To begin with, it can easily be doubted that any flesh-and-blood relativist has ever actually claimed that Albert Einstein’s Special Relativity (SR) is itself an example of philosophical, moral or political relativism. Instead, the best that’s been argued is that some of the positions advanced in that theory (if amended somewhat) are applicable across the board.

Moreover, the word “relativity” is more likely to be used than “relativism” (or “relativist”) by postmodernists, post-structuralists, constructionists, etc. For example, the works of Jean Baudrillard and his commentators are liberally peppered with the word “relativity” (see here.)

Added to that is the fact that hardly any theorist, philosopher or political activist has ever classed himself as a “relativist”. (Perhaps, in these contexts at least, self-descriptions don’t really matter that much.)

In any case, the following passage displays some of the problems which will be tackled in this essay:

Firstly, in the passage above there’s an explicit rejection of the “relativist” interpretation of Einsteinian Relativity when the author says that

“most persons may interpret that Einstein is saying that everything in the universe is relative, but his work is of the position that everything is not relative, rather everything is relative from the observer’s frames of reference”.

Yet isn’t that precisely what the relativist argues — that “everything is relative from” the subject’s point of view? In other words, does using the words “observer’s frame of reference” (rather than “subject’s point of view”) really make that much of a difference — at least outside the precise context of Einstein’s own physics?

The writer then goes on to conclude:

“[T]herefore [Einsteinian Relativity] brought in more insightful understanding of postmodernist model of reality in science.”

Of course it’s true that there’s no explicit mention of moral or political relativism here — but he does tie Einsteinian Relativity to postmodernism. And the fact remains that no postmodernist philosopher (or theorist) I know has been at all concerned with “frames of reference” as exclusively found in physics. In other words, it’s clear here that such postmodernists, etc. were hoping to apply Einstein's findings to domains far outside physics. (Jean Baudrillard — as mentioned in parenthesis earlier - is a good example of this.)

Against Relativism

The American journalist and author Walter Isaacson (1952-) sums up the (as it were) non-relativist reality of Einstein’s Relativity in the following words:

“In both his science and his moral philosophy, Einstein was driven by a quest for certainty and deterministic laws. If his theory of relativity produced ripples that unsettled the realms of morality and culture, this was not caused by what Einstein believed but by how he was popularly interpreted.”

In addition to the above, the British historian Paul Johnson (1928-) made similar points in the following passage:

“At the beginning of the 1920s the belief began to circulate, for the first time at a popular level, that there were no longer any absolutes: of time and space, of good and evil, of knowledge, above all of value. Mistakenly but perhaps inevitably, relativity became confused with relativism.”

Indeed, Einstein’s best-known quote - “God does not play dice” — is hardly a claim of any kind of political, moral or philosophical relativist. Moreover, Einstein was a vocal and long-standing scientific realist. (Special Relativity, of course, predates the “quantum revolution” of the 1920s and wasn’t usually directly tied in with it — at least not in the early days.)

Yet Einstein-the-realist can still easily be squared with Special Relativity.

So it’s hugely ironic that poststructuralists, postmodernists, constructionists, etc. have used Albert Einstein’s Special Relativity as a means to bolster their own philosophical, epistemic or political theories of relativism. (That’s even though they’ve rarely used the actual word “relativism” about their own positions.) Indeed, using (or misusing) SR for relativism began well before any post-1960s postmodernists, etc. got hold of it. Einstein himself, for example, was disturbed by the fact that his SR was said to gave rise to some kinds of modern art and to moral relativism (see here). In this case, however, unlike postmodernists, etc. using SR for relativism, Einstein’s SR was thought to have actually given rise to various culturally, politically and philosophically relativist positions. That is, it was Einstein’s SR itself that was blamed (or sometimes praised) for such things.

Indeed, there was even more grist to the relativists’ mill when Einstein took a stand on absolutes. Einstein did so in the following passage:

“The ‘Principle of Relativity’ in its widest sense is contained in the statement: The totality of physical phenomena is of such a character that it gives no basis for the introduction of the concept of ‘absolute motion’; or, shorter but less precise: There is no ‘absolute motion.’ [].”

