The philosopher Michel Foucault argued that (most? all?) people don’t realise that the epistemes they exist within determine their experiences, “discourse”, beliefs and even behaviour. (According to Foucault, epistemes constitute “the historical a priori”.)… So how did Foucault and similar theorists (e.g., Marx, etc.) escape from the conceptual schemes and/or epistemes they found themselves within? Indeed, did they really escape? More relevantly, do conceptual schemes and epistemes exist in the first place?

Firstly, the title above may be a little misleading to some readers. That’s mainly because the essay itself doesn’t discuss specific political positions or specific political/social groups. In other words, there’s no claim here that a particular set of people are (or are not) sheeple because they believe x or y. Instead, this essay is (to quote Donald Davidson) “on the very idea of a conceptual scheme”.

This explanation is given because it sometimes seems as if many politicised young people (mainly males under the age of 22 and teenagers) are accusing everyone else — i.e., outside their own political flocks — of being “sheeple” (see here).

So why is that?

It’s surely because such young people deem sheeple to be the mindless (as it were) members of various conceptual schemes and/or epistemes (i.e., as these schemes and/or epistemes are embedded in specific nations/states and societies)… Not that that these two particular technical terms (i.e., “conceptual schemes” and “epistemes”) are ever actually used by most of those who refer to other people as sheeple.

More relevantly, in this essay the term “conceptual scheme” is used in pretty much the same (largely non-political) way in which the American philosopher Donald Davidson (1917–2003) used it.

Davidson (in his paper ‘On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme’) wrote that conceptual schemes are “ways of organizing experience”, as well as “systems of categories that give form to the data of sensation”. More generally, they are “points of view from which individuals, cultures, or periods survey the passing scene”.

Yet despite just telling us what conceptual schemes are, Davidson didn’t actually believe that such things exist! [See my own essay, ‘There Are No Conceptual Schemes’.]

A more standard definition of a conceptual scheme is the following:

“The general system of concepts which shape or organize our thoughts and perceptions. The outstanding elements of our everyday conceptual scheme include spatial and temporal relations between events and enduring objects, causal relations, other persons, meaning-bearing utterances of others, and so on. To see the world as containing such things is to share this much of our conceptual scheme.”

Despite this definition, this essay is largely about Foucauldian conceptual schemes. It also notes Davidson’s earlier (critical) definitions of the notion.

More broadly, it can be argued that the belief in (or acceptance of) the very idea of a conceptual scheme (or at least the strong political and sociological stress on such a thing) led to a belief in linguistic relativity (or the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis). Indeed, it also — at least partly — led to various varieties of moral and political relativism generally. (Note, again, Davidson’s idea that conceptual schemes are “points of view from which individuals, cultures, or periods survey the passing scene”.)

All that said, conceptual schemes can either be seen as vague abstract entities, or, indeed, as real concrete entities.

This means that some of the conceptual schemes referred to in the following don’t strictly abide by any of Davidson’s own definitions and analyses. However, that doesn’t matter because his broad account will still give readers a way (or means) to discuss whether the entities provisionally deemed to be conceptual schemes — i.e., by other people — really do have such a determining and powerful impact on the minds of all those people who’re supposed to be under their spell. (Hence, the rhetorical use of the word “sheeple” in the title.)

It will now be seen that an episteme (at least as described by Michel Foucault) has various similarities with the notion of a conceptual scheme.

Michel Foucault on Epistemes

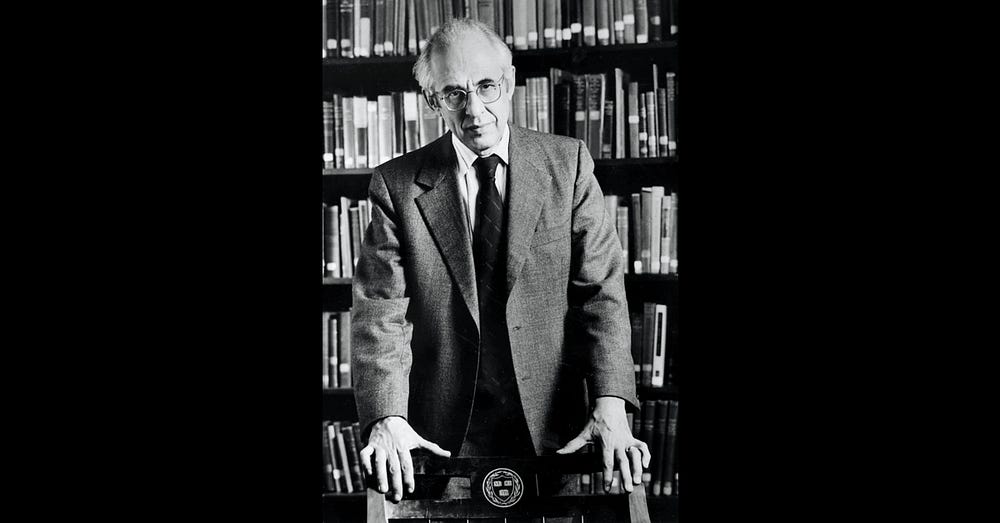

The French philosopher Michel Foucault (1927–1984) used the term épistémè in his book The Order of Things. He defined the word in the following way:

