian picture breaks down in the case of quantum-mechanical particles. On the other hand and according to Ladyman and Ross:

“Thus for everyday objects and for classical particles, the principle of the Identity of Indiscernibles is true [].”

So what about the notion of individuals?

Individuals

Ladyman and Ross then offer us two statements which they believe summarize the position of “standard metaphysics” on, if not particles, then on what they call “individuals”.

“There are individuals in spacetime whose existence is independent of each other. Facts about the identity and diversity of these individuals are determined independently of their relations to each other.”

The problem is how to take the word “independent” in the passage above.

One can accept the reality (or existence) of individuals yet also believe they that they aren’t (entirely) independent of other individuals. That is, the reality (or existence) of individuated objects and their lack of independence aren’t mutually exclusive. What’s more, one can accept the “identity and diversity of these individuals” yet also deny that such “individuals are determined independently of their relations to each other”. In other words, why does a commitment to individuals necessarily mean that one must also accept their complete independence from all other individuals (or from other events, processes, conditions, states, fields, systems, structures, etc.)?

In addition, it’s simply false that metaphysicians have accepted all that’s claimed in (i) above. Randomly, take the various monists and holists in the history of philosophy; as well as philosophers like F.H. Bradley and A.N. Whitehead. Such philosophers certainly didn’t believe that individuals are “independent of each other”.

What about Ladyman and Ross’s second statement?

They say that “standard metaphysicians assume” the following about individuals or particles:

“Each has some properties that are intrinsic to it.”

Here again what was said about claim (i) partly goes for claim (ii) as well.

Throughout the history of Western metaphysics there have been metaphysicians who’d now be classed as “anti-essentialists”. Indeed we could go back to Heraclitus (c. 535 — c. 475 BC) to find anti-essentialists (or at least to find proto anti-essentialists). In addition, we had the medieval nominalists. Come the 20th century, there’ve been many anti-essentialist metaphysicians and philosophers.

So what, in very basic terms, do essentialists (see essentialism) believe?

They believe that an individual “has some properties that are intrinsic to it”. However, here again it can be said that some/most of the ontologists who’ve (broadly speaking) accepted the bundle theory of individuals could also be classed as anti-essentialists in that they’d have denied the statement that each individual must have at least some intrinsic properties.

Discernibility and Individuality

One method for distinguishing two individuals (or two objects/particles) is basically W.V.O Quine’s reworking of Leibniz.

Quine called it “absolute discernibility”. Ladyman and Ross express his position this way:

“Quine called two objects [] absolutely discernible if there exists a formula in one variable which is true of one object and not the other.”

This is a reworking of Leibniz’s logical position (with the addition of references to “formulas”). Thus:

(x) (y) (F) (x = y ⊃. F (x) ≡ F (y).)

One obvious way in which a and b can be deemed to be “absolutely discernible” is if they “occupy different positions in space and time”.

Now for “relatively discernible” objects.

According to Ladyman and Ross,

“[m]oments in time are relatively discernible since any two always satisfy the ‘earlier than’ relation in one order only”.

This clearly makes a moment in time relational in nature (see relational theory). Or at least its relatively discernible nature is accounted for by its relational nature (i.e., “earlier than” and “later than”).

What’s just been said about time is similar to what can also be said about space (as well as about the “mathematical objects” which measure it). Ladyman and Ross write:

“An example of mathematical objects which are not absolutely discernible but are relatively discernible include the points of a one-dimensional space with an ordering relation…”

More precisely:

“[F]or any such pair of points x and y, if they are not the same point then either x > y or x < y but not both.”

In the above there’s a fusion of points in space with moments in time. Thus x and y are absolutely discernible because x is before (or “earlier than”) y or x is after (or “later than”) than y. In other words, x can’t be both earlier than and later than y (as well as vice versa) at one and the same time.

Now let’s take Ladyman and Ross’s definitions of discernibility and individuality. They write:

“The former epistemic notion concerns what enables us to tell that one thing is different from another. The latter metaphysical notion concerns whatever it is in virtue of that two things are different from one another, adding the restriction that one thing is identical with itself and not with anything else.”

