The critics of both panpsychism and integrated information theory (IIT) rely on an implicit— although sometimes explicit — strong connection which they make between intelligence and consciousness. In basic terms, then, they believe that because very basic entities can’t be deemed to be intelligent, then they can’t be deemed to instantiate consciousness either.

(i) Introduction

(ii) Thermostats, Computers and Animals

(iii) According to Seth, Chalmers and Penrose, Functionalism Fails

(iv) John Searle on Biological Brains

Without actually mentioning panpsychism and integrated information theory (IIT), the British neuroscientist Anil Seth states the following:

“This is the assumption that consciousness and intelligence are intimately, even constitutively, linked: that consciousness will just come along for the ride.”

Now let’s take an extreme version of this position.

If intelligence and consciousness (with a stress on the former) are necessarily linked, then (depending on how “intelligence” is actually defined in the first place) thermostats can’t be conscious. And neither can ants, mice and even human babies.

Seth draws his own conclusions from this when he continues with these words:

“[T]he tendency to conflate consciousness with intelligence traces to a pernicious anthropocentrism by which we over-interpret the world through the distorting lenses of our own values and experiences. *We* are conscious, *we* are intelligent, and *we* are so species-proud of our self-declared intelligence that we assume that intelligence is inextricably linked with our conscious status and vice versa.”

Seth seems to pick up on a Cartesian strand here when he adds the following warning:

“If we persist in assuming that consciousness is intrinsically tied to intelligence, we may be too eager to attribute consciousness to artificial systems that appear to be intelligent, and too quick to deny it to other systems — such as other animals — that fail to match up to our questionable standards of cognitive competence”

It’s not entirely clear that any collective “we” has ever “conflate[d] consciousness with intelligence”. Perhaps only a single philosophical tradition — i.e., Cartesianism — did so. However, it’s still of up for debate how much of an influence that tradition had outside of philosophy and science.

In addition, not all other cultures and traditions — i.e., outside the West — have had benevolent and sympathetic attitudes to all animals. Added to that is the fact that individuals or collectives can be cruel to animals, deny them dignity and worth, etc. and still believe that they are indeed conscious, and, to a degree, even intelligent.

So there’s a danger of conflating Descartes’ own technical and somewhat philosophically-arcane position on animals, with what Western “folk” believed. [See Note 1.]

To sum up. It’s hard to believe that there are any strict Cartesians nowadays. Thus, anthropocentrism itself may not be as big a problem as Seth believes.

It depends…

It depends on the philosophical ism being discussed, and also on what particular philosophers and scientists have to say on the matters in hand.

All that said, and as ever, much of this depends on what’s meant by the words “consciousness” and “intelligence” in the first place!

Thus, if the word “intelligence” is taken (as Seth puts it) “anthropocentrically”, then we’re driven to a Cartesian position which denies most (even all?) animals consciousness. From a different direction, we’re also driven to a position which laughs at panpsychists for supposedly believing that stones or atoms “think”. [See my ‘Sabine Hossenfelder Doesn’t Think… About Panpsychism’.]

Thermostats, Computers and Animals

Against both anthropomorphism and Cartesianism, there’s a passage from Anil Seth (which doesn’t express his own position) which actually widens the domain of consciousness, rather than narrows it. However, even though it widens it to all animals, it doesn’t also do so to computers, robots, thermostats, etc. Seth writes:

“For some people — including some AI researchers — anything that responds to stimulation, that learns something, or that behaves so as to maximise a reward or achieve a goal is conscious.”

Thus, according to this account, thermostats may not be deemed to be conscious because they don’t — again, depending on definitions — learn anything, and they don’t do anything to maximise a reward or achieve a goal…

However, thermostats do respond to stimulation.

In any case, Seth’s account of consciousness above can be applied to literally all animals.

So is this an account which leaves out intelligence?

Or is responding to stimulation, learning something, and behaving so as to maximise a reward or achieve a goal not only constitutive of being conscious, but also of being intelligent?

Indeed, does it matter?

Which sets of data and arguments could possibly help us decide which is the best term (i.e., “intelligent” or “conscious”) to use here?

Still, Seth warns us that consciousness and intelligence are often juxtaposed. Yet they’re sometimes being juxtaposed in such a way (i.e., in the passage above) so as to work against anthropocentrism, and toward a widening of the domains of both intelligence and consciousness.

According to Seth, Chalmers and Penrose, Functionalism Fails

Anil Seth argues that functionalism is at the heart of both AI theory generally, as well as being at the heart of the belief that intelligence (or at least “intelligent behaviour”) and consciousness are intrinsically connected.

So first things first.

According to Seth’s account of functionalism,

“what matters for consciousness is what a system *does*”.

What does the relevant system do?

In this case, it “transforms inputs into outputs”. And if it does that “in the right way”, then, according to some functionalists, then “there will be consciousness”.

Thus, on this definition, a thermostat must be conscious — at least to some degree…

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers seems to agree.

In his ‘What is it like to be a thermostat?’, Chalmers writes:

“[Thermostats] take an input, perform a quick and easy nonlinear transformation on it, and produce an output.”

