“A world of signs without fault, without truth…” — Derrida

It must immediately be said that the problem with writing a negatively critical essay on Jacques Derrida is that the French philosopher didn’t really give (or allow) his readers any means to challenge his ideas or words. And by the words “negatively critical” I mean anything written by someone — or by anyone — on the outside of Derrida’s academic or intellectual milieu of admirers and followers.

That small amount said, more on this issue will be found in my forthcoming essay, ‘Jacques Derrida the Philosophical Joker’.

Jacques Derrida on What Deconstruction Isn’t

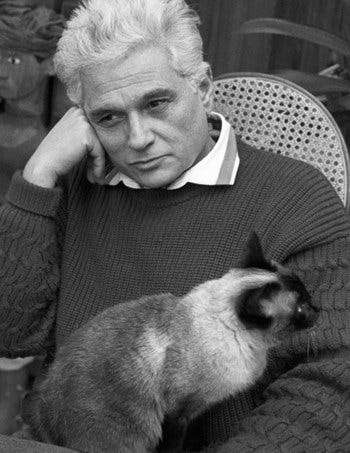

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) himself summed up the central theme of this essay. He did so in his ‘Letter to a Japanese Friend’ (1983); in which he wrote the following words:

“All sentences of the type ‘deconstruction is X’ or ‘deconstruction is not X’ a priori miss the point, which is to say that they are at least false. As you know, one of the principal things at stake in what is called in my texts ‘deconstruction’ is precisely the delimiting of ontology and above all of the third person present indicative: S is P.”

It can be seen that Derrida simply and directly contradicted himself in the passage above — which he might very well have allowed himself to do!

He told us that deconstruction isn’t X, it isn’t not-X, and that it isn’t Y. And then he even warned us against stating what deconstruction is. Yet he then went straight ahead and told us… what deconstruction is!

So what did Derrida believe that deconstruction is — at least in this instance? This (to requote):

“[D]econstruction is precisely the delimiting of ontology and above all the third person present indicative: S is P.”

Now if that isn’t telling us what deconstruction is, then I don’t know what is. Of course, deconstruction may not only be “the delimiting of ontology”; but surely that delimiting is at least a part of what deconstruction is.

In any case, this passage from Derrida fails in almost every other respect too. Yet it will of course be argued by deconstructors and other fans of Derrida — either directly or in arcane prose— that it only fails from a logocentric perspective! So, as stated briefly in the introduction, as someone firmly on the Outside of the academic and intellectual milieu which surrounds Derrida and his work, it is (as it were) a priori guaranteed that I won’t — and can’t — understand the term logocentrism. In fact a potential reader would need to make a leap of faith into Derrida in order to discover the ̶t̶r̶u̶t̶h̶ about logocentrism — and indeed the ̶t̶r̶u̶t̶h̶ about deconstruction generally.

Derrida might also even have said (if in a roundabout way) that his words above were expressed (or even designed) to fail in every respect… or not to fail in every respect… or to do both… or to do all three… or to read intertexts on a transcendental infinite of quantum Otherness.

So where to begin?

What about truth?

Derrida — in the passage above — was also saying (outrightly!) that something is “false”. (Derrida used the words “they are at least false”.) So surely Derrida must have believed in truth in order to say that something is false.

So we can also ask if it true that the the third person present indicative is S is P? Yet Derrida would never have plainly and clearly said, “I believe in truth” or even anything like that.

It can also be asked exactly why it is that “All sentences of the type ‘Deconstruction is X’” manage to “miss the point”? Is it because they’re false? Is it because there is, in actual fact, something true — or even semantically determinate — about what deconstruction is? Or was Derrida just using words in any way he wished (i.e., playing with the sign or signifier) — perhaps for political, career, literary and/or emotional reasons?

Yet Derrida himself did believe in truth! And he — if only rarely — said so.

Take the following passage (in response to John Searle) from Limited Inc (1988) in which Derrida was explicit as could be:

“[H]ow can he discuss, and discuss the reading of what he writes? The answer is simple, this definition of the deconstructionist is false (that’s right: false, not true) and feeble: it supposes a bad (that’s right: bad, not good) and feeble reading of numerous texts, first of all mind, which therefore must be read or re-read.”

