This essay doesn’t (as it were) have a go at religion. Instead, it simply highlights how poor Stephen Jay Gould’s arguments are. Indeed, it also argues that Gould’s arguments are poor precisely because his prime motivation was one of political diplomacy between science and religion. It should also be noted here that this essay doesn’t even consider Gould’s crude and simplistic advocacy of the fact/value distinction, as it applies to science and religion.

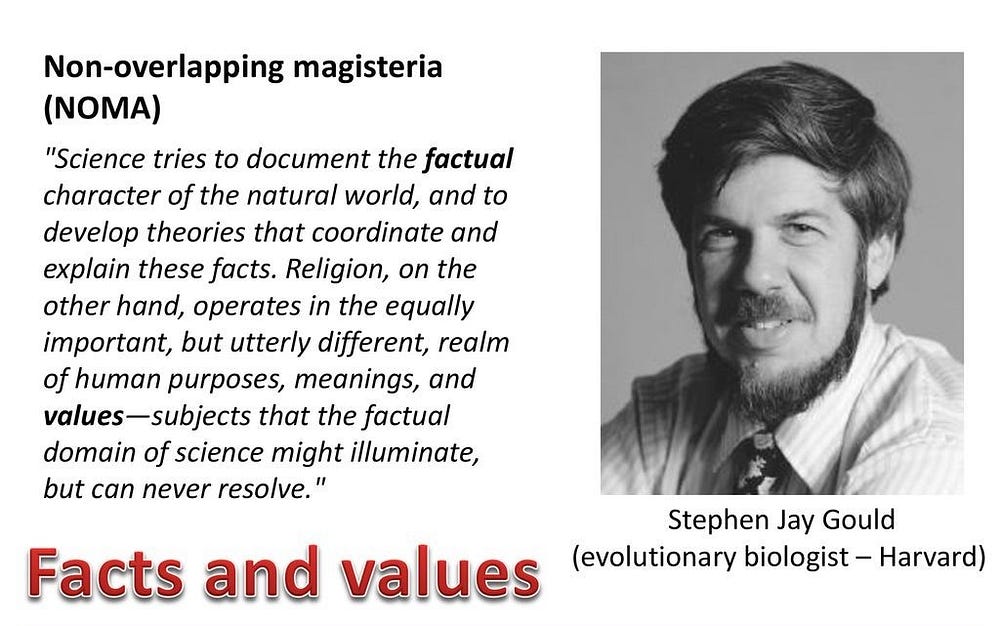

Stephen Jay Gould (1941 — 2002) was an American palaeontologist, evolutionary biologist and a historian of science.

Gould was also known for his popular essays (one of which is central to this piece) in the magazine Natural History, and also for his best-selling books.

Introduction: Non-Overlapping Magisteria?

Stephen Jay Gould first expressed the position focussed upon in this essay in 1997. It can be found in an essay called ‘Non-overlapping Magisteria’, which Gould wrote for Natural History magazine. (He used it again in his 1999 book, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life.)

Gould’s most absolute and categorical expression of his science-religion division (abbreviated to NOMA) can be found in his simple statement that “[t]hese two magisteria do not overlap”.

Interestingly enough, the National Academy of Sciences also adopted a stance (in 1999) which was very much like Gould’s own. Its publication Science and Creationism stated the following:

“Scientists, like many others, are touched with awe at the order and complexity of nature. Indeed, many scientists are deeply religious. But science and religion occupy two separate realms of human experience. Demanding that they be combined detracts from the glory of each.”

[The National Academy of Sciences sees “political commitment” and “political engagement” as part of its remit — see here. Perhaps this was at least partly down to scientist-activists like Richard C. Lewontin — a friend of Gould and fellow member of the political group Science for the People — claiming that the NAS should take political positions on certain scientific subjects and issues. (See Lewontin’s ‘Why I Resigned from the National Academy of Sciences’, written in 1971.))

Readers may be surprised to know that Gould borrowed the term “magisterium” from Pope Pius XII’s encyclical Humani generis (1950). That’s said because Gould was a socialist. Indeed, according to many and even himself at times, he was a Marxist (see here). So note here that Gould most certainly wasn’t a Christian socialist. And he wasn’t a practising Jew either. He was an atheist (see here). That said, there’s much dispute on whether Gould was an out-and-out Marxist and an out-and-out atheist. Perhaps, then, Gould’s artful ambivalence on these classifications was politically and strategically —i.e., not philosophically — motivated. That is, it wasn’t really a result of Gould’s deep sophistication on matters of religion and science.

Gould’s politics has just been mentioned.

Gould’s Political Stance on Science and Religion

It can easily be argued that Stephen Jay Gould came up with his “non-overlapping magisteria” idea primarily for political reasons. That is, he believed that it’s far too politically dangerous to have a (as some commentators have put it) “crude and simplistic” attitude toward religion. In fact, in various and many places, Gould virtually admitted his political motivations on this subject (as we shall see throughout this essay).

