All philosophical movements and positions can be criticised and taken apart… All of them have been. Yet logical positivism seems to have been the victim of particular disdain and sometimes even vitriol. Across the board, from religious critics to postmodernists, logical positivism has been extensively “critiqued” — far more so than many other movements and positions.

One often reads the word “positivist” used in a sneering manner [see here], whether by a leftwing sociologist, a right-wing Christian or a student of philosophy who’s picked up on the common tropes against logical positivism. As a example, Ernest Gellner, for one, once wrote:

“Marxist theoreticians nowadays tend to be anti-empiricist in the social sciences (they use a special term, ‘positivist’, to designate anyone using facts against Marxist theories), and in their eagerness to protect interpretations from mere fact (discounted as superficial) they have been entirely willing to enlist this Idealism under a new name.”

One wonders, then, what it is about logical positivism that’s provoked so much ire. Oddly enough, the faults with logical positivism which logical positivists themselves discovered (such as its internal contradictions, its simplified view of science and, of course, the many problems with the “verification principle”) are rarely the target of those harshest critics who have other concerns. Take this example:

“[D]ehumanizing the human — taking away everything that makes them human. Atomism, reductivism, and materialism don’t fully acknowledge the difference. They also don’t acknowledge: the mind, the consciousness (it’s the hard problem for a reason), or agency (or free will)… Meaning, purpose, and context can’t be captured by the physical.”

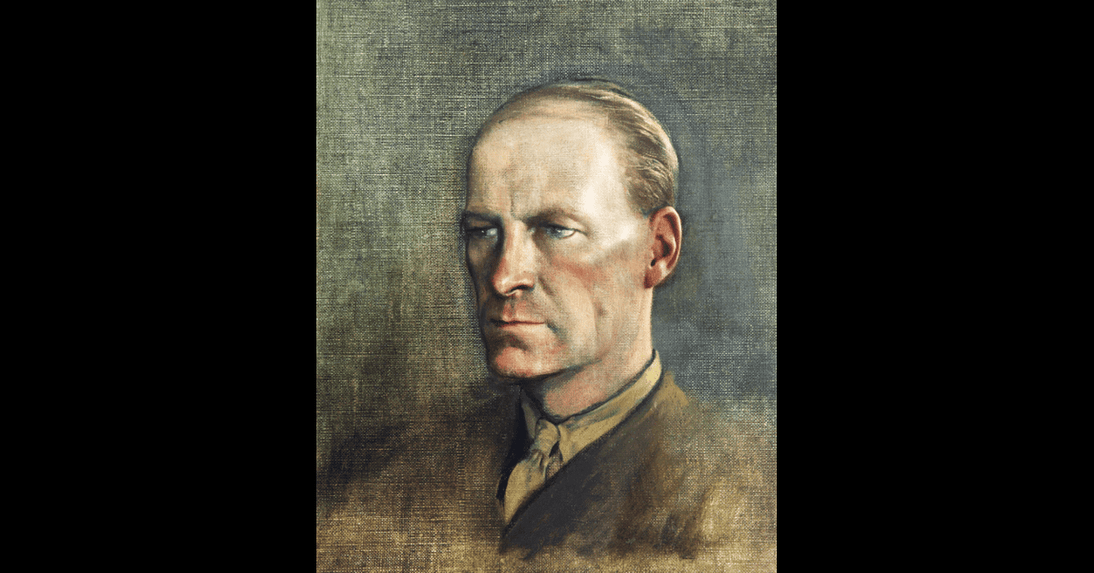

It was mentioned earlier that all philosophical movements and positions can be criticised. So, interestingly enough, one strong critic of logical positivism was Karl Popper [see here], and he has also been extensively criticised. Indeed, his particular criticisms of logical positivism have been taken apart. It’s also worth noting that the strongest criticisms of logical positivism came from logical positivists themselves, as well as from those who were initially inspired by — or connected to — the movement (e.g., W.V.O Quine).

Some History

Logical positivism (in its various forms) existed until the 1960s. In 1967, the philosopher John Passmore ostentatiously pronounced logical positivism “dead, or as dead as a philosophical movement ever becomes”. Dead or alive, Passmore, in his book A Hundred Years of Philosophy, still spent much time on logical positivism. This was his own homage to logical positivism’s importance and influence.

