The following is an essay on various good, bad and commonplace examples of ordinary language philosophy.

In 2003, the American philosopher Hilary Putnam offered his own not-entirely-critical retrospective on the same subject. Indeed, he offered some examples of “traditional” philosophical locutions which ordinary language philosophers would have deemed to be suspect:

“The fact that we never speak of ‘directly perceiving’ and ‘not directly perceiving’ in everyday language in the way that traditional epistemologists do was a sign that something was really quite wrong with the traditional philosophy of perception, something already noticed in the eighteenth century by Thomas Reid, by the way. Reid sounds very Austinian when he fulminates against the strange ways philosophers talk about perception. I think that’s a corrective one should apply to one’s own thought.”

It’s no doubt true that the phrases “directly perceiving” and “not directly perceiving” are somewhat contrived (i.e., regardless of one’s philosophical position on this) — but so what!

The problem with Putnam’s position above is that it may not (or will not) allow philosophers any leeway to say anything new because that would be bound to go against the dictates of “everyday language”. Would we say the same kind of thing to poets when they use a strange metaphor — that they too are going against everyday language? (Herbert Marcuse’s and Jacques Derrida’s criticisms of ordinary language philosophy will be mentioned later.)

In addition, the very fact that philosophy is an academic discipline (that is, a specialism) surely means that it’s bound to say novel things in novel ways. Indeed the American philosopher Richard Rorty, for example, argued that it’s the duty of philosophers to say strange things in strange ways. [See here.]

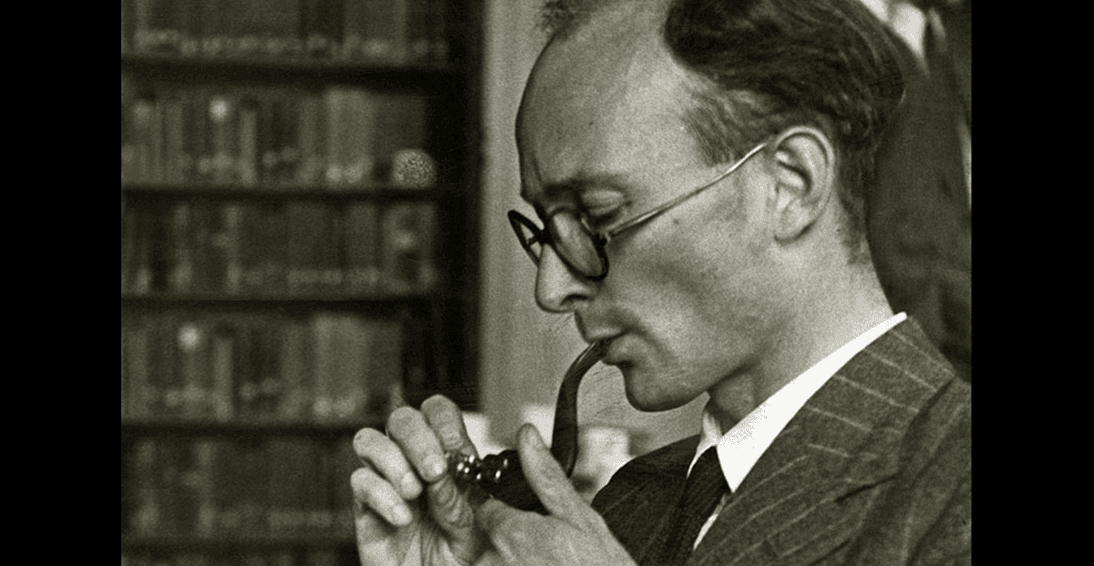

Was J.L. Austin a Conservative Philosopher?

Jacques Derrida, and Herbert Marcus before him, categorised the ordinary language philosopher J.L. Austin as a “conservative philosopher”. In my own view too, he was. However, both Marcuse and Derrida meant it as a criticism which was somewhat equivalent to calling someone a paedophile. However, it needn’t be critical. It simply depends.

The following oft-quoted passage best sums up Austin’s conservatism:

“Thirdly, and more hopefully, our common stock of words embodies all the distinctions men have found worth drawing, and the connexions they have found worth marking, in the lifetime of many generations: they surely are likely to be more numerous, more sound, since they have stood up to the long test of the survival of the fittest, and more subtle, at least in all ordinary and reasonably practical matters, than any that you are I are likely to think up in our arm-chairs of an afternoon — the most favoured alternative method.”

Taken at face value, there are obvious problems with that passage. For one, how can it be known that

“our common stock of words embodies all the distinctions men have found worth drawing, and the connexions they have found worth marking, in the lifetime of many generations”?

Say that Austin wrote this a hundred or a thousand years before he actually did write it. Would it have still been the case that “our common stock of words embodies all the distinctions men have found worth drawing”? Not all men have access to all distinctions and connections. Some men make distinctions and connections which are at odds with other men. And is it really the case that each generation of “ordinary men” reach the limit of all “sound” and worthwhile distinctions and connections?

