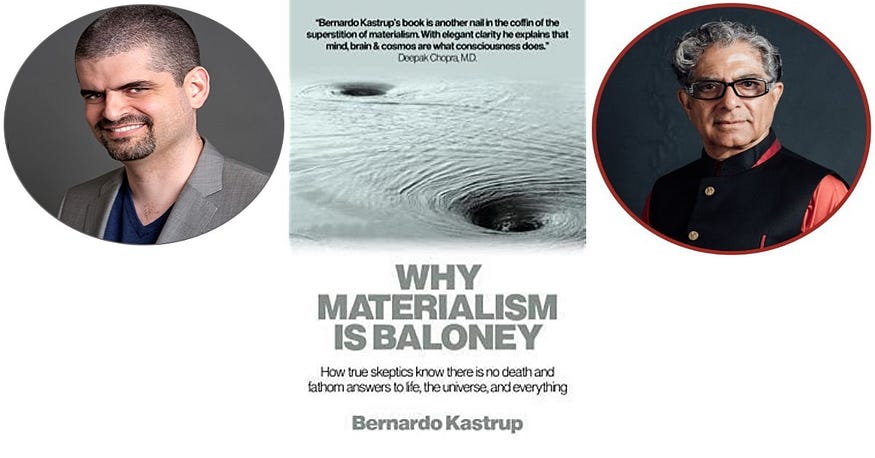

Bernardo Kastrup believes that “our culture [has] embraced materialism” — and he wants to change that.

The Dutch computer scientist and philosopher Bernardo Kastrup states his broad philosophical, sociological and — perhaps also — political take on materialism in the following words (as taken from his book Materialism is Baloney):

“A big part of the motivation for our culture’s current embrace of materialism is the observed regularities according to which reality seems to unfold.”

So clearly it isn’t just getting the metaphysics of “reality” right which concerns Kastrup. He’s also concerned with what “our culture embrace[s]” and the fact that (in his eyes) it embraces materialism. And that may at least partly explain Kastrup’s words “materialism is baloney”; as well as Deepak Chopra’s similarly intemperate remarks on materialism.

(It can be taken as given here that Kastrup means Western culture by “our culture” — that is, he means European, British and American culture.)

Yet it simply isn’t the case that our culture embraces materialism — and for many reasons.

Firstly, materialism is a philosophical position which most people never even consider, let alone uphold. Secondly, even if science itself is loosely based on a commitment to materialism, then that still doesn’t mean that our culture as a whole embraces materialism.

It was said a moment ago that materialism is a philosophical position. So it’s worth stating that scientists on the whole — like laypersons — don’t give materialism that much thought. (Many scientists simply “shut up and calculate”.) Indeed when some — perhaps even many — scientists do think about (philosophical) materialism, then they don’t actually (to use Kastrup’s word) embrace it at all.

Moreover, there are large chunks of our culture that certainly do not embrace materialism — from the very-large numbers of religious and “spiritual” people, to New Agers and the lovers of the arcane. Now add to that the many political activists and political theorists who do not embrace materialism. And, last but not least, take on board the many idealist, realist, etc. philosophers who’re strongly against what they describe as “materialism”.

So our culture — at least as a whole — clearly does not embrace philosophical materialism. That’s unless Kastrup simply means that everyone in our culture unconsciously embraces materialism by osmosis or that most folk just catch it in the air. (This would be Kastrup’s version of the notion of “false consciousness”.)

In any case, the fact that Kastrup and other idealists believe that our culture does embrace materialism may well also explain why they (rhetorically) claim that the commitment to (philosophical) materialism is based on “faith” or even that materialism is a “religion”.

So now let’s take Deepak Chopra’s own often poetic, very vague and rhetorical remarks on materialism..

Deepak Chopra’s Rhetoric

The following words show Deepak Chopra using playground techniques when he talks about the “superstition of materialism”.

In a commentary on Barnardo Kastrup’s Why Materialism is Baloney, Chopra writes:

“Bernardo Kastrup’s book is another nail in the coffin of the superstition of materialism. With elegant clarity he explains that mind, brain & cosmos are what consciousness does.”

This is an example of the tried-and-tested technique which many anti-materialists — along with those (it must be added) who reject evolution — employ on a regular basis.