In detail, logical positivism became technically unsustainable. However, it’s influence continued. Indeed, one of its main critics, W.V.O. Quine, said that he’d retained the “spirit of positivism” despite the technical problems. The English philosopher A.J. Ayer, too, said that logical positivism was “true in spirit”.

Logical positivism was a very wide movement, despite the disdain and stereotypes of its many critics. Even its verification principle was interpreted in many ways. Logical positivism also had its “conservative right wing”, “a radical left wing”, and a “liberal wing”. (These fairly crude categorisations referred to both the philosophical and the political positions of the logical positivists.)

As many commentators argued at the time and long after, the main problem wasn’t that logical positivism was “scientistic” or that it suffered from “physics envy”: it was that, at least during one short period and according to its critics, many logical positivists attempted to become the masters of science, rather than its servants. Simply put, (some) logical positivists took on this role in order to tell scientists what they could and couldn’t say. Most (but not all) logical positivists denied this, of course. All that said, logical positivists (at least at one time) were indeed “reductionists” in that they argued that all the laws of the special sciences should be reduced to fundamental physics.

Logical Positivism vs Metaphysics

Logical positivism was largely a reaction against metaphysics. So, was that a reaction against speculative metaphysics, or literally all metaphysics? Of course, it’s often said that it’s virtually impossible to escape from metaphysics, whether in philosophy itself or in everyday life. Still, even sympathetic philosophers know that metaphysicians can often run riot. The problem is how to decide why that’s the case.

In any case, the logical positivist Rudolf Carnap, for one, did accept theoretical terms and believed that they refer to unobservables. (Empirical terms, on the other hand, were deemed to be responses to “direct observation”.) That said, it was still the case that Carnap tied such theoretical terms to observation terms via “correspondence rules”. Here again, reduction entered the picture in that theoretical terms and theoretical laws were to be reduced to Carnap’s protocol sentences, which were themselves grounded in observation.

The empiricism of logical positivism seems like an obvious antidote to metaphysics. After all, and in crude terms, if “direct experience” is the final and only arbiter of both meaning and truth, then surely metaphysics — or at least speculative metaphysics — is breaking all sorts of empiricist rules. What’s more, some metaphysicians have prided themselves on the fact that their metaphysics pays little — or no — attention to experience or the way the world presents itself to (fallible) human beings. Moreover, philosophers like Plato warned us that experience is — always? — misleading.

Plato has just been mentioned. However, note what Maurice Schlick wrote in 1929:

“Many assert that metaphysical and theologising thought is again on the increase today, not only in life but also in science. Is this a general phenomenon or merely a change restricted to certain circles? The assertion itself is easily confirmed if one looks at the topics of university courses and at the titles of philosophic publications.”

Logical positivism did (seem to) kill metaphysics… at least for a certain period, in certain places and in certain senses. But did logical positivism itself really escape from metaphysics? Quickly, take Carnap’s words quoted earlier. He stated that “the meaning of every statement of science must be statable by reduction to the given”. Is that statement itself grounded in experience? Can it be reduced to the given? Moreover, is the (in a manner of speaking) platonic form Science given to us through experience? Finally, the grand statement that “Philosophy is that activity through which the meaning of statements is revealed or determined” is actually normative in nature, not empirical. (There is some debate as to whether or not logical positivists themselves accepted the fact that most of their own pronouncements were normative and/or higher-order.)

Logical Empiricism

Logical positivism became logical empiricism, and it was empiricism that was at the heart of this movement. In addition, alongside a commitment to empiricism was a commitment to science (especially to physics). So perhaps the logical positivists did suffer from what later became known as “physics envy”.

But what is empiricism in the specific context of logical positivism?

Take the words found in the manifesto of the Vienna Circle, as written in 1928:

“In some circles the mode of thought grounded in experience and averse to speculation is stronger than ever, being strengthened precisely by the new opposition that has arisen.”

These words don’t tell us what empiricism is, or what the words “grounded in experience” mean. (Carnap once used the term “cross-sections of experience”.)

Let’s tackle experience and meaning together, as the logical positivists did.

