Religious/“spiritual” commentators, New Age “scientists”, and self-described “anti-materialists” often cite the case of Wolfgang Pauli and his (what they call) “mystical” views. They also note that Pauli admired — and was inspired by — the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung. Yet Pauli was a physicist —indeed, a great physicist. So it’s not much of a surprise that virtually none of his writings on mystical matters were published in his lifetime — certainly not as academic papers or books. However, various books on Pauli’s mysticism and his relationship with Jung were published long after his death in 1958.

To put it at its most extreme: a person may be serial killer and still be a great scientist. Similarly, a person may (i.e., in his private life) believe in pixies, white/black supremacy, or alien lizards and still be a great scientist.

Indeed, there’s a long list of great scientists and mathematicians who held very peculiar views outside their scientific and mathematical work. [See ‘The ‘Maddest’ Scientists In History’, which doesn’t even include Kurt Gödel starving himself to death.]

To state the obvious: these people weren’t great scientists and mathematicians for the stuff they believed, theorised about and stated outside their respective scientific and mathematical work.

In even more simple terms. These scientists and mathematicians were flesh and blood human beings. Thus, they had particular psychologies, particular backgrounds, particular prejudices, and particular quirks.

But none of that should be a surprise.

As for the particular psychology, particular background, particular prejudices and particular quirks of Wolfgang Pauli himself.

Even fans of Pauli’s “mystical” views (i.e., his views outside physics) stress his personal details.

For example, Gerald R. Baron (to be discussed later) writes:

“In 1930 [] one of the pioneers of the rapidly advancing science of quantum mechanics had a personal crisis. Troubled by a divorce and his mother’s suicide, he consulted one of the leading lights of the new science of psychology [Carl Jung].”

Elsewhere, Baron also wrote:

“Pauli and Jung came together in late 1930 after Pauli divorced his cabaret-singer wife and Pauli’s mother committed suicide. His personal crisis and cry for help from one of the most famous psychoanalysts of his time [].”

To readers firmly outside both religion and psychoanalysis, this may simply seem like a rather typical example (even a caricature) of a person embracing Jungian psychology and/or mysticism due to very negative personal circumstances.

We can add to all that the fact that Pauli’s father had even encouraged his son to develop an interest in Jung. And, in a more personal light, Pauli loved having his dreams analysed.

So it can now be argued that had Pauli lived at any other time, and in any other environment, then there would have been a very strong chance that he simply wouldn’t have been attracted to the work of Carl Jung. Philosophically (or logically) speaking, of course, had Pauli been born at any other time, and lived in any other environment, then such a person wouldn’t actually have been Wolfgang Pauli in the first place.

In any case, now let’s place Pauli’s mysticism in its philosophical context.

Wolfgang Pauli (just like Erwin Schrödinger) was influenced by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). And, of course, Schopenhauer’s own views were influenced by “Eastern” religions. [See here.]

So what of the broader historical context?

In his ‘Mysticism in quantum mechanics: the forgotten controversy’, the historian of science Juan Miguel Marin explains the culturally contingent nature of this fixation with mysticism within a context which is wider than just Pauli himself.

In detail.

Marin stresses that up to World War Two, quantum mechanics existed in a mainly German — and Austrian (?) — context. And, in that context, there was a “mystical zeitgeist”. Yet, Marin adds, all that ended in the 1950s, when physics became (as he puts it) “Anglo-American”.

[Sure, a historian or a sociologist can now say that this Anglo-Saxon “hegemony” also expresses cultural and historical contingency when it came to physics.]

Marin then tells us that this mystical zeitgeist was a culturally short-lived phenomenon. He also tells us that Schrödinger’s lectures of 1958 were virtually the end of mysticism in physics. Needless to say, this doesn’t also mean that there weren’t isolated “mystical physicists” still around after 1958. (When the American hippies arrived in the mid-1960s, then the fashion for mysticism and “Eastern” religions arose again.)

In any case, Wolfgang Pauli was a great physicist who also believed in mysticism (see ‘Quantum Mysticism: Gone but Not Forgotten’), the ideas and theories of Carl Jung, numerology (see ‘Cosmic numbers: Pauli and Jung’s love of numerology’), synchronicity, etc. More relevantly, Pauli used the term “lucid mysticism” to refer to his own general stance on these matters. (That stance being the “synthesis between religion and rationality”.)

