This essay is mainly about Keith Donnellan’s paper ‘Speaking of Nothing’, and its defence of a causal theory of reference.

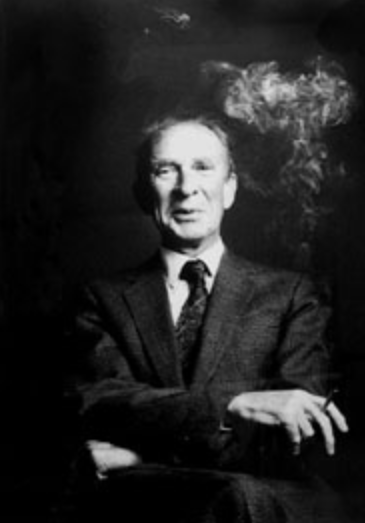

The American philosopher Keith Donnellan (who died in 2015) believed that the statement

“Santa Claus will come tonight.”

isn’t actually a genuine proposition.

In his paper ‘Speaking of Nothing’ (1974), Donnellan asked the following question:

“[C]an one even speak and be understood when using a singular expression with no referent?”

However, Donnellan did accept this paraphrase:

“According to the legend, Santa Claus will come tonight.”

Donnellan deemed that statement to be true.

So, according to the legend, Santa will come on that night. However, the legend doesn’t also say, “Santa Claus doesn’t actually exist [or he does exist]”.

At an intuitive level, it’s hard to see what Donnellan’s problem was.

The legend itself doesn’t really have any position on Santa’s actual existence…

But so what?

Why does that make a kid’s statement (i.e., “Santa Claus will come tonight.”) not understandable? Indeed, why does it make it non-propositional? Why impose ontological rectitude onto meaning, and the very acceptance of a proposition qua proposition?

What is the connection here?

Isn’t it only the belief that a non-existent is an existent that’s at fault here? However, does that render this statement itself non-propositional?

So readers should focus again on Donnellan’s idea that the sentence “Santa will not come tonight” isn’t a proposition.

Why?

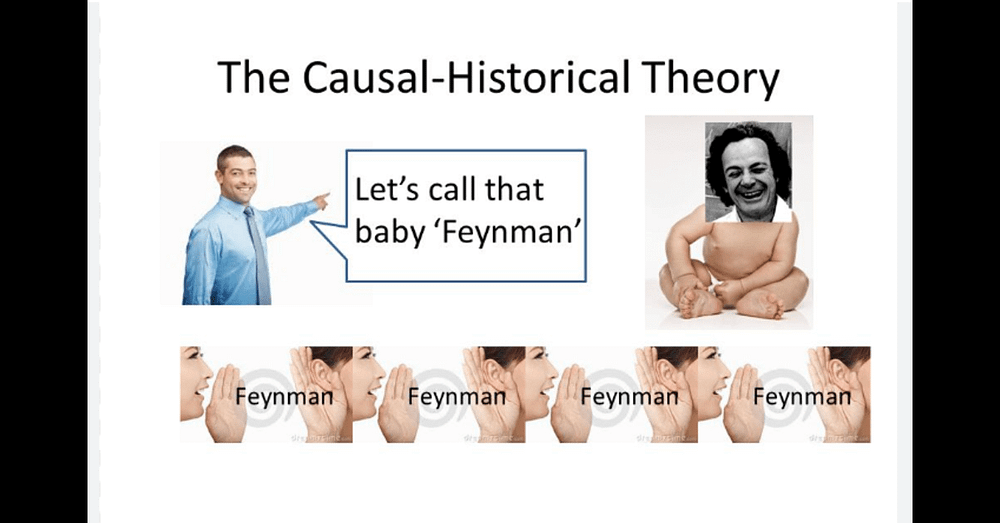

According to Donnellan, a proper name (in this case, “Santa Clause” or “Santa”) must have one of two things:

(1) It must be causally connected to its referent.

(2) It must have “descriptive content”.

It seems that Donnellan believed that the name “Santa” has neither. That is, if that scare-quoted “name” has no “historical connection” to its referent (which it can’t have because Santa never existed), then the proposition “Santa will come tonight” can’t be a proposition. And it can’t be a proposition because of the problematic proper name.

Yet isn’t it simply a stipulation (or even a diktat) to argue that “Santa will come tonight” isn’t a proposition?…

In logic, however, all propositions must be either true or false.

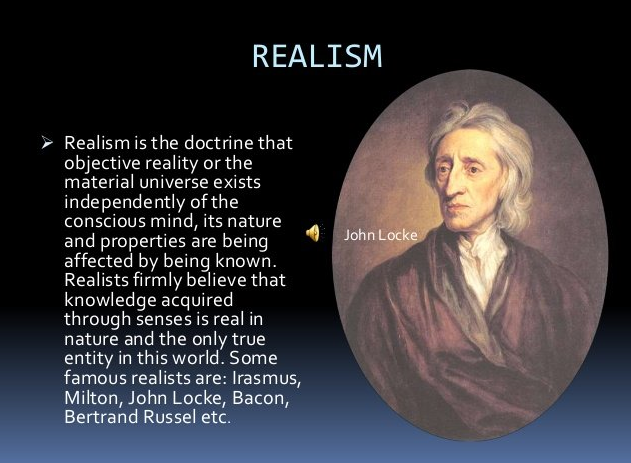

Philosophical Realism?