To put it in its most simple form.

If a materialist, “evolutionist” or atheist accuses a religious person, spiritualist or New Ager of x, then the latter will accuse the former of being x too. Thus we have lots of religious, spiritual and New Age people who’ve accused materialists, evolutionists and/or atheists of having “faith” in materialism/evolution/atheism. Indeed they’ve also stated that “atheism [evolution or materialism] is a religion”.

This happens at a lot at infant and junior schools. That is, when a little kid accuses another little kid of being x, then that other little kid accuses the accuser of being x too.

Kastrup and Chopra’s bottom line is this. You accuse us of being x, but you don’t even realise that you’re x too.

It can be easily argued that very few religious/spiritual persons, New Agers, idealists, etc. genuinely do believe that materialism, atheism or evolution is a religion or that people believe in material/atheism/evolution purely on faith. Of course it must be admitted that there will be exceptions to this in that at least some materialists, atheists or evolutionists will use materialism, atheism or evolutionary theory as a literal substitute for a religion. Yet the comparisons between religion and people’s commitment to materialism, atheism and/or evolution are often so vague, tangential and rhetorical that, in most cases, I doubt that these claims are even believed by most of the anti-materialists who actually state them.

Still, to claim that materialists, atheists and/or evolutionists have faith in what they believe is extremely useful and it scores many points.

As for the rest of that rhetorical and over-the-top passage from Chopra above.

For a start, there will probably never be a final “nail in the coffin” of any philosophical theory. That’s primarily because philosophical theories aren’t scientific theories. (They aren’t logical or mathematical systems either.) So, in turn, it can willingly be admitted that there are no final nails in the coffin of (the “superstition”) idealism either. In philosophy, it simply doesn’t work that way.

Moreover, what is this “consciousness” which “does” such things as “mind, brain & cosmos”? And how, exactly, does it do mind, brain and cosmos? More directly, what do the words “mind, brain & cosmos are what consciousness does” actually mean?

All these questions will be tackled in the following essay.

*******************************

What is Matter?

Since we’re dealing with materialism, everything hinges on what the word “matter” (or “material”) actually means. So, at it’s most basic, you can’t go anywhere until you define “matter”.

It can be said that the British philosopher Mary Midgley (1919–2018) was right to argue that the word “matter” is — or has been — badly defined and elusive (see here). Yet even if that has been the case, then this fact hasn’t really got that much to do with the strong position against materialism advanced by many anti-materialists (in this case, idealists). That is, the idealists featured in this essay rarely refer to loose or vague definitions of the word “matter”. Instead, they simply state that materialists have got things wrong. And that’s primarily because (especially in Kastrup and Chopra’s case) idealists and anti-materialists believe that materialists don’t understand 20th-century physics (see later section).

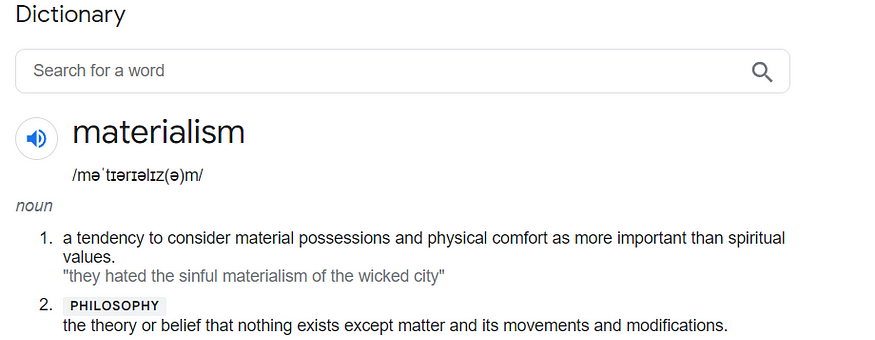

In any case, here’s one definition of “materialism” (if not “matter”):

Yet what is it, exactly, that moves or which is modified?

In that sense, the following definition isn’t of much help either:

“Materialism is a form of philosophical monism that holds that matter is the fundamental substance in nature, and that all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialism, mind and consciousness are by-products or epiphenomena of material processes (such as the biochemistry of the human brain and nervous system), without which they cannot exist [].”

Again: what is matter?

