Bernardo Kastrup, Deepak Chopra and other idealists have attempted to initiate Werner Heisenberg into the idealist camp. Are they right to do so?

(i) Introduction

(ii) Heisenberg on 19th-Century Materialism

(iii) Heisenberg on Dialectical Materialism

iv) Heisenberg on Einstein’s Materialism and Realism

(v) Heisenberg on Positivism and Idealism

(vi) What is Materialism?

(vii) Materialism Through the Eyes of Contemporary Idealists

Almost all the quotes from Werner Heisenberg in the following essay are taken from his book Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science. This book began life as Heisenberg’s 1955–6 Gifford lectures at the University of St Andrews (Scotland). It was first published in book form in 1958.

Introduction

Idealists, anti-materialists, New Agers and mystics often quote and mention Werner Heisenberg to back up what they already believe anyway. In other words, when you look into this, it can quickly be seen that virtually no contemporary idealist became an idealist due to his research into quantum mechanics. Instead, what nearly always happened is that such people became idealists for exclusively philosophical and/or spiritual reasons - and only then did they look to quantum mechanics for scientific backup.

Take these words from the idealist Deepak Chopra:

“The possibility of a mental universe has a strong lineage going in the quantum era, but present-day physicalists (physicists who accept the physical nature of reality as a given) feel free to dismiss or ignore figures as towering as Max Planck, Werner Heisenberg, and John von Neumann.”

Now take these words from an idealist (see here) who believes that he has “proved” that heaven exists (as in his book, Proof of Heaven) — Dr Eben Alexander:

“We live in a mental universe, projected out of consciousness, just as Heisenberg realized [].”

Despite my use of the term “mystics” earlier, the idealist Bernardo Kastrup warns against such (critical or negative) readings of contemporary idealism. Kastrup writes:

“We are often misinterpreted — and misrepresented — as espousing solipsism or some form of ‘quantum mysticism,’ so let us be clear: our argument for a mental world does not entail or imply that the world is merely one’s own personal hallucination or act of imagination. Our view is entirely naturalistic: the mind that underlies the world is a transpersonal mind behaving according to natural laws. It comprises but far transcends any individual psyche.”

It can easily be seen here that Kastrup is merely jumping out of the frying pan into the fire.

That is, Kastrup believes that forsaking what used to be called subjective idealism (which many people have also seen as a kind of solipsism) to embrace what was once called objective idealism (now, in its updated form, often called either Universal Idealism or Cosmic Idealism) somehow means that his seemingly new-fangled idealism (i.e., with frequent mentions of science) isn’t “mysticism”. Yet Kastrup himself often talks of religious, spiritual and mystical matters in very direct relation to his own Cosmic Idealism — see here, here and here. (Kastrup ties his personal idealism to purely political matters too — see here.)

And then we even have a long and wild jump from Heisenberg’s stress on measurements to Kastrup’s “transpersonal mind” (see the ‘transpersonal movement’). As Shawn Radcliffe writes (in a website called Science and Nonduality):

“For Kastrup and his colleagues, these types of measurements [in quantum mechanics] can only be performed by a conscious observer. They write that inanimate objects like a particle detector can’t truly measure a particle. With the double-slit experiment, ‘the output of the detectors only becomes known when it is consciously observed by a person,’ writes Kastrup. Extending this to all of reality, he argues that a ‘transpersonal mind’ underlies the material world.”

So is talk of “a transpersonal mind” really any better than talk of a merely “personal” idealism? If anything, Cosmic Idealism is more mystical than subjective idealism. Thus using phrases like “according to natural laws” and often mentioning physics, neuroscience (see here) and the other sciences doesn’t salvage Kastrup’s Cosmic Idealism from mysticism.

Indeed why does Kastrup deny his mysticism in one breath (as in the quote above) only to openly embrace it in the next breath? In this an example of Kastrup’s supposed philosophical depth and subtlety or simply a case of him having his cake and eating it too?

Take Kastrup’s many discussions of Carl Jung and the latter’s extremely strong influence on him. (Here’s Kastrup “discussing the mystical aspects of Carl Jung”.) Some people, perhaps Kastrup at other times, deny that Jung was a mystic. It can also be conceded that the the word “mysticism” can be used as a mindless term of abuse, much like Kastrup’s very-often-used term “materialist”. (It’s worth stating here that the term “New Agers” isn’t an ad hominem. Many New Agers class themselves as “New Agers” — see here.)

