The British philosophers P.M.S. Hacker (Peter Hacker) and Paul Horwich speak out against scientism in contemporary analytic philosophy.

[See my previous essay, ‘Two Worshippers of Wittgenstein: Paul Horwich and Peter Hacker’.]

“[Scientism is] an exaggerated trust in the efficacy of the methods of natural science applied to all areas of investigation (as in philosophy, the social sciences, and the humanities). [] [S]ome scholars, as well as political and religious leaders, have also adopted it as a pejorative term [].”

— See source here.

Dating back to the late 19th century, many philosophers, religious commentators and others have stated that bad philosophy “mimics science”. More relevantly to the theme of this essay, this has also been said specifically about analytic philosophy. [See here and here.]

One account of philosophical scientism I came across (which mentions Paul Horwich, who’ll be discussed in a moment) just seems like fantasy to me. Here is that account:

“It is this scientistic nature that in Horwich’s reading of Wittgenstein is based on the illusion that the philosopher, just like the scientist in the empirical sciences, can make fundamental discoveries if only he uses the same kind of methods the scientist applies to analyze his a posteriori data.”

The fantasy here isn’t that of philosophers attempting to mimic science. The fantasy is believing that all?/most?/many? philosophers have ever done such a thing. More particularly, the fantasy is believing that analytic philosophers particularly have attempted to make “fundamental discoveries” by “us[ing] the same kind of methods the scientist applies to analyze his a posteriori data”.

It was Ludwig Wittgenstein particularly who started this (as it were) anti-scientism war — at least against the philosophers he had in mind at the time. [Mainly the logical positivists. See here too.]

The British philosopher Paul Horwich continues this (Wittgensteinian) anti-scientism-in-philosophy war.

Sure, the charge of “scientism” (with its “hissing suffix”) might well have been true of some philosophers who were around when Wittgenstein was writing (say, from the 1920s to the early 1950s). However, has it really been true of all analytic philosophers since the 1920s until today?…

Has it been true simply of most of them?

Many of them?

Or just some of them?

It can be argued that there was never any literal mimicking of science by any philosophers anyway — even back in Wittgenstein’s day. Sure, materialists, naturalists and positivists admired science. Indeed, they looked to science for philosophical inspiration. However, none of that is the same thing as actually “imitating science”.

So perhaps Paul Horwich’s distinction here is actually between those philosophers who self-consciously mimic science, and those who somehow mimic science by default (or by habit).

Thus, perhaps Horwich has the latter philosophers in mind.

However, even this qualification can be questioned.

Hacker and Williamson on Science and Philosophy

On the one hand, “philosophy” (actually, Horwich and Hacker mean analytic philosophy) gets it in the ear for its (as it’s put) apriorism. On the other hand, it’s also accused of scientism. That said, Paul Horwich’s additional argument is that philosophy could never actually be scientific. Thus, all it can do is mimic science in a rather pedestrian and/or naive way.

So let’s move on to British philosophers P.M.S. Hacker (Peter Hacker) and Timothy Williamson here.

One can see how a Wittgensteinian would have serious problems with what Timothy Williamson says about the relation of philosophy to science.

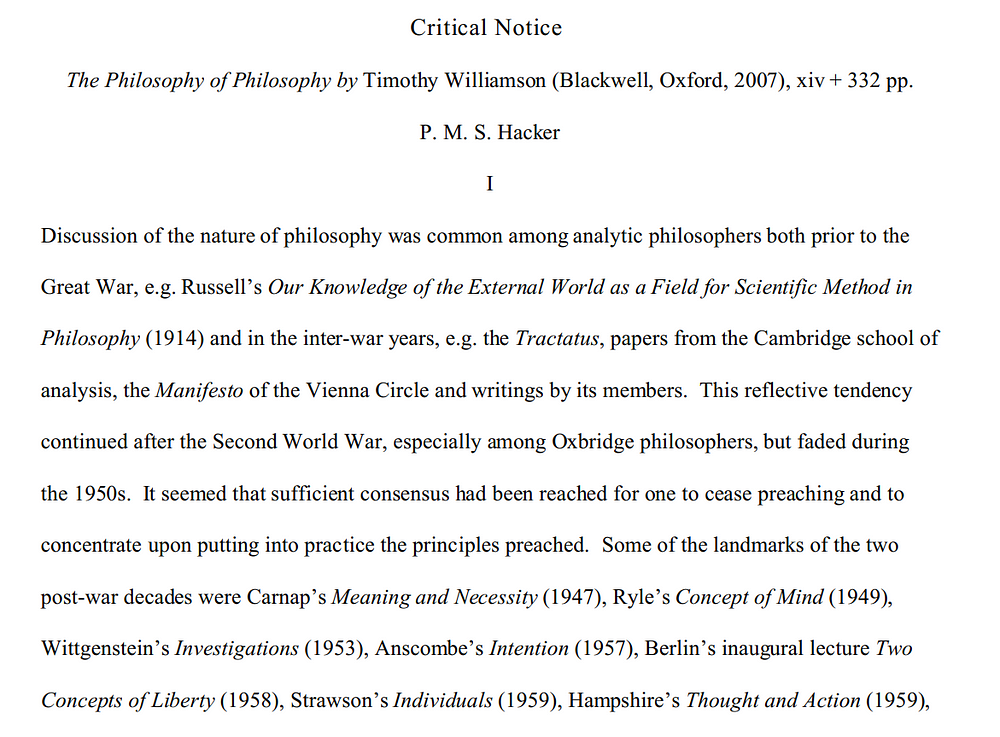

Peter Hacker writes:

“Three themes dominate the book [i.e., Timothy Williamson’s Philosophy of Philosophy]. First, that it is false that the a priori methodology of philosophy is profoundly unlike the a posteriori methods of natural science; indeed that very distinction allegedly obscures underlying similarities. Second, that the difference in subject matter between philosophy and science is less deep than supposed; ‘In particular, few philosophical questions are conceptual questions in any distinctive sense’. Third, that much contemporary philosophy is vitiated by supposing that evidence in philosophy consists of intuitions, which successful theory must explain.”