So until a particular materialist says exactly what he takes matter to be, then Kastrup, Chopra and other anti-materialists are bound to have a field day.

For most materialists, what matter is has come from what physics says it is.

That said, the position advanced above is (strictly speaking) only that of naturalist materialists (see naturalism) — i.e., those philosophers who look to physics and the sciences generally. (It is still possible to be a materialist and not be a naturalist.)

But, firstly, what about physicalism?

It can be argued that materialism actually is physicalism. Either that, or that the two are very closely related. In other words, both philosophical positions share the belief that all that exists is ultimately physical and natural (i.e., not supernatural).

(Some materialists make an exception for abstract objects and relations — see here. It can also be admitted that materialists face the same difficulties, on this issue at least, as nominalists.)

Yet it can also be argued that physicalism actually evolved from materialism in that the the latter was believed not to have taken on board such things as fields, forces, energy, spacetime, etc. (See later section.) However, it’s not clear that this was ever true about all — or even most — materialists. It would need a historian of philosophy to establish that point. In addition, it would also depend on which materialist is being discussed; and also, as ever, on how the words “matter”, “material” and “materialism” are being defined.

Over and above all that, there’s the simple fact that many philosophers still (in 2022) take the words “materialism” and “physicalism” as literal synonyms.

Anti-Materialists and 19th-Century Materialism

As already hinted at, Bernardo Kastrup and many other anti-materialists seem to conflate materialism itself with what many materialists believed in the 19th century and before — or at least up until (roughly) the 1920s. In other words, they have a view of materialism that might have been correct in the early 20th century. Yet even by the 1920s — if not before — this stereotype of materialism was no longer the case when it came to many materialists.

All this largely boils down to to anti-materialists and idealists claiming that materialists believe that all matter — and indeed everything else — is what they call “tangible stuff”. Indeed the frequent claim used to be — and sometimes still is — that materialists believe that everything is made up of “hard particles”.

Yet all that began to change with field physics in the 19th century — which all (naturalist) materialists almost immediately took on board. Why was that? It was largely because such materialists weren’t mindlessly committed to tangible stuff or to anything else like that— they were committed to the findings of physics and the other sciences. And physicists discovered fields (other than gravity) in the 19th century (see here).

In addition, when Einstein showed that matter and energy are interchangeable, many materialists immediately took that on board too. Thus, as an obvious consequence of that, many materialists also came to believe that energy — not matter — is (as it were) prima materia. Or at least they came to believe that matter is a form of energy.

Something similar occurred with the rise of quantum field theory.

Again, many materialists took quantum field theory on board. That is (as with Einstein’s equation of matter and energy), materialists came to see that fields — not energy — are prima materia; and therefore that energy is a property of such fields.

Again, the important point here is (even in the technical details of physics are wrong or misinterpreted) that although there was a (radical) shift in a part of physics, many materialists still took on board these new findings, commitments and theories of physics.

Werner Heisenberg and Logical Positivism

Idealists, anti-materialists and New Agers also often quote Werner Heisenberg (as well as other quantum physicists, such as David Bohm) to back up what they already believe anyway.

Heisenberg castigated 19th-century materialism and the materialism which existed immediately before the “quantum revolution” of the 1920s.

For example, Werner Heisenberg once wrote the following (which is often quoted):

“The ontology of materialism rested upon the illusion that the kind of existence, the direct ‘actuality’ of the world around us, can be extrapolated into the atomic range. This extrapolation, however, is impossible [] atoms are not things.”

So, in basic terms, with the rise of quantum physics in the 1920s, some physicists (not only Heisenberg) came to believe that the nature of matter (or the concept of matter) had been fundamentally altered. Others didn’t believe this.

As with so such in philosophy, then, Heisenberg’s position entirely depends on how his term “materialism” is defined and on what particular materialists actually believed at that time. It also has to be borne in mind that it’s an obvious fact that before quantum mechanics, materialists — both philosophers and scientists — wouldn’t have had a (as it were) quantum take on matter or on atoms — and that’s simply because no one did! (The physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach, for example, rejected the existence of atoms right up until his death in 1916 - see here. And Mach, incidentally, was also classed as a “subjective idealist” by many.) Indeed even quantum physicists didn’t agree — or fully comprehend — the philosophical (or ontological) implications of quantum mechanics in the 1920s and beyond.

