i) A Little Context: Hoffman on Religion, Spiritualism and Mysticism

ii) Conscious Realism

iii) Conscious Realism and Fundamentality

iv) Consciousness

v) Conscious Agents

vi) Interfaces and Icons

vii) First-Person Science and the Copenhagen Interpretation

A Little Context: Hoffman on Religion, Spiritualism and Mysticism

This introduction deals with the context of — and what might have motivated — Professor Donald Hoffman’s philosophical position of consciousness realism. Admittedly, it’s usually commentators on — and interviewers of — Hoffman who’re very keen to stress the religious, spiritual and mystical aspects of his philosophy. However, Hoffman himself does so in various places.

So in order to place Professor Donald Hoffman’s conscious realism in some kind of context, it may be wise to look at what can be taken to be his non-philosophical and non-scientific motivations.

From what he writes himself, and from the many comments he’s made on spirituality, mysticism and religion (as well as the time he has given to people like Deepak Chopra, etc.), it seems that there are many non-philosophical and non-scientific motivations behind Hoffman’s conscious realism. This, of course, isn’t to claim that Hoffman doesn’t provide arguments and scientific data for his speculative philosophy. Nonetheless, this context may help us understand what it is Hoffman is attempting to do.

The bottom line is that there’s much that Hoffman states which seems to be tailor-made for those who have religious, spiritual and mystical (i.e., non-scientific and non-philosophical) views of what “reality” truly is. For example, take these words from Hoffman:

“According to conscious realism, you are not just one conscious agent, but a complex heterarchy of interacting conscious agents, which can be called your instantiation (Bennett et al. 1989 give a mathematical treatment).”

Clearly Hoffman is advancing some kind of “holistic” interconnectedness vibe (for want of a more suitable word) here.

Having said that, the fact that New Agers, etc. are now gobbling up Hoffman’s words and theories doesn’t automatically make them false or unscientific. This would be an example of relying on guilt by association. However, it does give people grounds for varying degrees of suspicion or scepticism.

It can be said that much of what Hoffman says is also closely connected to “mysticism”. That’s not my own word, Hoffman himself uses it a few times. (He does so usually in interviews and seminars, rather than in his academic papers.) Despite that, Hoffman does (at least at times) distance himself from such things. He does so primary by saying that his position

“give[s] a mathematically precise theory of conscious experiences, conscious agents, and their dynamics, and then make empirically testable predictions”.

So Hoffman’s rejoinder may be that he’s certainly not doing religion, spiritualism or mysticism because of the scientific nature of his theories. Yet it can still be argued that the very least Hoffman should say is that he’s not only doing religion, spiritualism or mysticism.

Now let’s ignore whether or not there are genuinely scientific aspects to conscious realism (there obviously are!) and put forward the fact that Hoffman’s science is used to advance positions (at least in part) which already existed long before — and independently of — all science. (He concedes as much here.) That, of course, doesn’t mean that the two independent magisteria of science and religion/spirituality/mysticism can’t be squared. Indeed I believe that Hoffman himself is attempting to square them.

Finally, the term “magisteria” has just been used. This is Stephen Jay Gould’s term and it’s been quoted by Hoffman himself. However, it can be argued that since Hoffman is attempting to literally fuse (or unite) these two magisteria (i.e., science and religion), then that must surely go against what Gould himself had in mind — i.e., his stress on the mutual independence of science and religion.

(See this video in which Hoffman presents himself as offering a midway position between theism/deism and atheism. Later in the same video, Hoffman concedes that he’s “giving religious people something that will be positive to them”. And here Hoffman argues that all the scientific cases against the existence of God fail. Finally, in this interview Hoffman says that the relationship between science and spirituality is “very deep”. More specifically, Hoffman states that “many of the spiritual traditions have been telling us for centuries, even millennia, that spacetime is not fundamental but there’s a deeper reality outside of spacetime”. Of course Hoffman will be keen to stress than none of these positions make him either a religious person or a theist/deist. So does Hoffman have his cake and eat it too?)

