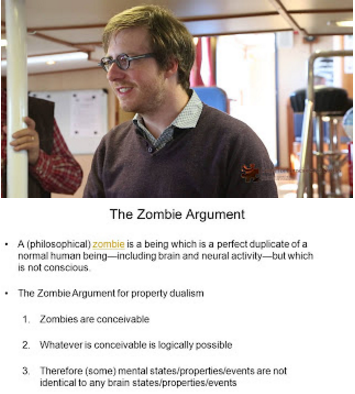

The philosophical notion of conceivability is at the very heart of the work of philosophers like David Chalmers and Philip Goff. Without it, their arguments against physicalism — and in support of the possibility of philosophical zombies - wouldn’t even get off the ground in the first place. In fact these philosophers wouldn’t even be widely known today if it weren’t for the importance they’ve placed on (philosophical) conceivability.

For example, in David Chalmers’ brilliant book, The Consciousness Mind (1996), there are comments and arguments about logical possibility and conceivability on almost every page. And this was the book which jumpstarted Chalmers’ career.

I even suspect that Chalmers and Goff would agree with this account of the importance they place on conceivability. That said, they probably wouldn’t word it in precisely the same in which way I have.

So it’s ironic that despite this importance given to distinguishing imagining any given x from conceiving of that same x, the philosopher Daniel Dennett (1942-) still asks the following question:

“Can you conceive of one? Can you imagine one? What is the difference?”

I doubt that Dennett is arguing that there’s no difference at all between imagining and conceiving any given x. Perhaps he’s simply claiming that it’s a difference that doesn’t really make (much of) a difference (i.e., to these specific issues).

I would also add that — in these cases at least — it’s not just that there’s no difference between conceiving and imagining any given x (or that the difference isn’t important), it’s that nothing may be conceived of in the first place — at least in the case of philosophical zombies! (See my Can You Conceive of a Philosophical Zombie… or a Million-Sided Object? | by Paul Austin Murphy | Curious | Medium.)

In addition and to use Dennett’s words, “we are entitled to ask them how they would know” that they’ve conceived of any given x.

Dennett’s question above is about those people who “say they can conceive of (philosophical) zombies”. So we can ask how they know that they’re conceiving a zombie rather than (merely) imagining one. That is, “[w]hat is the difference” between conceiving of a philosophical zombie and imagining a philosophical zombie?

It may be worse than that: perhaps neither conceiving nor imagining will help us distinguish a human being who actually instantiates experience (or consciousness) from a philosophical zombie. So whichever option we choose, there may still be a more particular problem when it comes to philosophical zombies.

(Note: If it’s accepted that imagining and conceiving are so different, then surely we have no right to say that the very same x has been both conceived of and imagined. In other words, what does the conceiving of any given x and the imagining of that same x share?)

Nearly all of this dates back to Descartes.

Descartes on Imagining and Conceiving

The 17th-century French philosopher Descartes (1596–1640) emphasised — in strong terms — this distinction between imagining and conceiving. The following is Daniel Dennett putting Descartes’ position:

“Just imagining something is not enough — and, in fact, Descartes tells us, it is not conceiving at all. According to Descartes, imagining uses your (ultimately mechanistic) body, with all its limitations (nearsightedness, limited resolution, angle, and depth); conceiving uses just your mind, which is a much more powerful organ of discernment, unfettered by the requirements of mechanism.”

So here we have a concern with distinguishing our imagining any given x and our conceiving of that same x. Just as relevantly, that distinction is tied very strongly to a dualist (or, more widely, a non-physicalist) explanation of why the two are so dissimilar. And it just so happens that the contemporary philosophers David Chalmers (1966-) and Philip Goff also incorporate dualism (or at least anti-physicalism) into their overall philosophies (more of which later).

In the case of Descartes, it’s the non-physical mind (which is a “much more powerful organ of discernment”) that allows us to conceive of x; whereas the “ultimately mechanistic body” (“with all its limitations”) allows us only to imagine that same x.

Thus the non-physical mind is necessary — at least according to Descartes — for conceiving of anything. In parallel, if we focus on (mere) imagination, then we’re only focussing on the body. And the body (with all its limitations) is not enough for the conceivings which Descartes had in mind.