It’s often said that logical positivists simply concerned themselves with “analysing sentences”, or, more specifically, analysing scientific statements. Maurice Schlick expresses this in detail:

“[P]hilosophy is that activity through which the meaning of statements is revealed or determined. By means of philosophy statements are explained, by means of science they are verified.”

Readers may note the use of the word “statements” rather than “sentences”. That word was used because, at one time at least, the logical positivists were only concerned with (as it’s put) fact-stating sentences, not with other sentential locutions. And it was the statements of philosophy and science which concerned the logical positivists. So, we’ll need to know what the words “revealed or determined” mean, as well as how science “verified” such statements.

It’s here where we get back to experience.

Fact-stating sentences were mentioned a moment ago. What is a factual statement (i.e., according to the logical positivists)? A factual statement must be meaningful (or “cognitively significant”). And how does a factual statement achieve this? It does so because (or if) it has been empirically verified — or if it could be empirically verified “in principle”. Another way of tackling the notion of empirical verification is to know what conditions would (or could) establish a statement’s truth. And the conditions which would establish its truth would be, in basic terms, observations. Indeed, from this way of looking at things arose the famous verification principle.

The positions above raise two issues, which were well-tackled in subsequent years: (1) Exactly how is a statement verified? (2) What is an observation?

The following is A.J. Ayer’s take on a sentence and its verification:

“We say that a sentence is factually significant to any given person, if, and only if, he knows how to verify the propositions which purport to express it.”

Taken in isolation, this sentence doesn’t really help us because Ayer didn’t tell his readers how a sentence is verified. Alternatively put, Ayer didn’t tell his readers what exactly it is that verifies a statement. According to Carnap and others, it is a reported observation which verifies a statement. Carnap himself called the sentences which reported observations “protocol statements”.

Here’s where the empiricism of logical positivism really kicks in.

Some philosophers believed that Carnap’s protocol sentences referred to “immediate sense-experiences”. So what are sense-experiences, and how are they circumscribed and delineated? What’s more, how do we move from such sense-experiences to statements about them (i.e., to protocol sentences)?

These aren’t easy questions to answer. And that’s precisely why the logical positivist Otto Neurath argued that protocol sentences must actually refer to physical objects, not to the sense-experiences which objects bring about. Yet isn’t it equally the case that physical objects also need to be circumscribed and delineated? And, if that’s the case, then one can see why Carnap once argued that sense-experiences are both more precise and more immediate than our access to — and cognisance of — physical objects. (These questions were well-tackled in the1930s and 1940s.)

Logical Positivism and Science

Readers may now be wondering what the precise — or technical — links between the empiricist positions of the logical positivists and science (or physics) were. The following passage is Otto Neurath on that subject:

“Since the meaning of every statement of science must be statable by reduction to the given, likewise the meaning of every concept, whatever branch of science it may belong to, must be statable by step-wise reduction to other concepts, down to the concepts of the lowest level which refer directly to the given.”

With its reference to “the given”, one could say that this passage has really dated. That said, there are still some philosophers who endorse some version or other of the given. [See work on what’s called “non-conceptual content”.]

So, in Neurath’s respect at least, what is the given? Well, it must be sense-experiences and observations.

The logical positivists particularly came on board the “scientific project” when they offered scientists(!) “the meaning of every concept [by] stat[ing] by step-wise reduction to other concepts, down to the concepts of the lowest level which refer directly to the given”. One can’t really imagine physicists doing any of this — at least not with their scientific hats on. In any case, one can see how vitally important the given was to the logical positivists at this time. That is, how important immediate experience was to them. (This position has been called “reductive phenomenalism”. Such a stance may, or may not, lead to idealism. So, do empiricists refuse to take their empiricism to its logical conclusion?)

It was said earlier that Neurath stressed physical objects rather than sense-experiences (or the given). Yet the passage above shows that at one time his position was otherwise. So, despite the position quoted above, some logical positivists moved from reductive phenomenalism to arguing that protocol sentences really referred to (everyday) physical objects. Thus, any “step-wise reduction[[s]” were to to physical objects, not to sense-experiences. Of course, some readers may argue that we only gain access to physical objects via what occurs in the mind.