… Well, as you can see, Einstein didn’t actually take a position on absolutes (as an abstraction) at all . He took a position on “absolute motion”… absolute time, absolute space, etc — as indeed did Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) long before him (see here).

Yet, despite all that, one main point of the Special Relativity was to demonstrate that

“the laws of physics work the same for everyone, regardless of how they’re moving through space”.

So Einstein did indeed stress various and many relativities (the precise kinds will be discussed in a moment) in order to demonstrate universality and constancy. This means that what was deemed to be relative by Einstein was mainly a means to that end.

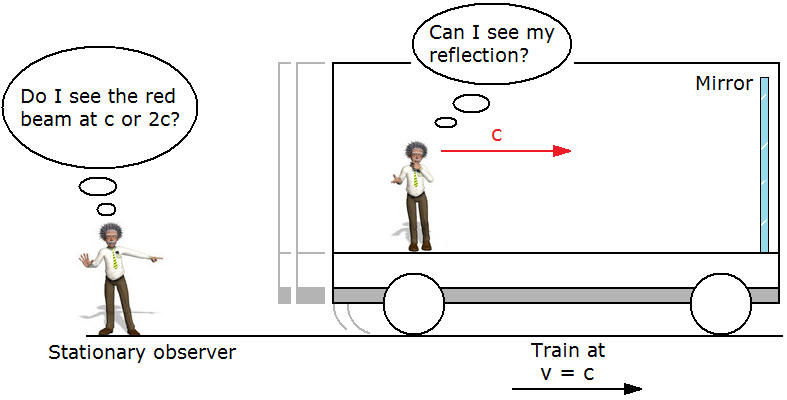

More specifically, with SR we have various relativities alongside the universal constant that is the speed of light (c). In other words, the speed of light doesn’t change relative to the motion of the object which is emitting the light (or light itself) or the person who’s observing that light. So c is constant even though everything else can and does change.

So even though time, position and motion are relative , the laws of physics are the same in all cases. And, as we’ve just seen, so is the speed of light. Another ways of putting this is to say that even though there are many genuine relativities (as well as constant change), none of these things change the universal and constant nature of the laws of physics themselves — at least not in Einstein’s view.

That said, and taking on board all the above, the closest one could come to justifying any connection between Einstein and relativism was his brief embrace of what was once called operationalism.

Operationalism

The odd thing about Einstein’s (early) operationalism is that in many ways Einstein has always been seen as the supreme example of a theoretical physicist and exponent of many thoughts experiments. (See Einstein’s thought experiments here.) So perhaps this reference to operationalism is all down to two different stages in Einstein’s career. Alternatively, perhaps it’s simply about different ways of tackling the same problems in physics — at any stage in anyone’s career.

Primarily, then, an “operationalist” stance on physics stresses the role of the subject (or observer) and his/her “operations” (e.g., experiments, tests, observations, etc.). And, indeed, operationalism could be seen in the Copenhagenist stress on experiments, predictions and observations in the 1920s and 1930s — i.e., rather than on “reality” (or “metaphysical reality”). This stress on experience can be traced back to the empiricists of the 18th century — if not well before that.

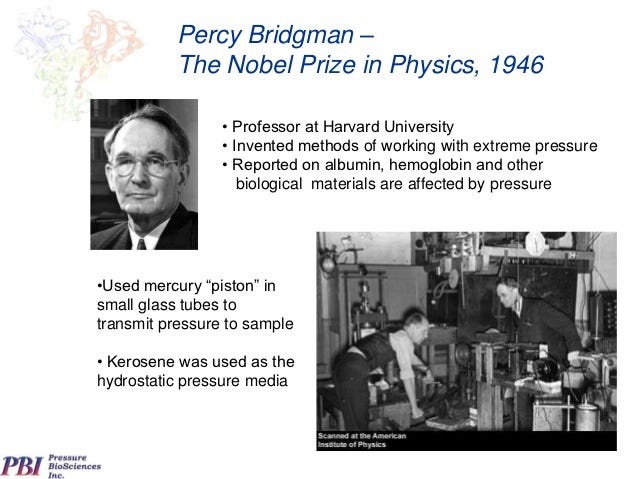

Yet many commentators have also stressed Einstein’s own problems with operationalism. Indeed, the main early exponent of operationalism, Percy Williams Bridgman (1882–1961), once stated the following words:

“Einstein did not carry over into his general relativity theory the lessons and insights he himself has taught us in his special theory.”