So why single out materialists and what Heisenberg had to say?

In any case, there was never any necessary reason for materialists to believe that atoms are (to use Heisenberg’s word) “things”. That’s because materialists believed that atoms are things when most physicists believed — and still do — that atoms are things. Yet when many (quantum) physicists started to question that simple “classical picture”, then so too did many materialists. In other words, such materialists were taking their que from physics.

So now let’s bring this issue right up to date.

Today there’s no reason why a materialist should ever have a problem with, say, the Lambda-CDM model. In this model, old-style “matter” only makes up 5% of the density level of the universe. That is, certain — perhaps many — physicists now believe 95% of the universe is made up of dark matter and dark energy.

Again: the important point here is that (regardless of percentages and other details) many materialists go with the science (i.e., even if their metaphysics is not itself science).

In addition, many anti-materialists also tend to conflate (or fuse) materialism with logical positivism — and logical positivism is the victim of a very special disdain. (Ironically enough, Werner Heisenberg has often been classed as a positivist. Indeed he was positive toward positivism in the 1920s and 1930s; but he later changed his mind on this. See here.) Of course the fact is that physicalism also partly grew out of logical positivism (as did the strong critiques of logical positivism!) and that may at least partly explain this conflation (or fusion) carried out by anti-materialists.

In turns out, then, that the “dogmatic” stances of logical positivism are often being conflated (by anti-materialists and others) with materialism.

Kastrup vs. Materialism

Apart from conflating all materialism with 19th-century materialism (or even with ancient Greek atomism), Kastrup often either seems to caricature materialism or even — sometimes deliberately? — gets it wrong. Take this passage:

“It is materialism that states that the world we experience is entirely within our heads, stars and all. And it is idealism that states that it is our heads that are inside the world we experience.”

Materialism does not state that “world we experience is entirely within our heads, stars and all”! To state the obvious, materialists would argue that the experience itself (of the world) is in the head. Indeed why else would materialists (or anyone else) use the words “of the world” if this isn’t the position? So it’s ridiculous — for a materialist — to argue that the world itself (or “stars and all”) is literally “within our heads”. This is because that position would mean that something physical, causal, huge, complex, etc. is literally in the head..

Yet of course the materialist can happily admit that we require minds and consciousnesses to observe, think about, etc. the world — but the world itself still isn’t in the head…

That, of course, is the position of idealism.

So perhaps that’s precisely the point that Kastrup is attempting to make!

That is, via his crude caricature of materialism, Kastrup is attempting to argue that, in a strong sense, materialism is more idealist than… well, idealism!

To repeat: no materialist has ever denied that in order to know, observe, experience, etc. anything about the world, then we need to have minds or consciousnesses in order to do so. Indeed materialists would even happily admit that without consciousness we would know, experience, observe, etc. nothing of the world. So, yes, in a strong sense, “all we know are the contents of consciousness”…

But what follows from all that?

The obvious non-idealist point here is that in order to find out about the physical world, we don’t just focus on our own consciousnesses. Yet, according to idealism (or, at the least, according to subjective idealism), then this would be all we’d need to do. After all, to such idealists, there’s literally nothing but mind or the contents of consciousness.

Yet here again we come across a problem: some kinds of idealism (including Kastrup’s Cosmic Idealism) have it that the world (or universe) itself is consciousness (whatever that may mean). This means that we never get access to the physical world in any way. Or, if we do, then this would be an example of one consciousness (i.e., a human subject’s consciousness) gaining access to the universe that is consciousness — that is, in Kastrup’s parlance, to Cosmic Consciousness.

Added to that is Kastrup thesis that human consciousnesses and Cosmic Consciousness are one and the same thing anyway — even if (to use his word) human consciousnesses are “fragmented” from Cosmic Consciousness. So surely this must mean that when we know or observe the world, we’re essentially knowing or observing ourselves!

This position hints at pantheism. Either pantheism, or Kastrup’s Cosmic Idealism is some mystical or outrightly religious doctrine. Indeed Kastrup more or less says this himself in the following passage:

“This theory allows us to rest in knowing that we are part of something greater than ourselves, even if we are living in our own dissociative bubble.”

