I came across the following incredible — almost surreal — passage written by a (London) Times correspondent who was writing in the 1930s. (It’s quoted in Andrew Hodge’s brilliant book Alan Turing: The Enigma.) The passage goes:

“A number of mathematicians met recently at Berlin University to consider the place of their science in the Third Reich. It was stated that German mathematics would remain those of the ‘Faustian man’, that logic alone was no sufficient basis for them, and that the German intuition which had produced the concepts of infinity was superior to the logical equipment which the French and Italians had brought to bear on the subject. Mathematics was a heroic science which reduced chaos to order. National Socialism had the same task and demanded the same qualities. So the ‘spiritual connexion’ between them and the New Order was established — by a mixture of logic and intuition [].”

I’ll comment in detail on this passage later. However, the first thing it brought to mind was the English philosopher Philip Goff and his political interpretations of recent experiments on plants.

Philip Goff & Pascual Jordan on the Politics of Plants

Professor Philip Goff offers us political and philosophical (i.e., panpsychist) interpretations of the experiments and research on plants carried out by the ecologists Professor Monica Gagliano and Professor Suzanne Simard. He makes all sorts of political claims about plants which just so happen to perfectly square with his own (prior) politics.

And that’s what the Nazis did with mathematics in the 1930s (at least according to the passage above), what the Radical Science Movement did in the 1960s/70s and what various activists are doing today.

Take Goff again. He says (of Suzanne Simard’s research) that

“[t]he mycorrhiza structures allow for a complex system of egalitarian redistribution”.

And, elsewhere, Goff writes:

“[H]uman societies social harmony is possible only when they are united by strong ties of kinship. No such prejudice exists among trees. Even across species there exist networks of reciprocal support. In summer, the birch trees help out the fir trees by passing along carbon, especially to the fir trees that are shaded from the sun. In winter, there is reciprocation: when the birches are leafless, the firs provide much needed carbon support.”

Of course the words “egalitarian redistribution” are taken from the human political domain. Indeed Goff himself — coincidentally enough — is strongly in favour of egalitarian redistribution in the human world and has written about it in newspapers and in his own blog. (See Goff’s article ‘Our Glastonbury U2 protest was a call for an ethical tax’, written for the Guardian newspaper.)

It’s worth mentioning here the well-known theory that exactly the same data, evidence or experiment about — or on — x (in this case plants) can be used as ammunition to advance just about any political position. (See underdetermination of theory by data/evidence.) Indeed, historically, this has often been done. (Think about how some 19th-century Darwinists and 20th-century fascists relied on the animal world to advance their politics — see later sections.) More specifically, Goff’s own talk of “quid pro quo relationship[s]” in the plant world could even be used to advance political positions which are diametrically opposed to his own.

This basic distinction between theory/experiment/data and interpretation goes all the way down to, for example, the distinction between the mathematical formalism/s of quantum mechanics and their interpretations.

So now let’s compare Goff’s words to the words of German physicist and Nazi (at least at this time) Pascual Jordan.

Pascual Jordan (1902–1980) at one point interpreted biology through a Nazi lens. Take this passage:

“We know that there are in a bacterium, among the enormous number of molecules constituting this … creature … a very small number of special molecules endowed with dictatorial authority over the total organism; they form a Steuerungszentrum [steering centre] of the living cell. Absorption of a light quantum anywhere outside of this Steuerungszentrum can kill the cell just as little as a great nation can be annihilated by the killing of a single soldier. But absorption of a light quantum in the Steuerungszentrum of the cell can bring the entire organism to death and dissolution — similar to the way a successfully executed assault against a leading [führenden] statesman can set an entire nature into a profound process of dissolution.”

Is the above any different to interpreting plant behaviour through a leftwing lens?

(See also Soviet/communist Lysenkoism here and Stephen J. Gould later.)

German Mathematics?

If someone is extremely politically committed to a specific ideology or political movement, and is a diligent activist, then he/she may well interpret almost everything politically. (This is similar to what happens with religious fundamentalists.) And, of course, that everything will include science.

So it’s no surprise that the German National Socialists of the 1930s did this.

Just as recent activists and political theorists have classed maths as “white supremacist” (see here), so the Nazis believed that “German mathematics would remain those of the Faustian man” and suchlike. The Nazis wanted a Germanic maths; just as some activists today want maths to serve cotemporary political projects. But of course maths can be neither Germanic nor ideologically correct. Of course it can be pushed or interpreted in such ways — but it makes little sense to that maths itself is.

The passage above (from the 1930s Times) tells us that

“logic alone was no sufficient basis for them, and that the German intuition which had produced the concepts of infinity was superior to the logical equipment which the French and Italians had brought to bear on the subject”.

This contains some well-rehearsed points and distinctions in the philosophy of mathematics or in metamathematics.

