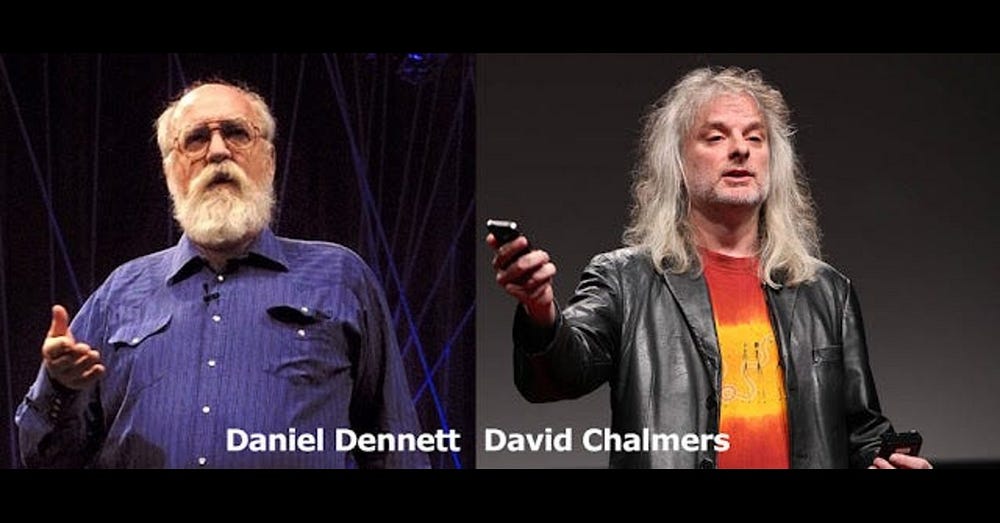

Some readers may believe that it’s a little conceited (or at least needlessly autobiographical) to refer back to — and even quote from — my ‘Chalmers’ Naturalistic Dualism vs Dennett’s Third-Person Absolutism’. However, my previous stance on Daniel Dennett’s “third-person absolutism”, alongside my revised stance on the same subject, may be informative. After all, reading both a critical and a positive stance on the same position is always helpful in philosophy. Thus, reading both critical and positive stance on the same position from the very same person — if at different times — may be helpful too.

It doesn’t help (or perhaps it does) that the American philosopher Daniel Dennett once referred to his own position as “third-person absolutism”. [Did Dennett actually use these words? See note 1.] That said, wouldn’t a genuine absolutist stay well clear away from advertising the fact that he is one? In other words, perhaps Dennett was simply being ironic and rhetorical when he used that self-description… Sure, perhaps he was being serious too.

Consciousness Explained Away?

Many philosophers and commentators have been very keen to tell us — and they’ve done so many times — that Dennett’s book Consciousness Explained should really have been called ‘Consciousness Explained Away’ or ‘Consciousness Ignored’.

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers didn’t go that far. However, he did say that what he calls “type-A materialists” (see here) believe that

“there is not even a distinct question of consciousness: once we know about the functions that a system performs, we thereby know everything interesting there is to know”.

According to Chalmers, then, Dennett fits the description above.

Yet when you read Dennett (at least in different passages and at different times), he doesn’t deny consciousness at all. Instead, he simply has his own particular take on it.

Of course, to some (even many) people, Dennett’s particular take does still explain consciousness away.

The American philosopher John Searle, for example, had the following to say on this matter:

“To put it as clearly as I can: in his book, Consciousness Explained, Dennett denies the existence of consciousness. He continues to use the word, but he means something different by it. For him, it refers only to third-person phenomena, not to the first-person conscious feelings and experiences we all have.”

As stated, Chalmers (perhaps unlike Searle) doesn’t state that Dennett denies consciousness outright. Instead, he tells us that Dennett believes that the sum of mind-brain functions, behaviour, “verbal reports” (see here), etc. are what constitute consciousness.

In Chalmers’s own words, when it comes to Dennett’s position,

“there is no interesting fact about the mind, conceptually distinct from the functional facts, that needs to be accommodated in our theories”.

In a previous essay, I too had an absolutist take on the correct definition of the word “consciousness”. Alternatively, I had an absolutist take on what consciousness is. For example, I wrote:

“[I]sn’t [Dennett’s position] like someone saying that ‘God exists’, and then it turns out that what he means by the word ‘God’ is ‘The ghost who lives at the bottom of my garden’?”

So, according to some definitions of consciousness, it can be argued that Dennett would say that conscious does not exist. However, according to his own definition (as mentioned by Chalmers above), consciousness does exist.

Thus, perhaps we’re left with a situation in which consciousness exists according to some definitions of the word ‘consciousness’, but not others.

So now take those philosophers and laypeople who stress how things feel (or how things seem) and/or “fundamental and rudimentary” qualia. Most of these people would deem it ridiculous to say that definitions have anything to do with these matters…

But definitions — and the (technical) terms we use — do have a lot to do with the matter of consciousness.