Part Two: Idealism/s

Kastrup’s Idealism and Other Idealisms

One problem is that of differentiating the many different kinds of idealism on offer.

Indeed, even in the following entry on idealism, the various descriptions of it seem to be very different and even sometimes seemingly self-contradictory. That’s not meant in the sense that different kinds of idealism contradict each other. What’s meant is that some of the given descriptions of the same kind of idealism seem to contain internal contradictions.

So take the following extended entry on “idealism”.

Firstly, and in direct relevance to Kastrup’s own personal brand of idealism, we have the following words:

“Epistemologically, idealism manifests as a skepticism about the possibility of knowing any mind-independent thing.”

Yet, to Kastrup, there is no “mind-independent thing” in the first place. That’s because he believes that all is consciousness. In Kastrup’s own words:

“ [W]hat idealism is saying is precisely that there is no stuff. There is only subjective perception.”

So one can accept (or simply take on board) the sceptical philosophical position which emphasises the many difficulties involved in the journey from the contents of the mind to everything — or anything — outside the mind. Yet all that is irrelevant when it comes to Kastrup’s own idealism. That’s because he believes that there are no mind-independent things (or at least things which aren’t consciousness) at all. So this isn’t the sceptical point that we can’t gain access to things outside the mind (or at least that we can’t know anything about the “external world”) — it’s that such (physical) things don’t exist (in any shape or form) in the first place!

The entry continues:

“In contrast to materialism, idealism asserts the primacy of consciousness as the origin and prerequisite of material phenomena. In According to this view, consciousness exists before and is the pre-condition of material existence.”

Again, according to Kastrup’s own idealism: the word “primary” is unsuitable and inaccurate here simply because — to Kastrup — consciousness is literally everything. Thus if consciousness is everything, then it can’t be primary when it comes to “material phenomena”. That’s simply because there are no material phenomena at all in Kastrup’s idealism. Thus consciousness can’t be primary, secondary or have any status in regards to material phenomena because the latter don’t even exist in the first place.

The same reasoning applies to the words “consciousness exists before and is the pre-condition of material existence”. There is no material existence in Kastrup’s brand of idealism. Thus consciousness can’t be a “pre-condition” for that which doesn’t exist in the first place.

The definition (or entry) continues:

“Consciousness creates and determines the material and not vice versa.”

Here again: if consciousness is everything (or if everything is consciousness), then there’s no “material” to “create and determine[]” in the first place. So Kastrup’s position, surely, is one of consciousness creating other “things” which are themselves consciousness. And Kastrup — on this reading at least — accepts this scenario.

The other problem here is with the word “creates” (as in “[c]onsciousness creates and determines the material and not vice versa”). If consciousness is everything, then why the need to create “the material” in the first place?…

Of course Kastrup believes that what we take to be material is, in fact, consciousness anyway. Thus (as stated a moment ago) consciousness must create other cases of consciousness.

So are we going around in (idealist) circles here?

Yet surely we can still ask (even if we provisionally accept the logic of idealism) this question: If consciousness creates matter (which, remember, is also consciousness), then why did consciousness create (what we take to be) matter in the first place? Why did consciousness create matter and not something else? Indeed why isn’t there a world without — what we take to be — matter?

Here again Kastrup again accepts matter — even if it’s deemed to be secondary — when he states the following words:

“Materialism assumes that mind arose in particular organizations of matter at some point in time. Under idealism, however, it was matter that arose in mind as a particular modality of experience.”

And elsewhere Kastrup writes:

“[T]hat all reality unfolds in mind does not deny that reality — as empirically observed — unfolds according to certain stable patterns and regularities that we’ve come to call the ‘laws of nature.’”

Yet if the mind is the only thing, then why any “laws of nature”, “stable patterns and regularities”, etc. at all?…

Is there where God (or something mystical or transcendent) enters the equation — as with Bishop Berkeley (1685–1753), who argued that God kept our “ideas” or experiences in order (see here)?

To repeat: if matter “arose in mind”, then why did it do so in the first place? Why did mind give birth to matter at all? If mind (or consciousness) is all there is, then why the need for this “particular modality of experience” rather than for something else or for nothing at all? Indeed if one stresses the primacy of mind (as well as the fact that matter “arose in mind”), then it’s hard to work out what work matter is actually doing.

