This is a response to Sabine Hossenfelder’s article, ‘Electrons Don’t Think’.

Sabine Hossenfelder (that link is to her Medium account) is a physicist and a Research Fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies. She’s also a popular writer on science and a presenter.

As for her article itself: it’s crude and rhetorical. My piece is also (somewhat) rhetorical. It is so because I believe that my own unacademic phrases are a fitting response to Hossenfelder’s own.

But first things first.

I’m not a panpsychist.

I’m not even particularly sympathetic to panpsychism and find some panpsychists’ ideas absurd. Nonetheless, none of this warrants Hossenfelder’s philosophically ignorant and sarcastic article on panpsychism. Indeed her article is so cheap that she refers to the papers and books of panpsychists as “pamphlets”.

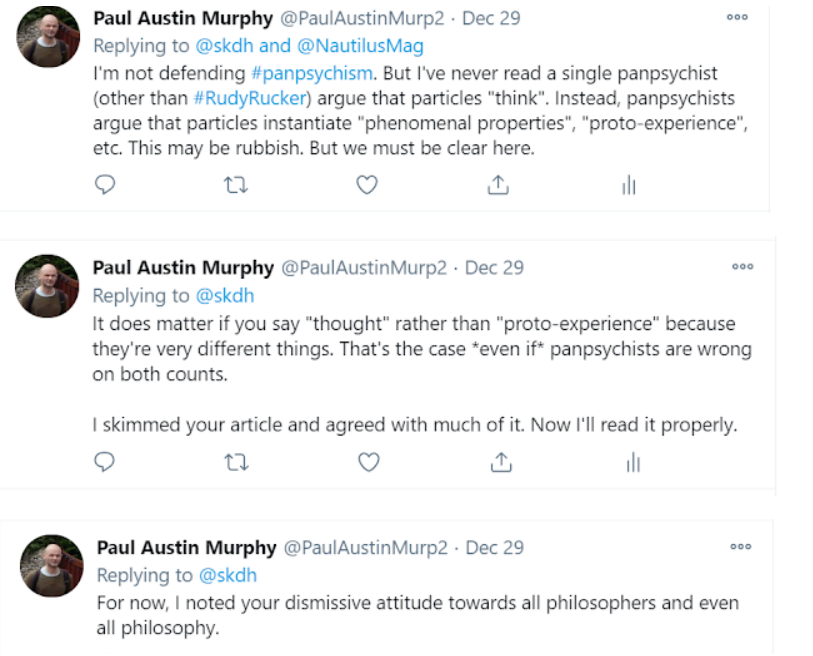

This is when I must freely confess that this piece is a least partly personal. What I mean by this is that Hossenfelder blocked me on Twitter for offering two very-mild criticisms (see screenshots below) of her article on panpsychism. I say partly personal because I’d obviously already offered criticisms of her article before she blocked me. In other words, this piece isn’t a long bitching session written in response to being blocked on Twitter.

In any case, it seems that not only is Hossenfelder critical of all philosophers (see later), she isn’t even prepared to debate philosophical issues either. I presume that this is because she deems such a thing to be a waste of her precious time.

Oddly enough, Hossenfelder has attempted to foresee such criticisms of her dismissive attitude toward philosophy; and that’s why she wrote these words:

“Now, look, I know that physicists have a reputation of being narrow-minded.”

Now simply because, say, a serial liar (or sadist) mentions that the fact that other people take him to be a serial liar (or sadist), that doesn’t mean that he isn’t a serial liar (or a sadist). In other words, Hossenfelder’s article, her attitude to (all) philosophers, and her blocking critics shows that she is indeed narrow-minded — at least when it come to panpsychism and philosophy generally.

Still, let Hossenfelder explain why she’s narrow-minded. She continues:

“But the reason we have this reputation is that we tried the crazy shit long ago and just found it doesn’t work. You call it ‘narrow-minded,’ we call it ‘science.’ We have moved on.”

So why is Hossenfelder using the royal “we” here?

And what does “we tried the crazy shit long ago” even mean?

How does physics “try” panpsychism or any other philosophical theory?

Hossenfelder should know that many physicists — unlike herself — have not been dismissive and smug about philosophy. This is true of the some of the greatest names of 20th-century physics. These names include such people as Albert Einstein, Erwin Schrodinger, Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, Max Born, John Wheeler, Freeman Dyson, etc. (See Lee Smolin’s ‘Physics Needs Philosophy’. (Arguably this wasn’t true of Paul Dirac, Richard Feynman, etc.) Indeed various contemporary physicists are still very much indebted to — and respectful of — philosophy. These physicists include Roger Penrose, Lee Smolin, Carlo Rovelli, Sean Carroll, Paul Davies, Leonard Susskind, Martin Rees, Max Tegmark, David Deutsche, etc.