After all, it’s not those (to use Philip Goff’s words) “private seemings” which are the problem, but what we say about them. More relevantly, it’s how we philosophise and theorise about them. Indeed, it’s also about how reading books about consciousness (or seeing the word “qualia” all the time) may influence what we say about consciousness. (Patricia Churchland once said that the word “‘qualia’ is a term of art, which was introduced by philosophers”.)

The English philosopher Philip Goff has also used the following statement a fair amount of times: “Consciousness is a datum in its own right.”

Now how does that “datum” stand within the context of all the books and papers Goff and others have read on the subject of consciousness? What’s more, can any distinction at all be made between such a (supposed?) datum and all the books (or theories) each philosopher and layperson has read about it?

So if (some) readers have read loads of books on consciousness (or read the word ‘qualia’ many times), then surely that will impact on how they describe and/or theorise about any ostensibly private seemings they may have. [See Paul Churchland’s position on a related theme in note 2.]

Chalmers on Dennett’s Third-Person Absolutism

My previous criticisms of Daniel Dennett’s third-person absolutism were perhaps a little too dependent on David Chalmers’ own. That said, I did have problems with Dennett’s positions before looking into what Chalmers — particularly — had to say on the matter.

Chalmers expressed Dennett’s functionalist absolutism by citing the following examples:

“[I]t is far from obvious that even all the items on Dennett’s list — ‘feelings of foreboding’, ‘fantasies’, ‘delight and dismay’ — are purely functional matters. [] One’s ‘ability to be moved to tears’ and ‘blithe disregard of perceptual details’ are striking phenomena, but they are far from the most obvious phenomena that I (at least) find when I introspect.”

One of my own responses to this passage from Chalmers was this:

“Prima facie, it does seem amazing that Dennett sees such things as solely functional matters.”

I then added the following words:

“[I]t’s hard to understand what it could mean to say that the ‘ability to be moved to tears’ is a purely functional matter. (What’s with the word ‘ability’?)”

Yet it now seems that it’s not that there aren’t any private seemings, but that we can’t do anything with them. That, in itself, isn’t to deny the seemings or the privacy. After all, if the reader thinks to himself a certain thought (say, that elephants are pink and eat marbles), then there’s no way that Dennett — or every scientist on the planet in a group effort— could guess what he or she is thinking. Thus, isn’t that particular thought private?

Chalmers also defined Dennett’s position as the view that “what is not externally verifiable cannot be real”.

It can be presumed that Chalmers was arguing that Dennett’s position is that there must be a fundamental (as well as theoretical) connection between any x being real (or existing), and whether or not we can externally verify it. On this reading of Dennett, then, if we can’t externally verify x, then it doesn’t exist. It’s not real.

Thus, perhaps the aforementioned thought about pink elephants isn’t real.

Yet one wonders if Dennett actually used the word “real” in this context.

Sure, he would have certainly emphasised external verifiability. However, the word “real” seems like Chalmers’ own personal addition.

As for Dennett’s own responses to Chalmers’ criticisms.

It’s not surprising that Dennett asked Chalmers (at least according to Chalmers himself)

“to provide ‘independent’ evidence (presumably behavioral or functional evidence) for the ‘postulation’ of experience”.

That passage neatly expresses Dennett’s (supposed?) third-person absolutism.

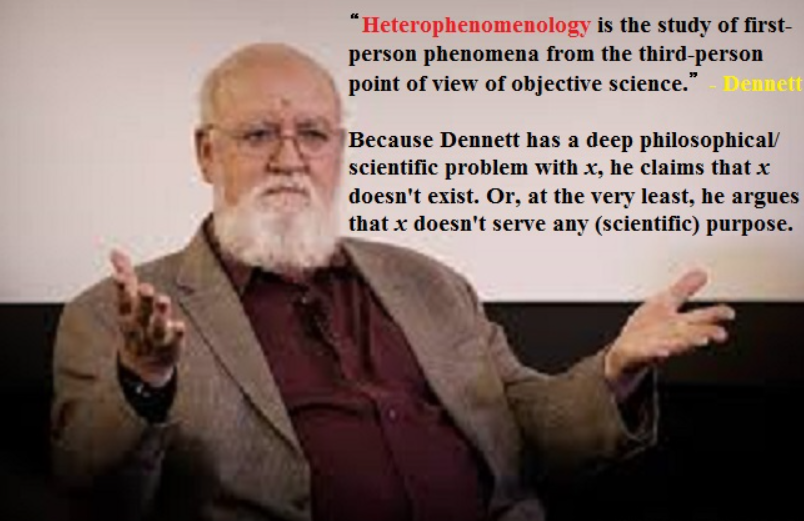

Such a position, according to Chalmers, allows and encourages “a third-person perspective on one’s first-person perspective”. (This is an articulation of Dennett’s heterophenomenology.)