“[T]he historical a priori which i[n] a given period, delimits the totality of experience [of] a field of knowledge, defined the mode of being of the objects that appear in that field, provides man’s everyday perception with theoretical powers, and defines the conditions in which he can sustain a discourse about things that [are] recognised to be true.”

And elsewhere in the same book, Foucault also wrote:

“In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice.”

It seems clear that Foucault had a view of epistemes which made them deterministic in nature. (He did qualify, in various places, this charge of conceptual and cognitive — hence also political — determinism.) That is, Foucault believed that (most? all?) people don’t consciously adopt their epistemes. What’s more, they don’t realise (or know) that their epistemes determine their experiences, “discourse”, beliefs and even behaviour. Thus, according to Foucault, epistemes are (among other things) “the historical a priori”. That means that (if this term is taken in its almost Kantian sense) each episteme literally comes before experience (at least for a particular historical or social group) and therefore it forms and shapes all experience.

Kant was just mentioned in parenthesis a moment ago. Foucault himself used the phrase “historical a priori” (as already quoted) in homage to the 18th century German philosopher.

So let’s take Kant’s arguments for his own (as it were) conceptual scheme as true, at the same time as noting that it’s very different to a Foucauldian episteme.

It can be said that literally no one can escape from Kant’s mental and/or cognitive a priori categories and concepts. Indeed, in the language of 21st century neuroscience and cognitive science, that’s because whatever it is that’s responsible for our Kantian categories and concepts, it must be physically hardwired — i.e., from birth — into the brains of all human beings.

Thus, in the Kantian story, we must see objects as objects. We must see things in terms of cause and effect. And we must see things in terms of internal time and external space. Etc.

Thus, in a strict sense, some of the examples offered below can’t be a priori in this strict Kantian sense. (This is true, for example, of class consciousness.) The closest which some conceptual schemes (if that’s a suitable term at all) come to the Kantian a priori include Chomsky’s universal grammar, the deep structures of Lacan and Lévi-Strauss, Freud’s subconscious, etc. However, even deep structures were seen to be limited to specific cultures at specific times. (There were also, admittedly, deemed to be “universal” and “timeless” threads to such structures.) And each Freudian subconscious is specific to each individual person. (Here again, there are said to be universal and timeless threads to the human subconscious.)

To return to Foucault.

A Foucauldian episteme is far more broad (as well sociological, political and historical) than Kantian a priori concepts and categories. Indeed, Kant’s categories and concepts (if taken to be real things) apply to all human beings at all times (i.e., they can’t constitute Foucault’s historical a priori). That said, some of Foucault’s statements about epistemes do have Kantian resonances.

For example, according to Foucault, an episteme defines “the mode [] of the objects that appear”. It also “determines the totality of experience”. And so on. However, Foucault appeared to have overstepped the Kantian mark when he argued that an episteme determines certain epistemic constraints on our “discourse about truth”.

[Note here that the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget argued — see here — that Foucault’s use of the term épistémè was similar to Thomas Kuhn’s notion of a paradigm. Perhaps, too, R.G. Collingwood’s notion of historical “absolute presuppositions” chimes in with Foucault’s historical take on epistemes.]

So what about Foucault’s very own escape from what he called the “contemporary episteme”?

How Did Foucault Escape From His Episteme?

In 1971, Michel Foucault wrote the following:

“[] I am trying to grasp the implicit systems which determine our most familiar behaviour without our know it [] to show the constraints they impose upon us. I am therefore trying to place myself at a distance from them and to show how one could escape.”

Note also here the Marxist’s escape from false consciousness or Karl Marx’s own escape from the “bourgeois ideology” of both his own family and his overall background. (Interestingly, Foucault once wrote the following: “Marxism exists in nineteenth-century thought like a fish in water: that is, it is unable to breathe anywhere else.”)

In any case, perhaps some people don’t actually want to escape (or transcend) their conceptual scheme or episteme. That may be because they might have reflected on the concepts, beliefs, norms, etc. of their conceptual scheme, and not found them wanting. However, Foucault seemed to have assumed that because people were (as it were) happy with their episteme (or conceptual scheme), then they mustn’t in fact have recognised that they’re living, working and thinking within one.

So how did Foucault himself escape from his own episteme?

