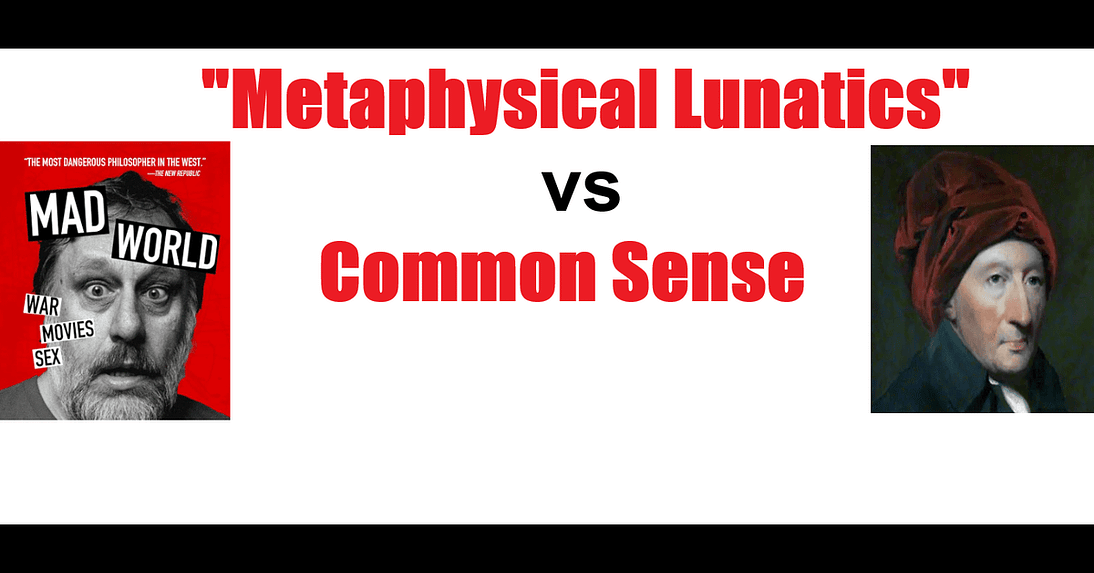

The Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid (1710–1796) used the words “metaphysical lunatics” about those philosophers who argued against “common sense principles” and beliefs. This essay will also discuss Reid’s influence on Ludwig Wittgenstein, as well as Herbert Marcuse’s attack on both “common sense philosophy” and Wittgenstein himself.

The common-sense beliefs that Thomas Reid had in mind included such things as “you exist and have a mind”, “this table is real”, “I exist”, and “I can have reason to trust my senses and testimony generally”. [See note 1.]

Most readers will accept that these examples are deemed to be common-sense beliefs by most people — even if only when pressed or asked questions about them.

All the examples above have been extensively dissected by various “metaphysical lunatics”.

A Philosophy You Can Live By

Thomas Reid and the commonsensicalists believed that philosophy should be unified with (as it’s often put) “the real world”.

According to the Scottish philosopher Alexander Broadie:

“As far as Reid is concerned, what this demonstrates is that there is something desperately wrong with Hume’s philosophy, because it is not a philosophy that you can live.”

It’s not immediately obvious why philosophy — Hume’s or anyone else’s — should have anything at all to do with what “you can live”. This position seems to erase truth itself from philosophy, and turn it into some vehicle for personal development, the advancement of religious/moral/political causes/goals, or pragmatic convenience. Thus, if the belief that “God loves [or hates] you” (or “The universe is conscious”) is something you can live by, then perhaps it doesn’t matter if it’s true or false.

Oddly enough, Hume’s own example shows this.

Hume was the first to admit that his philosophical conclusions had little or no impact on what he lived by. After all, he indulged in sceptical scenarios in the armchair, and then forgot about all of them when he went to play backgammon or billiards.

However, Hume might still have argued in the following manner:

Who cares if I ignore my sceptical conclusions when I play billiards or make love to a librarian?

Alternatively, Hume might have argued:

I haven’t, in fact, ignored my sceptical conclusions in my everyday affairs.

… Or at least Hume might have argued that he didn’t contradict his sceptical conclusions when he lived his life.