It can even be argued that the greatness of these physicists was — and is — at least partly a result of their being philosophical; as well as their being knowledgeable about philosophy. Hossenfelder, on the other hand, is a very-minor physicist who’s known for her “popular-science” books and broadcasts. She will, however, be known to a few physicists within her narrow field/s — not only for her popular science. (She also has the appealing selling point of being very “quirky”.)

Hossenfelder’s Discovers that Philosophers Have Produced “Pamphlets” on Panpsychism

In the introduction I mentioned that Sabine Hossenfelder rather cheaply referred to the papers and books of panpsychists as “pamphlets”.

Hossenfelder doesn’t seem to have read any panpsychists. What’s more, she more or less admitted this when she wrote this line:

“I mean I discovered there’s a bunch of philosophers who produce pamphlets about [panpsychism].”So Hossenfelder didn’t “discover[]” the words and arguments of this “bunch of philosophers”. She discovered that they had “produced pamphlets” about panpsychism. In other words, the very realisation that pamphlets on panpsychism had been published motivated Hossenfelder to write her article. (That may well mean she got all her information on panpsychism from Wikipedia; or, perhaps, from a mate at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies.)

The other terrible thing about Hossenfelder’s article (after her dismissal of all philosophers at the end of her piece) is that she doesn’t quote a single panpsychist. Indeed she doesn’t even paraphrase a single panpsychist or tackle a single argument in favour of panpsychism.

So if Hossenfelder believes that philosophy is such a waste of time (which must explain why she blocks people who ask philosophical questions), then why write this article at all? Why supply extra oxygen to panpsychists? Why waste other people’s time if she doesn’t like her own time being wasted?

The Word “Consciousness” isn’t a Synonym of “Thought”

Sabine Hossenfelder defines panpsychism in the following way:

“It’s the idea that all matter — animate or inanimate — is conscious, we just happen to be somewhat more conscious than carrots. Panpsychism is the modern élan vital.”Not all panpsychists would fully endorse that definition. And Hossenfelder would have realised that had she bothered to read a single paper by a single panpsychist.

Various panpsychists don’t argue that electrons are conscious in the way that human beings are conscious. (They certainly don’t argue that they “think”.) Such panpsychists argue that they particles instantiate “phenomenal properties”, “proto-experience”, “micro-experience”, “panproto-properties”, etc. Sure; these may be problematic positions too. However, Hossenfelder simply ignoring them is intellectually gross.

Hossenfelder also conflates consciousness with thought. She goes on to write:

“Now, if you want a particle to be conscious, your minimum expectation should be that the particle can change. It’s hard to have an inner life with only one thought. But if electrons could have thoughts, we’d long have seen this in particle collisions because it would change the number of particles produced in collisions.”

I’m not even sure if I understand the first two sentences above. That is, we have this sentence

“It’s hard to have an inner life with only one thought.”

following from this one:

“Now, if you want a particle to be conscious, your minimum expectation should be that the particle can change.”

It’s true that some panpsychists have used phrases like “inner life”. But Hossenfelder doesn’t say what she means or what she believes panpsychists mean by those two words. And, as stated, it’s not a phrase that all panpsychists would be happy with.

Again, all this seems to be a result of Hossenfelder conflating consciousness with thought. And that’s precisely what many panpsychists don’t do. (Something she didn’t even want to acknowledge in my mild criticisms— see the tweets above.) Most panpsychists don’t claim that particles think or even that thermostats think. (See my David Chalmers’ Thermostat and its Experiences’.) They claim that particles instantiate “phenomenal properties”, “proto-experience”, etc. These positions, of course, need to be fleshed out. However, Hossenfelder doesn’t even acknowledge them.

Talk of “phenomenal properties”, etc. shouldn’t be hard to understand even in the case of human beings. There are many states of consciousness which don’t involve thought; such as the feeling of a specific pain, an orgasm, a trancelike state, etc. Sure, thoughts may accompany these phenomenal states; though they don’t necessarily do so.

And it’s not clear why Hossenfelder is emphasising “change” either.

She seems to be saying that a given particle has very limited properties in and of itself. However, particles do change in that they move and they interact with other particles, forces, charges, etc. So taking particles in and of themselves doesn’t really make sense. Each particle is part of a system (or of many systems). As ontic structural realists put it: particles aren’t “individuals” or even things.

This is how the philosophers James Ladyman and Don Ross put this position as it relates to quantum entanglement:

“[Q]uantum particles appear sometimes to possess all the same intrinsic and extrinsic properties. If two electrons really are two distinct individuals, and it is true that they share all the same properties, then it seems that there must be some principle of individuation that transcends everything that can be expressed by the formalism in virtue of which they are individuals.”

