Searle argues that it’s not that “brain processes cause consciousness”. It’s that “consciousness is itself a feature of the brain”. A loose analogy is a table’s weight causing an indented rug. The table’s weight on the rug and the indentation occur at one and the same time.

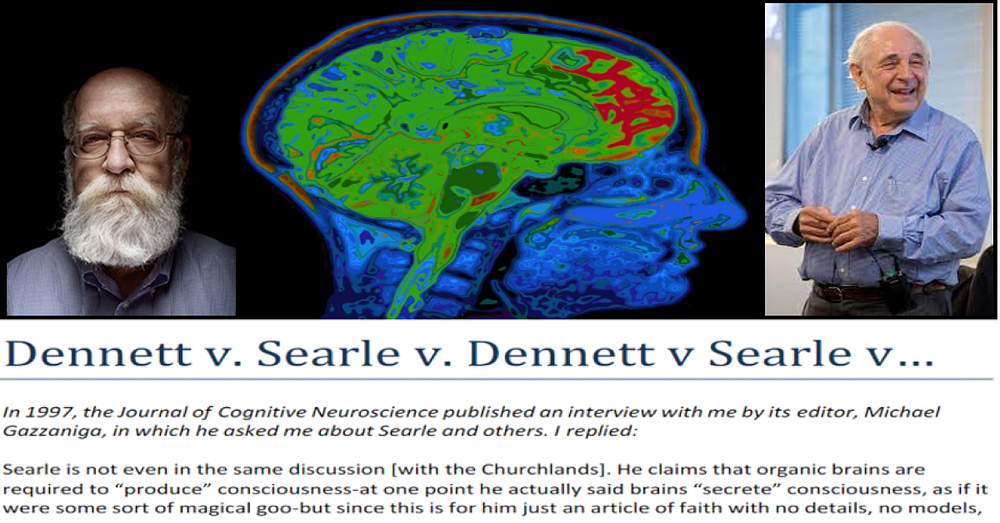

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett (1942-) once claimed that John Searle’s position is that the brain “secretes” consciousness. I suspect that Searle would argue that consciousness can’t be secreted out of anything — even out of the brain. That’s because Searle sees consciousness as a higher-level attribute of the brain — yes, of the brain. This means that the idea of any secretion of consciousness out of a brain it is already part of doesn’t really make sense.

[It seems that someone — perhaps Dennett? — once said to Searle: “It sounds like you’re saying the brain ‘secretes’ consciousness the way the stomach secretes acid or the liver.” Searle replied: “I have never claimed that [].”]

So what about the word “cause”?

If it can be stressed (as Searle does) that consciousness is a higher-level feature of the brain, then how can the brain cause consciousness?

The problem here, according to Searle, is that many people have a misconception about causation — at least when it comes to the brain causing consciousness.

The most important point which Searle makes (in this discussion of consciousness) is that causation needn’t be seen in the following temporal terms:

a cause C followed (in time) by effect E

Here we have two things: a cause followed by an effect. That is, the cause occurs at time t¹ and the effect occurs at tⁿ. This surely implies a kind of dualism for the simple reason that the brain’s cause-events occur before the effect-event that is consciousness (or a conscious state). Thus these two things (i.e., brain processes and consciousness) must be separated in that the former causes the latter. However, what if we can have processes which don’t entail a cause followed by an effect? That is, in which the processes of consciousness occur at the very same time as the brain processes.

Searle gives an example of a heavy table and the impression it makes on a rug.

This isn’t a question of the following:

the table-pressure-event (or state) causing the indented-rug-event (or state).

The weight of the table and the indented rug occur at one and the same time. Yet this is still a casual process. However, it’s not a case of a cause followed by an effect. It’s a causal process of the weight and the indentation occurring at one and the same time.

As Searle puts it: the gravitational force of the table shouldn’t be taken as an event which occurs before the indentation of the rug which is under it. Moreover, Searle states that “gravity is not an event” at all — it’s a force which is always there.

Searle’s next example is about tables and their solidity.

It can be said that the density (or nature) of the table’s molecules doesn’t cause the “solidity of the table”. That is, we don’t have a cause (i.e., the molecules and their behaviour) followed by an effect (i.e., the solidity of the table). Instead, whenever there are certain kinds of molecules of this specific density and structure, then we’ll also have a solid table. Such molecules don’t come first and then cause the solidity of the table. That last possibility would mean that there was a point in which we had that very same table (made up of the same molecules and the same structure); but in which the table wasn’t solid (say, it was fluid or floppy). Instead, as soon as we have that configuration and that set of molecules, we also have the table’s solidity. The one doesn’t come before the other.

That said, it’s still the causal processes of the molecules which are responsible for the solidity of the table. That is, we still have causation and causal processes. It’s just that we don’t have a cause followed by an effect.

One can see where Searle’s line of argument is going here.

It can now be argued that we shouldn’t see the brain’s processes (or states) as causes which bring about the processes (or states) of consciousness. Instead, we have brain processes (or states) and consciousness at one and the same time. That is, the brain’s processes (or states) don’t come before the processes (or states) of consciousness (or before consciousness itself). Both occur together.

Searle himself writes:

“Lower-level processes in the brain cause my present state of consciousness, but that state is not a separate entity from my brain; rather it is just a feature of my brain at the present time. [It’s not] that brain processes cause consciousness but that consciousness is itself a feature of the brain [].”

It can still be argued that the “lower-level processes in the brain cause my present state of consciousness”. So the word “cause” can still be used. However, we don’t have the following:

causes (or brain processes) which comes before an effect (consciousness or a mental state)

Consciousness (or a conscious state) “is not a separate entity from my brain”. It is, instead, “a feature of my brain”.

So Searle’s position isn’t too unlike Donald Davidson’s notion of “conceptual pluralism” (as expressed in his anomalous monism) squared with his “substance monism”. That is, the brain and consciousness are seen as being part of the same (loosely) substance — if with different features or properties which are characterised both from the subject’s inside and from the third-person outside. That is, we can apply different concepts to consciousness (or mind) which we wouldn’t apply to the brain itself. However, consciousness it still just a “feature of the brain”. It’s not something different. It’s not another substance.

So this argument works against mind-body dualism. However, it’s not a case of reductive physicalism either. Instead, Searle simply denies the duality of brain and consciousness (or matter and mind) in the first place.

And because Searle’s position on causation is (perhaps) odd when it comes to this notion of atemporal causation, then it may be wise to finish with citing what another philosopher thinks of it.

Take Nick Fotion. He tells us that Searle’s theory

“shows that the biological mechanisms on the lower level of the diagram have their causal effects on the upper level not over a period of time”.

Fotion continues:

“The emergent changes on the upper level are simultaneous with respect to what happens (vertically) below. Such is not the case when the mind affects the body on any level.”

Of course the central problem here is one of making sense of atemporal causation. That’s primarily because it’s usually believed that a sequence in time is built into the very notion of causation (or causality) — even when it comes to “backward causality”. What’s more, it seems that Searle could argue just about everything he does argue without also employing the notion of causation (or using the word “cause”). That is, he could argue that brain processes occur at the very same time as their — parallel? — conscious states without bringing causation on board at all.

All that said, this particular issue must be tackled at another time.

No comments:

Post a Comment