The American writer and journalist Nicholas G. Carr offers his readers an interesting take on the philosophical position of mysterianism. His central point, however, seems obvious: that human beings aren’t omniscient. Of course, mysterians never use the strong word “omniscient” in this context. Yet that still seems to be the upshot of their position. Still, not many people would deny that there are many consequences of human beings (i.e., ourselves) having “limited intellect”.

It may seem to some readers that the American writer and journalist Nicholas G. Carr is simply putting the position of mysterianism without thereby committing himself to it. However, he did commit himself to it when he originally posted the piece concentrated upon in this essay. He wrote:

“[B]eing an amateur Mysterian myself, I continue trying to spread the good word.”

Before that, Carr had also written the following words:

“You don’t make friends by telling people they’re not as smart as they think they are. And you definitely don’t make friends by telling all of humanity that it’s not as smart as it thinks it is. That’s why the philosophical school of Mysterianism has never caught on with the public.”

Human Beings Aren’t Omniscient!… Really?

When Nicholas Carr states that mysterians “propose that human intellect has boundaries” he shows us that they’re stating the obvious… Of course human intellect has boundaries. If that weren’t the case, then human beings as individuals, or collectively, would literally be omniscient.

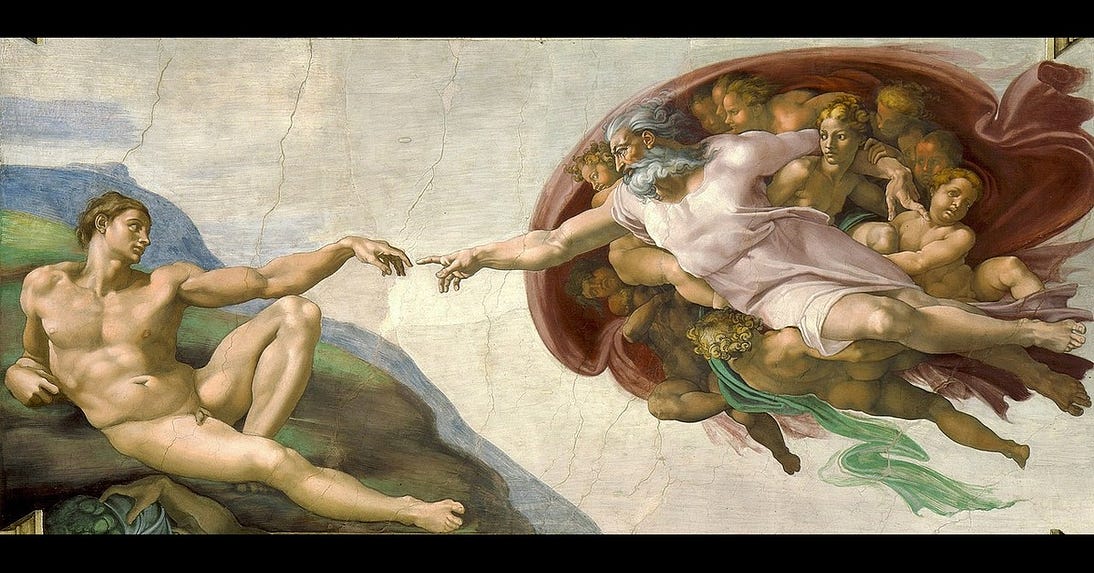

In any case, almost no one believes that the human intellect has no boundaries. Indeed, it’s even hard to understand what a limitless intellect could even be… although perhaps we do have God to help us here.

Carr ends his statement with another claim from the mysterians. They tell us that “some of nature’s mysteries may forever lie beyond our comprehension”. This ties in with the first claim because only an omniscient intellect (or being) could comprehend literally all of “nature’s mysteries”.

It can be supposed, however, that if human beings were to survive for infinite years, then omniscience could (or would) be possible. It would be especially possible if human beings worked in conjunction with artificial intelligence or if they actually fused with AI. [See here.] Yet there’s still something odd about the notion of comprehending all of nature’s mysteries. That’s in the simple conceptual or quantificational sense of understanding what the “all” in “all nature’s mysteries” actually means.

Gödel Stuff?

Nicholas Carr also says that mysterians

“argue that the human mind may be incapable of understanding itself, that we’ll never understand how consciousness works”.

If Carr’s take on mysterianism is correct, then this passage has a Gödelian flavour to it. In very loose(!) Gödelian terms, a system cannot fully understand itself. Or, more correctly, a system will always leave something out when it accounts for itself. Of course, Kurt Gödel himself was only referring to mathematical and logical systems. Yet Gödelian incompleteness and unprovability have been applied across the board.

So is the human mind a system in the same sense in which a logical or mathematical system is a… system?

Moreover, Carr’s words

“the human mind may be incapable of understanding itself, that we’ll never understand how consciousness works”

may well include a non sequitur.