At first glance, these characterisations come across as two different ways of saying the same thing. Clearly the second characterisation (“whatever it is in virtue of that two things are different from one another”) is ontological in character. The former (“what enables us to tell that one thing is different from another”) is, as Ladyman and Ross say, epistemic in character. However, don’t these two characterisations fuse? That is, in order to know “whatever it is in virtue of that two things are different from one another” one would need to employ the epistemic tools which “enable us to tell that one thing is different from another”. Thus the ontological question merges with the epistemological question (or vice versa).

We can also say that because of the spatial differences between Max Black’s two (identical) spheres (in his well-known thought experiment), sphere a and sphere b can only be classed as “weakly discernible” on Ladyman and Ross’s picture.

Ladyman and Ross make Max Black’s example more concrete (as well as scientific) by talking about two fermions (which are a mile apart) instead of spheres. According to Ladyman and Ross:

“Clearly, fermions in entangled states like the singlet state violate both absolute and relative discernibility…”

Fermions “in entangled states like the singlet state” (see singlet state) aren’t absolutely discernible because there are neither spatial nor temporal means to disentangle each fermion from other fermions. (Hence the technical term entanglement.) However, Max Black’s two spheres are also spatially indiscernible in that they’re in constant movement around a figure of eight. Thus sphere a would be continuously occupying a spatial point which had only just been occupied by sphere b — as well as vice versa. (The only way out of this would be to either literally or imaginatively freeze the movements of both spheres — though that would be unacceptable because it defeats the object of the thought-experiment.)

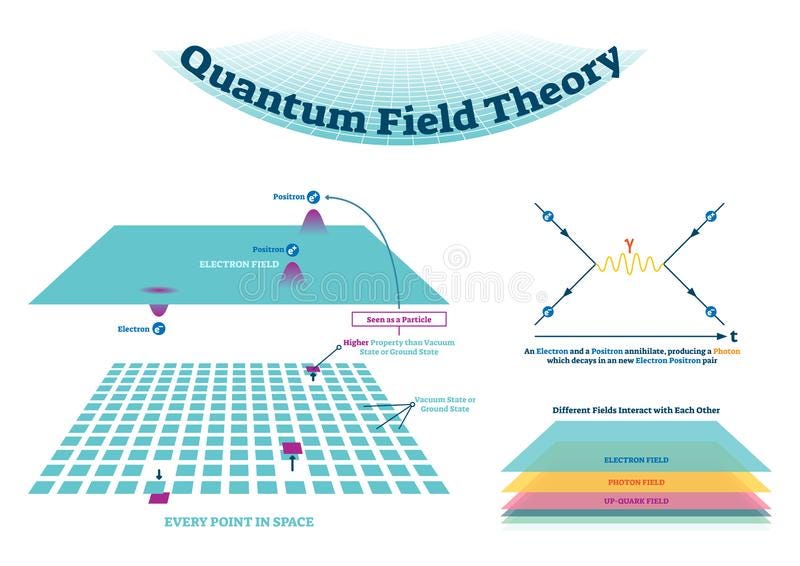

Fields and States

It can be seen that the notion of a field plays an important part in Ladyman and Ross’s philosophy.

The central argument is that fields and particles are intimately connected. Indeed they’re so strongly connected that a distinction between the two hardly seems warranted.

Ladyman and Ross’s position on the fields of physics can be traced back to — among others — Ernst Cassirer. (Cassirer died in 1945.) Indeed Ladyman and Ross have much to say about Cassirer. For example, they wrote the following:

“OSR [ontic structural realism] agrees with Cassirer that the field is nothing but structure. We can’t describe its nature without recourse to the mathematical structure of field theory.”

What Ladyman and Ross say about Ernst Cassirer’s position on objects is almost exactly the same as their own. Indeed it was also quantum mechanics which provided Cassirer with the motivation to reject “individual objects”. Ladyman and Ross write:

“Ernst Cassirer rejected the Aristotelian idea of individual substances on the basis of physics, and argued that the metaphysical view of the ‘material point’ as an individual object cannot be sustained in the context of field theory. He offers a structuralist conception of the field.”

One can firstly ask whether or not a commitment to the existence of objects is also automatically a commitment to “individual substances”; as well as to intrinsic (or essential) properties. (As stated earlier on in this essay.)

We can also ask whether or not these positions are equally applicable to objects in the “classical” (or macro) world.

Let’s put it this way.