Heisenberg on 19th-Century Materialism

Much-quoted passages such as the following are used to advance the Heisenberg-was-an-idealist position:

“But the atoms or the elementary particles or possibilities rather than one of things or facts.”

Apart from that passage (at least in itself) being neither a direct nor an indirect argument for idealism, we can move on to other quotes too. Take the idealists (in this case Deepak Chopra again ) who’ve written such things as the following:

“As Heisenberg put it, electrons and other particles are not real but exist only as ideas or concepts. They become real when someone asks questions about Nature, and depending on which question you ask, Nature obligingly supplies an answer.”

Elsewhere, we also have this passage in the website Science & Nonduality:

“This phenomenon led physicist Werner Heisenberg to write in 1958, ‘The idea of an objective real world whose smallest parts exist objectively in the same sense as stones or trees exist, independently of whether or not we observe them [] is impossible.’ [].”

Again, the two passages above are not expressions of idealism from Heisenberg. It’s true that an idealist position can be extracted from them. However, (to be rhetorical) anything can be extracted from anything if one tries hard enough.

Yet Heisenberg did indeed castigate 19th-century materialism and the materialism which existed immediately before the “quantum revolution” of the 1920s.

For example, Heisenberg put his position very simply when he wrote this passage:

“The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory has led the physicists away from the simple materialistic views that prevailed in the natural science of the nineteenth century.”

And, elsewhere, Heisenberg wrote the following words (which are also often quoted — especially in the idealist memes found on Facebook and social media generally):

“The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct ‘actuality’ of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation, however, is impossible [] atoms are not things.”

In basic terms, then, with the rise of quantum physics in the 1920s, some physicists (not only Heisenberg) came to believe that the nature of matter (or the concept of matter) had been fundamentally altered. Of course other physicists didn’t believe this (more of which later.)

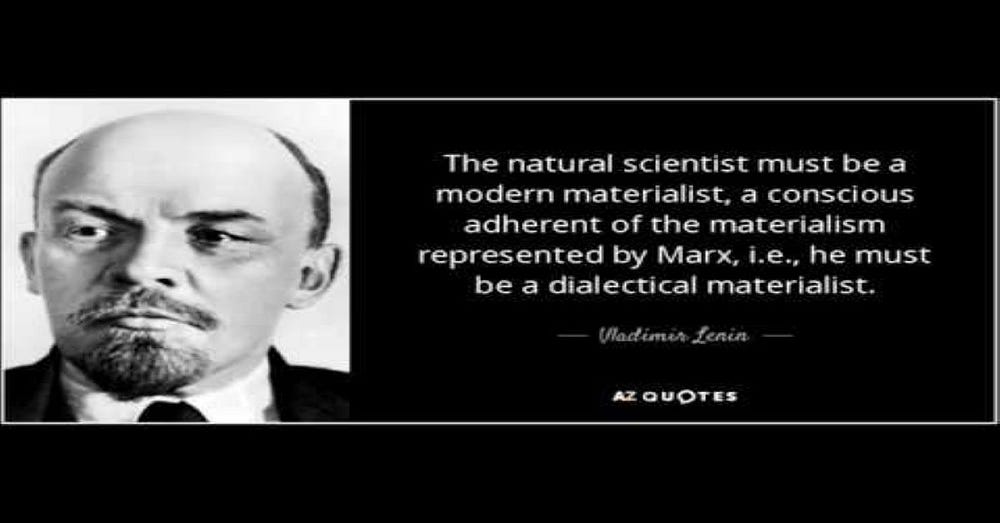

Heisenberg on Dialectical Materialism

Just as many contemporary idealists conflate materialism itself with 19th-century materialism, so Heisenberg himself had two brands of materialism in mind when he made his critical remarks: 19th-century materialism (as a whole); and, more specifically, dialectical materialism.

Heisenberg quoted one Soviet dialectical materialist and physicist Dmitry Blochinzev in the following passage:

“Among the different idealistic trends in contemporary physics the so-called Copenhagen school is the most reactionary. The present article is devoted to the unmasking of the idealistic and agnostic speculations of this school on the basic problems of quantum physics.”