The thing which seemed to be motivating Keith Donnellan was his attempt to save philosophical realism. In other words, if we can have a causal theory of reference which evidently excludes names like “Santa”, then we can distinguish real propositions like “Brad Pitt will come tonight” from “Zeus is angry with us”.

[The statement about Brad Pitt is a future contingent, which is also problematic — if for different reasons.]

There’s another realist move in this game.

Donnellan — and many other philosophers (such as Saul Kripke) — argued that proper names shouldn’t rely on being tied to “descriptive content”. They believed that this would give individual minds (as it were) too much power, and direct causal reference less power.

Associating descriptive content with proper names has also been deemed to be idealist by some philosophers. (“Subjective” is a better term than “idealist” in this context.) A causal connection to Brad Pitt (or the “Brad Pitt” relation to Brad Pitt) is concrete. “The rubbish [or great] actor in Hollywood” is subjective, or at least dependent on an individual mind (or on individual minds in the plural). Similarly, the definite description that I’ve personally tied to the name “Santa” may be very different to the one you’ve personally tied to that name.

So what would secure us an identity of reference here when it comes to the names “Santa” and “Brad Pitt”?

Donnellan’s causal theory of reference (which excludes Santa) is the realist’s way of avoiding not just idealism (or, better, subjectivity), but also relativism.

Conventions, conceptual schemes, identifying descriptions, etc. were also deemed to be “subjective” by Donnellan. Causal processes, on the other hand, impose themselves on us. In other words, they tie us firmly to the world.

Bertrand Russell, God and Sherlock Holmes

To finish, let’s now agree with Keith Donnellan’s rejection of Bertrand Russell’s view on this matter.

Donnellan argued that the statement

“God does not exist.”

isn’t an abbreviation for Russell’s

“There is no entity such that…”

So why does “failure of a complex reference simply make a proposition false”?

What is a failure of reference?

For example, can’t we refer to something non-spatiotemporal?

Indeed is, say, Santa or Sherlock Holmes really a non-spatiotemporal entity at all?

Perhaps we can say that Santa or Holmes exists in minds, on the page, in letters, on the screen, in pictures, etc. All these are spatiotemporal things.

However, aren’t these examples simply representations of Santa and Holmes?

That would be the case if he were something other than Santa’s or Holmes’s representations.

In any case, in the works of Conan Doyle, Holmes is meant to be… Holmes: he isn’t a representation of Holmes.

So reference needn’t be to something that’s spatiotemporal in the strict sense of Holmes being made of flesh and blood…

We refer to numbers after all.

We refer to the number 2. The number 2 isn’t concrete. It isn’t (on most readings) spatiotemporal .

So is a negative statement like “John is not here” a reference to something spatiotemporal?

Well, in one sense, yes.

Part of the referent is the space not filled by John. In addition, even though John is not there, John himself is still a spatiotemporal entity.

What about the non-spatiotemporal nature of historical facts?

Can we simply say here that at on point historical events were spatiotemporal? So historical facts are parasitical on these past spatiotemporal events.

Peter Strawson on Statements About God

Now take Peter Strawson’s position.

According to Strawson, the statement

“God is in heaven.”

is neither true nor false, because Strawson deemed the statement

“There exists something which is God.”

to be false.

Thus, the statement “God is in heaven” must be neither true nor false because there’s no God to be in heaven… or to be anywhere else. Of course, the statement “There exists something which is God” is making a claim about existence, not about the whereabouts of an existent.

Thus, according to Strawson’s atheistic ontology, the sentence “God is in heaven” is plainly suspect. How can it be true that “God is in heaven” when (it is supposed that) there is no God? Yet how can it be false that “God is in Heaven” for exactly the same reason?

On this picture, then, the subject, God, doesn’t exist. Thus, the predicate phrase, “is in Heaven”, can be neither true nor false of the subject term.

Yet perhaps we can still say that the statement “God is in heaven” is false without indulging in (or adding) existence-claims. If it’s false that there is God (and heaven), then it’s also false that God is in heaven. Thus, the whole statement is false. Or, rather, you can say it’s false (or true) because of one’s prior position on God’s existence. However, you shouldn’t thereby deny its status as a proposition.

If we do deny the propositional status of “God is in heaven”, then perhaps we can also call that sentence meaningless! Indeed, roughly speaking, this was the position of some logical positivists in the 1930s and 1940s. [See my ‘The Logical Positivists’ Use of the Word “Meaningless”: A Retrospective’.]

Yet we can’t allow this for the simple reason that the statement “God is in heaven” isn’t meaningless! It may well be philosophically problematic. However, the statement clearly isn’t without meaning.

No comments:

Post a Comment