So what did Descartes have in mind?

In this instance at least, Dennett tells us that Descartes

“offers a compelling example of the difference: the chiliagon, a regular thousand-sided polygon”.

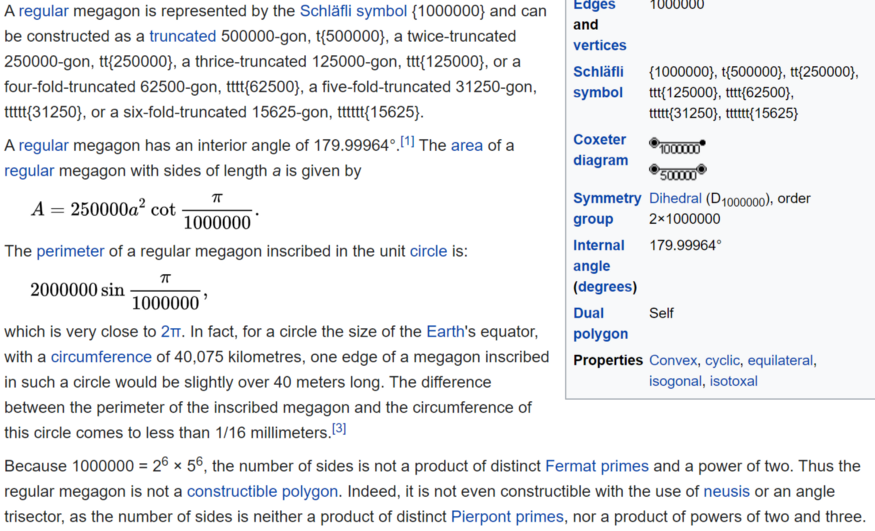

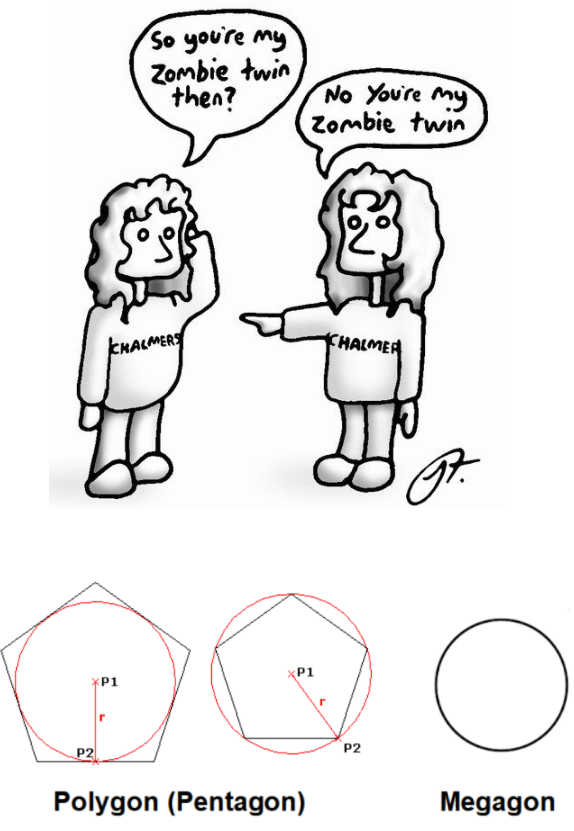

And guess what — Philip Goff also focussed on polygons when he discussed conceivability. Except, in his own case, he ups the ante and cites — as a relevant example — the case of a million-sided polygon: a megagon! (See later section.)

Dennett goes into more detail about Descartes’ position on conceiving. He writes:

“Descartes doesn’t tell you to perform such constructions; to him conception, like imagination, is a kind of direct and episodic mental act, glomming without bothering to picture, or something like that.”

Basically, the best (if somewhat oxymoronic) way of putting Descartes’ position is to say that the conceiving (or “conception”) of any given x is an act of imagination which doesn’t actually use (or include) any mental images!

This raises the question:

Once we take away all the (mental) images, then what do we have left?

Conceiving and Intuition

Dennett’s description of Descartes’ position makes it seem that the conceiving any given x is very similar to the philosophical notion of intuiting (or having “direct insight” into) such an x. This is especially the case when Dennett says that these kinds of conceiving are examples of “glomming without bothering to picture”.