For example, there was once a long-running debate as to whether maths is a part of logic or logic is a part of maths (see here). It just so happens that these Nazi mathematicians believed — in broad terms — that French and Italian mathematicians had focused on the logic of maths and their fellow Germans had focussed on intuition (see here). Indeed, culturally and historically, these 1930s Nazis might well have been correct. That is, perhaps the Italians and French did focus on the logic of maths and not on (Germanic) intuition at that time.

These German Nazi mathematicians can be criticised from a realist/Platonic angle too. (What nationality takes a specifically realist view on maths?) That is, a realist/Platonist would never argue that any nation could “produce the concepts of infinity”. People can only gain access (say, via “direct insight” or intuition) to infinity and then make use it. To realists and to many others, infinity isn’t created — it is discovered. Sure, the concept (or concepts) of infinity isn’t the same as infinity itself. But it’s still the case that its not a very realist/Platonic position to stress the production of the concepts of infinity.

That said, perhaps mathematical realism is actually a national phenomenon. So what about anti-realism?

And do the “concepts of infinity” serve right-wing or left-wing politics?

These German mathematicians also said that maths is a “heroic science which reduced chaos to order”. Is that statement any more or less political than the poststructuralists, etc. who’ve argued against the “mathematising of experience” or “the urge to reduce society to mathematics”? (Arguably, though, these are positions against the applications of mathematics, not mathematics itself.) Indeed many contemporary theorists have themselves stressed this negative aspect of maths — how mathematicians attempt to order everything. Then again, New Agers, mystics and “spiritualists” (who would deem themselves to be miles away from the Nazis) have also emphasised “intuition” against “cold logic” and “reductionism”. Indeed these Nazi mathematicians themselves used the words “spiritual connexion” to refer to what they were doing. Yes; Nazi spiritualism was quite a big thing at one point.

Now Take the case of Stephen J. Gould.

Stephen Jay Gould on Evolutionary Progress

American palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist Stephen J. Gould pointed out that various scientists had put “right-wing”, “racist”, “capitalist”, and even “fascist” slants on various evolutionary and biological data.

And what did Gould do in response?

He often put a Leftist/Marxist slant on evolutionary and biological data.

Take Gould’s case against evolutionary “progress”. This was infused by his leftwing politics. But that’s not a surprise because he was a self-described “Marxist” (see here) who was part of the Radical Science Movement.

Gould’s position is so overladen with political (as it were) concern and Marxist theory that he treated many of his opponents as no less than straw targets. Basically, Gould believed that any belief in evolutionary progress is always politically dangerous — and that position infused many of his arguments. (Many other commentators — both positive and negative — have connected Gould’s views on punctuated equilibrium to his Marxism too— see here.)

Take this highly political and rhetorical passage from Gould:

“[E]volution has been saddled with a suite of concepts and meanings that represent long-standing Western social prejudices and psychological hopes, rather than any account of nature’s factuality.”

More relevantly, Gould concluded:

“Most pernicious and constraining among these prejudices is the concept of progress [].”

Many have said — in defence of Gould — that “facts are facts” and it simply doesn’t matter about his politics. True; but Gould’s political glosses or interpretations of those facts (as with those quotes just given) are not themselves (scientific) facts. (Ironically, those sympathetic to Gould have also freely admitted that his politics influenced his science; but, of course, in an entirely positive way — see here from www.marxists.org.)

The other problem here is that hardly any — if any — contemporary biologists or evolutionary theorists believe that evolution has an “inherent drive” (whatever that is!) towards “progress”. (They might have done on the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century.) And they don’t do so because it’s almost impossible to see evolution is such a personified or reified way. That is, evolution can’t be seen as a single abstract entity or as a single whole. Thus evolution can’t go in any single direction — either toward progress or toward simplification (or even toward stasis).

So it’s not as if there is a single biologist or evolutionary theorist who isn’t fully aware of the many species that haven’t “progressed” at all in millions of years (e.g., crocodiles, velvet worms, cow sharks, lice, horseshoe crabs, cockroaches, etc.). Such biologists and theorists are also aware that evolution can move in the direction (which is a kind of personification itself) of simplification — as with certain kinds of parasites .

But why do these widely-accepted facts rule out progress for some species in some situations and in some respects? Of course the word “progress” is loaded and needs to be defined. However, the problem is that Gould took the word “progress” in a entirely political way and then he simply assumed that other biologists and evolutionary theorists were using that word in his own political way too. (This was a kind of psychological projection on Gould’s part.)

So take Richard Dawkins.

Dawkins — who Gould often attacked and vice versa (see here) — argued that there is a

“tendency for lineages to improve cumulatively their adaptive fit to their particular way of life, by increasing the numbers of features which combine together in adaptive complexes”.