Yet despite all the above, it should be kept in mind here that Pauli had very little (almost nothing) published on these mystical subjects. [See note 1.]

False Authority: Name-Dropping Various “Great Scientists”

If writers and commentators can mention a great scientist like Wolfgang Pauli (or, indeed, Erwin Schrödinger) to back up their prior philosophical and/or religious views, then other “anti-religious” commentators and writers can quote other great scientists to back up their own prior anti-religious, anti-Jungian, etc. positions too.

Who knows, perhaps the fans of Pauli’s mysticism would say that this argumentative toing and froing is a good thing.

What’s more, for every Pauli, there are hundreds — or even thousands — of scientists who would have no time at all for Jung, religion, mysticism, synchronicity, idealism, etc. Indeed, some of these names also include great scientists. [See note 2 for a long list.]

As it is, it’s probably wise not to rely on scientists (even the great ones) to back up (or at least attempt to clinch) any philosophical views or positions (say, for or against panpsychism, idealism, etc.). And that’s mainly because these views or positions aren’t actually within physics in the first place.

That said, philosophical “materialists”, atheists, etc. could name-drop all sorts of scientists to back up their own materialism, atheism, etc.

Perhaps some of them do.

In more detail.

Name-dropping (or name-checking) various artfully-selected scientists doesn’t do much of a job when it comes to attempting to sell a particular philosophical and/or religious (or “mystical”/“spiritual”) position. Or, at the very least, name-dropping on its its own doesn’t do much work.

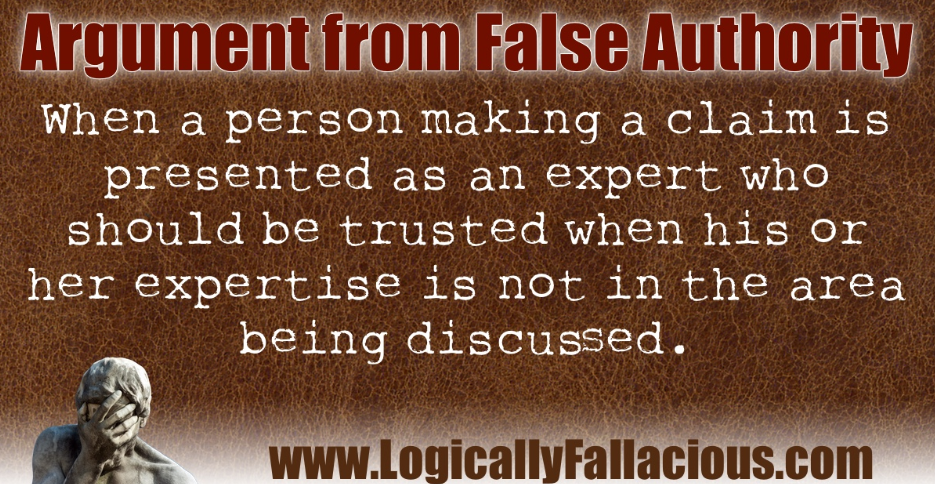

What’s more, doing so is often simply to indulge in the false authority fallacy.

The philosophers Carl Cohen and Irving Copi, for example, captured the case of quoting and mentioning physicists like Wolfgang Pauli, Albert Einstein and Erwin Schrödinger (i.e., on subjects outside physics) when they said that the false authority fallacy occurs

“when the appeal is made to parties having no legitimate claim to authority in the matter at hand”.

Copi and Cohen then added:

“[W]hen an authority is appealed to for testimony in matters outside the province of that authority’s special field, the appeal commits the fallacy of argumentum ad verecundiam.”

More relevantly, take the words of Gerald R. Baron on Wolfgang Pauli and Carl Jung.

Gerald Baron on Wolfgang Pauli and Carl Jung

Gerald Baron wrote:

“What is most important for our discussion here is how so many of the great minds of yesterday and today are converging in their thoughts about these questions.”

Sure.

Many great minds converged on many other “questions” too — and some of their answers were downright false. They also converged on mutually-contradictory positions and theories.

Baron then does the same kind of thing (i.e., which he’d just done with Wolfgang Pauli) with John Polkinghorne (i.e., with the addition of the “Sir” before his name).

