The title of this essay could just as easily have included the words “poststructuralists” and “postmodernists”. However, it would have been too long had I done so.

“[T]he nature and significance of Heidegger’s thought cannot be determined by selective quotation from his work nor by a focus on the shortcomings of Heidegger the man. If it is his philosophy that is at stake here, then it is with his philosophy that we must engage — and there are no shortcuts to doing that.”

— The philosopher Jeff Malpas (as quoted by Jonathan Este). [See note 1.]

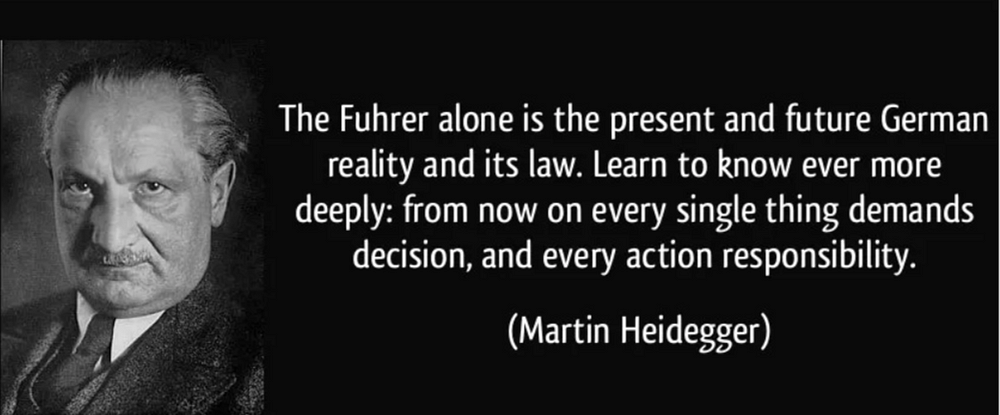

“Heidegger’s support for the Nazis is well known and has been meticulously documented. Six years after publication of Being and Time, Heidegger joined the NSDAP and was elected rector at the University of Freiburg in 1933. In that role he gave a number of speeches in support of the new regime and wrote denunciatory letters about liberal and left-leaning colleagues.”

— Jonathan Este

More relevantly, the journalist and writer Jonathan Este then continued:

“The inevitable question is whether Heidegger’s Nazism infected his philosophy.”

Transcending Rationality

The following are two problems with those individuals and groups who and which want to “transcend rationality” (or to “transcend reason”):

(1) Historically, reason has often been required (or used) in order to transcend reason.

(2) Those individuals and groups who and which extol transcending reason have also needed to compete with rival individuals and groups who and which also extol transcending reason.

In terms of (1). Since irrationalists have (supposedly?) given up on reason or rationality, then they must use violence, abuse, emotional language, poetic/categorical proclamations, etc. instead (i.e., in order to impact on society at large).

It’s true that reason needn’t always be required to transcend reason. However, this has usually been the case. Of course, tapping into people’s feelings and emotions has been a very popular means of transcending reason…

That said, not all those who ride on people’s feelings and emotions will also claim to be “transcending reason”. Thus, this is a very philosophical way of putting the issue.

It also gets more complicated because many of those who tap into people’s feelings and emotions can’t exclusively do this via irrational means. Indeed, they too must use their reasoning skills.

Think here of the parallel case of those Nazis, Heideggerians and religious people (such as Creationists and New Agers) who’ve castigated science at the very same time as making full use of scientific technology…

How could it be otherwise?

Heideggerians have just been mentioned.

So is the enterprise of “transcending reason” one explanation as to why Martin Heidegger embraced the Nazis?

Heidegger: An Anti-Intellectual Intellectual

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger is a good case study here.

Heidegger was a very intellectual anti-intellectual.

Firstly, some (perhaps even many) Heideggerians would argue that Heidegger used reason against reason. (As did Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason.)

… Actually, this last claim is debatable.

As just stated, some Heideggerians are keen to stress Heidegger’s actual arguments (i.e., even if those arguments need to be suitably parsed). Other Heideggerians, on the other hand, really do want to emphasise the fact that Heidegger “transcended reason and rationality” in order to escape into some kind of poetic, mystical and intuitive… something — “I know not what”.

Of course, these two attitudes to Heidegger's philosophy may well be held together.

In any case, the German National Socialists (i.e., of the 1920s, 1930s and early 1940s) wanted to transcend reason/rationality too.

And Heidegger has been frequently and strongly connected to the Nazis.

Most Heideggerians, of course, say that this Nazi connection is irrelevant to Heidegger’s actual philosophy…

Really?