In addition to that, other commentators have said that Einstein’s “operationalist remarks” weren’t an attempt to advance a specific philosophical position on physics. And, as already hinted at, Einstein did indeed move away from operationalism after his General Relativity of 1915.

So Bridgman (primarily in his book The Logic of Modern Physics of 1927) was retrospectively providing a detailed philosophical account of all those mentions of “clocks”, “measuring rods”, “rigid bodies” and frames of reference in Einstein’s published words — see here. (Note that Bridgman’s book was written some 12 years after Einstein’s General Relativity and some 23 years after Special Relativity.)

Despite that and according to Bridgman, Einstein’s (early) work did nonetheless stress the need to link all scientific concepts to experimental procedures. (This was certainly something the Copenhagenists also stressed in the 1920s and 1930s.)

In more philosophical and fundamental terms, operationalism — just like the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics — had nothing to say about “objectivity” or the “objective world”. Indeed, this operationalist position can be directly tied to Einstein’s SR in that, say, length and mass weren’t seen as being absolute properties. Specifically, in Einstein’s SR, length is entirely dependent on the ruler used to measure an object, specific reference frames and what number is then given to that measurement. Mass too was — and still is — deemed relative to velocity, etc.

What’s more, an operationalist stance — despite Bridgman’s earlier words — can also be detected in Einstein’s General Relativity. (Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that an operationalist interpretation of General Relativity can be given.) After all, Einstein’s well-known distinction between inertial mass and (universal) gravitational mass is made in terms of “operational definitions”. (Einstein himself never used these two words.) That is, inertial mass is first noted when an operation is carried out. And that operation is the application of a force to a given mass (or object) and then observing its acceleration. (All this is in accord with Newton’s Second Law of Motion.) Similarly, gravitational mass is first noted when an operation is carried out. Yet this time the operation is putting the same object (or perhaps a different one) on a scale to insure a balance which disregards force and acceleration.

So here we have two different operations on a given mass (or given object) which produced the same result. And thus we had Einstein’s Principle of Equivalence.

Having stated all the above, this essay will now advance the position that the denial of literally any connection whatsoever between Special Relativity and (moral, philosophical or political) relativism is far too strong a stance to take.

Is Special Relativity at Least Partly Relativist?

According to Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont, one person who was at least formerly seen (by some commentators) as a postmodernist or poststructuralist, Bruno Latour (1947-), did make a correct distinction between Einsteinian Relativity and relativism. Thus:

“[] Latour draws an eminently sensible distinction between ‘relativism’ and ‘relativity’: in the former, points of view are subjective and irreconcilable; in the latter, space-time coordinates can be transformed unambiguously between reference frames.”

Yet there most certainly is an element of the “subjective” (or a stress on experience) in Special Relativity — but simply (as already stated) as a means to an end.

Philosophically, it can be argued that even if — or even though — “points of view are subjective”, then that doesn’t also mean that they’re (always) “irreconcilable”. Indeed, from that very subjectivity (or at least from the recognition of that subjectivity) one can work towards intersubjectivity. (This squares with Einstein’s own position in his SR.) To use Sokal and Bricmont’s own words, that intrinsic and given subjectivity can itself “be transformed unambiguously between reference frames”. Moreover, even the reference frames of physics are chosen from a subjective standpoint. That is, intersubjective reference frames firstly arise from the many previous subject-based choices of reference frames.

More fundamentally and as many philosophers — of many different persuasions (e.g., from empiricists to idealists) — have argued, the first port of call is always one’s own consciousness or experience. Thus, it’s where laypersons, theorists or scientists go from their subjectivity (or personal experiences) that matters — as Einstein himself (kinda) indirectly argued in his Special Relativity. In other words, Einstein explained how to unite different subjectivities (or experiences) together in order to advance various projects and theories within physics… not within morality, politics or philosophy.

No comments:

Post a Comment