Ladyman and Ross also take the example of fermions generally. They make the point that

“that fermions are not self-subsistent because they are the individuals that they are only given the relations that obtain among them”.

What’s more, “[t]here is nothing to ground their individuality other than the relations into which they enter”. And, according to Ladyman and Ross, even Albert Einstein once claimed that particles don’t have their own “being thus”.

Having said all that, taking particles as parts of systems problematises the issue for panpsychists too in that the whole system — not individual particles — may need to be taken as being conscious or having phenomenal properties.

If we get back to Hossenfelder’s rejection of consciousness when it comes to particles.

Hossenfelder concludes by saying that “electrons aren’t conscious, and neither are any other particles”. She rounds that off by adding: “[i]t’s incompatible with data”. Yet animals and even humans being conscious can be seen as being “incompatible with the data” too — as behaviourists, neuroscientists and numerous philosophers have argued over the decades. Or, at the least, the behaviour (including speech and other sounds) of animals and humans can be explained without positing consciousness. In a crude behaviourist sense, then, all we have is behaviour. Yet we also have “behaviour” (or at least movement and interaction) with particles too.

Complexity and the Combination Problem

Hossenfelder does at least note the possibility of the “intrinsic nature” (or, as she puts it, “internal states”) of particles. That is, it may not all be about quantum numbers, position, momentum, relations, interactions, etc. So what do philosophers say about intrinsic nature?

Take the Australian philosopher David Chalmers, who writes:

“[I]t is often noted that physics characterizes its basic entities only extrinsically, in terms of their relations to other entities, which are themselves characterized extrinsically, and so on.”

Basically, this shows us how physics ignores intrinsic nature. But, still, what is intrinsic nature? (Don’t tell us what it isn’t.)

So what does the physicist Lee Smolin have to say? This:

“Perhaps everything has external and internal aspects. The external properties are those that science can capture and describe through interactions, in terms of relationships. The internal aspect is the intrinsic essence; it is the reality that is not expressible in the language of interactions and relations.”

Yes; Smolin still isn’t telling us what intrinsic nature is — he’s telling us what it isn’t. And this is a problem.

We can say, then, that intrinsic properties are effectively like Immanuel Kant’s own noumena. That is, they are things which we cannot say anything about (as Smolin and Chalmers have indirectly shown us). This doesn’t mean that noumena and intrinsic properties are exactly the same thing in every respect. (Kant said lots of things about that which we cannot speak.) However, the fact that it seems almost impossible to say anything concrete about intrinsic properties makes them very much like Kant’s noumena.

Now lets get back to Sabine Hossenfelder. She writes:

“With the third option it is indeed possible to add internal states to elementary particles.”

The problem (if it is a problem) here is that these additional internal states may themselves be defined purely by numbers, relations, structures, interactions and whatnot. That is, additional internal states (at least as defined by Hossenfelder) may not — or will not — give us intrinsic properties.

Hossenfelder is also arguing that at least some level of complexity must be relevant when it comes to a particle’s consciousness (or “thought”, as she also puts it).

She then seems to hint at panpsychism’s “combination problem” with the following words:

“But if your goal is to give consciousness to those particles so that we can inherit it from them, strongly bound composites do not help you.”

Yet Hossenfelder is implicitly acknowledging two very different problems above. Namely:

(1) The question as to whether or not particles are conscious.

And the combination problem; which can be stated in the following way:

(2) What is the precise relation between the conscious properties of particles and the consciousness brought about by a human brain (which is ultimately made up of particles) and which is experienced by a subject (or by a being)?

To use Hossenfelder’s own phrase: how can “we [] inherit” our own consciousnesses from the consciousnesses of billions of tiny particles? In other words, how do we make sense of “strongly bound composites” (i.e., brains which are conscious) and the particles (which are also thought to be conscious by panpsychists) which make up those composites?

That is certainly a problem.

Numbers and Hossenfelder’s Pythagoreanism

Sabine Hossenfelder — admittedly like many physicists — seems to conflate the numbers used to describe physical phenomena with physical phenomena. More specifically, she sees quantum numbers themselves as what she calls “properties”. She writes:

“The particles in the standard model are classified by their properties, which are collectively called ‘quantum numbers’.”

In terms of detail:

“The electron, for example, has an electric charge of -1 and it can have a spin of +1/2 or -1/2.”

Now the above refers to the particles of the Standard Model being classified by quantum numbers. These numbers are also deemed to “properties. In other words, numbers are taken to be the actual properties of particles.