What if Nazi and other other kinds of irrationalism are deeply embedded in Heidegger’s philosophy?

Thus, the similarities between Heidegger’s philosophy (or philosophies) and Nazism include the following:

an interest in mysticism and the early medieval period (shared with, amongst others, the English Catholic fascists of the early 20th century), anti-intellectualism (or intellectual anti-intellectualism, as with Joseph Goebbels), a distaste for modern civilisation, science and technology (which can quite easily go alongside the use of technology, as was the case with the Nazis), counter-Enlightenment positions, a stress on “thinking with the blood”, an idealisation of peasant life, and so on.

So it’s odd that many Heideggerians are keen to play down Heidegger's explicit politics at the very same that they’re keen to play up other philosophers’ implicit politics.

The reason for this is fairly simple.

Heidegger’s philosophy is often used to advance somewhat fashionable political views and positions. Thus, they claim that his political beliefs and actions in favour of the Nazis and Nazi policy muddy the philosophical water. They also claim (as Jeff Malpas does in the opening quote) that Heidegger’s philosophies stand regardless of his connections to Nazism.

On the other hand, other philosophers often have their political lives gone over with a fine tooth comb — sometimes by these very same Heideggerians! Obviously, this is the case because of the specific nature of their politics.

So there are double standards here. [See note 1.]

To repeat.

It really does seem bizarre that Heideggerians are at pains to play down Heidegger’s Nazi connections. Indeed, this was precisely what the French philosopher Jacques Derrida did.

That last claim has been fiercely disputed.

The broad upshot is that, of course, Derrida didn't deny (or ignore) Heidegger’s Nazi connections. However, he did attempt to separate them from Heidegger’s actual philosophy… Or at least Derrida attempted to separate such Nazi connections from Heidegger’s later non- “metaphysical” philosophy. [See note 2.]

Heidegger’s Nazi Philosophy

As just alluded to, and despite the defences of Heidegger, many people have noted the strong similarities between, just to take one example, Heidegger’s philosophical “attacks on realism” and Nazism. Indeed, there are many other connections between Heidegger and Nazism that are worth commenting upon. And that’s for the simple reason that they also have a bearing on Heidegger’s actual philosophical positions, beliefs and attitudes.

More specifically, if there is any direct connection to be found between Heidegger and Nazism, it’s that of anti-intellectualism.

Oddly, Heidegger’s anti-intellectualism is very intellectual in form.

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that this anti-intellectual intellectual had strong sympathies with German National Socialist forms of anti-intellectualism.

Now let’s connect anti-intellectualism to the parallel desire to transcend reason.

It’s worth quoting Jonathan Estee again here. Este writes:

“[A]t one point [Heidegger] speaks of the characteristically Jewish gift for ‘calculation’, which would then find an ideal foothold in ‘the empty rationality and calculative bent’ of Western metaphysics, especially since Descartes.”

This negative attitude toward “calculation” and “empty rationality” can also be found all over the place in the writings of fascists, Nazis, New Agers, spiritual people, postmodernists, poststructuralists, etc.

Heidegger on the Flight of the Gods

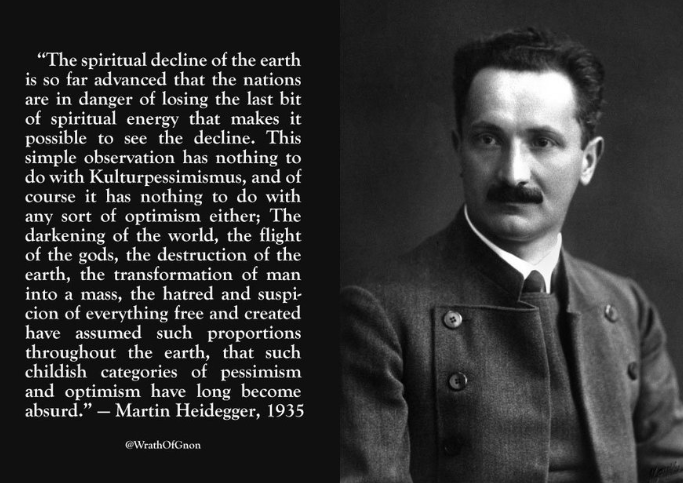

Martin Heidegger once wrote of the “flight of the gods”.

This was a reference to what he took to be the ascendancy of “scientific culture” in 20th century Western society (including Germany, most of Europe and the United States), as well as the concomitant rise of what’s often called “instrumental rationality”.

(Heidegger — along with Edmund Husserl — also wrote of the scientific flight from “lifeworlds”.)