As already hinted at, Wittgensteinians don’t like “philosophical apriorism”. And they don’t like philosophical scientism either. Hacker believes that Williamson is guilty of both these sins against Wittgensteinian philosophy.

In any case, perhaps all that the words “a priori methodology of philosophy” basically mean is that such philosophy isn’t… well, science. In other words, philosophers don’t employ (to use Peter Hacker’s words) “measurement, observation or experiment”. [Note: observation is the odd one out here.]

In detail.

In the passage above, Hacker quotes Williamson stating that

“few philosophical questions are conceptual questions in any distinctive sense’”.

Perhaps it would have been better if Williamson stated the following instead:

Few philosophical questions are purely conceptual in any distinctive sense’.

Arguably, Hacker, on the other hand, believes that (virtually?) all philosophy should be conceptual analysis. (He comes very close to actually stating this. See here.) Yet Williamson too is wrong to play down “conceptual questions” entirely. Thus, both Hacker and Williamson — at least as quoted here — seem to offer their readers equally extreme positions.

As for “intuitions”.

Hacker has it that Williamson believes that

“evidence in philosophy consists of intuitions, which successful theory must explain”.

Many naturalists and physicalists are suspicious of intuitions too. Yet they usually aren’t also Wittgensteinians. In addition, explaining intuitions isn’t the same as placing them on a untouchable pedestal.

In any case, Peter Hacker also claims that Timothy Williamson sees “fundamental similarities between philosophical and scientific knowledge”. More specifically, Williamson is said to make a move from the “armchair” to “knowledge of truths about the external environment”.

Yet Hacker also hints at (as it were) philosophical apriorism in the following passage:

“It consists of thinking, without any special interaction with the world beyond the armchair, such as measurement, observation or experiment would typically involve.”

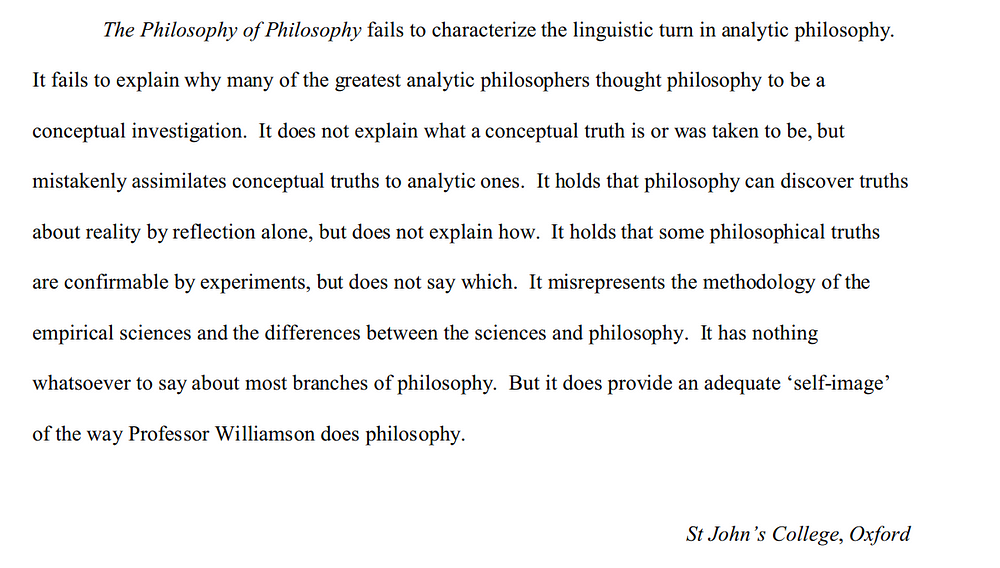

Whatever the answers to these questions are, Hacker also says that Williamson “holds that philosophy can discover truths about reality by reflection alone”. Despite that, Williamson also believes that “some philosophical truths are confirmable by experiments”.

That last passage may simply mean that even though “philosophical truths” are “armchair” phenomena, then there’s still nothing to stop them from being backed-up (or “confirmable”) by scientific experiments — or by other a posteriori factors. (This is a little like Laurence BonJour’s position on a priori statements.)…

Actually, if a philosophical truth is indeed a philosophical truth, then some philosophers would argue that it can hardly be contradicted by scientific experiments. And — almost as a consequence of this — it must be confirmable by them too. However, all that would depend on whether experiments can have any impact on such philosophical truths at all.

Thus, in the case of certain philosophical truths at least, it can also be said that scientific experiments can neither confirm nor disconfirm them. In other words, experiments are basically irrelevant to most (or perhaps simply many) philosophical truths.

Hacker offers us more on Williamson’s position:

“[S]ince philosophical ways of thinking are no different in kind from other ways, philosophical questions are not different in kind from other questions. Most importantly, philosophy is no more a linguistic or conceptual inquiry than physics.”

As for Williamson himself, he’s attempting to bridge the gap between philosophy and science when he says that “[p]hilosophy, like any other science (including mathematics) [ ] has evidence for its discoveries”. Williamson then says (i.e., against people like Peter Hacker) that “philosophy is no more a linguistic or conceptual inquiry than physics”.

Does all the above basically mean that philosophy both is and is not like science?

No comments:

Post a Comment