This way of looking at Humean scepticism was characterised by Melissa Lane in this way:

“There is a wonderful nineteenth-century Edinburgh story that said that really what happened was that Reid was shouting out very loudly, ‘We must believe in an external world,’ but whispering, ‘We have no reason for our beliefs.’ And then Hume saying very loudly, ‘We have no reason for our beliefs,’ but then whispering, ‘But we must believe in an external world.’ There is a sense in which, one can argue, are they in some ways saying the same thing?”

In this is a correct interpretation, then readers are just as warranted in arguing that Thomas Reid himself didn’t have a philosophy he could live by. After all, if it’s correct that he believed that “We have no reason for our beliefs” (yet we must believe in an “external world” all the same), then all he was doing was inverting Hume’s own position. Indeed, it’s an inversion which itself doesn’t make the slightest difference to what we live by. Of course, whether or not Reid did believe that “We have no reason for our beliefs” may just be speculation. After all, this is only part of a “nineteenth-century Edinburgh story”. That said, there may be an argument that Reid must have believed this — even if he never articulated it. In other words, Reid never demonstrated (let alone “proved”) that we do have reason for our beliefs. And, deep down, perhaps he knew that.

What’s more, if both Reid and Hume knew that the sceptical scenarios couldn’t be disproved (yet, nonetheless, we must ignore them outside the study), then what A.C. Grayling says about Hume adds meat to all this when he stated the following words:

“It may then be that Hume was not at all a sceptic about the external world, but about the potentials of reason to prove it.”

This makes sense. It does so because Hume didn’t have a problem with the existence of the external world: he had a problem with the grand claims of the rationalists.

Thomas Reid’s Philosophy

Let Thomas Reid himself articulate the basic principle of Common Sense Realism:

“If there are certain principles, as I think there are, which the constitution of our nature leads us to believe, and which we are under a necessity to take for granted in the common concerns of life, without being able to give a reason for them — these are what we call the principles of common sense; and what is manifestly contrary to them, is what we call absurd.”

In terms of phrasing alone, if “common sense” beliefs and values are those we needn’t “give a reason for”, then that may strike some readers as being very convenient indeed. At its most extreme, if I say that “Killing Welsh people is a common-sense belief”, then I needn’t reason — or argue — for that belief. So perhaps this extreme example is too particular to be a common-sense “principle”. After all, it’s not a belief about the existence of a chair, or other people, or time. That said, Reid did apply his common-sense philosophy to moral beliefs and values. [See here.] Indeed, Reid’s “first principles” grounded his own moral and religious beliefs. Thus, Reid’s common-sense philosophy went way beyond metaphysics and epistemology.

In any case, the section about common-sense principles being those “which we are under a necessity to take for granted in the common concerns of life, without being able to give a reason for them” squares very well with Ludwig Wittgenstein’s doubts about doubt, and the “hinges” on which all our reasonings depend.

In On Certainty, Wittgenstein put it this way:

“The questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those [doubts] turn.

“That is to say, it belongs to the logic of our scientific investigations that certain things are in deed not doubted…

“My life consists in my being content to accept many things.”

The main difference here is that Reid talked in terms of being under a necessity to accept certain principles, whereas Wittgenstein believed that (to put it simply) we can’t get the ball rolling unless we “exempt [certain propositions] from doubt”.

Not that an adherence to common sense was unthinking. It was a reasoned position. It also needs to be said that it wasn’t simply that, for example, Reid observed a table, and then argued that a belief in the existence of tables is “common sense”. His position on tables, etc. was based on “reflection” too. What’s more, Reid believed that our “faculties are all fallible”. In Reid’s own words:

“I can likewise conceive an individual object that really exists, such as St. Paul’s Church in London. I have an idea of it; I conceive it. The immediate object of this conception is 400 miles distant; and I have no reason to think it acts upon me or that I act on it.”

To state the obvious. Reid didn’t believe that St. Paul’s Church ceased to exist when he wasn’t observing it. Yet he might have concluded that Bishop Berkeley — and even some of the other empiricists - must have believed that…

Yes! Reid believed that these philosophers were metaphysical lunatics.

