Kurt Gödel once wrote that

“[o]ur logical intuitions (i.e., intuitions concerning such notions as: truth, concept, being, class, etc.) are self-contradictory”.

And Gödel didn’t have any problems at all with self-reference either. He also wrote the following:

“Contrary to appearances, such a proposition involves no faulty circularity, for it only asserts that a certain well-defined formula … is unprovable. Only subsequently (and so to speak by chance) does it turn out that this formula is precisely the one by which the proposition itself was expressed.”

In the following it will be argued that it’s not simply a question of what Gödel called “faulty circularity”. Perhaps it’s also about whether anything at all can be affixed to (or said of ) such sentences as “This statement” or “This statement is not provable”. More specifically, if the words (or clause!) “This statement” are semantically and metaphysically empty, then perhaps we don’t even need to worry about Gödel’s faulty circularity.

For example, the problem is that the sentence

This statement is not provable.

is impeccable in terms of logic alone. (Or so the usual — often implicit — position seems to be.) Thus semantics and certainly metaphysics are irrelevant here. That is, the words “This statement” make a perfectly acceptable “word string” in terms of logic. That means that there’s no problem at all with affixing the suffix/predicate “is not provable” to it. So here this means that logic is completely independent of semantics and/or metaphysics — and that’s despite the use of language-language expression! But if the sentence “This statement is not provable” (or “All Cretans are liars”, for that matter) is used only to display purely “logical facts” (i.e, facts about paradox or self-contradiction), then why use natural-language expressions in the first place?

It may be this logical focus (i.e., the divorce from natural-language expressions) which help create the paradoxes and self-contradictions in the first place.

Despite that logical independence, Gödel also moved beyond mathematics, logic and even metamathematics (into philosophy) when he stated that

“our logical intuitions (i.e., intuitions concerning such notions as: truth, concept, being, class, etc.) are self-contradictory”.

All this is vaguely equivalent to Bertrand Russell’s attempt (in the early 20th century) to find what he called the “logical form” (a term which Russell first used in 1914) of faulty natural-language expressions (or, more importantly, statements). Thus logicians and philosophers (at that time at least) were actually finding the logical form of natural-language — and also philosophical - expressions such as “The King of France is bald”. But those “hidden” logical forms were simply the end product of a long process of a logical — and indeed philosophical — scraping away of everything that is contextual, semantic and metaphysical.

Let’s put all that another way.

Think now in terms of Gödel numbers.

We can assign a number to the words “This statement”. Then we can assign another number to the words (or predicate) “is not provable”. And once we have those numbers (or those arithmetical particles) assigned, then we can play all sorts of games with them.

However, the sentence “This statement is not provable” is a natural-language expression. That’s the case no matter what logical games we can play with it. And if we’re using a natural-language expression, then we must abide by the realities (or facts) of natural language — even if those realities (or facts) are far from being determinate, rule-bound or immune to philosophical dispute.

Thus we can now turn the sentence “This statement is not true” into the purely symbolic

¬p

Yet even here we’d need to clarify what the symbols p and ¬ mean in a natural language. So, in this case at least, can such symbols really be (as it’s often put about logical symbols) “drained of all meaning”?

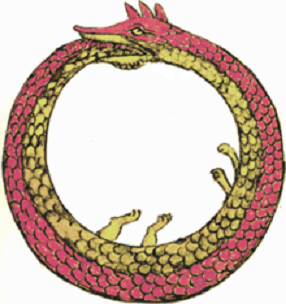

Self-Reference

Gödel offered us his own self-referential formula. Or, more accurately and relevantly to this piece, we have this natural-language sentence:

A certain number, x, is not provable.

(The statement above doesn’t stop being a natural-language expression simply because it includes the variable x and the word “provable”.)

In some cases at least, Gödel showed us that the (Gödel) number x within a formula will happen to represent that very formula itself. Gödel himself said that “this formula is precisely the one by which the proposition itself was expressed”.

So if the symbol (or number) x represents the entire formula, then don’t we really have the following? -

A certain number, x (x = A certain number x, is not provable), is not provable.