The thing here is that it took the American philosopher John Searle’s criticisms to drag a commitment to truth out of Derrida. And by selectively endorsing the notion of truth in this particular instance, this too can be seen as typical Derridean gameplaying and/or one-upmanship. And that’s because in large amounts of Derrida’s other work he explicitly carried out the deconstruction of the concept [truth] — and, indeed, of all other logocentric concepts.

The thing is, then, that Derrida did and he didn’t believe in truth.

He believed in truth in order to win one philosophical game and rejected it in order to win another.

The other way of putting this is that Derrida did believe in truth when it came to defending very particular political and philosophical causes and ideas. However, he didn’t believe in truth when he was attacking other very particular political and philosophical causes and ideas.

So what about Derrida with his other face on?

In the following Derrida speaks of his embrace “of the play of the world” in which we have

“a world of signs without fault, without truth, and without origin which is offered to an active interpretation”.

This is much more literary and flamboyant that his clear and sarcastic riposte to John Searle above. And that was often the case with Derrida. Specifically, when explicitly accepting truth (or Justice), he was (fairly) clear and explicit. However, when rejecting truth, he was usually obscure, pretentious and/or implicit.

And, of course, it was the case that Derrida also shoehorned in his own technical terms (or neologisms) into these debates. And that enabled him to slither around a little. That is, he might have argued that the word “truth” — as used by himself — was put “under eraser” (sous rature) … Except that the word “truth” wasn’t put under eraser in the passage (against Searle) above.

At least Derrida didn’t refrain from using the logocentric word “false”. Of course Derrida would have had an easy reason for this in that he often admitted that he — and others — couldn’t escape from “Western metaphysics”. For example, in his ‘Structure, sign and play in the discourse of the human sciences’ (1966/1970), he wrote the following words:

“There is no sense in doing without the concepts of metaphysics in order to shake metaphysics. We have no language — no syntax and no lexicon — which is foreign to this history; we can pronounce not a single destructive proposition which has not [been contaminated]…”

So Derrida stated what the third person indicative is and therefore made an explicit commitment to at least some level of semantic — and even ontological — determinacy. And all this within his broader deconstructive context of a stance against ontological rigidity and semantic determinacy.

Now what about these words from the opening passage?-

“One of the principle things in deconstruction is the delimiting of ontology [].”

What reasons did Derrida — or anyone else — have for wanting to “delimit[] ontology”? Were they moral reasons? Political reasons? Reasons of Derrida’s highly-successful career and/or of his strong commitment to philosophical one-upmanship? Would any of his reasons for delimiting ontology have been based on ontological positions, values or beliefs which were themselves unlimited or undeconstructible? (In Derrida’s own case, consider his stance on platonic Justice. See ‘Derrida on Justice: The à-venir and the Undeconstructible’.)

Elsewhere and in response to a question from Toshihiko Izutsu about the meaning (or definition) of “deconstruction”, Derrida said that the question “What is deconstruction?” is problematic because it should be a question of “what deconstruction is not, or rather ought not to be”. Derrida also stated that “[d]econstruction is not a method, and cannot be transformed into one”. Furthermore, Derrida also told his readers that deconstruction isn’t a kind of analysis or a critique (see here).

Of course because Derrida and his followers attempted to have their cakes and eat them too, they wouldn’t have ever argued that there is literally no method, analysis or critique, etc. in deconstruction. So it can be argued that they simply didn’t like the terms “method”, “analysis” or “critique” because those words would have tied them too closely to the Platonic/Western Tradition. That said, it’s no surprise that Derrida also stated that there was “the necessity of returning to them, at least under erasure”. Yet the logic of these denials and negations hardly makes sense. It simply doesn’t follow that when there’s a definition of deconstruction, then that definition would be an attempt to make the concept [deconstruction] immune to deconstruction — or even immune to plain criticism/analysis.