Gould’s basic idea (which he sometimes stated outright) is that the various and many religions have so many adherents, have such a long history, and that religious people feel so very strongly about their chosen religion, that it would be politically crazy and (as it were) sadistic to take a strong line on them. (Professor of Psychology Ciarán Benson speaks in rhetorical terms about science being “sadistic” toward religion when it attempts to enforce “a brand of SM bondage of the others by the scientific magisterium”.) Indeed, it can even be argued that Gould believed that it would be crazy and sadistic to tell the truth about any of the many chasms and conflicts which obviously exist between religion and science.

So Gould’s position was essentially political.

Indeed, the fact that there are such chasms and conflicts between religion and science was precisely why Gould concocted his non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA) idea in the first place.

In Gould’s own words:

“Religion is too important to too many people for any dismissal or denigration of the comfort still sought by many folks from theology.”

The problem here is both simple and obvious.

Gould’s notion of non-overlapping magisteria seems to leave all religions (as well as all their claims) untouched by anyone on the outside. Or, at the very least, it leaves religions and their claims untouched by science.

It should also be said that religion would become untouchable if scientists, politicians, philosophers and everyone else followed Gould’s NOMA idea.

And, of course, if religion is untouchable by science, then it’s probably also untouchable by anything else… at least if the (as it were) touching is in any way negative or critical.

Stated in that way, then, Gould’s idea is quite incredible and indeed very dangerous. (Ironically, a cursory view of Gould’s political pronouncements — i.e., outside his NOMA idea — will show that he didn’t practice much political or, indeed, scientific diplomacy.)

It can now be said that Gould’s religion-science division is far too neat and tidy. It’s also far too convenient.

Gould’s Diplomacy When it Comes to Religion

It was just mentioned that Gould’s NOMA idea is far too neat, tidy and convenient. Indeed, Gould recognised this in the following passage:

“Each [] subject has a legitimate magisterium, or domain of teaching authority. [] This resolution might remain all neat and clean if the nonoverlapping magisteria (NOMA) of science and religion were separated by an extensive no man’s land. But, in fact, the two magisteria bump right up against each other, interdigitating in wondrously complex ways along their joint border.”

In basic terms, then, the logic of this argument is poor. After all, at one point in history (say, the late 1930s), there were tens of millions of Nazis in Europe and beyond. And, at another point in history (say, the 1940s), there were also tens of millions (perhaps over a hundred million) communists. (Many of them were full-blown supporters of Joseph Stalin.) So should we have refrained from (to change the tense of Gould’s own word) dismissing their views too?

What about today?

In 2023, there are tens of millions Islamists or “radicals”. (Some argue that there are between 180 million to 300 million Islamists or radicals.) And there are also millions of “Christian fundamentalists”. (I suspect that many people will question the terms “Islamists”, “radical” and “fundamentalist”.) So should we refrain from dismissing their views?

However, if Gould didn’t include Islamists, Christian fundamentalists, etc. in his religious magisterium, then how did he rationalise that selectivity? Would he have resorted to politics again? (Gould would have no doubt believed that my comparisons — or analogies — are unfair.)

So are (specific?) religions special?

Gould certainly believed that religion is special. And, as such, he also believed that religion should be treated as something special.

More on Gould’s Political and Diplomatic Stance

Gould’s desire for diplomacy (or at least diplomacy toward religion) was displayed when he told us that

“NOMA enjoys strong and fully explicit support, even from the primary cultural stereotypes of hard-line traditionalism”.

Gould continued by saying that NOMA is a

“sound position of general consensus, established by long struggle among people of goodwill in both magisteria”.

Gould’s political diplomacy was also based on body counts. He once stated that, according to polling data at the time, 80 to 90% of Americans believed in God. Thus, Gould concluded by stating that

“we have to keep stressing that religion is a different matter, and science is not in any sense opposed to it [if scientists don't accept that, then] we’re not going to get very far”.

… Except that Gould did not believe in diplomacy in all areas. As a political “radical”, he certainly didn’t believe in diplomacy toward the many people he deemed to be Nazis and fascists. And, arguably, Gould wasn’t known for his diplomacy toward those scientists who offered theories he believed to be (as many people on the Left often put it) “politically dangerous”. (As Gould expressed when a member of the political group Science for the People. See here.) And he wasn’t particularly diplomatic toward capitalists, Republicans, etc. either.

So, again, it’s clear that Gould gave religion a special status.

Gould’s political diplomacy was made even more clear when he described NOMA as a

“blessedly simple and entirely conventional resolution to [] the supposed conflict between science and religion”.

The words “supposed conflict between science and religion” are utterly bizarre. More particularly, the word ”supposed” is the prime offender.

Of course, there has been much conflict between science and religion. So surely Gould couldn’t have meant that there had been no conflict. Does that mean, then, that Gould believed that, in actual fact, there should be no conflict?

This depends on how strongly one takes the word “conflict” and on particular examples. In any case, perhaps there would be no conflict at all if everyone on both sides accepted and embraced Gould’s own idea of non-overlapping magisteria…

But they don’t!