Conscious Realism

The prime thesis of Donald Hoffman’s conscious realism (CR) is very radical. In Hoffman’s own words:

“Conscious realism asserts that the objective world, i.e., the world whose existence does not depend on the perceptions of a particular observer, consists entirely of conscious agents.”

Of course the word “radical” doesn’t mean “false”, “incorrect” or even “misguided”. Indeed Hoffman himself acknowledges (as well as plays upon) the fact that CR seems incredible.

To get the obvious out of the way. It’s clear that the realism in conscious realism applies to consciousness or to what Hoffman calls “conscious agents”. That is, Hoffman is realist about consciousness (or about the contents of consciousness).

It is the final clause of the quote above (“consists entirely of conscious agents”) which is peculiar to Hoffman. On the other hand, the preceding statement about “the objective world” (i.e., the world whose existence does not depend on the perceptions of a particular observer”) has of course be well played out in philosophy for over the two millennia.

To rush ahead of myself, that “objective world” does indeed exist. The point is that it’s not what “we” take it to be. So what should we take the objective world to be? According to Hoffman, the objective world “is a world of conscious agents”. It’s “not a world of unconscious particles and fields”. So since particles and fields have just be mentioned, what does Hoffman take them to be? He takes them to be “icons in the [multimodal user interface] of conscious agents”. Thus particles and fields are “not themselves fundamental denizens of the objective world”.

The end result of Hoffman’s philosophy is that consciousness must be taken to be “fundamental”.

Conscious Realism and Fundamentality

Firstly, Hoffman says that

“[b]rains do not create consciousness; consciousness creates brains as dramatically simplified icons for a realm far more complex, a realm of interacting conscious agents.”

One may ask here how can it be that some non-material reality or thing can create anything? However, if Hoffman believes that “consciousness is fundamental”, then one can suppose that the answer is embedded in that position.

So conscious realism has it that “conscious experience [is] ontologically fundamental”. Thus, if that’s the case, conscious experience simply can’t arise from anything else. Or as Hoffman himself puts it:

“If experiences are ontologically fundamental, then the question simply does not arise of what screen they are painted on or what stuff they are made of.”

More specifically, Hoffman compares consciousness to space-time and leptons. That is:

“If space-time and leptons are taken to be ontologically fundamental, as some physicalists do, then the question simply does not arise of what screen space-time is painted on or what stuff leptons are made of. To ask the question is to miss the point that these entities are taken to be ontologically fundamental. Something fundamental does not need to be displayed on, or made of, anything else; if it did, it would not be fundamental.”

Hoffman also offers us something which I take to be (almost) a non sequitur. Firstly he says that “[e]very scientific theory must take something as fundamental”. Then he says that “no theory explains everything”.

One consequence of Hoffman seeing “conscious experiences” as being fundamental is that

“they are not existentially dependent on the brain, or any other physical system”.

All this means that the philosopher David Chalmers’ well-known question

“Why does a physical x give rise to experience y?”

is misplaced. That’s simply because that physical x doesn’t give rise to experience y: experience y is fundamental. And if it’s fundamental, then how can anything at all give rise to it? This chimes if with the position of most/all panpsychists in that they too believe that experience/consciousness is fundamental. Thus experience can’t emerge from anything nor can anything give rise to experience. The difficulty here, however, is that Hoffman distances his conscious realism from panpsychism.

Consciousness

Hoffman states that consciousness

“is not a latecomer in the evolutionary history of the universe, arising from complex interactions of unconscious matter and fields”.

Instead:

“Consciousness is first; matter and fields depend on it for their very existence.”

There are two (perhaps) kneejerk readings of this position. 1) That it is idealist. 2) That it is panpsychist.

Hoffman’s multi-dimensional user interface (MUI) position appears to be a new version of idealism because it states that consciousness is (as already stated) fundamental. More strongly and in tune with idealism, Hoffman claims that “matter and fields depend on [consciousness] for their very existence”. Alternatively, “[c]onsciousness is first”.