What Chalmers adds to this story, however, is the important notion and reality of information. [See here.] However, let’s just say here that ants and viruses take inputs too, and they perform quick and easy nonlinear transformations on such inputs, to produce outputs. (It can be doubted that a thermostat’s transformations are, in fact, nonlinear.)

So what about a paramecium and its own inputs and outputs?

The mathematical physicist Roger Penrose writes:

“For she [a paramecium] swims about her pod with her numerous tiny hairlike legs — the cilia — darting in the direction of bacterial food which she senses using a variety of mechanisms, or retreating at the prospect of danger, ready to swim off in another direction. She can also negotiate obstructions by swimming around them. Moreover, she can apparently even learn from her past experiences [].”

Chalmers has referred to proto-experiences when discussing a thermostat (although not actually quoted doing above), and here we have Penrose using the unadulterated word “experiences” in reference to a paramecium.

As already stated, functionalists stress… well, functions. In other words, they stress what systems do. Thus, functionalists also stress substrate-independence. Yet, as just mentioned, Penrose is actually stressing biology itself.

In more detail.

Penrose believes that ants are one step ahead of computers and other artificial entities when he claims that the

“actual capabilities of an ant seem to outstrip by far, anything that has been achieved by the standard procedures of AI”.

The molecular biologist, biophysicist and neuroscientist Francis Crick also argued that the study of consciousness must be a biological pursuit.

According to Crick, psychologists (as well as philosophers) have

“treated the brain as a black box, which can be understood in terms merely of inputs and outputs rather than of internal mechanisms”.

The biologist, neuroscientist and Nobel laureate Gerald Edelman (1929- 2014) is also said to have held the position that the mind

“can only be understood from a biological standpoint, not through physics or computer science or other approaches that ignore the structure of the brain”.

All this brings us to the more (philosophically) detailed account of these issues as offered to us by the American philosopher John Searle.

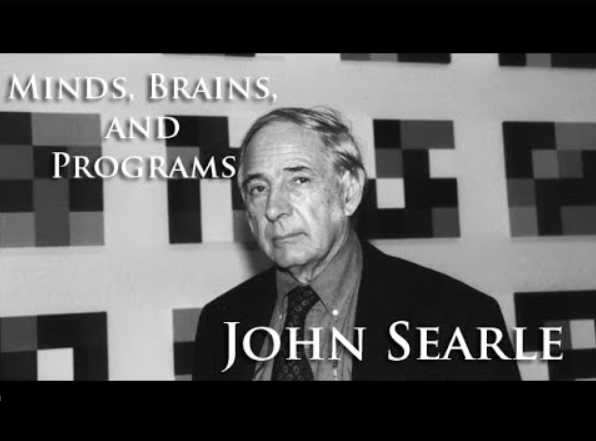

John Searle on Biological Brains

Searle’s basic position is that if functionalists ignore the physical biology of brains and nervous systems, and, instead, focus exclusively on syntax, computations or functions, then that will lead to a kind of 21st century mind-body dualism. What he means by this is that in much AI theory and functionalism there’s a radical disjunction created between the actual physical reality of the brain and how we explain — or account for — consciousness (as well as for intentionality and the mind generally).

Searle himself wrote the following words:

“I believe we are now at a point where we can address this problem as a biological problem [of consciousness] like any other. For decades research has been impeded by two mistaken views: first, that consciousness is just a special sort of computer program, a special software in the hardware of the brain; and second that consciousness was just a matter of information processing. The right sort of information processing — or on some views any sort of information processing — would be sufficient to guarantee consciousness. [] it is important to remind ourselves how profoundly anti-biological these views are. On these views brains do not really matter. We just happen to be implemented in brains, but any hardware that could carry the program or process the information would do just as well. I believe, on the contrary, that understanding the nature of consciousness crucially requires understanding how brain processes cause and realize consciousness. ”

He continued:

“Perhaps when we understand how brains do that, we can build conscious artifacts using some nonbiological materials that duplicate, and not merely simulate, the causal powers that brains have. But first we need to understand how brains do it.”

To Searle himself, it’s mainly about what he calls “causal powers”.

This refers to the fact (or possibility) that a certain level of complexity is what’s required (as against panpsychism, and perhaps against integrated information theory too) to bring about those causal powers which are necessary for consciousness (as well as for intentionality and mind generally).

Despite that, Searle never argues that biological brains are the only things capable — in principle — of bringing about consciousness and (genuine?) intelligence. (Therefore, in Searle-speak, semantics.) He only argues that biological brains are the only things known to exist which are complex enough to do so. Again, Searle doesn’t believe that only brains can give rise to minds. Searle’s position is that only brains do give rise to minds. In other words, Searle is emphasising an empirical fact. However, he’s not also denying the logical, metaphysical and even natural possibility that other things can bring forth consciousness and intelligence.

Note:

It can be argued that Descartes’ view on animals filtered down to the folk. On the other hand, it can also be argued that Descartes himself latched onto preexisting (Christian?) views about animals.

It’s also worth noting here that Descartes stressed mind, not consciousness itself.

(*) See my ‘Neuroscientist Anil Seth Links Panpsychism To Integrated Information Theory’ and ‘Anil Seth: Consciousness ≠ Integrated Information’.

No comments:

Post a Comment