In addition, the distinctions and connections made may be false, and yet they still (to use Austin’s word) “survive”. More precisely, Austin mentioned “the long test of the survival of the fittest” — yet many evolutionary theorists will tell you that truth is often not needed when it comes to survival. For example, many religious beliefs are obviously false, yet they may be conducive to survival in various circuitous ways. Moreover, false “commonsense” beliefs may also be conducive to survival, and the “fittest” may believe more falsehoods than the weakest.

Finally, it doesn’t seem out of the question that (at least sometimes) the connections and distinctions philosophers “think up in [their] arm-chairs of an afternoon” are truer, more correct, or even more useful than those thought up by what Austin calls “men”.

J.L. Austin is Boring

Many commentators have found Austin’s philosophy to be boring or almost pointless. Thus, it’s no surprise that the American philosopher Thomas Nagel said that “J.L. Austin was fascinated by many details of language for their own sake”. So here’s an example of that:

“‘It was a mistake,’ ‘It was an accident’ — how readily these can *appear* indifferent, and even be used together. Yet, a story or two, and everybody will not merely agree that they are completely different, but even discover for himself what the difference is and what each means.”

Perhaps it was the Austinian tradition that made that sad person complain about “split infinitives” when the newsreader announced the shooting of Pope John Paul II. In other words, Austin’s kind of analysis can lead to mere pedantry, rather than philosophical insight.

In any case, do many — or even any — people deem the phrases “It was a mistake” and “It was an accident” to be literal synonyms? I doubt it. Perhaps, then, Austin wasn’t claiming that people believe they are synonyms. However, they still go on to use them interchangeably. Moreover, can using these phrases interchangeably really lead to any serious consequences? It can be supposed that they could do in various contrived scenarios in which people really do believe that they’re literally synonymous phrases.

Austin is also well-known for bringing in the notion of a “speech-act”. He did so primarily because he claimed that philosophers (at least the ones he was concerned with) believed that sentences are only used to state facts or describe states of affairs… Philosophers, surely, couldn’t have believed that. After all, even analytic philosophers or German “system-builders” must have used phrases such as “Shut that door” or “Shut the fuck up”. Instead, didn’t such philosophers simply focus on fact-stating sentences for various philosophical and logical reasons?

Logical Form

It’s often said that the primary ordinary-language position was that “philosophical problems are largely a product of the misuse, or misconstrual, of language”. (This was basically Ludwig Wittgenstein’s position at one point in his career.) Of course, it’s hard to decipher what that could even mean without doing a lot of background reading.

Prima facie, any claim that language is “misuse[d]” or “misconstru[ed]” is surely suspect, and that applies just as much to ordinary-language philosophers as it did to the “early Wittgenstein” and Bertrand Russell. According to the ordinary philosophers, philosophical discourse is misused and misconstrued when it moves too far away from ordinary language. On the other hand, according to the tradition the ordinary philosophers reacted against, language is misused or misconstrued because ordinary folk don’t understand what it is they’re actually saying.

So why is “everyday usage” or, alternatively, “logical form” something that should be obeyed… in all circumstances? More strongly, language can only be misused or misconstrued according to a prior philosophy or ideology. In other words, only through the prism of that philosophy or ideology is language misused and/or misconstrued.

All that said, I believe that J.L. Austin was right about the early-20th-century concern with logical form.

Firstly, let Bertrand Russell speak for himself:

“Some kind of knowledge of logical forms, though with most people it is not explicit, is involved in all understanding of discourse. It is the business of philosophical logic to extract this knowledge from its concrete integuments, and to render it explicit and pure.”

The logical form was supposed to be there all along — underneath or behind everyday expressions. Thus, it was the philosophers job to dig deep and discover the logical forms of everyday and of (prior) philosophical expressions.

Now take this passage from Russell:

“The fact that you can discuss the proposition ‘God exists’ is a proof that ‘God’, as used in that proposition, is a description not a name. If ‘God’ were a name, no question as to existence could arise.”

W.V.O Quine (for one) had no problem at all with the naming of non-beings or non-existents. (Non-being and non-existence aren’t the same thing.) In his 1948 paper, ‘On What There Is’, he dismissed Russell’s position. (Quine, however, put Russell’s words in the mouth of McX and used the name “Pegasus” rather than the name “God”.) Quine wrote:

“He confused the alleged named object Pegasus with the meaning of the word ‘Pegasus’, therefore concluding that Pegasus must be in order that the word have meaning.”

So was Russell misled by grammar and metaphor, as the late Wittgenstein might well have argued? (Admittedly, Russell didn’t often use the words “underneath” and “behind”. However, he did use such words as “extract this knowledge”.)

Personally, I don’t have much time for Russell’s argument about the logical forms underneath or behind everyday expressions. It seems to have the character of a philosophical stipulation. (As with the logical positivists’ use of the word “meaningless”!) It’s primary purpose was logical and philosophical. (At that time, Russell was reacting to the, as Quine later put it, “ontological slums” of the Austrian philosopher Alexius Meinong.) However, this semantic philosophy (as stated) simply seems like a stipulated (or a normative) position designed to solve various perennial philosophical problems.

No comments:

Post a Comment