And why should they?

Indeed, is this truce or pact even likely on a large scale?

Gould’s Other Motivations

Gould wrote:

“NOMA also cuts both ways. If religion can no longer dictate the nature of factual conclusions residing properly within the magisterium of science, then scientists cannot claim higher insight into moral truth from any superior knowledge of the world’s empirical constitution.”

So did Gould allow religion (as it were) free reign because he wanted to secure a reciprocal freedom for science?

Again, this just seems like a purely political and diplomatic advocacy of a truce.

Not that there’s anything wrong with diplomacy or with truces.

The point here, then, is that this is what Gould was doing and that should be made clear. Indeed, it all seems somewhat obvious.

Again, NOMA is so neat and tidy precisely because it was Gould’s political attempt at a diplomatic truce between religion and science. In philosophical and even scientific terms, however, Gould’s arguments are very poor. And that, again, is primarily because his main (or even only) aim was to create a political truce between science and religion.

What’s more, Gould (kinda) admitted this in various places.

Of course, Gould didn’t use the word “political” to describe NOMA. Instead, he — at least partly — saw it as being a diplomatic position. (In his own words, NOMA is “very practical”.)

It can safely be said that Gould would have denied any accusations of being motivated exclusively by politics and diplomacy.

For example, in a speech to the American Institute of Biological Sciences, Gould said the following:

“[T]he reason why we support that position is that it happens to be right, logically.”

Yet he immediately continued:

“But we should also be aware that it is very practical as well if we want to prevail.”

[Gould also stated that his position was not “a mere diplomatic stance”.]

Thus, Gould was hinting at (or simply stating) that there was a perfect and very convenient match between what is “right” and logical, and what is diplomatic.

How neat, tidy and convenient that is. Indeed, how political it really is.

Finally, if securing a truce between religion and science is so important, and it should be brought about (as the phrase has it) “by any means necessary”, then perhaps I shouldn’t have written this critical essay on Gould’s idea of non-overlapping magisteria.

********************************

Notes:

(1) The fact-value distinction is a minefield. See a critical account of Stephen Jay Gould’s own use of the distinction here.

(2) There is another way of making sense of Gould’s political diplomacy toward religion.

Take one of the reasons why many people on the Radical Left have become largely (sometimes completely) uncritical of religion.

For over a hundred years, millions of Marxists and/or communists held very strong and aggressive positions against religion. That was the case until the 1960s and beyond. Indeed, all this can be dated back to Karl Marx’s “opium of the people” and all that. It can also be said that if religion is a “mere epiphenomenon” of economic and political realities, then its claims can neither be true nor fully respected.

However, if religion is indeed the opium of all the oppressed who exist within capitalist systems (as well as “the sigh of the oppressed creature”), then there’s little point in getting angry with — or even critical about — religion and the religious. Indeed, the opposite may be a better political and strategic position for the those on the Radical Left.

So was this Stephen Jay Gould’s own position?

Some contemporary Marxists have also offered us more (so it’s argued) “sophisticated” and “nuanced” — or politically diplomatic and strategic — interpretations of what Marx and other communists said about religion.

In any case, things quickly changed.

I believe the main reason for that was demographics and ethnicity. It came to be seen that many religious people in Europe and America were not “white”. Thus, it also came to be seen that it may be (or is) politically dangerous to criticise the religions of people who aren’t white. More specifically, the term “racist” then came to be used against the critics of Islam (e.g., by the Socialist Workers Party and many other groups and individuals).

Of course, some critics of Islam are indeed racist.

The Guardian newspaper is a good example of this new trend on the Left.

Over the decades, the Guardian published very many articles which were strongly — sometimes fiercely — critical of Christianity. Then that changed — seemingly overnight. The Guardian (or at least a few Guardian journalists) came to realise that many religious people in the UK were Muslims. And most Muslims aren’t white. Thus, it concluded that attacks on Islam were often (sometimes always) what it called “racist”. (This all occurred quite recently — in the late 1990s and 2000s.)

This about-turn on religion as a whole was largely the result of the work of particular Guardian journalists. However, it also seems to have become the Guardian’s general editorial stance. (This new attitude toward religions is deemed to be more “nuanced” and “sophisticated” by those journalists and writers who expressed it.)

Of course, there are exceptions to this trend in the Guardian, as displayed by a handful of pieces which are still critical of religion.

More relevantly, Stephen Jay Gould himself would have certainly noted the ethnicity (or colour) of many religious people in the United States. And, to put it simply, he would have then concluded that this racial and religious reality had important political ramifications.

[The Guardian journalist Andrew Brown is a good example of all the above. See his ‘Why I don’t believe people who say they loathe Islam but not Muslims’. See also the paper ‘The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia’ by Steve Garner and Saher Selod, which explicitly states that the criticism of Islam is racist. Indeed, what came to be called “Islamophobia” was — and still is — widely deemed to be entirely racist by many of the people who use that term.]

My flickr account and Twitter account.

No comments:

Post a Comment