Gayatri Spivak and Christopher Norris on What Deconstruction Isn’t

Even philosophers and theorists who were sympathetic to Derrida have been keen to know what deconstruction is - despite all the claims that it isn’t… anything. (Or that it is and it isn’t something… or neither… or… or…)

Take the case of the Indian literary theorist and feminist critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1942-).

At one point Spivak wanted (or desired) deconstruction to be something. Thus she wrote the following words:

“For a time I felt ferociously angry with deconstruction because Derrida seemed not to be enough of a Marxist. He also seemed to be a sexist. But that’s because I was wanting deconstruction to be what it isn’t. I’ve realized its limits — by not asking it to do everything for me… I have little patience with people who are so deeply into deconstruction that they have nothing else substantive to think about.”

In order to have believed that Derrida wasn’t “enough of a Marxist”, then that must have meant that Spivak also believed that Derrida was — at least to some extent — a Marxist. (How did she quantify this?)

In addition, in order for Spivak to have said that she “want[ed] deconstruction to be what it isn’t”, then surely she must have come to know (or at least believed she came to know) what deconstruction is. That is, if Spivak didn’t know what deconstruction is (at least in some sense), then how did Spivak come to know that it wasn’t Marxist enough for her? What exactly made deconstruction not Marxist enough for Spivak? It must have been something about what deconstruction is.

Similarly, Spivak must have known what deconstruction is in order to have “realized its limits”. In other words, any given x (which has “limits”) must also have boundaries of some kind. And in order to recognise the boundaries of that x, one must also know — at least to some extent — what that x is. Thus, in Spivak’s case, she must have known (or simply believed she knew) what deconstruction is.

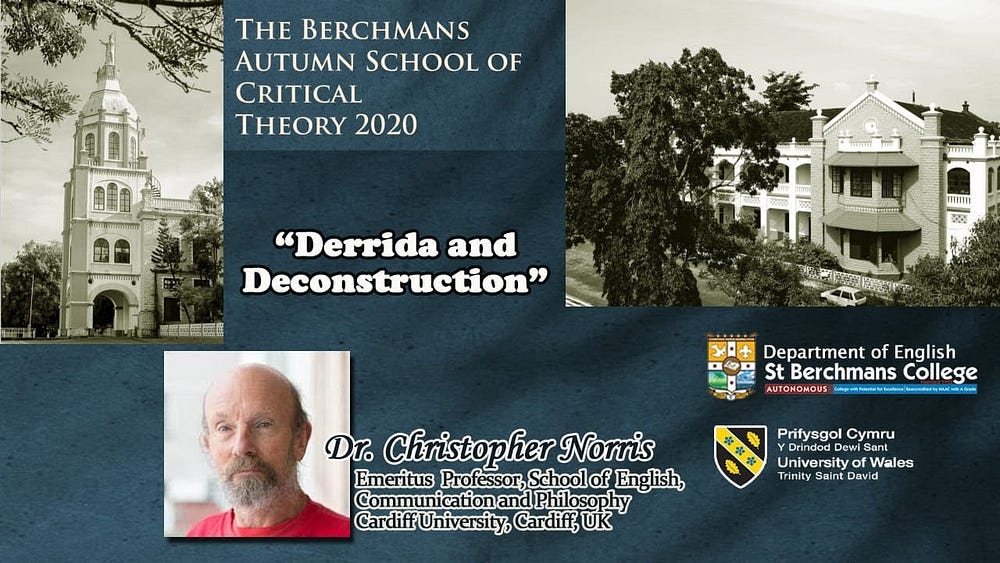

Now let’s take a look at Christopher Norris.

The following passage is philosopher and literary critic Christopher Norris (1947-) telling us what deconstruction isn’t:

“The point will bear repeating: deconstruction is not simply a strategic reversal of categories which otherwise remain distinct and unaffected. It seeks to undo both a given order of priorities and the very system of conceptual opposition that makes that order possible.”

As in the case of Gayatri Spivak, in order for Norris to have told us what deconstruction isn’t, he must have known what deconstruction is — at least to some extent. More concretely, if deconstruction

“is not simply a strategic reversal of categories which otherwise remain distinct and unaffected”

then that must be because deconstruction is something other than that reversal of categories.