Yet Dennett simply seems to be advancing a scientific position on the subject of consciousness…

So where is the absolutism in that?

After all, because Dennett is attempting to make the study of consciousness scientific, then, sure, we can go with Chalmers when he said that (in Dennett’s Consciousness Explained) “heterophenomenology” (like Quine’s position on “overt behaviour” when it came to meaning) is deemed to be “the central source of data”.

In a sense, it can’t be anything else but the main — or even only — source of data. Surely the alternative is taking the words about consciousness, qualia, etc. of all subjects to be gospel. Yet what if such subjects contradict each other on these matters?

Chalmers also tells us that

“the only ‘seemings’ that need explaining are dispositions to react and report”.

Again, this is Dennett’s attempt to make the subject of consciousness scientific.

That’s primarily because even though there are very many philosophical, (purely) phenomenological, and religious (or “spiritual”) accounts of consciousness, these accounts are still endlessly disputed, and of no help to scientists…

Still, Chalmers isn’t happy with Dennett’s position.

He tells us that it’s an “unargued assumption that such reports are all that need explaining”. In other words, Chalmers believes that some things over and above the “reports” also “need explaining”. These things include how things feel (or seem) to the subject, qualia (or phenomenal states), etc… whichever terms or phrases one uses.

All that said, eight years ago I wrote the following:

“[] if we follow the logic of Dennett’s behaviourism to its end, can we accept a first-person perspective at all? (That is, even if that perspective is accounted for in third-person terms.) In other words, is there a first-person perspective on anything in Dennett’s scientific book?”

I even became a bit personal with these words:

“Dennett’s language here is ringing with scientific clichés. He talks of ‘independent evidence’ and the ‘postulation of experience’.”

I also stated that “the idea that consciousness is ‘postulated’ is very strange”.

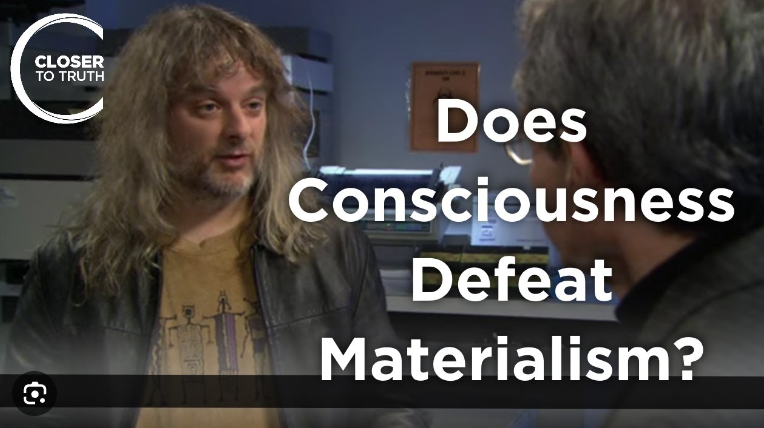

Conclusion: Chalmers’ Stance on Dennett’s Materialism

Chalmers argued (if sometimes implicitly) that Dennett stresses “verbal reports”, etc. because he wants to defend — or even save — what Chalmers calls “materialism”. Thus, Chalmers quoted Dennett saying that

“‘if something more than functions needs explaining, then materialism cannot explain it’”.

Chalmers also said that “the idea that function is all we have access to at the personal level [is] false”. In my other essay, I too wrote: “I would say: obviously false.”

In terms of materialism itself, Chalmers’ said the following:

“What’s controversial about my own view is not so much that I defend the existence of qualia, but that I argue that they are nonphysical.”

If consciousness is “nonphysical”, as Chalmers believes, then of course “materialism cannot explain it”. That’s true by definition.

Notes:

(1) In his paper ‘Moving Forward on the Problem of Consciousness’), David Chalmers claimed that Daniel Dennett used the words “third-person absolutism” about his own position. As it is, I couldn’t find Dennett himself stating these words. The only work by Dennett which Chalmers references (in the paper just mentioned) is ‘Facing Backwards on the Problem of Consciousness’ — and I couldn’t find it there either.

However, for the purpose of this essay, I still happily used the words “third-person absolutism” because they’re so convenient.

(2) The Canadian philosopher Paul Churchland once wrote the following:

“Given a deep and practiced familiarity with the developing idioms of cognitive neurobiology, we might learn to discriminate by introspection the coding vectors in our internal axonal pathways, the activation patterns across salient neural populations, and myriad other things besides.”

Of course, at present it would be (virtually?) impossible (even for a neuroscientist) to describe our (to use Churchland’s own words) “first-person” thoughts, feelings and beliefs in terms of “coding vectors in our internal axonal pathways”, “activation patters across salient neural populations”, etc. It may even be hard to imagine such a state of affairs at present.

Yet Churchland wasn’t talking about the case as it is today. That said, he did explicitly state that

“it is entirely possible for a person or culture to learn and use some other framework in that role”.

No comments:

Post a Comment