In other words, what’s in the parenthesis above is actually a part of the whole sentence — a necessary part of the whole sentence. To put that another way. The entire sentence has itself embedded within itself (as the symbol/number x) like a Russian doll within a Russian doll. Except, of course, one Russian doll must be smaller than the other; whereas x must be exactly the same as the sentence in which it is embedded. Yet surely this creates an infinite regress. That is, if

i) The x in the statement “A certain number, x, is not provable”

itself refers to the statement “A certain number, x, is not provable”, then don’t we have this? -

ii) A certain number, x… (x = A certain number, x… ((x = A certain number, x… (((x = A certain number, x… ((((x = A certain number, x… ((((( x = A certain number, x… ((((((… ad infinitum…)))))) is not provable.

Or it is simply this?

A certain number, x (x = a certain number), is not provable.

Now take this simpler statement:

This statement is not provable.

Again, is Gödel’s position about the whole formula (i.e., “This statement is not provable”) or is about the embedded sentence/clause (i.e., “This statement”)? It may seem that the whole sentence/formula is about itself. Therefore Gödel’s position applies to the whole of the sentence “This statement is not provable”, not simply to the embedded clause “This statement”.

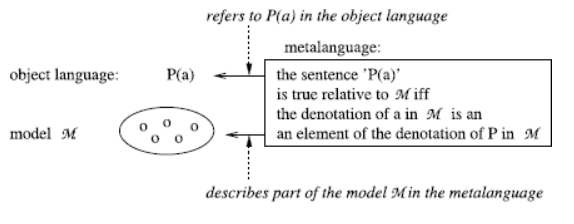

The Metalanguage

On a similar theme, is the whole statement

i) This statement is false.

part of a metalanguage simply because the words/predicate “is false” is affixed to the words “This statement”? (One can ask here why “This statement” is a statement at all — see the section ‘Empty Paradoxes’ later.) Or is the longer sentence

ii) The statement “This statement is false” is false/true.

part of a metalanguage? Thus if everything is within within the same sentence (as in example i)), then how can it really be an example of a metalanguage (or a case of “language about language”)?

On the other hand, perhaps only the suffix/predicate “is false” is metalinguistic.

Take Alfred Tarski’s object-language/meta-language distinction. In this case, the meta-language is completely separated from the object-language. Yet in i) above we seemingly have both the object-language and the meta-language within the very same sentence (i.e., or sometimes within the same quotation marks). That certainly breaks Tarski’s own golden rule.

Of course that may simply be a question of grammatical layout. That is, perhaps

i) This statement is false.

is simply shorthand for the following:

ia) The statement “This statement is false” is true/false.

In many other self-referential or Gödelian statements the predicate/suffix “is provable” often occurs. That suffix/predicate hints at the possibility that all the proofs of mathematical systems — and the statements within them — must come from metalanguages. That is, they must exist outside the systems.

However, it’s not that proof exists outside the system.

Statements within a system have be proved or are provable. So it’s the suffix/predicate “… is provable” that’s outside the system, not the proofs themselves. And that may simply be because the words “is provable” are from a natural language. That is, they’re not themselves mathematical or logical symbols. That said, all logical and mathematical symbols have a natural-language expression. So a further two questions can now be asked:

1) Do natural-language expressions of mathematical/logical symbols and symbolic statements/equations truly capture the whole logical/mathematical import of those symbols and statements/equations?

2) Do these natural-language expressions add something (problematic) to those logical/mathematical symbols and statements/equations?

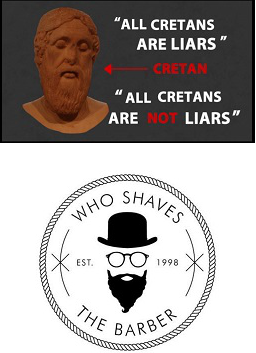

The Cretan Liar and the Barber Paradox

The Cretan liar paradox also provides us with a perfect example of self-reference.

In 1869 Thomas Fowler expressed the Cretan liar paradox as follows:

“Epimenides the Cretan says that ‘All the Cretans are liars’, but Epimenides is himself a Cretan; therefore he is himself a liar.”The upshot is this.

