The portrayal of both materialists and physicalists by particular types of anti-materialist (e.g., spiritual idealists, New Agers, religious commentators, etc.) makes it seem as if materialists are still stuck in the 19th century. In other words, their portrayals make it seem as if all the materialists of the 20th and 21st centuries were — and still are — either ignorant of 20th century physics, or that they’ve simply ignored it. Yet this anti-materialist take on materialism and physicalism will seem bizarre the moment you actually read contemporary materialists and physicalists. So what’s behind this portrayal?

In the following essay, the words “materialism” and “physicalism” are treated as synonyms. That’s mainly because all the “spiritual” anti-materialists mentioned in it also treat them as synonyms. More specifically, Gerald R. Baron (who’ll be discussed in the second part of this essay) never distinguishes physicalism from materialism. What’s more, he says very similar things about physicalism and physicalists as the spiritual idealist Bernardo Kastrup says about materialism and materialists. In addition, it would take a separate essay to fully distinguish these two terms.

Anti-Materialists Are Fixated on 19th Century Materialism

Anti-materialists (e.g., spiritual idealists, New Agers, religious commentators, etc.) conflate materialism with what many materialists believed in the 19th century and even before that — or, at the most, up until (roughly) the 1920s (i.e., before the rise of the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics). In other words, these particular anti-materialists have a view of materialism that might have been correct in the early 20th century — or well before that. Yet, by the 1920s, this stereotype of materialism was no longer the case when it came to most materialists.

All this largely boils down to anti-materialists claiming that materialists believe that all matter — and indeed everything else — is what they call “tangible stuff”. Indeed, the frequent claim used to be — and often still is — that materialists believe that everything is made up of “hard particles”.

Yet all that began to change with field physics in the 19th century — which nearly all materialists (who’re also naturalists) almost immediately took on board. Indeed, even a basic Wikipedia entry (which also helpfully distinguishes materialism from physicalism) states the following:

“Materialism is closely related to physicalism — the view that all that exists is ultimately physical. Philosophical physicalism has evolved from materialism with the theories of the physical sciences to incorporate more sophisticated notions of physicality than mere ordinary matter (e.g. spacetime, physical energies and forces, and dark matter). Thus, some prefer the term physicalism to materialism, while others use the terms as if they were synonymous.”

So why did naturalists and materialists take these changes in physics on board?

It was largely because such people weren’t mindlessly committed to tangible stuff — or to anything else like that. In fact, they were committed to the findings and theories of physics (as well as the other hard sciences). And physicists discovered fields (other than gravity) in the 19th century. [See here.]

In addition, when Albert Einstein showed that “matter and energy are interchangeable”, most materialists immediately took that on board too. Thus, as an obvious consequence of that, most materialists also came to believe that energy — not matter — was (as it were) prima materia. Or at least they came to believe that matter is a form of energy…

What’s more, something similar occurred with the rise of quantum field theory.

Again, many materialists took quantum field theory on board. In other words (as with Einstein’s equation of matter and energy), materialists came to see that fields — not energy — are (again, as it were) prima materia. Therefore, they also came to believe that energy is a property of such fields.

However, it must be stressed here that even if the technical details of the physics are sometimes wrong or misinterpreted by materialists (that includes my own accounts), the important point here is that although there were (radical) shifts in parts of physics, most materialists still took on board these new findings, commitments and theories.

So which materialists and physicalists, exactly, are these self-styled “anti-materialists” talking about?

Indeed, does this anachronistic stance on materialism explain why spiritual idealists, New-Agers, Jungians, people like Deepak Chopra, etc. rarely (if ever) quote any contemporary materialists and physicalists, let alone tackle the detail of their arguments? [See note.] Instead, they place a lot of emphasis on some artfully-selected quotes from Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, and other physicists (usually writing in the period long after the 1920s).

Those Artfully-Selected Quotes From Artfully-Selected Physicists

Much-quoted passages such as the following (from Werner Heisenberg's book Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science) are used to advance the Heisenberg-was-an-idealist-and-an-anti-materialist position:

“[The world of] atoms or the elementary particles [is one of] possibilities, rather than one of things or facts.”

Apart from that passage (at least in itself) being neither a direct nor an indirect argument for idealism (or for anything “transcendent”), we can move on to other quotes here.

Take the anti-materialist Deepak Chopra, who wrote the following:

“As Heisenberg put it, electrons and other particles are not real but exist only as ideas or concepts. They become real when someone asks questions about Nature, and depending on which question you ask, Nature obligingly supplies an answer.”

Elsewhere, we have this passage in the website Science & Nonduality:

“This phenomenon led physicist Werner Heisenberg to write in 1958, ‘The idea of an objective real world whose smallest parts exist objectively in the same sense as stones or trees exist, independently of whether or not we observe them [] is impossible.’ [].”