So according to this dialectical materialist (Blochinzev), idealism is “reactionary”. The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics is idealist. Therefore the Copenhagen interpretation is also reactionary.

Blochinzev’s main problem was that the Copenhagen interpretation didn’t abide by the dictates of dialectical materialism. Thus Blochinzev quoted Lenin to back himself up; and that passage, in turn, was quoted by Heisenberg. Thus:

“[] ‘However marvellous, from the point of view of the common human intellect, the transformation of the unweighable ether into weighable material, however strange the electrons lack of any but electromagnetic mass, however unusual the restriction of the mechanical laws of motion to but one realm of natural phenomena and their subordination to the deeper laws of electromagnetic phenomena, and so on — all this is but another confirmation of dialectical materialism.’[].”

As one can see, this reads like a religious tract. Indeed Heisenberg himself picked up on this when he responded by saying that this defence of dialectical materialism (from Lenin)

“seems to degrade it [“quantum theory”] to a staged trial in which the verdict is known before the trial had begun”.

So one can see why Heisenberg (as it were) had in in for materialism if his main and most influential experiences of materialism was the dialectical materialism of the 1920s and beyond.

Elsewhere, and perhaps not specifically aiming his words at dialectical materialists, Heisenberg notes the problem with positions like Blochinzev’s and Lenin’s (which can also work as a warning to idealists) when he warned that

“the scientist should never rely on special doctrines, never confine his method of thinking to a special philosophy”.

The scientist should, instead,

“always be prepared to have the foundations of his knowledge changed by new experience”.

But it wasn’t only the dialectical materialists and 19th-century materialists Heisenberg had his eyes on.

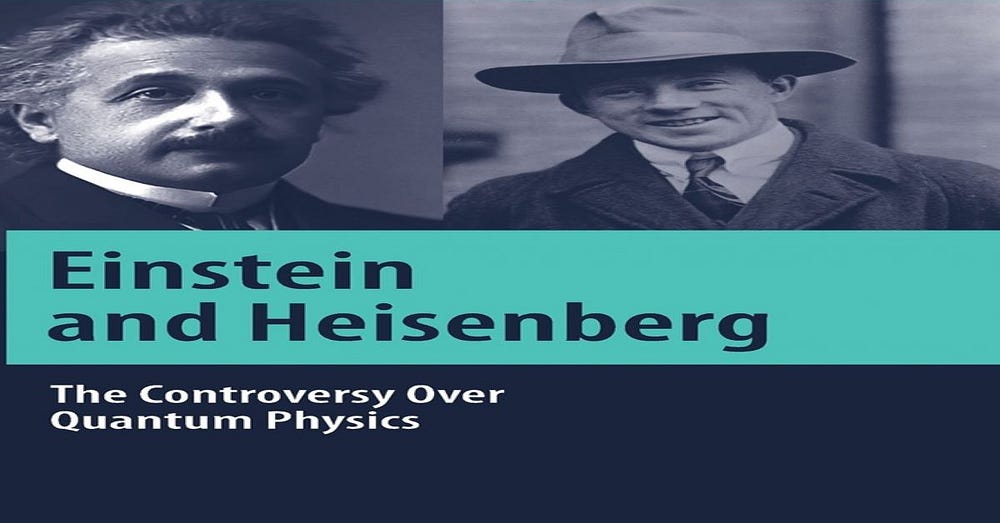

Heisenberg on Einstein’s Materialism and Realism

Heisenberg was certainly against realism — or at least he was against what he called “dogmatic realism”. So what is the link between realism and materialism?

Heisenberg detected what he called “materialism” among his fellow physicists. And it’s here that, to my 21st-century mind, Heisenberg appeared to conflate materialism with realism...

… That is unless either materialism must lead to realism or realism must lead to materialism. Alternatively, do contemporary idealists view materialism as being an actual subset of realism? (Idealists, like Bernardo Kastrup, certainly tie materialism and realism very closely together — see here.)

In specific reference to Albert Einstein, Max von Laue and Erwin Schrodinger, Heisenberg wrote:

“However, all the opponents of the Copenhagen interpretation do agree on one point. It would, in their view, be desirable to return to the reality concept of classical physics or, to use a more general philosophic term, to the ontology of materialism. They would prefer to come back to the idea of an objective real world whose smallest parts exist objectively in the same sense as stones or trees exist, independently of whether or not we observe them.”