Thus when Descartes conceived of a chiliagon it might have been like a (as it were) Gödelian mathematician intuiting the truth of an unprovable statement (see here). And consider too a mathematician like Roger Penrose (1932-) who plays down “picturing” and even “words” when it comes to gaining access to mathematical truths in the platonic realm. (Penrose also plays down words and pictures when he does mathematics generally.) For example, Penrose also seems to go beyond purely mathematical Platonism when he stated the following:

“[I] find words almost useless for mathematical thinking. Other kinds of thinking, perhaps such as philosophizing, seem to be much better suited to verbal expression. Perhaps this is why so many philosophers seem to be of the opinion that language is essential for intelligent or conscious thought!”

Alternatively, Descartes’ conceivings might have been like the philosopher Laurence BonJour’s own direct insights into metaphysical necessities — those necessities which are true of the physical world itself.

Basically, then, Dennett’s account of Cartesian conceiving (i.e., as a “kind of direct and episodic mental act”) seems like a perfect description of an act of intuition or direct insight.

That said, Dennett’s final words are perhaps the most important (or relevant) to this discussion. (After all, much has already been written on Gödelian and other kinds of intuition.) Dennett concludes:

“You somehow just grasp (mentally) the relevant concepts (SIDE, THOUSAND, REGULAR, POLYGON), and shazam! You’ve got it. I have always been suspicious of this Cartesian basic act of conceiving.”

Now what exactly is it to “grasp (mentally)” the concepts SIDE, THOUSAND, REGULAR and POLYGON? In addition, don’t these concepts need to be (as it were) fused together in order to grasp a chiliagon? After all, whatever conceiving of the concept SIDE, THOUSAND, REGULAR or POLYGON separately consists in, these concepts still need to be stuck together in order to grasp the broader concept — CHILIAGON.

What is it to Conceive of a Philosophical Zombie?

Perhaps Descartes was on much stronger ground when he discussed the conceiving of a chiliagon than David Chalmers and Philip Goff are when they discuss the conceiving of a philosophical zombie. Or the very least that can be said is that a chiliagon is in a different logical space to a philosophical zombie.

But, again, what is it to conceive of a philosophical zombie? What is the mental or abstract content of such an act of conceiving?

Dennett picks up on this in the following way:

“When people say they can conceive of (philosophical) zombies, we are entitled to ask them how they know. Conceiving is not easy!”

More particularly, how does, for example, a dualist, anti-physicalist or anyone else know that he’s conceived of a philosophical zombie? How do we know that he has conceived of a philosophical zombie? In addition, how does he (to use Michael Dummett’s term) “manifest” his act of conceiving of a zombie to others? What if it’s a thoroughly private act? And, if it is private, then what status could it possibly have when it comes to establishing a metaphysical position or thesis?

We can get even more fundamental here: What is it to conceive of… anything? This isn’t to argue that we don’t conceive of things. It’s just a demand for some kind of account.

In any case, Dennett give some examples of things which he believes are difficult to conceive. He writes:

“Can you conceive of more than three dimensions? The curvature of space? Quantum entanglement?”

The least that can be said is that Dennett’s examples are all very different.

So perhaps we can’t imagine more than three dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement; though we can conceive of them.

Dennett continues (as already quoted):

“Just imagining something is not enough — and, in fact, Descartes tells us, it is not conceiving at all.”

The thing is that the existence of more than three dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement must have been conceived of — many times — because they’re accepted notions in physics. Indeed they’re even accepted aspects of the physical world (or at least two of them are)! That is, no one has ever seen or observed these things. And, depending on definitions, not one has ever imagined these things either. So all we have left is to conceive of more than three dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement.

Thus Descartes, Goff and Chalmers may be onto something here!

Yet even here conceiving of these things may be in a different logical space to conceiving of a philosophical zombie. After all, there are a lot of equations, natural laws, theories, indirect/direct observations, experiments, etc. to account for extra dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement. Are there a lot of equations, natural laws, theories, experiments, indirect/direct observations, experiments, etc. to account for philosophical zombies?

Of course not.