Yet no one is denying that Werner Heisenberg did indeed castigate 19th-century materialism (he refers to the 19th century below), as well as the materialism which existed immediately before the “quantum revolution” of the 1920s.

For example, Heisenberg put his position very simply when he wrote this passage:

“The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory has led the physicists away from the simple materialistic views that prevailed in the natural science of the nineteenth century.”

And, elsewhere, Heisenberg wrote the following words:

“The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct ‘actuality’ of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation, however, is impossible [] atoms are not things.”

[These words are also often quoted — especially in the “spiritual” memes found on Facebook and social media generally.]

In any case, many contemporary anti-materialists conflate materialism itself with 19th-century materialism. Heisenberg himself, on the other hand, had two specific things in mind when he made his critical remarks:

(1) 19th-century materialism (i.e., as a whole).

(2) Soviet dialectical materialism.

Heisenberg quoted one Soviet dialectical materialist and physicist Dmitry Blochinzev in the following passage:

“[] ‘Among the different idealistic trends in contemporary physics the so-called Copenhagen school is the most reactionary. The present article is devoted to the unmasking of the idealistic and agnostic speculations of this school on the basic problems of quantum physics.’ []”

So, according to this dialectical materialist (i.e., Blochinzev), idealism is “reactionary”. The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics (in his eyes) was idealist. Therefore, the Copenhagen interpretation was also reactionary.

Blochinzev’s main problem was that the Copenhagen interpretation didn’t abide by the dictates of dialectical materialism. Thus, Blochinzev quoted Lenin to back up his own position. And that passage, in turn, was quoted by Heisenberg himself. Thus:

“[] ‘However marvellous, from the point of view of the common human intellect, the transformation of the unweighable ether into weighable material, however strange the electrons lack of any but electromagnetic mass, however unusual the restriction of the mechanical laws of motion to but one realm of natural phenomena and their subordination to the deeper laws of electromagnetic phenomena, and so on — all this is but another confirmation of dialectical materialism.’[].”

As some readers will see, this almost reads like a religious tract which displays its loyal adherence to dialectical materialism. Indeed, Heisenberg himself picked up on this when he responded by saying that this defence of dialectical materialism

“seems to degrade [quantum theory] to a staged trial in which the verdict is known before the trial had begun”.

So readers can see why Heisenberg (as it were) had in in for materialism if his main and most influential experience of it (at least at one point) was Soviet dialectical materialism.

[Even as late as 2005, an article called ‘Against the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics — in defence of Marxism’ was published in the website In Defence of Marxism.]

All that said, it wasn’t only the Soviet dialectical materialists and 19th-century materialists whom Heisenberg had his eyes on.

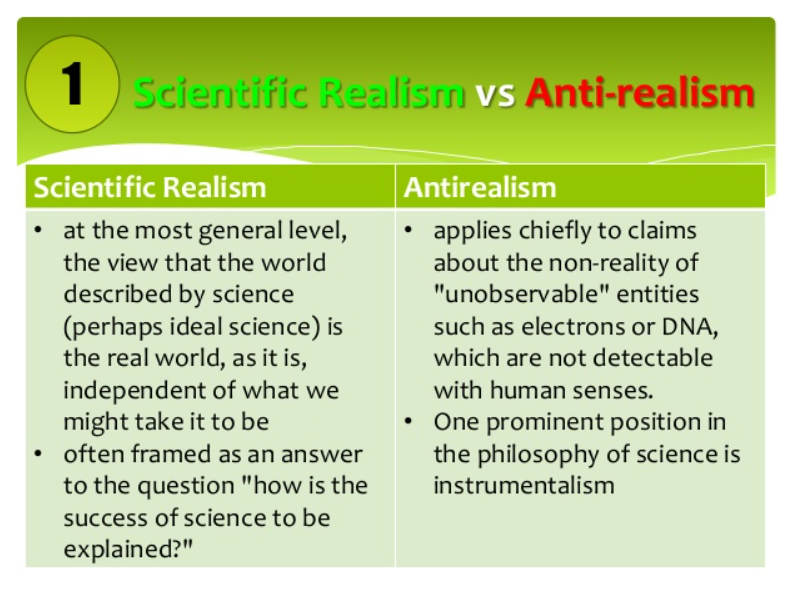

Materialism and Scientific Realism

Werner Heisenberg was certainly against scientific realism — or at least he was against what he called “dogmatic realism”. And it’s here that (at least to my 21st-century mind) Heisenberg appeared to conflate materialism with scientific realism…

What is the link between materialism and scientific realism?