More relevantly, Dawkins concluded:

“By this definition, adaptive evolution is not just incidentally progressive, it is deeply, dyed-in-the-wool, indispensably progressive.”

Ironically, Dawkins agreed with the broad gist of Gould’s argument on evolutionary progress. However, he simply saw exceptions to — and qualifications of — it. In other words, Gould’s political stance against progress in evolution turned out to be as simplistic and generalised as the the positions (many not actually held by any professional biologists) he was against.

Of course if someone says that Gould’s position is essentially political, then someone else may say that Dawkins’s own counter-position is political too. Except that Gould actually admitted that politics infused all his science (see here). Dawkins, on the other hand, never made any explicit connections, is not a “fascist” or “racist” (though many on the Far/Marxist Left believe he is) and is in fact a political liberal, anti-racist, etc. Of course these facts about Dawkins’ politics obviously don’t automatically stop his position on evolutionary progress from being political in some way.

Science for the People

It’s often the case that some of those who speak out against the political nature of science don’t do so because they believe that science should be apolitical: they do so because they believe that science should be political in the correct ways.

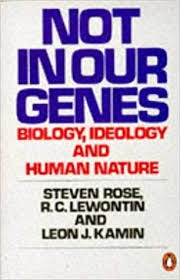

Take Science for the People and the Sociobiology Study Group in the 1970s and 1980s. Stephen Jay Gould — again — was a member of these two groups. So too was Steven Rose — an important member of the Socialist Workers Party (see here); and Richard Lewontin (“the Marxist geneticist”).

These two groups didn’t want to make sure that scientific theories were apolitical or that scientists kept out of politics. They wanted to make sure that scientific theories and scientists were political in the correct (i.e., Marxist) ways. And, as Marxist groups, they tied much science to racism, capitalism and imperialism.

(See ‘Radical Science and its Enemies’, by Steven Rose and Hilary Rose.)

Thus it was no surprise that the International Committee Against Racism (INCAR) grew out of this atmosphere of scientific intolerance. This group attacked another scientist Stephen Jay Gould had serious problems with — E.O. Wilson (see here). In detail, just before Wilson gave a talk, the microphone was taken over by members of INCAR. They chanted:

“Racist Wilson you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide.”

Then these same activists rushed Wilson and poured a pitcher of ice water over his head.

Professor Elizabeth S. Anderson

Now take the case of Professor Elizabeth S. Anderson and a paper she wrote in 1995.

When I first began reading Anderson’s paper it seemed to be — at least in part — highlighting and criticising the political nature of both scientific theory and the political and technological uses of science. However, it turned out that it wasn’t the political use of science Anderson has a problem with. It’s the political use of science by scientists and governments with incorrect politics.

In terms of her technical detail, Professor Anderson isn’t simply arguing that political and ideological (to use her own terms) “value judgements” and “background assumptions” exist in all scientific theorising. Anderson is also making the political point that there are many politically-incorrect value judgements and background assumptions which underpin scientific theorising. In addition, scientific theories are often applied in ways that (to her at least) are politically objectionable.

This means that Anderson’s paper is just as much a work of politics as it is a work of epistemology or of the philosophy of science.

So if Anderson is correct to argue (which she does indirectly and in academese) that politics and ideology pervade all scientific theories, and that she additionally argues (again, often indirectly) that such politics and ideology should be politically acceptable (to whom?), then scientific theory (alongside epistemology and philosophy of science) effectively becomes a political battleground. Despite all that, it’s probably the case that Anderson believes that this scientific theory/politics “binary opposition” is false and political battles within science have always occurred anyway.

Professor Anderson, then, basically advances the position that all science is inherently political. (Historically, this was also the position of both the Nazi and Soviet states — see ‘Ideologically Correct Science’.) Thus it follows (to her at least) that epistemologists, philosophers of science and political activists (or at least those who share her own politics) must try their hardest to make sure that all science is both politically acceptable and ideologically correct. In that sense, then, Professor Anderson is no different to the Nazi mathematicians, Pascual Jordan and Stephen J. Gould.

Conclusion

There’s usually an element of truth in all these politicisations of science. Indeed they probably wouldn’t even get off the ground in the first place if that weren’t the case.

So, in Philip Goff’s case, the experiments he cites were probably scientifically kosher and carried out under strict conditions. (The tests may even be capable of being repeated.) However, what is relevant is how these experiments have been politically interpreted by Goff and others.

The same goes for Germanic mathematicians of the 1930s. Sociologically and historically it might well have been the case that Italian and French mathematicians (at that time) pursued different elements of maths — and did so in different ways - to German mathematicians, Yet is that a question of mathematics itself or merely one of culture and history?

Of course some activists and philosophical theorists will take this maths/culture binary opposition to be naïve.

No comments:

Post a Comment