Say that the human mind can’t fully understand itself — what has that to do with consciousness? Sure, human minds are generally conscious, yet a mind-as-a-system doesn’t seem to be intimately connected to consciousness. Consciousness seems like a non-Gödelian problem. A problem, sure, but not a Gödelian problem. Indeed, isn’t consciousness the (not necessarily epiphenomenal) cream on the top of a system — including that of a human mind?

Mysterianism About All Nature

Carr makes the interesting point that if mysterians are right about human minds (as well as about consciousness), then why not apply their logic to “the workings of nature in general”? In fact, Carr shows us that one mysterian, Colin McGinn, has applied it to nature in general.

Carr quotes McGinn stating the following: “‘It may be that nothing in nature is fully intelligible to us.’”

A first reaction to that statement is to ask this question:

What is it for something in nature to be “fully intelligible to us”?

Does this tie in to the previous comments about omniscience? That is, if something in nature were to be fully intelligible to us, then we’d need to be omniscient… We aren’t omniscient. Therefore things in nature aren’t fully intelligible to us.

Evolution Anyone?

When Carr brings up evolution, all he (or a mysterian) really does is add extra dressing to a position which virtually everyone accepts anyway. So let’s quote Carr putting Stephen Pinker’s position on this. It goes as follows:

“If all the minds that evolution has produced have bounded comprehension, then it’s only logical that our own minds, also products of evolution, would have limits as well.”

Carr then quotes Pinker himself on this lack of evolutionary omniscience:

“‘The brain is a product of evolution, and just as animal brains have their limitations, we have ours.’”

We’ve already established that human minds have limits. Is that entirely due to evolution? Probably not, as was hopefully shown earlier. To state the obvious: evolution (or survival) doesn’t require omniscient minds. Indeed, psychologists may tell us that any being that had an omniscient mind may well be overburdened with information in those situations which required immediate action. That said, an omniscient mind would already know that it would be overburdened with information in a situation which required immediate action… So who knows?

Carr then adds his own take on Pinker’s words:

“To assume there are no limits to human understanding is to believe in a level of human exceptionalism that seems miraculous, if not mystical.”

This is both right and wrong. As already stated more than once, virtually no one argues for human omniscience. (Sure, perhaps they do so implicitly or tacitly.) However, I do believe in (with important qualifications) “human exceptionalism”. That’s because I also believe in ant exceptionalism, cat exceptionalism, whale exceptionalism, etc. In other words, all animals are exceptional in various ways.

(Famously, ants can lift or move huge weights. Bacteria can live in freezing temperatures. Camels fair very well in deserts. Cockroaches have a lineage which date back hundreds of millions of years. (This suggest that cockroaches must be exceptional in at least some ways.))

So what about human beings?

Aren’t the brains and minds of human beings exceptional in various and many ways? And doesn’t this particular exceptionality (possibly) lead to “human understanding” not being subject to the same limits Pinker puts on other “animal brains”?

Evolution or not, most other animal brains aren’t as big as human brains. And neither are they used for so many things which go beyond survival, getting food, sex and reproduction. Of course, none of this means that human brains are omniscient, or even that endless evolution will lead to human omniscience. However, perhaps it does show readers that Pinker’s focus on evolution and other animal brains may not be as fool proof as he imagines.

Mysterians Are Humble?

Carr finishes off by telling us how humble and modest mysterians are… Well, he finishes off by saying that “[m]ysterianism teaches us humility”. He adds:

“If the mysterians are right, science’s ultimate achievement may be to reveal to us its own limits.”

Mysterianism is hard to divorce from the philosophers who’ve formulated it. And its’s hard to detect much humility when it comes to mysterians. Or, at the very least, it’s hard to detect any more humility from them when compared to philosophers and scientists who advance other doctrines.

Indeed, there is some Socratic arrogance and phoniness here. Just as Socrates claimed that he “knew that he knew nothing", and was proud of the fact that he was — perhaps? — the only one to recognise that he knew nothing, so mysterians telling us that human intellects aren’t unlimited leads to a certain arrogance about their own (rather obvious) claim. In other words, like Socrates’ “I know nothing”, today we have mysterians telling us that “we can’t know everything”.

Added to that is the fact that certain mysterians have an “agenda” that’s way beyond simply telling us that human beings aren’t omniscient. Thomas Nagel, for example, uses his mysterianism as a prelude to advance many other arguments about philosophy, mind, reason and so on. [See here.] Pinker and Chomsky may use their own mysterianism to highlight the fact that we must remember that “we are animals” — which is true! But the obvious situation is that the conclusions of mysterians are used by religious people to advance what they call “anti-materialism”. In particular, they argue that consciousness cannot be fully known because it’s “uniquely special”. Indeed, it’s uniquely special because “consciousness is God’s gift to us”.

No comments:

Post a Comment