So, on Heisenberg’s reading, materialism is a kind of realism. And realists believe in what’s often called an “objective world”. In Heisenberg’s own words:

“Quantum theory does not allow a completely objective description of nature.”

Thus, being a philosophical position, materialism needn’t always be naturalist in nature (see here). That is, it needn’t be cognisant of the sciences and their findings. Indeed, in this case, clearly such realists or materialists were rejecting the findings of physics — or at least they were rejecting the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory. In other words, the scientists who were also realists (just like contemporary “analytic metaphysicians”) believed that their personal philosophies could trump the findings of physics. (See, for example, the philosopher E.J. Lowe doing so in the chapter here.) In more clear terns, because the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory — and perhaps quantum mechanics itself — went against both “classical physics” and realism, Einstein, von Laue, Schrodinger and Bohm (among others) believed that it must be wrong in some way. That is, their prior philosophies (as I read Heisenberg’s position) were telling them that the Copenhagen interpretation was wrong!

This is how Heisenberg himself put it:

“Thus Einstein hoped that beneath the chaos of the quantum might lie hidden a scaled-down version of the well-behaved, familiar world of deterministic dynamics.”

Yes, the above is an indirect reference to those famous hidden variables. Or in Heisenberg’s own words again, a reference to

“a deeper level of hidden dynamical variables that effect the system and bestow upon it merely an apparent indeterminism and unpredictability”.

Heisenberg’s problem with materialism also (at least partly) stemmed from accounts of what was deemed “objective” in physics. And, of course, any talk of what is objective has been tied to the philosophical positions of realism, not only to materialism.

In any case, Heisenberg himself once wrote:

“The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct ‘actuality’ of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation is impossible, however.”

Of course this passage won’t work very well for contemporary idealists because Heisenberg clearly restricted his claim to “the atomic range”. Idealists, on the other hand, apply their position to the entire universe and literally everything in it. In other words, contemporary idealists have “extrapolated” what Heisenberg and other physicists said about the atomic range into the “the world around us”. And that is precisely what Heisenberg warned against.

(Heisenberg wasn’t actually warning idealists about this: he was warning those who demanded a “classical picture” of quantum theory.)

But do any of Heisenberg's criticisms of the realism of Einstein and others necessarily lead to (philosophical) idealism?

Heisenberg on Positivism and Idealism

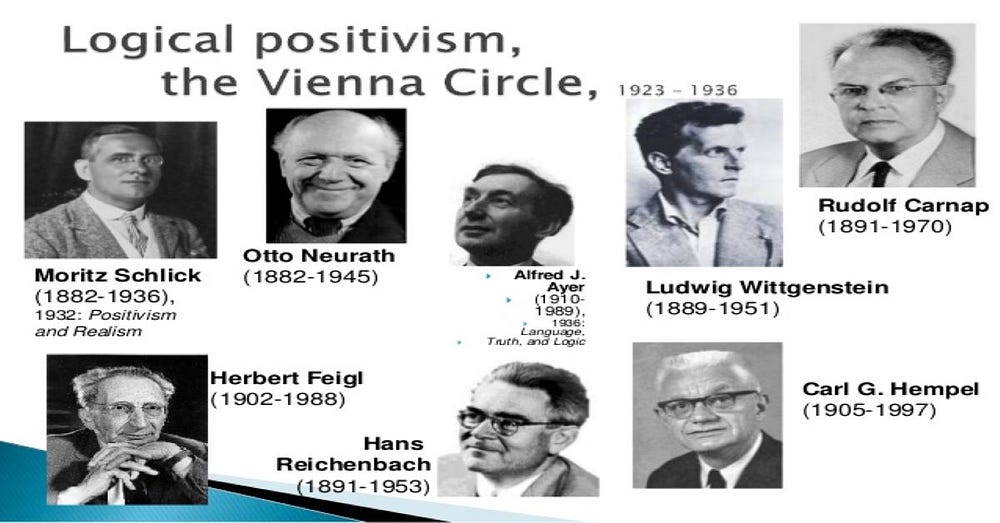

Many idealists and anti-materialists also tend to conflate (or fuse) materialism with logical positivism — and logical positivism is the victim of a very special disdain.