(It’s worth noting that this interpretation puts empiricists in exactly the same position as idealists.)

Finally, was the philosophy of common sense itself grounded on common sense?

Is Common-Sense Philosophy Conservative?

The danger of stressing “common sense” is that it can be used as a simple defence of the status quo. [See note 2.] The American philosopher Edward S. Reed picked up on this when he wrote the following words:

“[Whereas] Thomas Reid wished to use common sense to develop philosophical wisdom, much of this school simply wanted to use common sense to attack any form of intellectual change.”

So is it that the adherents of common sense don’t like “intellectual change”? This isn’t to say that intellectual change is always a good thing. And, politically, common sense may have a lot going for it… However, firstly it needs to be established what common sense is, and what beliefs and views fall under it.

On a mundane or anecdotal level, many people often simply mean my beliefs by their words “common-sense beliefs”. This has the consequence that “The earth is flat” and “The earth isn’t flat” can both be deemed to be common-sense beliefs by different people.

All that said, such everyday and mundane conceptions of common sense are certainly not identical to anything believed by Reid. Or at least it doesn’t seem so on the surface.

Reid’s philosophical — and indeed technical — account is that men (all men?) have an “innate ability to perceive common ideas”, and that such common ideas also exist alongside “judgement”. On the surface, this is a philosophical position on what common sense is. However, it can also be squared with conservative beliefs and views, and Reid’s philosophy may be taken as being mere (philosophical) gloss on conservativism (i.e., with a small ‘c’).

Despite all that, readers mustn’t automatically assume that common-sense philosophy was conservative… at least not in the 18th century. After all, the Scottish school of philosophers provided scientific accounts of historical events. They also believed that education should be free from religious and political dogma. Indeed, common-sense philosophy was part of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Marcuse on Common Sense and Wittgenstein

One philosopher who most certainly did believe that common-sense philosophy (or even just plain common sense) is conservative (or “reactionary”) was the German-American philosopher and political theorist Herbert Marcuse.

Marcuse argued that common sense is a weapon of ideology. Or, at the very least, he argued that it could be — and often has been — such a weapon. Moreover, an adherence to common sense actually “obscures reality”, and, in so doing, upholds existing power structures.

In terms of its affect on individual people. An adherence to common sense leads to a lack of critical thinking, intellectual sterility, and, more importantly, a blind acceptance of the status quo.

Earlier, Wittgenstein was tied to Thomas Reid, and the former was a particular target of Marcuse.

Take Wittgenstein’s claim (which will be very familiar to all those who’ve read his work) that philosophy “leaves everything as it is”. Marcuse believed (as found in his book One-Dimensional Man) that Wittgenstein’s statement is one of “academic sadomasochism [and] self humiliation”. He also believed that it was a “self denunciation of the intellectual whose labour does not issue in scientific, technical or like achievements”.

Marcuse interpreted the words “leaves everything as it is” as Wittgenstein stating that “the existing structure of society is all right as it is”, whereas other philosophers interpret Wittgenstein as arguing that only “language is all right as it is”.

Earlier it was said that common-sense philosophers believed that philosophy should be something to live by, and then Wittgenstein was tied to Reid, yet Marcuse believed that Wittgenstein, J.L. Austin and other linguistic philosophers had (in the words of Colin Lyas) “detached philosophy from its traditional concern with the large issues of life and rendered it trivial”.

Notes:

(1) The reference to “testimony” seems like the odd man out here. It can be doubted that many people would argue that a belief (or trust) in testimony has much to do with common sense. [See the ‘philosophy of testimony’.]

(2) The Conservative Party of the United Kingdom, right up until the 1990s and beyond, often talked about “common sense”. [See here.] And, as can be guessed by some readers, Marxist/Leftist commentators took a Marcusian position on such utterances. It’s certainly the case that Conservatives have often argued that they don’t indulge in what they called “theory”. Yet this is clearly false: they simply don’t like certain types of theory. As for Conservative leaders and politicians, many of their ideas and policies are both based on theory and are world’s away from being common sense. Then again, the essay above has partially shown that this is a problematic notion anyway, and is only on secure ground when it involves body counting what various populations believe.

No comments:

Post a Comment