Norris continued:

“Thus Derrida is emphatically not trying to prove that ‘writing’ in its normal, restricted sense is somehow more basic than speech. On the contrary, he agrees with Saussure that linguistics had better not yield uncritically to the ‘prestige’ that written texts have traditionally enjoyed in Western culture.”

So, in this instance at least, Norris rejected what’s often called the “binary opposition” of writing/speech (see Derrida’s arche-writing). And that must surely mean the following:

Deconstruction is the rejection of binary oppositions.

Isn’t that what Norris is explicitly saying?

So deconstruction is… something?

Of course there are many other examples of Derrida and other deconstructors telling us what deconstruction isn’t.

For example, it’s said that deconstruction isn’t a “project” either. Yet if deconstruction had no project at all, then why would Derrida — or any other deconstructor — have ever written a single syllable? Indeed it can also be added here that the position of having no project is still a project — i.e., the project of not having a project.

Simon Critchley & Others on What Deconstruction Is

There are many negative definitions (or accounts) of what deconstruction is. Take these examples:

“the latest fashion in literary theory”, “an ancient error of scepticism and irrationalism”, “a repetition of dead-end themes in German idealism”, “a dangerous neo-Heideggerianism”, “a needless and frivolous hermeticism”, etc.

But let’s concentrate here on some positive accounts (or definitions) of what deconstruction is.

Take the following words from Professor Simon Critchley (1960-). (These words aren’t actually expressed as a definition.) Critchley writes:

“[T]his relation to tradition [as displayed by continental philosophy] is not some conservative acquiescence in the face of the past, but rather takes the form of a critical confrontation with the history of philosophy, what Heidegger calls Destruktion or Abbau, words that Derrida renders into French as déconstruction. It is a question here of a critical dismantling of the tradition in terms of what has been unthought within it and what remains to be thought.”

(This mention of “the past” by Critchley is a reference to most — or even all — analytic philosophers ignoring the history of philosophy.)

This is one definition of what deconstruction is that’s surely essential (in a non-ontological sense, of course) and wide-ranging. It’s also very helpful in that it tells us how the word “deconstruction” was born.

So to express Critchley’s words as a example of Derrida’s S is P. We have this:

Deconstruction is a critical confrontation with the history of philosophy.

Of course no one would argue that deconstruction could be entirely summed up by the single sentence, “Deconstruction is a critical confrontation with the history of philosophy.” (Or, for that matter, with this sentence: “Deconstruction opposes all binary oppositions.”) Yet we can still say, “Deconstruction is X” … or Y, or Z, etc. Thus not being able to sum deconstruction up in a single S is P puts it in exactly the same position as every other philosophical ism!

So why did Derrida and other deconstructors have such a big problem with statements like “Deconstruction is…”?

Yet some deconstructors (i.e., other than the ones mentioned in this essay) have also told us exactly what deconstruction is.

For example, the following are some (seemingly) positive definitions of what deconstruction is: “an ethical response to complacency”, “literature’s revenge on philosophy”, “not what you think”, “a positive device for making trouble”, “a way of reading theoretical texts”, “a way of doing philosophy”; and, more relevantly to this essay, “resistance to questions which begin ‘What is…?’”.

Of course Derrida himself would no doubt have rejected all those positive accounts of deconstruction… as he also rejected all the negative ones too.

Yet would those rejections be any different from, say, Ludwig Wittgenstein rejecting most — or even all — of the interpretations of his work (as he almost did)? Or any different from scholars (or experts) getting hot under the collar when their favourite philosophers (or theorists) are encroached upon by someone seemingly less expert (or in the know) than they believe they are?

Thus Derrida has simply suffered — when it comes to the supposed “misreadings” of what deconstruction is — the same fate as all other philosophers. (Derrida once said: “All our readings are misreadings.”) But, because of Derrida’s bizarre prose style and his relentless game-playing, the situation has often been far worse than most of the other cases which can be cited.

No comments:

Post a Comment