Should Science Shape Society in Very Specific Political Ways?

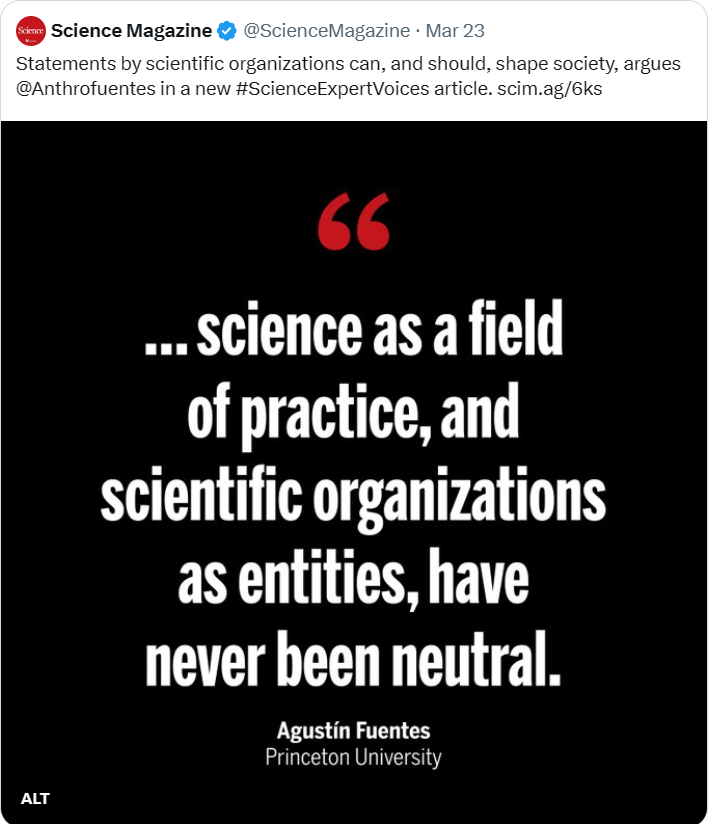

This is certainly the position adopted by Scientific American in recent years, and even more obviously by Science Magazine (or Science).

When it comes to Scientific American, it’s fairly new editor — Laura Helmuth (she also edited Science Magazine!) — has explicitly said that it should be politically committed in specific political ways (see here). This led to an entire edition being devoted to political issues. [See also Scientific American’s ‘Yes, Science is Political’, and Scientific American dedicates itself to politics, not science’.]

The problem with those scientists, activists and laypersons who say that “science shouldn’t be neutral” is that they usually have something very specific in mind. That is, they believe that “science as a field” should be politically committed and politically aware. More importantly, it should be committed to specific political things, and be aware of specific political things…

But what happens when other scientists take views the activists strongly disagree with?

What happens when other scientists and activists become committed to political and social causes they find very objectionable?

Thus, the self-conscious attempt to politicise science can actually backfire — at least it can do so for these activists.

The upshot, again, is that those who say that science “should shape society” have very specific political and social things in mind. So this isn’t an abstract statement about science and its (obvious) relation to society as a whole. This is a manifesto from specific political activists (some of whom are scientists) with specific political ends and goals in mind.

Thus, they’ll also need to do battle with those scientists who uphold different political views. This, then, will become like a battle for Gramscian hegemony. It just happens that it will be a battle fought by scientists against other scientists.

The Science Magazine and Scientific American position also turns science into a political weapon that scientists and activists use to advance political causes and ends.

Of course, this already occurs at Science Magazine and Scientific American. But, it seems, the activists want more control and power over the entire scientific enterprise.

Is that a positive scenario?

A Flawed Philosopher?

Kevin M (i.e., associate professor of philosophy Kevin Morris) seems to overlook the possibility that a “non-philosopher” may simply be bored by the aspect of philosophy being discussed at the time. After all, nearly all (professional) philosophers themselves will be bored by certain areas of philosophy. In other words, no philosopher finds all philosophy interesting or worth discussing.