However, Hoffman doesn’t exactly reject “matter” (as many/all old-style idealists did). Instead he believes that “matter is derivative” — it’s “among the symbols constructed by conscious agents”. The question is whether or not this 21st century way of putting things extracts Hoffman from being a basic idealist. After all, Bishop Berkeley accepted matter; though he believed that matter is a question of our “sense impressions” or “ideas”. Hoffman, on the other hand, sees his “icons” (not sense impressions or ideas) as stand-ins for “objective reality”.

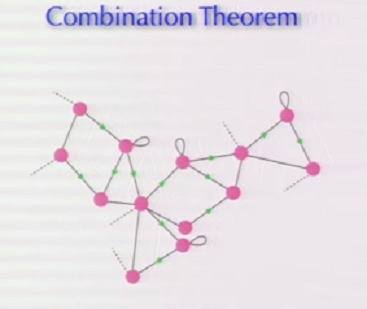

Conscious Agents

The most difficult part of Hoffman’s conscious realism to understand is his notion of conscious agents and what part they play in his overall philosophy.

Hoffman’s position on conscious agents is the most radical aspect of an already radical philosophy. So let Hoffman himself explain things. He writes:

“According to conscious realism, when I see a table, I interact with a system, or systems, of conscious agents, and represent that interaction in my conscious experience as a table icon.”

Now that — at least on its own — hardly makes sense. For a start, what does it mean to “interact with a system, or systems, of conscious agents”? (As stated earlier, we’ll need to elaborate of what a conscious agent is first.) And what does it mean to “represent that interaction in my conscious experience as a table icon”?

Hoffman doesn’t answer these questions — at least not in the section just quoted. Instead he offers some more seemingly bizarre philosophy when he writes:

“Admittedly, the table gives me little insight into those conscious agents and their dynamics.”

Again, what does Hoffman mean by “conscious agents” and what does the statement “the table gives me little insight into those conscious agents and their dynamics” mean? Instead, Hoffman quickly moves on and tells us that the

“table is a dumbed-down icon, adapted to my needs as a member of a species in a particular niche, but not necessarily adapted to give me insight into the true nature of the objective world that triggers my construction of the table icon”.

It is then that Hoffman appears to answer these questions. Firstly, he writes:

“When, however, I see you, I again interact with a conscious agent, or a system of conscious agents. And here my icons give deeper insight into the objective world: they convey that I am, in fact, interacting with a conscious agent, namely you.”

So, at least in this instance, a conscious agent is a person or a fellow human being. (It can be seen here that Hoffman stretches his term “conscious agent” wider than that.) The first statement of the quote above (i.e., “When, however, I see you, I again interact with a conscious agent, or a system of conscious agents”) is fairly innocuous. However, the second statement (i.e., “… here my icons give deeper insight into the objective world: they convey that I am, in fact, interacting with a conscious agent, namely you”) is a little harder to make sense of.

Does Hoffman mean that by “interacting” with other conscious agents we get a “deeper insight” into the table or “objective world” than we would do by simply interacting with the table (or the objective world) itself? Well, he must do. That’s because Hoffman believes that the table is just an “icon” and objective reality isn’t what we think it is. Conscious agents, on the other hand, aren’t icons. What’s more, it is we (as conscious agents) who constitute objective reality. Thus if we want to know about this table, we must do so through our interactions with other conscious agents, not directly by observing the table itself.

But what does all that mean?

Does Hoffman mean that we can find some kind of objectivity (as it were) only by discovering what’s going on in the heads (heads are icons too) of other conscious agents? Do we do this by talking to them? And if that’s the case, then what position should we take on their words and on their phenomenological experiences (which includes icons) of the aforesaid table? (See the final section on Niels Bohr and the subjective and intersubjective elements of relativity and quantum theories.)

To sum up. Steve Tolley captures the main problem with Hoffman’s conscious realism. That problem is Hoffman’s seemingly quick and easy move from scientific facts (i.e., from cognitive science, evolutionary theory and physics) to philosophical speculation. So take this expression of that philosophical jump. Tolley writes:

“Hoffman is not doing science, he constructs a solipsistic metaphysics based on illogically elevating the simple fact that our experience of something is filtered through our perceptual apparatus to the metaphysical axiom that this entails there are no public objects.”

In other words, Hoffman feels the need to move beyond what can be regarded as anti-realism to embrace what seems to be an old-style idealism (if with technical terms from cognitive science, physics and evolutionary theory). That is, from the fact that your experience of a spoon/table/tomato isn’t identical to my experience of a spoon/table/tomato, Hoffman derives the metaphysical conclusion that the spoon/table/tomato only exists in one person’s head or in many persons’ heads. Yet Hoffman fails to realise that metaphysical realists — and even naïve realitists — have never claimed that all experiences of the same spoon/table/tomato (at the same time) need to be identical. All these realisms simply argue that there’s a spoon/table/tomato which is beyond all acts of consciousness and experience. However, unlike anti-realists, naïve and metaphysical realists believe that we can get that spoon/table/tomato as it is in itself. Hoffman, on the other hand, believes that the spoon/table/tomato (as an “icon”) is entirely in our consciousnesses.

Interfaces and Icons

When we have talk of “icons”, then there’s often also talk of “interfaces”.

Is Hoffman’s notion of an interface a resurrection of the ancient philosophical notion of the “veil of perception” (or the recent science of the “hologram”)? That is, Hoffman believes that we never have access to objects as they are (to use a well-worn phrase) “in themselves”. Instead, we rely on our interfaces with the icons which stand in for (as it were) objects. Alternatively, is it that we’re to take the icons as the objects?

At least, then, Hoffman is accepting the existence of objects, etc: it’s just that we don’t get them as they are. (In that case, the icons aren’t the objects.) In philosophical terms, interfaced icons are equivalent to phenomena, not to noumena. Is Hoffman, therefore, ploughing over ancient ground with up-to-date jargon?

So what does Hoffman mean by “interface”? Let the cognitive scientist himself explain. He writes:

“So what is space-time and what are our perceptions of objects? I think a good way to think about them is that they are just a user interface. We evolved a user interface. If you’re crafting an e-mail on your computer and the icon for the e-mail is blue and rectangular and on the right corner of your screen, that doesn’t mean that the e-mail in your computer is blue and rectangular and in the right corner of your computer.”

What’s more:

“The interface is not there to resemble reality. It’s there to hide reality and to give you eye candy that lets you do what you need to do. That’s what evolution did. 3D space is our desktop. Physical objects are the eye candy. They are there not to show us the truth but to hide the truth and let us act in ways that keep us alive.”

First things first. The obvious point to make here is that “user interfaces” on a computer are consciously designed to serve a specific purpose. Now that may be a difference that doesn’t make a difference to Hoffman. (After all, some people use the word “design” to refer to the changes evolution brings about in homo sapiens and other species.) Nonetheless, are we really supposed to accept that an “icon for the email” is the same kind of thing as the icon that is a table which we experience in everyday life? Perhaps the two examples are simply similar. Or perhaps they’re merely analogous. However, reading what Hoffman actually writes can lead one to believe that the cases are indeed the same; even if one icon is on a computer and the other is an experience of an icon of a table.

Let’s unpack this a little more. Firstly we have this:

“An icon for an email which is blue and rectangular and which appears on the right-hand side of a computer screen.”

But what is this icon an icon of? It’s an icon of the wires, electrical currents, etc. which exist within the computer and which are the “subvenience base” (as it were) of the email.

What’s more, icons — being icons — are mere “eye candy”. That is, Hoffman believes that icons don’t “resemble reality”. Instead, they “let us do what we need to do”. And we can do what we need to do without these icons resembling reality or by their “show[ing] us the truth”. In fact they “hide the truth”. Now why would icons do that? Hoffman believes that they do so in order to “keep us alive” (or at least the icons outside of computers keep us alive).

The words “eye candy” don’t help because they imply (at least to me) that icons (even if we accept this term) have absolutely nothing to do with what Hoffman calls “reality”. Thus our icon of a table has absolutely nothing in common with whatever underpins (if that’s the right word) our experience of a table; just as an icon on a computer has nothing in common with the innards of a computer. This, again, raises the simple question:

Can what is true about an icon for an email on a computer screen easily and smoothly pass over to the icon we experience and which we take to be a table?

Again, are these examples similar or merely analogical? If they’re dissimilar in any way, then we’d need to know how they’re dissimilar. We’d also need to know if these dissimilarities had any heavyweight philosophical consequences.

Firstly, we know what’s “behind” the icon on a computer — Hoffman has told us about what’s behind it and we can happily agree with him. So what’s behind the icon/s of, say, a table? And whatever it is that’s behind the icon/s of a table, does it have anything in common with our icon/s?

As stated, Hoffman answers this question by arguing that the icon of a table has absolutely nothing in common with what’s behind it. (In his own words, it is “utterly different”.) Or to use Hoffman’s next example of a red tomato, he writes:

“When I open my eyes and I have a conscious experience that I describe as a red tomato one meter away, I’m interacting with something, but that something is not a red tomato and it is not in space and time. It’s something utterly different.”

So if it is not a red tomato and “it is not in space and time”, then what is it? One’s first temptation is to say that it’s a Kantian noumenon. After all, Kant’s noumena were also meant to be outside space and time. However, elsewhere Hoffman rejects (Kantian) noumena because he claims that they aren’t scientific in nature.

First-person Science and the Copenhagen Interpretation

Apart from the technicalities and technical terms of Hoffman’s philosophy, he also takes a very radical position in what can be called the philosophy of science. Basically, Hoffman rejects what he calls “third-person science”. It’s partly because of this that he also rejects “physical objects”. Hoffman says that

“you can look at this physical object and I can look at the same physical object and we can both make measurements on it and then compare”.

Hoffman rejects this fact (or this ideal) because he believes that “there are no public physical objects”. Essentially, what’s being compared is what goes on in my head with what goes on in other people’s heads. As a consequence of that, Hoffman believes that “[s]cientists will also have to give up the idea of third-person science” and opt for “first-person science”.

Much of what Hoffman says can therefore be traced back (as he does himself) to Niels Bohr and the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. For example, take these words from Hoffman:

“What one gives up in this framework of thinking is the belief that physical objects and their properties exist independently of the conscious agents that perceive them.”

We can easily do some word substitutions here to arrive at the following:

What one gives up in this framework of thinking is the belief that physical objects and their properties exist independently of the experiments and observations that give rise to them.

The problem is that the quantum physicists of the 1920s were talking about the quantum realm, not the realm of “medium-sized dry goods” (as J.L. Austin once put it). However, that’s a difference that doesn’t make a difference to Hoffman. That is, Hoffman believes that what has been said about the objects, events and items of the quantum realm can also be said about “classical” objects (such as his own table and red tomato).

And, more specifically, perhaps Niels Bohr’s take on Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity (among other things) have also influenced Hoffman. That is, is Hoffman is stressing his own equivalent of the scientific emphasis on “intersubjective” communication, observation and experiment?

Nonetheless, Bohr did note the problem with over-stressing what he called the “subjective element”. Or at least he did so when it came to Einstein’s theories of relativity. For example, Bohr said that “we have come a long way from the classical ideal of objective descriptions”. And Bohr made roughly the same point elsewhere when he said that “every physical process may be said to have objective and subjective features”. He continued:

“Admittedly, even in our future encounters with reality we shall have to distinguish between the objective and the subjective side, to make a division between the two. But the location of the separation may depend on the way things are looked at; to a certain extent it can be chosen at will.”

To put all that in more basic terms. It’s clear that Bohr’s position (or positions) could never be deemed to be entirely subjectivist. Indeed isn’t that obvious? Though, as we’ve seen, there is indeed an element of subjectivism (or experientialism) in Bohr’s statements.

No comments:

Post a Comment