Baron tells us that Polkinghorne was “one of Britain’s greatest theoretical physicists”. Indeed, Polkinghorne was a physicist who also

“saw a strange similarity between the role that consciousness plays in affecting physical reality — the quantum measurement ‘problem’ — and the interchange between the unconscious and conscious in the mind”.

This, again, just seems like an attempt to get some well-known physicists on board the mystical or religious train. And, as already stated, for every Pauli or Polkinghorne, there are a hundred — or even a thousand — physicists (some great ones too) who would never state some of the things that Pauli and Polkinghorne stated.

All that said, the words “scientific heretics” crop up a lot in these discussions. In other words, because Pauli, Polkinghorne, Schrödinger, etc. attempted to tie physics to religion (or to mysticism), and most other scientists don’t do so, then the former are often classed as “heretics” by their supporters and fans. [See my ‘Rupert Sheldrake’s ‘Heretical’ Caricatures of Scientists and Science’.]

In any case, is Sir Polkinghorne a “great physicist” anyway?

Rather, wasn’t he just an fairly important physicist working in the strict and limited context of British physics between the late 1950s to the 1970s? Indeed, in the Wiki article on Polkinghorne, almost all of it is about him being a “leading voice explaining the relationship between science and religion”.

Of course, it obviously can’t be denied that Polkinghorne wrote academic papers on physics (as with every physics postgraduate who has ever lived), and that he also had some kind of institutional role within parts of British physics. However, none of this amounts to making him a great physicist. Again, most of the entries on — and short accounts of — Polkinghorne don’t spend any time at all on his purely physics-based ideas and theories. Instead, religion is mentioned in almost every paragraph.

So it can also be strongly suspected that Gerald Baron would never have felt the need to mention Polkinghorne (let alone call him “one of Britain’s greatest theoretical physicists”) if he couldn’t also connect him to his own philosophical and religious views. In other words, it can be doubted that Baron would have had any interest at all in Polkinghorne exclusively as a physicist.

Baron concludes by stating the following:

“If nothing else, the collaboration of a Nobel laureate physicist [Wolfgang Pauli] and a leading thinker on the mind and human experience [Carl Jung] demonstrates the value of approaching the question of reality in a holistic way, meaning from more than one field of study.”

So how deep and wide should such holism go?

Should everything under the sun be mentioned when discussing a particular subject or problem? (Even mutually-contradictory views?)

Would it be holistic to mention urban architecture when writing about set theory? What about horticulture when writing about quantum entanglement? Or soccer when discussing genetic mutations?

Indeed, holism can result in an obvious free-for-all (i.e., a kind of philosophical free improvisation) in which anything can be connected to anything if the poetic, analogical and/or religious urge to do so arises.

Sure, the examples above may seem extreme or even simple jokes. However, Pauli himself did connect particles to what he called “souls”. [See here.]

[The technical details of Pauli’s (as it were) scientific-mystical theories will be discussed in a future essay.]

Part Two

Wolfgang Pauli’s Positivism

Those commentators and writers who emphasise Wolfgang Pauli’s mysticism won’t also be too keen on stressing his (extreme) positivism (i.e., his general anti-metaphysical attitude) too. Or, at the very least, they may say that Pauli was a positivist only up to a point: that point being (more or less) when he met Carl Jung.

This general standpoint is put by the science historian Karl von Meyenn when he wrote:

“Pauli grew up under the influence of Ernst Mach, but — like Einstein — he turned away from the radical positivism of most of his contemporaries quite early.”

Arguably, Pauli didn’t turn away from positivism “quite early” at all. He did so when he was 32. And that was after much of his important work in physics had already been done. What’s more, Pauli’s well-known positivist quote about “how many angels are able to sit on the point of a needle” was written in 1954, some 22 years after first meeting Carl Jung. (This will be discussed again in a moment.)

Various articles and papers which reflect upon Pauli’s positivism basically argue that he was a positivist until (roughly) 1932 — when he was 32. In Pauli’s own words:

“It so happened that my father, then intellectually completely under Mach’s influence, was very friendly with his family. Mach had affably expressed his willingness to play the role of my godfather. He was, no doubt, a stronger personality than was the Catholic priest. The result seems to be that, in this way, I was baptized as ‘Antimetaphysical’ instead of Roman Catholic.”