So mentioning boredom isn’t condescending to laypersons, or a slap in the face of philosophy itself. Basically, you simply can’t generalise about non-philosophers and philosophers in these scenarios.

For example, if someone talks to me about computer programming or even theoretical biology, this would probably bore me. But that has no large implications for the theoretical biologist/computer programmer, or for me as a layperson…

There simply aren’t enough hours in the day.

By the way, what is a “deep philosophical conversation”? More specifically, what’s meant by the word “deep” here?

Interdisciplinary Philosophy

I too believe that “philosophical work in mind and language” is superior when it consults the various relevant sciences. And, sure, that’s happening more nowadays than it did in the past — at least when it comes to mind and language. That said, I’ve read some works on mind and language by philosophers that are just examples of science.

I believe that Patricia Churchland is a good example of this. (Most of the stuff I’ve seen of Churchland’s is just neuroscience, cogntive science, etc. — for good or bad.)

But I’ve seen other lesser names who write papers, etc. with virtually no philosophy in them. Instead, they’re simply either accounts of the scientific literature on the given subject, or even purely scientific themselves.

Perhaps the partisans of science-vs-philosophy like this result in philosophy.

Climate and Groups: Science and Politics

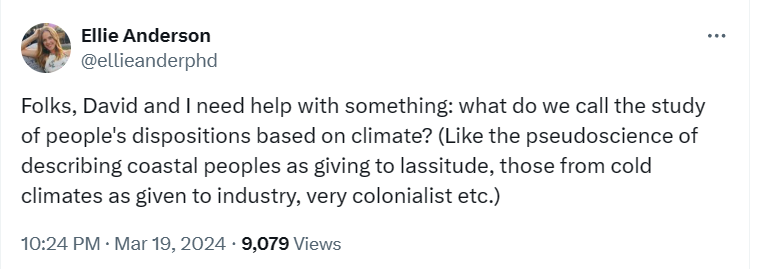

Climate must have at least some impact on human groups as taken in broad terms, and over longish periods. Of course, we’d need to be careful about generalisations and speculations. However, doesn’t Professor Ellie Anderson (@ Pomona College) herself generalise about all those who’ve simply noted the impact of climate on the behaviour of certain groups throughout history?

It depends on what she means by “people’s dispositions” too.

Are we talking about individuals’ beliefs and collective beliefs too, or just non-verbal behaviour? Indeed, can we disentangle the two at all?

Ellie Anderson is trying soooooo hard not to be racist — and also to be anti- “colonialist” (her word) — that she’ll overlook all contradictory evidence.

And she’s also keen to use the term “pseudoscience”, which is often used as a political sledgehammer.

Anderson’s main aim is no doubt political, not scientific or philosophical. And this is exactly how she seems to read the views — on this subject at least — of her scientific and philosophical opponents…

Is this a case of projection in the battle for political hegemony?

Hollywood Zombies and Philosophical Zombies

Spoiler alert: the notion of a zombie in analytic philosophy is very unlike the notion of a zombie in Haitian voodoo or in Hollywood films. Hence the term “philosophical zombie” (or “p-zombie”).

The main difference is that you could behaviourally and visually spot Hollywood zombies from a mile away. You couldn’t do that with an “analytic” p-zombie. Indeed, that’s precisely the point of this philosophical notion.

All that said, this tweeter appears to classing analytic philosophers themselves as zombies!

Wittgenstein’s Philosophical I

I take Wittgenstein’s point… to a degree. However, the (errr) “fact” that each subject both cognises and experiences almost everything of “the world” through the prism of the “philosophical I” doesn’t — automatically — mean that it is “not a part of the world”. (No philosophical account of the “I” needs to be given or accepted here.)

A more mundane analogy here is the inability to literally look at your own eyes… with your own eyes. (I.e., without the help of a mirror, photograph, etc.) There is nothing “metaphysical” about this example… at least.

The Cartesian self (if there is such a thing) is also part of the world. What else can the Wittgenstein I or the Cartesian subject be a part of?

No comments:

Post a Comment