In his Being and Time, Heidegger had the following to say about “the world” as it was in the late 1920s:

“We have said that the world is darkening. [] [T]he flight of the gods, the destruction of the earth, the standardization of man, the pre-eminence of the mediocre.”

Heidegger also told his readers that “we are too late for the gods, and too early for Being”.

Heidegger believed that Europeans were too late for the gods because theology and metaphysics themselves could no longer have any purchase on the modern mind — even way back in the 1920s! Unfortunately, most Europeans (at the time) were also “too early for Being”. That is, they were too early for Heidegger’s very own ontotheology (or ontic-theology).

Now let’s consider Heidegger’s well-known hammer example.

The Hammer, and the Ontology of the Social

Heidegger’s general point was that (in everyday life) we don’t have intellectual knowledge of the hammer we use to bang in nails. Instead, we have some kind of (for want of a better word) intuitive relation to the hammer. In other words, we don’t really know that the hammer is too heavy. Instead, the hammer “reveals itself as being too heavy”. That means that we only have a physical relation to the hammer, not a knowledge-based one. In fact, Heidegger seems to claim that when we use a hammer, we don’t think at all. We simply feel that it’s too heavy.

Of course, this somewhat innocuous(!) hammer example can be — and indeed has been — broadened out by Heidegger and others.

Thus, we come to to Heideggerian “involvement” and Heideggerian action.

Heidegger believed that knowledge must be firmly connected (in some way) to action. Or, in Heidegger’s own words, it must be connected with our “concern” for the world.

Yet perhaps Heidegger was right to argue that knowledge is “secondary to [our] involvement in the world”. Indeed, isn’t it the case that we wouldn’t even care about knowledge if it weren’t for the fact that we’re somehow already involved with the world? In other words, without some kind of involvement, the desire for knowledge wouldn’t even arise in the first place.

(These aspects of Heidegger’s philosophy, alongside “the ontology of the social”, appeal to Left Heideggerians.)

So what about Heidegger's mysticism?

Heidegger on Spiritual Dasein

Master Eckhart (1260 — c. 1327) is generally regarded as the greatest representative of German mysticism. This mystic had a strong impact on the young Heidegger. More particularly, it was Eckhart’s notion of not knowing anything that inspired Heidegger.

It can be noted here that Heidegger also put this “question of Being” forward as the “spiritualising” part of the National Socialist revolution in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In any case, Master Eckhart himself once wrote the following words:

“[W]e say that a man ought to be empty of his own knowledge, as he was when he did not exist.”

Heidegger opposed (what he took to be) traditional metaphysics with his very own “meditative” alternative. At times, he called this meditative alternative “thinking” or “letting be”, which was a term he adopted from Meister Eckhart.

Heidegger also used the German word Gelassenheit.

This is a term for thinking “without [a] why”. According to Heidegger (at least at one point in his career), meditative thinking “lets things” show themselves, rather than be shown (or circumscribed) by the inquiring mind.

The mystic German Catholic priest Angelus Silesius also influenced Heidegger. Indeed, it is “Silesius’s rose” that, according to Heidegger, lives “without reason” or “without why”. [See here, and note 3.]

Heidegger’s most important concept, Dasein, also has a mystical (or religious) dimension to it.

Dasein is “to be” in the world.

Heidegger believed that his notion of Dasein is not one of knowing. Instead, Dasein is always already in the “background” each time we know, acquire knowledge, or contemplate the world. [Interestingly enough, the American analytic philosopher John Searle has made extensive use his own notion of “the Background”.]

In a basic sense, then, all the above appears to stress the non-rational or non-intellectual nature of Dasein. In other words, the overall aim is to be, rather than to think. In addition, action and involvement (or “changing the world”) was also very important to Heidegger, as it still is to contemporary Heideggerians.

Notes:

(1) This passage from Malpas is taking the only-engage-with-the-philosophy-itself idea to its extremes. And some readers will doubt that Malpas himself is ever entirely faithful to his own impossible — and perhaps even counterproductive — ideal.

What’s more, my argument in the essay above is that Heidegger is a very bad choice when it comes to abiding by Malpas’s philosophical ideal. In fact, there’s something a little phony (or even dishonest) about it when applied to — specifically — Heidegger!

(2) Derrida once criticised philosophers for erasing their private lives from their philosophies. See ‘Derrida: On The Private Lives of Philosophers’. here. See also ‘Derrida and the Heidegger Controversy’, and ‘Everything Burns: Derrida’s Holocaust’.

No comments:

Post a Comment