Epimenides stated: “All Cretans are liars”. He was a Cretan. Therefore he was a liar. That means that his statement “All Cretans are liars” must be a lie (or false).

Put differently. All the above means that if what Epimenides says is true (i.e., that all Cretans lie), then it must be false because he’s a Cretan and all Cretans are liars. That is, if a Cretan (as one of the set Cretan Liars) says that “All Cretans are liars”, then that statement must be false.

Furthermore, if the statement “All Cretans are liars” is itself a lie (i.e., false), then that must mean that at least some Cretans must tell the truth. So is this particular Cretan (i.e., Epimenides) one of those Cretans who tells the truth? After all, the statement “All Cretans are liars” doesn’t need to translate into “No Cretans are liars” simply because Epimenides himself may be an exception. It may simply have been that some Cretans are liars. So was the Cretan who made this statement himself a liar or a truth-teller? If he’s a truth-teller, then it may be the case that all Cretans are liars… But he is a Cretan himself!

The Cretan liar paradox also highlights a problem which runs through this piece. That problem is one of the application of logic to natural-language statements or expressions. Or, inversely, the problem occurs when the logical form of natural-language statements/expression is (as it it used to be put) “discovered”. (This was mentioned in the introduction.) If these things are done, then they often throw up paradoxes or self-contradictions.

Basically, one possibility is that the statement

“All Cretans are liars.”

should really be

“Except for myself, all Cretans are liars.”

That is, the above is a more natural and less problematic natural-language expression of the words “All Cretans are liars”.

However, the universal quantifier “all” ( or ∀ in logic) is somewhat negated by the proceeding clause “Except for myself”. This also has the consequence that it is no longer paradoxical or self-contradictory.

However, the universal quantifier “all” ( or ∀ in logic) is somewhat negated by the proceeding clause “Except for myself”. This also has the consequence that it is no longer paradoxical or self-contradictory.

This all hinges on the quantifier “all” and the problems (or difficulties) self-reference throw up. In logic, it’s often agreed that quantifiers nearly always have a restricted range (or domain) which is determined by specific contexts. So does the word “all” in “All Cretans are liars” have a restricted range? Is the speaker of the words “All Cretans are liars” that very restriction (or exception) himself? If we take the word “all” literally, then he can’t be. However, if we take the word “all” contextually or as a quantifier with a restricted range, then he may well be that very exception. After all, in natural-language terms (therefore in terms of context), many people would be happy to accept that when a person says that “All people are evil” (or says that “All people are nice”), then he may well be exempting himself from that statement. Indeed if someone were to say (out loud) that “All people always remain silent”, then (by definition) he must be an exception to his own universal statement.

So what about the Barber paradox?

This paradox isn’t about a single self-referential statement. That is, it can only be established through a chain of arguments. It is self-referential, however, in that it deals with the question of whether the barber does or doesn’t shave himself. Nonetheless, it’s not about a self-referential statement (or sentence) — as in the Liar paradox.

Of course the Barber paradox can be (partly) summed up in a single sentence. For example:

“I shave everyone who doesn’t shave themselves.”

Despite that, the paradox is still not a self-referential sentence like “I am lying at this very moment”. It’s about a self-referential situation (as it were); though, unlike the Lair paradox, it isn’t about a single sentence referring to itself (or a person referring to what he himself is currently saying). Thus the Barber paradox is about a possible (or impossible) state of affairs; not about a self-referential statement.

Empty Paradoxes and Semantic Content

Many logicians have argued that (semantic) content isn’t required when it comes to self-referential statements like “This statement is false”. Yet specifically in reference to the Liar paradox, one logician wrote:

“[The Liar paradox] led to the collapse of logicism and indirectly to Gödel’s incompleteness results (i.e., that in a formal system like Zermelo-Frankel set theory you can derive (G(F) = ‘This sentence cannot be proved in F’.)”

Gödel’s “This sentence cannot be proved in F” isn’t like the Liar paradox — at least it’s not precisely the same.