And that’s primarily because Goff and Chalmers themselves accept that philosophical zombies are only a logical possibility. Thus there are no equations, direct/indirect observations, natural laws, experiments or physical theories which account for the existence of philosophical zombies.

Philip Goff on Anil Seth’s Confusing Imagining and Conceiving

As stated, both David Chalmers and Philip Goff make much of the distinction that we must make between (merely) imagining x and conceiving of that same x. To them, this difference is extremely important.

For example, the following is Philip Goff writing about those academics who confuse (or conflate) the two:

“The zombie argument is generally known in the academic philosophical literature as the ‘conceivability argument.’ I think this is something of a misnomer, as it suggests that the argument has something to do with what can be imagined.”

So not only does Goff believe that the word “imagine” is misleading: he also believes the same about the word “conceive. Of course that’s primarily because Goff believes that people conflate (or confuse) imaginability with conceivability.

As it is, Goff doesn’t care that much about merely imagining any given x: his position is about the conceiving of that x.

(Again: if it’s accepted that imagining and conceiving are so different, then surely we have no right to say that the very same x has been both conceived of and imagined. In other words, what does the conceiving of any given x and the imagining of that same x share?)

So Goff spots such a confusion (or conflation) in the arguments of the cognitive neuroscientist Anil Seth (1972-).

Goff firstly quotes Anil Seth’s own words in the following way:

“‘Conceivability arguments are generally weak since they often rest on failures of imagination or knowledge, rather than on insights into necessity. For example: the more I know about aerodynamics, the less I can imagine a 787 Dreamliner flying backwards. It cannot be done and such a thing is only ‘conceivable’ through ignorance about how wings work.’”

And the following is Goff’s response to that passage:

“The zombies argument is concerned with logical possibility, whereas Seth’s example deals with natural possibility. It is inconsistent with the laws of nature for a 787 Dreamliner to fly backward, and one appreciates this as one learns about the relevant laws of nature. But it is certainly not contradictory for a 787 Dreamliner to fly backward; if the laws of nature had been very different, such a thing might have been possible. In other words, a 787 Dreamliner flying backward is not naturally possible but it is logically possible.”

Goff derives what he calls a “logical possibility” (see here) from what he has conceived. And, in this case at least, what he conceived didn’t abide by “natural possibility”. In other words, Goff’s conceivable x outruns the natural. Indeed his conceivable x even outruns the actual (or the real).

Conclusion

Let’s forget about what is logically possible for the moment because — to Goff — it’s a product of what is conceivable. This means that the first port of call is the act of conceiving of any given x.

Yet the case against being able to conceive of a philosophical zombie has little (though not nothing) to do with with a belief that mental images (or imagery of whatever kinds) are required.

Take the case of a megagon again.

No one can imagine what a megagon looks like because it looks like a circle. The lack of conceivability in this case is down to not knowing all the mathematics. (Thus non-mathematicians must rely on the testimony of mathematicians when it comes to the — abstract — existence of a megagon; and the same goes for Daniel Dennett’s earlier examples of curved space and entanglement.)

This situation may well be passed on — at least to some extent — to the case of a philosophical zombie.

Simply writing the words “A zombie is exactly like a human being in every respect — except it has not consciousness”, and then thinking about those words and noting that they don’t contain a contradiction, is not to actually conceive of a philosophical zombie at all.

Philip Goff particularly makes the philosophical notion of conceivability seem purely logical in nature. That’s why he often mentions “contradictions”. Yet it can’t all be purely logical. Using words like “zombie”, “human being”, “experience”, “metaphysics”, “behaviour”, etc. means that Goff has automatically gone way beyond (pure) logic. In other words, Goff is using terms which are extremely loaded — from a philosophical point of view. And it can therefore be argued that a purely (as it were) logical conceiving (or reading) of a philosophical zombie no longer does the trick.

Yet Goff is still attempting to make it seem that what he’s arguing is purely logical. If it were purely logical (say, only a matter of Ps, Qs and logical operations), then a pure conceiving of a (logical) x would be fine. But we’re supposed to be conceiving of philosophical zombies!

So has Philip Goff actually conceived of a philosophical zombie (or a megagon) in the first place?

No comments:

Post a Comment