And, in a letter from 1953, we can even read Pauli mentioning Mach and Jung in the same breath. He wrote:

“I imagine him [Ernst Mach] amiably shaking your [Carl Jung’s] hand, welcoming your particular definition of physics as a pleasing, if somewhat belated, sign of insight. [] Finally, he expresses his satisfaction that you have banished all metaphysical judgments (as he was fond of saying) ‘into the shadow realm of a primitive animism.’”

So most of Pauli’s important work was done in that pre-1932 period. Of course, that isn’t also to say that Pauli didn’t do substantial work after 1932. For example, there was his spin–statistics theorem of 1940, and his CPT theorem of 1954. (It’s not clear to me, as a non-physicist, how much of these theorems was purely Pauli’s work.)

So it’s worth noting here that at the age of 21, the precocious Pauli had his well-known article on special and general relativity published. (It was published in the Encyclopedia of the Mathematical Sciences, and it now appears as a book called Theory of Relativity.) This is an article of 237 pages, and 394 footnotes. Many commentators still regard it as one of the best things ever written on both relativity theories.

But let’s cite more details on Pauli’s positivism.

In an interview published in In Our Time: Celebrating Twenty Years of Essential Conversation), the particle physicist Frank Close said:

“[Ernst Mach] was a philosopher who influenced the Vienna Circle of logical empiricists with his well-known anti-metaphysical attitude. [] When Pauli was born, Mach was invited to become his godfather. The story goes, that many years later, Pauli said, jokingly, that, because Mach was such a great influence on him, he was baptised not so much Catholic but anti-metaphysical, a line of reasoning that remained for the rest of his career.”

Thus, it was no surprise that Pauli once stated (in a letter to Max Born) the following often-quoted words:

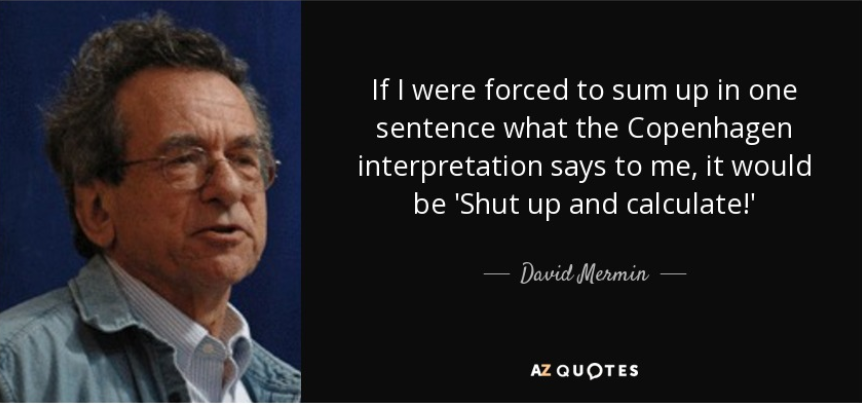

“[O]ne should no more rack one’s brain about the problem of whether something one cannot know anything about exists all the same, than about the ancient question of how many angels are able to sit on the point of a needle.”

It must be noted here that Pauli wrote these words in 1954 — long after the “quantum revolution” of the 1920s and 1930s, and some 22 years after he first first met Carl Jung.

The passage from Pauli directly above can be interpreted as him shouting “shut up and calculate!” long before these well-known words were ever uttered (i.e., by N. David Mermin in 1989).

So now take Carl Jung’s idea (as expressed by Gerald R. Baron) that “the unconscious is in the realm of objective reality while the conscious [mind] is not — it is subjective”. (It’s worth noting here that Pauli offered criticisms of Jung’s work, particularly of the notion of synchronicity.)

In the light of Jung’s reference to “objective reality”, it can be said that Pauli rejected the opposition between objective reality itself (or “ultimate reality”), and what we can can know about reality (as did Niels Bohr). In other words, knowing “how Nature is” amounts to no more than a metaphysician’s dream. All we actually have is “what we can say about Nature”. And, at the quantum-mechanical level at least, what we can say is what we can say with the mathematics — in conjunction with experiments, tests, observations, etc. Consequently, just about everything else is interpretational, analogical and/or imagistic in nature. Indeed, the analogical, imagistic and interpretational stuff can — and often does — mislead us. It also causes endless insoluble controversies.

More relevantly, Jung’s theories and ideas seem to fall into all the (metaphysical) traps which Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and, indeed, Wolfgang Pauli warned others about.