Of course the logically positivism of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s grew out of positivism, which dated back to the 19th century. That said, it does seem to be the case that Heisenberg mainly had logical positivism in mind in the passages quoted in the following. That’s not surprising, Heisenberg’s words date from 1955/6 — not long after the “demise of logical positivism”.

Ironically enough, Heisenberg himself has often been classed as a “positivist” (see here). Indeed he was very positive toward positivism in the 1920s and 1930s. However, he later changed his mind on the merits of positivism. (See here.) For example, much later (in 1955/6) he stated the following:

“It should be noticed at this point that the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory is in no way positivistic. For, whereas positivism is based on the sensual perceptions of the observer as the elements of reality, the Copenhagen interpretation regards things and processes which are describable in terms of classical concepts, i.e., the actual, as the foundation of any physical interpretation.”

In other words, if anything, it was positivism (i.e., not the Copenhagen interpretation) that was subjectivist, if not idealist! And that was certainly true if one bears in mind, for example, the (to use Heisenberg’s words) “sensual perceptions” which were stressed by logical positivist philosophers such as Rudolph Carnap (1891–1970)…

In actual fact, however, Carnap used phrases like “cross-sections of experience”. Still, Carnap’s cross-sections of experience were hardly “describable in terms of classical concepts”. Like “sense data”, they were actually highly-artificial terms of art (i.e., the inventions of philosophers), not what Heinsberg called classical concepts.

Heinsberg's position is made even clearer when he discussed (straight after tackling Bishop Berkeley’s idealism) what he called “empiricist philosophy” . Indeed, in the following passage, Heisenberg might very well have been discussing various logical positivists and sense-data theorists too. He wrote:

“Our perceptions are not primarily bundles of colors and sounds; what we perceive is already perceived as something, the accent here being on the word ‘thing,’ and therefore it is doubtful whether we gain anything by taking the perceptions instead of the things as the ultimate elements of reality.”

Heisenberg was even clearer about (as it were) positivist subjectivism (not positivist idealism) when he wrote the following:

“Certainly quantum theory does not contain genuine subjective features, it does not introduce the mind of the physicist as a part of the atomic event.”

Heisenberg continued by arguing that quantum theory

“starts from the division of the world into the ‘object’ and the rest of the world, and from the fact that at least for the rest of the world we use classical concepts in our description”.

What is Materialism?

As with so much in philosophy, then, Heisenberg’s position entirely depends on how he defined the term “materialism”. It also depends on what particular materialists actually believed at the times he spoke about materialism.

It also has to be kept in mind that it’s an obvious fact that before quantum mechanics, materialists — both philosophers and scientists — wouldn’t have had a (as it were) quantum take on matter… But that’s simply because no one did! Indeed even quantum physicists didn’t agree — or fully comprehend — the philosophical (or ontological) implications of quantum mechanics in the 1920s and well beyond.

So why do contemporary idealists single out the materialists of the 1920s and before and what Heisenberg had to say on them?

The point being made here is that there was never any necessary reason for materialists to believe that atoms are (to use Heisenberg’s word) “things”. That’s because materialists believed that atoms are things when most physicists believed — and some still do — that atoms are things. That said, when certain (quantum) physicists started to question that simple “classical picture”, then so too did many materialists. In other words, such materialists were taking their cue from physics.

So now let’s bring this issue right up to date.

Today there’s no reason why a materialist should ever have a problem with, say, the Lambda-CDM model. In this model, old-style “matter” only makes up 5% of the density level of the universe. That is, certain — perhaps many — physicists now believe that 95% of the universe is made up of dark matter and dark energy.

Again: the important point here is that (regardless of the accuracy of the technical details) many materialists go with the science — even if materialism is not itself a science.

Materialism Through the Eyes of Idealists

As already stated, many idealists and anti-materialists seem to conflate materialism with what many materialists believed in the 19th century — or at least up until (roughly) the 1920s. In other words, contemporary idealists have a view of materialism that might have been correct in the 19th century and the early 20th century. Yet even by the 1930s — if not before — this stereotype of materialism was no longer the case when it came to many (philosophical) materialists.

All this largely boils down to idealists and anti-materialists claiming that materialists believe that all matter — and indeed everything else — is what they call “tangible stuff”. Indeed the frequent claim used to be — and sometimes still is — that materialists believe that everything is made up of “hard particles”.