And what does it mean to state that “matter [] arose in mind as a particular modality of experience”? If we forget the questions about why matter should arise in the first place, we still need to know what this process is and what Kastrup’s claim actually amounts to.

Finally, the entry tackles the many different kinds of idealism in the following passage:

“Idealism theories are mainly divided into two groups. Subjective idealism takes as its starting point the given fact of human consciousness seeing the existing world as a combination of sensation. Objective idealism posits the existence of an objective consciousness which exists before and, in some sense, independently of human ones.”

It can be argued that Kastrup’s idealism is some kind of fusion of subjective idealism and objective idealism. (See also absolute idealism, which is related to objective idealism.) Alternatively, his idealism may well be an original alternative to both these types.

At first glance, however, Kastrup’s own brand of idealism does seem to square very well with objective idealism. After all, Kastrup also believes that there’s

“an objective consciousness which exists before and, in some sense, independently of human ones”.

Moreover, in Kastrup’s book, aren’t “human” consciousnesses simply parts of the (capitalised) Cosmic Consciousness?

Here’s Kastrup again (in Scientific American) on this:

“The idea is to extend consciousness to the entire fabric of spacetime…. This view — called ‘cosmopsychism’ in modern philosophy, although our preferred formulation of it boils down to what has classically been called ‘idealism”’— is that there is only one, universal, consciousness. The physical universe as a whole is the extrinsic appearance of universal inner life, just as a living brain and body are the extrinsic appearance of a person’s inner life.”

Indeed even if human consciousnesses are (to use Kastrup’s word) “disassociated” from Cosmic Consciousness, then they’re still disassociated from Cosmic Consciousness. (Kastrup argues that, on a spiritual level, the trick is to re-associate with Cosmic Consciousness.)

The possible fusion of objective and subjective idealism was mentioned a moment ago.

Kastrup may still accept “the given fact of human consciousness seeing the existing world as a combination of sensation” (as in subjective idealism). That is, a disassociated consciousness (i.e., of a human being) is indeed mainly — or even only — aware of his own sensations. Yet that’s the case even though, Kastrup believes, a human subject of consciousness can still gain access to (or re-associate with) Cosmic Consciousness. Thus subjective consciousness is — or can be — a means to reconnect (or re-associate) with Cosmic Consciousness.

As Kastrup himself freely admits, all this stuff about Cosmic Consciousness is perfectly in tune with various religious and/or spiritual traditions.

Note: Professor Donald Hoffman’s Cosmic Idealism

There are many connections and similarities between Bernardo Kastrup’s idealism and Donald Hoffman’s idealism. In some cases, their positions are virtually identical.

Hoffman’s own conscious realism (like Kastrup’s idealism ) can be seen as being a new-fangled take on idealism — i.e., it’s idealism with self-consciously added mathematical and scientific knobs on.

So part of my stance against Hoffman’s and Kastrup’s idealisms is best summed up by (of all people) Slavoj Žižek (1949- ). The Slovenian philosopher warns us about the

“New Age obscurantists appropriations of today’s ‘hard’ sciences which, in order to legitimize their position, invoke the authority of science itself”.

It can now be added that we all know about the Flat Earthers, Creationists, etc. whose books are replete with mathematical equations, technical terms from physics, graphs, stats, an infinity of references/footnotes, etc. In other words, we need to be careful when people drop scientific technical terms, etc. into their writings.

Indeed just like Kastrup, from what Hoffman writes himself (as well as from the many comments he’s made on spirituality, mysticism and religion and the time he has given to people like Deepak Chopra), it seems that there are many non-scientific motivations behind Hoffman’s conscious realism (or idealism). This, of course, isn’t to claim that Hoffman doesn’t provide any arguments and scientific data for his speculative philosophy.

The bottom line is that there’s much that Hoffman and Kastrup state which seems to be tailor-made for those who have religious, spiritual and mystical (i.e., non-scientific and non-philosophical) views of what “reality” truly is.

For example, take these words from Hoffman:

“According to conscious realism, you are not just one conscious agent, but a complex heterarchy of interacting conscious agents, which can be called your instantiation [].”

Clearly Hoffman is advancing some kind of “holistic” (for want of more suitable words) interconnectedness vibe here.