Heisenberg might well have believed that materialism must lead to scientific realism, or that scientific realism must lead to materialism.

So do contemporary anti-materialists also view materialism as being a subset of scientific realism? (Idealists like Bernardo Kastrup certainly tie materialism and realism very closely together — see here.)

In specific reference to Albert Einstein, Max von Laue and (ironically enough) Erwin Schrödinger, Heisenberg wrote:

“[A]ll the opponents of the Copenhagen interpretation do agree on one point. It would, in their view, be desirable to return to the reality concept of classical physics or, to use a more general philosophic term, to the ontology of materialism. They would prefer to come back to the idea of an objective real world whose smallest parts exist objectively in the same sense as stones or trees exist, independently of whether or not we observe them.”

So, on Heisenberg’s reading, materialism is a kind of scientific realism. And scientific realists believe in what’s often called an “objective world”.

However, in Heisenberg’s own words:

“Quantum theory does not allow a completely objective description of nature.”

All that said, it’s true that materialism (being a philosophical position) needn’t always be naturalistic in nature. [See here.] That is, it needn’t be cognisant of the sciences and their findings. Indeed, in this case, clearly such scientific realists were rejecting the findings of physics — or at least they were rejecting the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory.

This meant that the physicists who were also scientific realists (just like contemporary “analytic metaphysicians”) believed that their personal philosophies could trump the findings of physics. [See the philosopher E.J. Lowe arguing for the the autonomy of metaphysics here.] In more clear terms, because the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory — and perhaps quantum mechanics itself — went against both “classical physics” and scientific realism, Einstein, von Laue, Schrödinger and Bohm (among others) believed that it must be wrong in some way. Thus, Heisenberg believed that their prior philosophies were telling them that the Copenhagen interpretation must be wrong!

This is how Heisenberg himself put it:

“[] Einstein hoped that beneath the chaos of the quantum might lie hidden a scaled-down version of the well-behaved, familiar world of deterministic dynamics.”

Yes, the above is an indirect reference to those famous hidden variables. Or, in Heisenberg’s own words again, a reference to

“a deeper level of hidden dynamical variables that effect the system and bestow upon it merely an apparent indeterminism and unpredictability”.

Thus, Heisenberg’s problem with materialism also (at least partly) stemmed from the accounts of what was deemed to be (philosophically) “objective” in physics. And, of course, any talk of what is objective has been tied to the philosophical position of scientific realism.

In any case, Heisenberg himself also wrote the following:

“The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct ‘actuality’ of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation is impossible, however.”

So this passage from Heisenberg won’t do much work for contemporary anti-materialists. That’s because Heisenberg was clearly restricting his claims to “the atomic range”. Spiritual idealists, New Agers, etc., on the other hand, apply their positions to the entire universe and literally everything in it. In other words, such people have “extrapolated” what Heisenberg and other well-known physicists said about the atomic range into the “the world around us”. Indeed, quantum entanglement is a good example of this New-Age, Jungian, etc. phenomenon. [See my ‘Carl Jung’s Wild Analogies: Synchronicity and Quantum Physics’.]

And this kind of thing was precisely what the much-quoted Heisenberg warned against.

To sum up.

With the rise of quantum physics and relativity theory in the 1920s, many physicists (not only Heisenberg) came to believe that the nature of matter (or the concept of matter) had been fundamentally altered…

And so too did most materialists, as well as all physicalists!

All the above has led on to the particular case of the Medium anti-physicalist writer Gerald R. Baron, whose words will be tackled in the next part of this essay.

Note:

The idealist Bernardo Kastrup has indeed engaged with some philosophers (whom he later abuses) outside his idealist (for want of a better word) school. He’d class most — even all — of these philosophers as “materialists”. However, as far as I can see, Kastrup has hardly debated the specific nature of materialism and/or physicalism with such philosophers. That said, his take on idealism-vs-materialism undergirds almost everything he writes and says.

So wee my ‘Bernardo Kastrup: The Idealist Cult Leader Who Endlessly Abuses Others’. I can now include the philosopher Tim Maudlin on the list of people Kastrup has abused. See also Kastrup’s own ‘My unfortunate attempt at debating Tim Maudlin’ from as recent as October 2023, in which he wrote the following:

“Maudlin’s unbecoming, unacademic and rude behaviour made it clear that such was not the case. He came across to me as a nasty and crass street brawler, not a thinker. [] Nor do I find his ungrounded, tendentious, hand-waving and wishful technical statements worthy of in-depth discussion in debate format. I am sure he can continue to believe in his unfalsifiable, pseudo-scientific fantasies without my help.”

No comments:

Post a Comment