Perhaps this isn’t a philosophical question. Perhaps it’s a question about Foucault himself. That is, this may not be about how Foucault philosophically and/or intellectually transcended his own episteme (note the quote earlier). Instead, it may about why he believed he had done so.

In the past there have been many people with such special powers. Such people argued there were no alternative ways of escape other than their own. What’s more, if someone believed that he has escaped via another route, then he or she mustn’t have really escaped at all. Indeed, it wouldn’t be a genuine episteme (or the subconscious, or class consciousness) otherwise. Thus, it’s no use stressing conceptual schemes or epistemes if people can escape from them willy-nilly.

All this, of course, raises a self-referential question. Namely:

How did such philosophers and theorists (such as Foucault, Marx, Freud, etc.) themselves escape from their conceptual schemes or epistemes?

Did they do so by choosing the true path of escape?

This means that if the rest of us don’t choose the true path (specified by Foucault or, say, Marxists), then we can’t (by definition) have escaped.

That said, perhaps some of these philosophers and theorists happily acknowledged that at least a small number of people can be conscious of their own conceptual scheme. However, unless they’re conscious of it in the true way, then they can’t (really) escape (or transcend) it at all.

This means that it’s not enough to have knowledge, insight and intelligence about our own conceptual scheme: we must have true (i.e., Foucauldian or Marxist) knowledge, insight and intelligence about it. On the other hand, even if a follower of Foucault (or Marx) were an intellectual imbecile and had only being a loyal reader of Foucault’s (Marx’s) works for one single month, then he could still escape his conceptual scheme simply by fully embracing Foucault’s (or Marx’s) analyses, ideas and theories. (Personally, I experienced such a thing many times in my late teens and early twenties.)

As with this essay itself, the American philosopher Hilary Putnam (1926–2016) came at the issue of a conceptual scheme from an angle very different to both Donald Davidson and Michel Foucault.

Hilary Putnam on Conceptual Schemes

Hilary Putnam argued that the very fact of recognising (let alone criticising or rejecting) a conceptual scheme surely means that it has, at least to some extent, been (to use Putnam’s word) “transcended”.

In more detail.

According to Putnam (in his paper ‘Why Reason Can’t Be Naturalised’), the fact that persons can criticise a (or their own) conceptual scheme casts doubt on any notion of such an (abstract) self-contained and self-enclosed structure.

Putnam himself mentioned Michel Foucault. [See also Putnam’s ‘Beyond Historicism’ in his Philosophical Papers.]

According to Putnam, Foucault and other conceptual-scheme determinists (words Putnam didn’t use) claim that we “mechanically apply cultural norms”. In actual fact, however, Putnam argued that many people “interpret” and “criticise” them. (Well, Foucault himself certainly did.)

Putnam’s critique of such determinism — he referred specifically to rationality — can be expressed in this way:

a conceptual scheme

↓

determines

↓

rationality

↓

and rationality

↓

transcends (through criticism, self-reflection, etc.)

↓

that conceptual scheme

Putnam’s internal realism can also be applied to the notion of a conceptual scheme — and the parallel stress on language — in the following way:

position A (which Putnam says is “language-determined”)

↓

gives rises to

↓

position B (which is also language determined)

↓

Thus, “we make new versions [of language] out of old ones”.

However, one might have asked Putnam this question:

If a conceptual scheme — or a given language — is so easy to transcend, then why talk in terms of a conceptual scheme at all?

(This seemed to have been at least part of the gist of Davidson’s argument.)

It can be doubted that Putnam did argue that it’s easy to transcend a conceptual scheme. It may take a lot of hard work. Alternatively, such transcendence may be — at least partly — fortuitous.

The point is, however, that not all the conceptual schemes (or epistemes) are equivalent to, say, the a priori categories and concepts of Kant (or, say, to Chomsky’s language faculty). In non-Kantian terms, then, conceptual schemes can be — or actually are — contingent. Indeed, Foucault himself argued that epistemes are contingent in that they might have been otherwise. However, once an episteme becomes a (as it were) reality, then it non-contingently determines experience, “discourse”, and knowledge.

(Remember here that Foucault argued the following three things: (1) “In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one episteme.” (2) That an episteme determines the “conditions of possibility of all knowledge”. (3) That a conceptual scheme “delimits the totality of experience [of] a field of knowledge”.)

Of course, there are lots of contingent psychological, social and political phenomena which are, nonetheless, long-lasting and very hard to escape. However, this doesn’t make them any less contingent.

On the other hand , many things which were once deemed to be necessary or a priori turned out to be no such thing at all. And, of course, some philosophers have questioned the very existence of any form of a priori or necessity.

Thus, Foucault’s own notion of a historical a priori must itself become — and indeed has become — a victim of history and of philosophical criticism.

My flickr account and Twitter account.

No comments:

Post a Comment