Put it this way. The following

Statement S in system A is true though it can’t be proven to be true in A.

isn’t like a single sentence which refers to itself. The above states that a statement (or mathematical truth) within a system is true even though it can’t be proven within that system. This means that Gödel’s “S in x” is true — just not proven to be true within the system to which it belongs. The problem with the Liar paradox, on the other hand, is that it can’t be established if it’s true or false (or if it’s both) at all.

Now take the following:

(A) The sentence A is false.

Isn’t it the case that statement A has no semantic content? Perhaps it’s not a genuine statement (or proposition) at all. Nonetheless, since many logicians and philosophers don’t take this view, let’s take it as they take it — as being a genuine (if paradoxical) statement.

The first thing to say is that it’s self-referential. Again, just like the Liar paradox, it’s about itself. (Here’s a list of other self-referential paradoxes.)

We have the sentence “(A) The sentence A is false”, which includes the symbol A. And A stands for the sentence it is in or the words which surround it. That means that a symbol (i.e. A) within a sentence refers to the sentence which it is in. Thus we have this again:

The sentence A… (A = The sentence A… ((A = The Sentence A… (((A = The sentence A… ((((A = The sentence A… ((((( A = The sentence A… ((((((… ad infinitum…)))))) is false.

Now what, precisely, is true or false? Sentence A is true or false. What does sentence A say about itself? It says that it’s “false” — and that’s it. It doesn’t say its subject-term (or phrase) is false: it says that the whole sentence is false.

So if we take out the A from the original statement “The sentence A is false”, then what do we have left? This:

The sentence… is false.

Since A only refers to the sentence itself, then why can’t we take A out? And if we do that, then what are we left with? It’s already been said that “The sentence A is false” is without content: so it’s even more the case that “The sentence… is false” is without content.

This can be boiled down even more.

We’ve already removed the A: now we can also remove the words “is false”. After all, the predicate “is false” must be applicable to something else. So what is the “is false” (in “The sentence A”) applicable to? That’s right, the “is false” suffix/predicate/clause is applicable to “The sentence”! So the two words “The sentence” are meant to be either false. Yet how can the two words “The sentence” be either true or false when they say precisely nothing?

To recap. It’s being argued here that the statement

(A) The sentence A is false.

is a pseudo-statement with no semantic content. Another way in which the same thing can more or less be said is to say that it’s malignly self-referential. Or, more correctly, that truth can’t be applied self-referentially (as Tarski argued) — especially when the statement has no content in the first place. Indeed it’s self-referential precisely because it has no content.

So what about a sentence which has a sentence embedded within itself which does have content? Take this example from Tarski:

(S) The sentence “Snow is white” is true iff p.

Now that’s not really a single sentence (or statement) at all. It is in fact two sentences. We have the embedded sentence 'Snow is white' as well whole sentence “This sentence ‘Snow is white’ is true iff p”. Thus it isn’t self-referential. The meta-language “The sentence ‘Snow is white’ is true iff p” is being applied to the object-language’s 'Snow is white'. The statement 'Snow is white' clearly has content and the whole sentence “The sentence ‘Snow is white’ is true iff p” isn’t self-referential either because there’s both a meta-sentence and an object-sentence.

Despite all that, logicians defend the sentence “The sentence A is false” for two main reasons:

i) The words “is false” are an acceptable English predicate.

ii) The whole sentence is grammatically “unassailable”.

Is it grammatically unassailable? I don’t think it’s either logically or philosophically unassailable (or acceptable). And now the grammar can be rejected too.

Again, the argument is that we can grammatically assert the sentence “The statement A” and grammatically apply the words “is false” to it. But that depends on what’s meant by “we can grammatically assert the sentence”. Can we? Grammar, unlike logic, is largely about what is acceptable to say in order to make sense (or communicate) in certain contexts. Now “This sentence” (or “This sentence A is false”) isn’t grammatically acceptable for precisely the reasons given. (It’s roughly equivalent to saying “I walk down” or “This is” — and no teacher of English grammar would accept this locution without the speaker or writer also supplying some sentential or semantic context.)

So we can conclude by saying that this is why the philosophy of logic is over and above pure (or formal) logic.