More relevantly, contemporary idealists can — and often do — bring up Heisenberg in this respect.

So at the heart of Heisenberg’s technical problem with materialism was his stress on the matter-energy (or matter-force) distinction.

For example, Heisenberg made things clear in the following passage:

“A clear distinction between matter and force can no longer be made in this part of physics, since each elementary particle not only is producing some forces and is acted upon by forces [].”

Despite those words, everything had already begun to change with field physics in the 19th century — which all (naturalist) materialists almost immediately took on board. Why was that? It was largely because such materialists (i.e., not all materialists) weren’t mindlessly committed to tangible stuff or to anything else like that — they were committed to the findings of physics and the other sciences. And physicists discovered fields (other than gravity) in the 19th century (see here).

In addition, when Einstein showed that matter and energy are interchangeable, many materialists immediately took that on board too. Thus, as an obvious consequence of that, many materialists also came to believe that energy — not matter — is (as it were) prima materia… Or at least they came to believe that matter is a form of energy.

And something similar occurred with the rise of quantum field theory.

Again, many materialists took quantum field theory on board. That is (as with Einstein’s equation of matter and energy), materialists came to see that fields — not energy — are prima materia; and therefore that energy and particles are properties of such fields.

The important point here, then, is (even if the technical details of physics are misinterpreted) that although there was a (radical) shift in a part of physics, many materialists still took on board these new findings, commitments and theories of physics.

So let the Australian philosopher Keith Campbell (1938-) sum up all the above in the following words:

“What the claim to materiality amounts to changes as physics changes. In the eighteenth century, (1) would assert that all events involving the body can be explained by reference solely to impact and gravitation among particles. And this is false, for the body is electromagnetic as well as mechanical. In the twentieth century, (1) embraces electromagnetism, for that is part of contemporary physics. The content of the claim that an object is material is relative to the physics of the time it is made.”

Conclusion

Finally, Heisenberg expressed a position which seems to chime in perfectly with what is called anti-realism — i.e., not idealism. (On some readings of metaphysical anti-realism, admittedly, it’s almost indistinguishable from idealism — see here.) That is, Heisenberg’s position strikes a middle way between realism and idealism.

Heisenberg began one passage with the following words:

“It has been pointed out before that in the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory we can indeed proceed without mentioning ourselves as individuals [].”

It can of course be said that claiming that the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory “can indeed proceed without mentioning ourselves as individuals” may not amount to much. After all, that may only be a formal requirement of the interpretation that it simply doesn’t mention (or it overlooks) the perspectives or experiences of individuals. Yet that, in itself, doesn’t mean that it isn’t based on individual experiences, minds, observers, etc.

But then Heisenberg continued:

“[W]e cannot disregard the fact that natural science is formed by men. Natural science does not simply describe and explain nature; it is part of the interplay between nature and ourselves; it describes nature as exposed to our method of questioning.”

Here the very acceptance of what Heisenberg called “nature” hints at a non-idealist picture. More specifically, the phrase “the interplay between nature and ourselves” is an acknowledgement that, on the one hand, there is nature, and, on the other hand, we have ourselves. Yet surely in the idealist story there is only ourselves (i.e., according to Objective idealism or Cosmic Idealism) or even only oneself (i.e., according to Subjective Idealism).

Of course an idealist like Bernardo Kastrup would get around this by arguing that this nature (he prefers the word “reality”) is itself is part of Cosmic Consciousness (or that nature is a “projection” of a “collective consciousness”). So this is just a case of “disassociated” individuals (in this instance it just happens to be physicists) reconnecting with Cosmic Consciousness as it is instantiated in what is called nature.

Yet it is almost certainly the case that Heisenberg himself would have laughed at this position. That is, there is no evidence whatsoever that he would have endorsed this idealist reading of his own position.

*********************************

Notes:

(1) Heisenberg’s position above on “things” or individuals, as first stated in 1955/56 at the Gifford lectures, was philosophically replicated by the philosopher P.F. Strawson in his 1959 book, Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics.

(2) Why do idealists never quote the anti-subjectivist and anti-idealist words of Heisenberg in their articles and social-media memes? At least the passages from Heisenberg which idealists quote have also been referred to above.

*) Part Two is to follow. This will be a more (philosophically) technical account of Werner Heisenberg’s philosophy of physics as it relates to contemporary idealism.