Ernest Cassirer’s and Ladyman’s positions are far more acceptable when applied the the quantum world than when applied to the classical world (or to the world of experience). More precisely, all this is far easier to swallow in the “context of field theory” than it is in relation to, say, human beings (or persons), trees or cups.

There’s also the problem of distinguishing particles from the states or fields they “belong” to. Thus, in an example given by Ladyman and Ross, we can interpret a given field/particle situation in two ways:

i) A two-particle state.

ii) A single state in which two “two particles [are] interchanged”.

Since it’s difficult to decipher whether it’s a two-particle state or a single state in which two particles are interchanged, Ladyman and Ross adopt the “alternative metaphysical picture” which “abandons the idea that quantum particles are individuals”. Thus all we have are states. That means that the “positing [of] individuals plus states that are forever inaccessible to them” is deemed to be (by Ladyman and Ross) “ontologically profligate”.

Ladyman and Ross back up the idea that states are more important than individuals (or, what’s more, that there are no individuals) by referring to David Bohm’s theory. In that theory we have the following:

“The dynamics of the theory are such that the properties, like mass, charge, and so on, normally associated with particles are in fact inherent in the quantum field and not in the particles.”

In other words, mass, charge, etc. are properties of states or fields, not of individual particles. However, doesn’t this position (or reality) have the consequence that a field takes over the role of an individual (or of a collection of individuals) in any metaphysics of the quantum world? Thus does that also mean that everything that’s said about particles can now also be said about fields?

Particle Trajectories

On Bohm’s picture ( if not on Ladyman and Ross’s), “[i]t seems that the particles only have position”. Yes; surely it must be a particle (not a field) which has a position. Indeed particles also have trajectories (if probabilistically accounted for) which account for their different positions.

To Bohm (at least according to Ladyman and Ross), “trajectories are enough to individuate particles”.

It’s prima facie strange how trajectories can individuate.

Unless that means that each type of particle has a specific type of trajectory. In that case, the type trajectory tells you the type of particle involved in that trajectory.

Ladyman and Ross spot what they take to be a problem with Bohm’s position. That problem is summed up in this way:

If all we have is trajectories (as with structures), then why not dispense with particles (as individuals at least) altogether?

This is how Ladyman and Ross themselves explain their stance on Bohm’s theory:

“We may be happy that trajectories are enough to individuate particles in Bohm theory, but what will distinguish an ‘empty’ trajectory from an ‘occupied’ one?”

Here again Ladyman and Ross are basically saying that if all we’ve got are trajectories (which are part of the “structure”), then let’s stick with them and eliminate particles (as individuals) altogether.

Ladyman and Ross go into more detail on this by saying that

“[s]ince none of the physical properties ascribed to the particle will actually inhere in points of the trajectory, giving content to the claim that there is actually a ‘particle’ there would seem to require some notion of the raw stuff of the particle; in other words haecceities seem to be needed for the individuality of particles of Bohm theory too”.

If the physics of Ladyman and Ross is correct, then what they say makes sense. Positing particles seems to run free of Occam’s razor. That is, Bohm was filling the universe’s already-existing “ontological slums” with yet more superfluous entities.

One way of interpreting this is by citing two different positions. Thus:

1) The positing of particles as individuals which exist in and of themselves.

2) The positing of particles as part of package-deals which include fields, states, trajectories, structures, etc.

Then there’s Ladyman and Ross’s position.

3) If there are never particles in splendid isolation (apart from fields, states, etc.), then why see particles as individuals in the first place?

Ladyman and Ross are a little more precise as to why they endorse 3) above.

They make the metaphysical point that “haecceities seem to be needed for the individuality of particles of Bohm’s theory too” (see haecceity) . In other words, in order for particles to exist as individuals (as well as to be taken as existing as individuals), they’ll require “individual essences” (see individual essence) in order to be individuated. However, if the nature of a particle necessarily involves fields, states, other particles, trajectories, structures, etc., then it’s very hard (or impossible) to make sense of the idea that it could have an individual (or indeed any) essence.

(Can’t all this also be said about objects in the large-scale world too — that is, about human beings, tables, chairs and so on?)

In basic terms, then, all particles are parts of various package-deals. Particles simply can’t be individuated without reference to what’s called extrinsic or relational factors.

To Ladyman and Ross, this means that particles simply aren’t individuals at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment