i) Introduction

ii) Does Penrose Go Beyond Mathematics?

iii) Gödel, Turing, Penrose

iv) Beyond Mathematical Platonism?

v) Seeing Truths

vi) Do Platonic Truths Stand Alone?

vii) Penrose’s Rationalism

viii) Laurence BonJour: A Rationalist of the 21st Century

vix) Conclusion: Is Roger Penrose Really a Platonist?

The following piece is about what the theoretical physicist and mathematician Roger Penrose has said about “seeing” certain mathematical truths. Penrose’s overall Platonic position is also discussed. Indeed the question as to whether Penrose actually has an overall Platonic position is also asked.

But before all that, let’s place Penrose’s position in some kind of context.

ii) Does Penrose Goes Beyond Mathematics?

Penrose has been very open-minded about (as it were) Platonic seeing when it comes to such things as “beauty” and “goodness”. Despite that, he’s never done any detailed work on any of these strictly philosophical issues. Much of what Penrose has said has been the result of interviewers pressing him on subjects which aren’t his speciality . (In most cases these have been attempts — by such interviewers — to get Penrose to backup their own prior religious or spiritual views — see here for a perfect example of this.)

One aspect of the wider context of Penrose’s Platonism concerns his deflationary position on “algorithmic thinking”. And, as a consequence of that position, his critical position on the possibility of strong artificial intelligence; as well as his controversial views on human consciousness.

And this is where the Austrian mathematician and logician Kurt Gödel inevitably enters the picture.

Let Penrose himself tell you about his first encounter with Gödel’s work and what effect it had on him. He wrote:

“Why did I believe that consciousness involves noncomputable ingredients? The reason is Gödel’s theorem. I sat in on a course when I was a research student as Cambridge, given by a logician who made the point about Gödel’s theorem that the very way in which you show the formal unprovability of a certain proposition also exhibits the fact that it’s true.”

What follows is perhaps more relevant to this piece. Penrose continued:

“[A]s long as you believe in the rules [of “any system of rules”] you’re using in the first place, then you must also believe in the truth of this [Gödel] proposition whose truth lies beyond those rules.”

And now for the relevant (as it were) clincher:

“This makes it clear that mathematical understanding is something you can’t formulate in terms of rules.”

This is where Platonic seeing comes to the rescue. Penrose believes that no machine (or computer) can have Platonic vision. That is, “we have a proposition that we can see [Penrose’s italics], by the use of insight, must actually be true”. However, “the given algorithmic action is not capable of telling us this”.

Penrose then goes into greater detail when he asks us this question:

“Why, then, can one not simply get a computer also to follow this Gödel argument and itself ‘see’ the truth of any new Gödel proposition?”

“The catch lies in ‘seeing’ that the Gödel argument, in any specific realization, has actually been correctly applied. The trouble is that the computer does not have a way of judging truth; it is only following rules. It does not ‘see’ the validity of the Gödel argument. It does not ‘see’ anything unless it is conscious!”

It may of course be asked how literally Penrose wants his readers to take his words “seen”, “see”, “seeing” and “vision”. After all, Penrose himself used scare quotes in the passage above. However, scare quotes can sometimes be somewhat ambivalent. On the one had, they can be used ironically or questioningly. (As Heidegger and Derrida had it, words can be used sous rature — i.e., “under erasure”.) On the other hand, even though some writers use scare quotes, that doesn’t automatically mean that their words are meant to be taken ironically (or not to be taken seriously). In Penrose’s case, it can be argued that the scare quotes simply signify that he’s aware that words like “see” are controversial within this precise context. However, that doesn’t mean that Penrose believes that they’re unacceptable or that they’re in some sense, say, metaphorical. (In all the other places I’ve read Penrose use these words, he doesn’t use scare quotes.)

iii) Gödel, Turing, Penrose

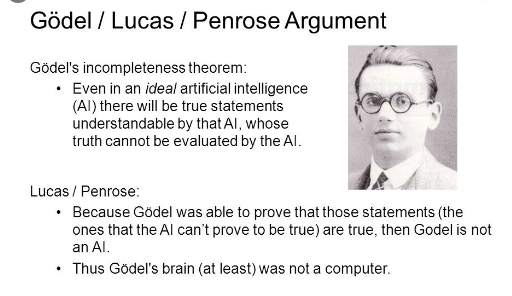

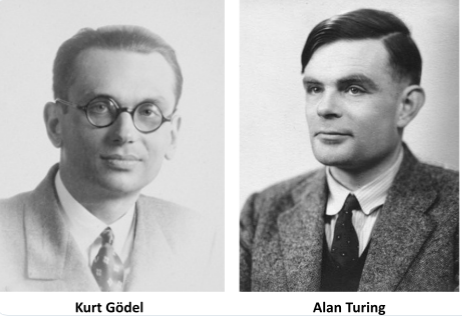

Of course this philosophical angle of Penrose is not all his own invention. Far from it. Gödel himself made philosophical comments about his own theorems. (This is to disregard the Gödel Industry; which applies his theorems to everything under the sun.)

In his ‘What is Cantor’s Continuum Problem’ of 1947, for example, Gödel explicitly made something (or much) of the fact that there’s a way of contacting “reality” other than through “sense perception”. (That said, even empiricists have acknowledged this; if with many additional clauses.) More precisely, Gödel used the words “mathematical intuition” to account for our (as it were) Platonic receptor.

So Alan Turing is a good counterweight to bring in here.

Although Turing accepted Gödel’s theorems, he didn’t also accept some of the things which were said to be consequences of those theorems. (Many see Turing’s Halting problem as the “computational equivalent” of Gödel’s first incompleteness theorem.) More specifically, Turing accepted that what Gödel called “intuition” is used in order to see the truth of a formally unprovable Gödel sentence. What he didn’t accept was that the brain and mind go beyond the “mechanical”. That is, Turing might well have asked Gödel how it is possible that non-mechanical intuition is carried out by a physically-embodied brain. (See Turing’s ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ — 1950 — for a very clear account of Gödel’s theorems and why Turing believed that they’d been somewhat overstretched.)

One other argument Turing offered was that because the brain is so complex, it simply appears to transcend its mechanical (or rule-following) nature. He also argued that (what he called) “initiative” doesn’t require uncomputable steps. (See Andrew Hodges’ ‘The Logical and the Physical’.) However, a machine’s (or computer’s) computations could still go beyond any programmer’s programme. (See also Turing’s “randomizer”.)

All this meant that Turing didn’t conclude (i.e., from Gödel’s theorems) what Penrose later came to conclude about the human mind or consciousness. And it also meant that Turing was happy with the idea of what later came to be called (firstly in 1956) “artificial intelligence”.

iv) Beyond Mathematical Platonism?

Despite the restricted scope (i.e., mathematics) of what has been said above, Penrose also seems to go beyond purely mathematical Platonism when he stated the following:

“[I] find words almost useless for mathematical [Penrose’s italics] thinking. Other kinds of thinking, perhaps such as philosophizing, seem to be much better suited to verbal expression. Perhaps this is why so many philosophers seem to be of the opinion that language is essential for intelligent or conscious thought!”

Like Plato, Penrose appears to glory in this escape from contingency. In this case, it’s the contingency of “words” and (no doubt) their lack of precision that must be escaped from… Or at least this is the case when it comes to mathematics.

Yet language, surely, is essential for Platonists too. That is, in order to become the Platonists that they are, language itself must have led their way in most/all of their philosophical directions. Indeed that’s even the case when it comes to mathematics.

Here again we also need to get our heads around what Penrose means by the word “visually”. It can be argued that Penrose would never have adopted and used these non-linguistic “concepts” if they weren’t first described to him in “words”. Sure, as with the a priori, we need to learn what the a priori is — and also to learn the words used in a priori statements — in order to have a priori “thoughts”. So this must mean that Penrose must be talking about what happens after the basic words and concepts are acquired. And what happens after is (he argues) something that’s completely non-verbal (or non-linguistic). So, yes, one has to know a posteriori what the words and symbols in the equation 2 + 2 = 4 mean. However, after that, the non-linguistic status of this truth remains unchanged.

As has just been stated about the a priori: we firstly need to learn the terms involved in this debate. However, once Penrose and other Platonists have acquired these words and symbols from a natural language, then perhaps they can “float free of the moorings” (to quote Kant on Plato) and rise into the Platonic realm.

v) Seeing Truths

So Roger Penrose often uses the words “see”, “seen” and “visualised” when it comes to certain mathematical truths (as well as, perhaps, other things). That is, he believes that many mathematical truths are seen to be true without being proved to be true. (In that simple sense at least, he’s simply putting Gödel’s position.)

Along with “seen”, Penrose also uses the words “insight” and “intuition”. For example he writes:

“[A] specific Gödel proposition — neither provable not disprovable using the axioms and rules of the formal system under consideration — is clearly seen [Penrose’s italics], using our insights into the meanings of the operations in question, to be a true [ditto] proposition!”

A useful and indeed apt technical term which captures Penrose’s claims is Paul Boghossian’s “flash-grasping”. The American philosopher defines his own term in the following way:

“Flash-Grasping: We grasp the meaning of, say, ‘not’ in a flash — prior to, and independently of, deciding which of the sentences involving ‘not’ are true.”

It may well be unfair to apply claims about the epistemology of logical terms (such as “not”, “and”, “or”, etc.) to what Penrose claims about certain mathematical truths. We’ll see later whether it’s possible to glide smoothly over from this area (as well as with the epistemology of the a priori) to Penrose’s seeing of mathematical truths.

Of course Penrose isn’t the only one to use words like “see” in the context of mathematical truths. For example, in the specific case of number theory and the Gödel sentence, G, the philosopher of logic Alasdair Urquhart uses the word “perception” (although it too is in scare quotes) in the following:

“Since we do seem to have a ‘clear and distinct perception’ of the notion of truth in number theory, it has often been argued that this demonstrates a clear superiority of humans over machines.”

And in the following paragraph Urquhart continues:

“[We], standing outside the formal system, and using our mathematical insight, can see that the sentence G is true, and so we can surpass the capacity of any fixed machine.”

However, in the above it can be said that Urquhart is (at least in part) putting other people’s positions. And since I’ve just quoted Urquhart, it’s also interesting that he questions Penrose’s claim that he can see that a Gödel sentence is true. He writes:

“The problem with the Lucas/Penrose argument … is that the key premise asserting that we can see the Gödel sentence to be true, remains undemonstrated. In fact, there are good reasons for thinking it to be false.”

In addition to the above, it also needs to be said that people may disagree as to exactly what it is they see. That is, one person may (platonically) see that p is true and another person may see that (the same) p is false. So even if we accept that there is Platonic seeing in both cases, that seeing alone doesn’t — and can’t — guarantee truth (or “truth without proof”).

So what about Penrose himself?

What does Penrose mean by “seen” here? Does he simply mean understand? Is it that we see the “meanings of the operations” simply because we understand them? That said, Penrose also stresses the fact that he “visualises” these things. So do people visualise meanings?

Of course all this may boil down to the simple fact that Penrose isn’t using the word “see” literally. (I mentioned scare quotes earlier.) Yet that still raises two questions:

1) Why does Penrose use the word “see”?

2) What does he mean by “see”?

Penrose also uses the word “sensing”. (Don’t we also sense when we see?) In this instance, Penrose goes beyond seeing the truth of a Gödel sentence and starts using much more modal and clearly Platonic ways of speaking. Indeed he partly explains what he means by “seeing” here:

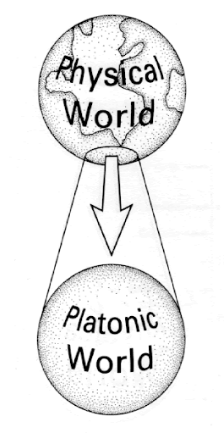

“[]I believe consciousness to be closely associated with the sensing of necessary truths — and thereby achieving a direct contact with Plato’s world of mathematical concepts.”

There is a reason (at least within this specific context) why Penrose stresses Platonic sight. As stated in the introduction, it’s because he believes that “[sensing necessary truths] is not an algorithmic procedure”.

vi) Do Platonic Truths Stand Alone?

In terms of looking at things epistemologically again, is it the case that Penrose sees Platonic truths because they “derive their evidence from themselves” (as Laurence BonJour puts it about a priori claims — see later)? In other words, is the proposition/equation/sentence itself all that’s required and nothing more? Yet surely this doesn’t work in terms of a mathematical theorems and especially not for a Gödel sentence. That’s because such things come at the end of a lot of reasoning, deductions, inferences, etc. which involve other propositions/equations/axioms/etc.

So it should be said (in strict accordance with the Penrose quote above) that what is seen is not, for example, the truth of Gödel sentence (G) itself. Instead, Penrose tells us that “the meanings of the operations in question” are seen. That is, firstly the meanings of the operations are seen, and only then does that lead to also seeing the truth of the Gödel sentence.

However, it can also be said that the truth of sentence G is seen precisely because the meanings of the operations (which led to it) were also seen. (Basically, if you see x, then you must also see y.)

One way of looking at this is the distinction made by philosophers between “relative” and “absolute” truths (or, more often, relative and absolute modalities) as found in logical deduction.

Absolute truths are true in and of themselves (as in an a priori or analytic manner, which will be discussed later). Relative truths, on the other hand, are a consequence of a previous set of axioms/statements/theorems/etc. Thus if the truths which Penrose can see are merely relative truths (in this strict logical sense), then how can we make sense of seeing within this relative context? That is, what is it to see truth T if T is actually a consequence of a further set of axioms/statements/theorems/etc. which may also be taken to be true (though not necessarily — they can simply be taken as given)?

This must mean that such theorems don’t have the same status as so-called analytic truths, such as:

All married men are bachelors.

Sure, you need to know the meaning of the terms and the fact that “married men” and “bachelors” are synonyms. But apart from that, there are no explicit (though they may be tacit) processes which lead towards one’s knowledge that the statement above is true.

So what about this? -

2 + 3 = 5

Laurence BonJour (more of whom later) says that the truth of the above is “guaranteed by its content”. That means that “understanding the proposition is a sufficient condition for recognising its truth”. Basically, as BonJour adds, this proposition is not “made true by experience”; but only “by content alone”.

vii) Penrose’s Rationalism

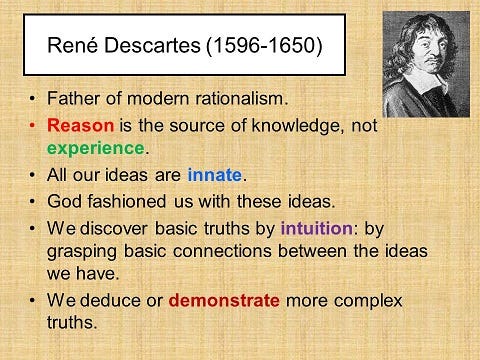

In many respects it would be just as accurate to classify Penrose as a rationalist (if with qualifications) as it would be to class himself as a Platonist. (Of course Platonism is a kind of rationalism.) And Penrose’s positions have a very rationalist feel to them. Indeed we can see similarities between Penrose’s position and statements found in Rene Descartes’ work — who was himself a rationalist.

So here’s Descartes himself putting his classic rationalist position:

“[I]f it could ever happen that a thing which I conceived so clearly and distinctly could be false… I can establish as a general rule that all things which I perceive very clearly and very distinctly are true.”

And elsewhere Descartes also writes:

“Clear and distinct perceptions are so coercive in their effect upon the mind that the mind cannot help assenting to them as true at the time it has such perceptions.”

It needs hardly be said that Descartes uses the words “perceive” and “perceptions” in the above. That is, he perceived certain truths. But to be fair (if that’s the right word) to Penrose, Descartes wasn’t talking about mathematical truths in the above. He was primarily talking about “the thing which thinks”. And, elsewhere, Descartes claimed to have “clearly and distinctly” perceived truths about God, the possibility of the mind existing without the body and suchlike. Penrose, of course, has never really ventured into any of these areas. (He has classed himself as an “atheist”.)

In addition to all that, it’s very clear that Penrose can’t be a strict (or complete) rationalist for the simple reason that he places a lot of emphasis on observations, scientific experiments, predictions, etc. Penrose even comes close to accusing string theorists of being Platonists in his Road to Reality and his most recent book Fashion, Faith and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe. He does so because such string theorists appear to have a complete trust in their “consistent” and purely mathematical theories — theories which aren’t backed up by (unique) experiments or predictions.

Yes; Penrose is also a mathematical physicist. Then again, Descartes (along with Leibniz and Spinoza) too had a great respect for science and experiment and indeed his rationalist work was seen (by himself) to be but a means of securing the science of his day.

viii) Laurence BonJour: A Rationalist of the 21st Century

Let’s bring things more up to date and move beyond Plato, Descartes and other dead rationalists. Take the American philosopher Laurence BonJour.

BonJour’s rationalism is encapsulated in his position on the a priori. The following is what he says on that subject:

“[I]f we never have a priori reasons for thinking that if one claim or set of claims is true, some further claim must be true as well, then there is simply nothing that genuinely cogent reasoning could consist in. In this was, I suggest, the rejection of a priori reasons is tantamount to intellectual suicide.”

As it is, BonJour describes himself as a “rationalist”. And, clearly, he’s also well aware of the criticisms of rationalism. For example, in reply to the Australian philosopher Michael Devitt, Bonjour talks of Devitt’s

“allegations that rationalism is ‘objectionably mysterious, perhaps even somehow occult’…”

He concludes by saying that he find these allegations “very hard to take seriously”.

So what else does Devitt have to say on BonJour? The following:

“BonJour is an unabashed old-fashioned rationalist (apart from embracing the fallibility of a priori claims). He rests a priori justification on ‘rational insight’: ‘a priori justification occurs when the mind directly or intuitively sees or grasps or apprehends… a necessary fact about the nature or structure of reality’…”

Sure, it may not be such a good thing to quote Philosopher X on Philosopher Y — especially if they take diametrically opposed positions on the same issue. In any case, there are certain elements in the passages above that don’t entirely square with Penrose’s own positions.

For example, how strong and clear is Penrose himself on the “fallibility” of his seeings of mathematical truth? (Note: If BonJour accepts the possibility of a priori fallibility, then what about the possibility that all a priori claims are fallible and/or indeed false?)

In addition, are Penrose’s claims necessarily applicable to “the nature or structure of reality”? Or are they simply about mathematics/mathematical systems? Yes, it’s true that mathematics must be part of reality; though many of BonJour’s a priori claims are literally about the physical world itself.

So what does BonJour’s rationalism amount to? Take the following passage:

“[A]n intuition is a semi-cognitive or quasi-cognitive state, which resembles a belief in its capacity to confer justification, while differing from a belief in not requiring justification itself.”

And elsewhere:

“[I]n the most basic cases such reasons result from direct or immediate insight into the truth, indeed the necessary truth, of the relevant claim.”

So, like Penrose, BonJour uses the phrase “necessary truth”. That is, BonJour ties necessity to truth. Again, in BonJour’s own words:

“Devitt seems to me to be simply rejecting the idea that merely finding something to be intuitively necessary can ever constitute in itself a reason for thinking it is true…”

Indeed BonJour goes further by stating the following:

“[A priori] insights at least purport to reveal not just that the claim is or must be true but also, at some level, why this is and indeed must be so. They are thus putative insights into the essential nature of things or situations of the relevant kind, into the way that reality in the respect in question must be.”

There’s just been a lot of focus on the epistemology of seeing truth. So here’s another problem from epistemology on a priori (if not Platonic) seeing from the American philosopher James Van Cleve. He writes:

“If the foundationalist claims that his principles are immediately justified, then what it to prevent, let us say, a [religious] revelationist from claiming the same status for a principle to the effect that if S has an ostensible revelation that P, then S is justified in believing that P?”

(Of course it doesn’t help us much when Van Cleve concludes by saying that “[s]ome claims to immediate justification are spurious”. After all, as stated earlier in regards to a priori “fallibility”, if some cases of “immediate justification” are “spurious”, then perhaps all of them are.)

The question now is:

How applicable is all the above to Penrose’s own seeings of mathematical truths?

ix) Conclusion: Is Roger Penrose Really a Platonist?

It can be argued (or seen) that Roger Penrose doesn’t really extend his Platonic vision much (or at all) beyond mathematics. Having said that, his strong and controversial positions on consciousness and artificial intelligence can indeed be seen to be going beyond the mathematics. Nonetheless, Penrose would no doubt argue that these positions are largely (or even wholly) derived from the maths.

It’s often said that the general “Platonic position” on mathematics is the “consensus position” among mathematicians — and indeed among many other people outside mathematics. However, it must also be said here that most mathematicians don’t philosophise in this way about their own subject. (Though some mathematicians most certainly do.) In addition, the acceptance of Gödel’s theorems is almost universal. So too is the notion of mathematical intuition. (Here again it must be said that not many mathematicians will use these terms.) So it’s when Penrose extrapolates from these Platonic and Gödelian positions that he loses the consensus. For example, not many scientists or philosophers accept his very particular take on consciousness. And as for his stance against (strong) artificial intelligence, that too has received a large amount of criticism from many different quarters.

And from a strictly philosophical (or epistemological) point of view, Platonic seeing comes up against many hurdles; many of which (as discussed above) have been applied to the positive (rationalist) positions on the a priori in epistemology. In addition, cognitive scientists (of various kinds) will also have many things to say about Platonic seeing.

Yet, despite all that, it’s still the case that many people’s intuitive (as it were) position on mathematical intuition will be to claim that we do indeed immediately and (platonically) see the truth of, say, the equation 2 + 2 = 4. But where does that possibility (or reality) take us?

Finally, it can be said that Roger Penrose can indeed be seen as a rationalist — but only in very limited respects (i.e., when it comes to his position on mathematics). Yet if Penrose is a rationalist only in such limited respects, then how can he be a rationalist at all? In other words, were Plato, Descartes, Leibniz and Spinoza rationalists only in limited respects? And, as a further consequence of this, can it also be said that Penrose is a Platonist only in limited respects? After all, Plato himself wasn’t a Platonist only in limited respects.