In terms of Pauli himself.

Perhaps Pauli came to believe (i.e., roughly after 1932) that only physicists (as physicists) should shut up and calculate, or stop talking about objective reality. However, physicists in conjunction with, say, Carl Jung shouldn’t shut up. Alternatively, physics (qua physics) has nothing to say about objective reality. However, physicists working with mystics, psychanalysts, theologians, religious leaders, etc. may speak freely about objective reality.

All that said, defenders of Pauli may point out that his mysticism, the ideas of Jung, etc. don’t contradict (or clash with) Pauli’s prior physics — or, indeed, contradict (or clash with) any (established) physics of any kind.

In any case, there’s no doubt at all that Pauli himself did attempt to tie his physics to his mysticism.

So tying physics and mysticism together doesn’t make them the same thing. More importantly, it doesn’t mean that we have to accept all attempts at tying these two very different things together.

So it’s complicated.

In terms of examples. Biographers and commentators have argued that Pauli drew on nonlocality, complementarity, and the observer effect in order to (as it were) back up his mysticism.

More specifically, physicist Thomas Filk has argued that quantum entanglement (“a particular type of acausal quantum correlations”) was taken by Pauli to be “a model for the relationship between mind and matter in the framework [which] he proposed together with Jung”.

[As already stated, the technical details of Pauli’s scientific-mystical theories will be discussed in a future essay.]

More simply, quantum entanglement was deemed to be a physical phenomenon which “most closely represents the concept of synchronicity”…

However, note the words “model” and “represents” in the quoted lines above.

As far as can be seen, all that we have here is (often vague) talk of resemblances, analogies, metaphors, (Gerald Baron’s) “strange similarities”, etc. And all that is stock in trade when it comes to writers of “woo” and “New Age science”. Of course, this isn’t (necessarily) to argue that Pauli’s mystical writings are at the same level as all this very amateur stuff. However, perhaps we still merely have resemblances, metaphors, analogies, strange similarities, etc. between the theories and details of physics, and all the popular (mystical) stuff which is firmly outside physics.

Notes:

(1) As with most of the other great scientists endlessly memed and mentioned (such as Einstein, Schrodinger, Planck, etc.) to back up mystical and religious views, Wolfgang Pauli didn’t actually write any academic papers on Carl Jung, mysticism, etc. In other words, for every quoted passage on Jung, etc., Pauli wrote entire papers on physics which never mention any of this mystical stuff.

This situation is summed up by John R. Gustafson in the following words:

“Because Pauli was in a difficult individuation process during his early years, his own writings on philosophy tend to be sparse and often contradictory.”

The science historian Karl von Meyenn also makes a strong distinction between Pauli’s papers on physics, and the rest of his writings.

For example, in the following passage (from a paper called ‘Wolfgang Pauli’s Philosophical Ideas Viewed from the Perspective of His Correspondence’), Meyenn writes:

“While his publications present the results of more or less longsome searches for insight, his methodical flow of work and the gradual emergence of understanding become visible only in his rich correspondence.”

Indeed, Gerald R. Baron (mentioned earlier) admits that he’s not relying on Pauli’s books and academic papers on Jung, synchronicities, etc. And that’s simply because he didn’t write any. Instead, Baron refers to “collaboration” between Pauli and Jung which included “many letters and conversations over the years”. What’s more, most of the other writers who emphasise Pauli’s mysticism and his belief in Jung’s ideas also stress his “correspondence”.

It’s also worth noting that the popular books Writings on Physics and Philosophy and Atom and Archetype weren’t actually written as books by Wolfgang Pauli. Instead, these books are collections of Pauli’s articles and letters, which were written over many years. (Writings on Physics and Philosophy was edited and put together by Charles P. Enz and Karl V. Meyenn, and published in 1994. Atom and Archetype was edited by C. A. Meier, and published in 2014.)

(2) For example, Pierre and Marie Curie, Peter Higgs, Paul Dirac, Richard Feynman, Enrico Fermi, Murray Gell-Mann, Gerard ‘t Hooft, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Louis de Broglie, John Bell, Steven Weinberg, etc. etc. etc. never had any time for any mystical and/or religious stuff. What’s more, they’ve all also been classed as “atheists” by their critics.

No comments:

Post a Comment