Having said that, the fact that New Agers, etc. are now gobbling up Hoffman’s and Kastrup’s words and theories doesn’t automatically make them false or unscientific. This would be an example of relying on guilt by association. However, it does give people very-good grounds for varying degrees of suspicion or scepticism.

It can be said that much of what Hoffman and Kastrup say is also closely connected to “mysticism”. That’s not my own word, Hoffman himself uses it a few times. (He usually does so in interviews and seminars, rather than in his academic papers.) Despite that, Hoffman — if not Kastrup — does (at least at times) distance himself from such things. He does so primary by saying such things as his position

“give[s] a mathematically precise theory of conscious experiences, conscious agents, and their dynamics, and then make empirically testable predictions”.

So Hoffman’s (if not Kastrup’s) rejoinder may be that he’s certainly not doing religion, spiritualism or mysticism because of the scientific nature of his theories. Yet it can still be argued that the very least Hoffman should say is that he’s not only doing religion, spiritualism or mysticism.

Now let’s ignore whether or not there are genuinely scientific aspects to conscious realism and put forward the fact that Hoffman’s and Kastrup’s uses of — and references to — science are employed to advance positions (at least in part) which already existed long before — and independently of — all science. (Hoffman concedes as much here.) That, of course, doesn’t mean that the two independent magisteria of science and religion/spirituality/mysticism can never be squared. Indeed I believe that Hoffman and Kastrup are attempting to square them.

The term “magisteria” has just been used.

This is Stephen Jay Gould’s term and it’s been quoted by Hoffman himself. However, it can be argued that since Hoffman is attempting to literally fuse (or unite) these two magisteria (i.e., science and religion), then that must surely go against what Gould himself had in mind — i.e., he stressed the mutual independence of science and religion.

(For further detail on Hoffman and religion: see this video in which Hoffman presents himself as offering a midway position between theism/deism and atheism. Later in the same video, Hoffman concedes that he’s “giving religious people something that will be positive to them”. And here Hoffman argues that all the scientific cases against the existence of God fail. Finally, in this interview Hoffman says that the relationship between science and spirituality is “very deep” which was true, at one point. More specifically, Hoffman states that “many of the spiritual traditions have been telling us for centuries, even millennia, that spacetime is not fundamental but there’s a deeper reality outside of spacetime”. Of course Hoffman will be keen to stress than none of these positions make him either a religious person or a theist/deist. So does Hoffman have his cake and eat it too?)

In terms of (technical) scientific and philosophical detail.

Just like Kastrup, Hoffman puts the consciousness-first position when it comes to human brains (see my next essay) when he says that

“[b]rains do not create consciousness; consciousness creates brains as dramatically simplified icons for a realm far more complex, a realm of interacting conscious agents”.

As for Kastrup’s Cosmic Consciousness, here Hoffman himself states that consciousness

“is not a latecomer in the evolutionary history of the universe, arising from complex interactions of unconscious matter and fields”.

“Consciousness is first; matter and fields depend on it for their very existence.”

To sum up.

Steve Tolley captures the main problem with Hoffman’s conscious realism. That problem is Hoffman’s seemingly quick and easy move from scientific data (i.e., from cognitive science, evolutionary theory and physics) to (pure) philosophical speculation.

So take this expression of Hoffman’s long jump. Tolley writes:

“Hoffman is not doing science, he constructs a solipsistic metaphysics based on illogically elevating the simple fact that our experience of something is filtered through our perceptual apparatus to the metaphysical axiom that this entails there are no public objects.”

In other words, from the fact that your experience of a (to use Hoffman’s example) table isn’t identical to my experience of that very same table, Hoffman derives the metaphysical conclusion that the table only exists in one person’s head or in many persons’ heads. Yet Hoffman fails to realise that metaphysical realists — and even naïve realists — have never claimed that all experiences of the same table (at the same time) need to be identical. All these realisms simply argue that there’s a table which is beyond all acts of consciousness and experience. However, unlike anti-realists, metaphysical realists believe that we can get that table as it is in itself. Hoffman, on the other hand, believes that the table (as simply an “icon”) is entirely in our consciousnesses.

*) To follow: ‘Bernardo Kastrup on the Images of the Brain, Not the Brain’s Images’.