An alternative approach to all this is to state these three positions:

1) Numbers are applied to physical phenomena.2) Numbers are used to describe physical phenomena.

3) Number don’t constitute physical phenomenon.

More specifically, numbers aren’t the properties of particles. That is, the numbers -1, +1/2 and -1/2 aren’t properties. Electric charge is a property of a particle. And that charge is measured — in Hossenfelder’s example — by the numbers -1, +1/2 and -1/2.

So perhaps Hossenfelder is a Pythagorean!

Pythagoreans believe that numbers themselves are the literal properties of things. Or, more radically, “all things are numbers”. Thus each particle is literally a set of numbers; which, on Hossenfelder’s reading, are also taken to be properties. (Contemporary ontic structural realists see themselves as Pythagoreans — see here!.)

Alternatively, Hossenfelder may be a Platonist in that even though numbers are abstract and non- spatiotemporal, they can still be seen as the properties of particles.

Of course this is a complex philosophical issue and physicists may also have good instrumentalist or anti-realist reasons for conflating (if it is conflating) physical phenomena with the numbers used to describe them — especially when it comes to quantum physics! But these would be philosophical reasons.

So take the science writer and journalist John Horgan’s position as expressed in the following passage:

“[M]athematics helps physicists definite what is otherwise undefinable. A quark is a purely mathematical construct. It has no meaning apart from its mathematical definition. The properties of quarks — charm, colour, strangeness — are mathematical properties that have no analogue in the macroscopic world we inhabit.”

Horgan is basically arguing that without the mathematics, we’d have almost (or literally) nothing to say about the quantum world — real or otherwise. When it comes to the quantum world, the usual means of (as it were) ownership aren’t available to us. That is, we can’t observe, feel, smell or (often) even imagine the quantum world. Thus the maths is all we’ve got.

Alternatively, take Max Tegmark’s words:

“‘ [If] [t]his electricity-field strength here in physical space corresponds to this number in the mathematical structure for example, then our external physical reality meets the definition of being a mathematical structure — indeed, that same mathematical structure.”

The problem for Hossenfelder is that these are philosophical positions. They aren’t positions within physics. And they’re stated by people who have no problem with the obvious situation : that physics can’t exist without philosophical positions and - more relevantly - philosophical presuppositions.

And Yet Hossenfelder believes that she doesn’t philosophise and that philosophy is a waste of time.

Run Away From Philosophers!

The last line in Hossenfelder’s ‘Electrons Don’t Think’ is the worst of all. Here it is:

“Summary: If a philosopher starts speaking about elementary particles, run.”

Clearly, she has all philosophers in mind here. In other words, not only philosophers who also happen to be panpsychists. And that must include the many philosophers who have degrees in physics and mathematics. Then we have the many well-known physicists who respected philosophy and philosophers and even happily admitted that there were philosophical elements embedded in their own theories.

In any case, it’s not as if philosophers are attempting to add to the physics of particles. And they’re not attempting to adapt or to change the Standard Model (as Hossenfelder herself is attempting to do). Philosophers aren’t offering better equations, better tests or new definitions of the word “electron”. And, as far as I know, no philosopher has ever claimed to discover a new particle.

So philosophers aren’t physicists. And they certainly don’t claim to be physicists. All this means that philosophers don’t deal with evidence in the same way in which physicists do.

Like all physicists, then, Hossenfelder stresses the importance of evidence. Thus it’s no surprise that she demands evidence for panpsychism. She writes:

“How do these philosophers address the conflict with evidence? Simple: They don’t.”

More specifically, she continues:

“Can elementary particles be conscious? No, they can’t. It’s in conflict with evidence.”

What would evidence for panpsychism look like?

Panpsychists have freely admitted that evidence isn’t a germane notion for panpsychism — or, indeed, for any metaphysical theory. Instead, philosophers theorise or make sense of what scientists and laypersons take to be evidence. Philosophical positions themselves don’t have evidence in any scientific sense. Now of course this situation is very problematic. And that’s precisely why metaphysics has come in for a lot of criticism from scientists — and even from philosophers themselves! (For example, from the logical positivists, Ludwig Wittgenstein, ontic structural realists, etc.)

This means that, in a strong sense, much of what is true of panpsychism is also true of all metaphysical theories. So perhaps that explains why Hossenfelder rejects all philosophers and all philosophy. Again, philosophers aren’t physicists. What’s more, philosophers don’t claim to be physicists.

So, to sum up, Sabine Hossenfelder’s basic problem is that she simply doesn’t like the fact that philosophy isn’t physics. Yes; she can’t bring herself to accept that an apple isn’t an orange.

No comments:

Post a Comment