Did the biologist and naturalist E.O. Wilson “derive an ought from an is”?… Or did he ignore the ought entirely?

“Thus at least man comes to feel, through acquired and perhaps inherited habit, that it is best for him to obey his most persistent impulses. The imperious word OUGHT [my capitals] seems merely to imply the consciousness of the existence of a rule of conduct, however it may have originated.”

— Charles Darwin (From his Descent of Man — the actual passage is here.)

[Note: I wrote this essay some years ago (hence the square brackets) and would probably write it in a different way today. I even contemplated adding a question mark at the end of the title. That said, I don’t have any big problems with anything within it. Indeed, if I did have problems with it, then there’d be no point in publishing it here on Medium.

So to make things clear. I have no serious problems with evolutionary theory, applying the sciences to non-scientific issues, etc. In fact, broadly speaking, I’m a naturalist. So I have a lot of sympathy with the following passage from Daniel Dennett:

“If ‘ought’ cannot be derived from ‘is,’ just what can ‘ought’ be derived from? Is ethics an entirely ‘autonomous’ field of inquiry? Does it float, untethered to facts from any other discipline or tradition? Do our moral intuitions arise from some inexplicable ethics module implanted in our brains (or our ‘hearts,’ to speak with tradition)?”

That quoted, when it comes to ethics, I do believe that there are complications… as will hopefully be shown in the following essay.]

***************************

Edward Osborne Wilson (1929 — 2021) was an American biologist and naturalist.

Wilson was a humanist laureate of the International Academy of Humanism, a winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction and a New York Times bestselling author.

Wilson was widely recognized as one of the most important scientists of his generation. He received more than 150 awards and medals. (Several animal species have also been named in his honour.)

Finally, Wilson has been called “the father of sociobiology”. He also been called “the father of biodiversity” for his environmental advocacy. More relevantly to the following essay, his ideas on ethics and religion have been praised, criticised and much discussed.

E.O. Wilson’s Naturalised Ethics?

It’s not surprising that someone who believes in (universal) historical and scientific consilience should have believed that ethics is a suitable subject for for scientific scrutiny.

(Consilience: “the principle that evidence from independent, unrelated sources can ‘converge’ on strong conclusions”.)

So how did E.O. Wilson explain science’s relatively new-found interest in ethics? Wilson argued:

“The objective meaning of ethical precepts comprises the mental processes that assemble them and the genetic and cultural histories by which they evolved. Those who think that an is/ought gap exists have not reasoned through the way the gap is filled by mental process and history.”

This is a very interesting passage from Wilson. For example, what on earth do the words “the objective meaning of ethical precepts” mean?… Actually, it’s fairly clear what Wilson was getting at. Still, it’s just an odd use of the words “the objective meaning of”. In addition, Wilson even appears to completely misunderstand the “is/ought gap”…

Either that, or he simply dismissed it!

If Wilson did dismiss it, then good arguments and reasons would need to be given for such a dismissal.

In any case, clearly Wilson was putting a purely descriptive position on “ethical precepts”, not a normative one. Perhaps it follows (at least to some people) from this that it’s not ethics at all! Instead, it’s simply the scientific study of human ethics…

Wilson might well have dismissed that just-stated distinction.

In more detail, Wilson’s position can be seen as being purely scientific (which may not be a bad thing). That’s primarily because of statements such as the following:

“[E]thical precepts comprises the mental processes that assemble them and the genetic and cultural histories by which they evolved.”

Thus these passages are about what we (whoever “we” are) take ethical precepts to be — not what ethical precepts are or what they should be…

Again, Wilson might well have taken these distinctions to be entirely bogus.

So all this is similar to what naturalised epistemology is to traditional epistemology. Here, instead, we have (what seems to be) a naturalised ethics. However, if ethics is intrinsically normative, then perhaps it can’t ever be (fully) naturalised. (Yet no doubt natural phenomena can — and will — still come into the equation.)

Isn’t ethics about how we should live, not how we do live?

In that sense, then, Wilson’s position isn’t ethics at all. It’s the scientific (i.e., biological, neuroscientific, psychological, sociological, etc.) study of human ethics.

More concretely, if Wilson believed that ethics is the study of the “genetic and cultural histories by which [ethical precepts] evolved”, then we can’t do anything about such causal aetiologies of our ethical standards and principles. That’s obviously because such things have already happened. Therefore this is simply a causal account of what we believe and do in the ethical sphere.

Perhaps the study of the “mental process that assemble [our ethical precepts]” isn’t itself in the domain of ethics. Isn’t it the domains of the sciences?

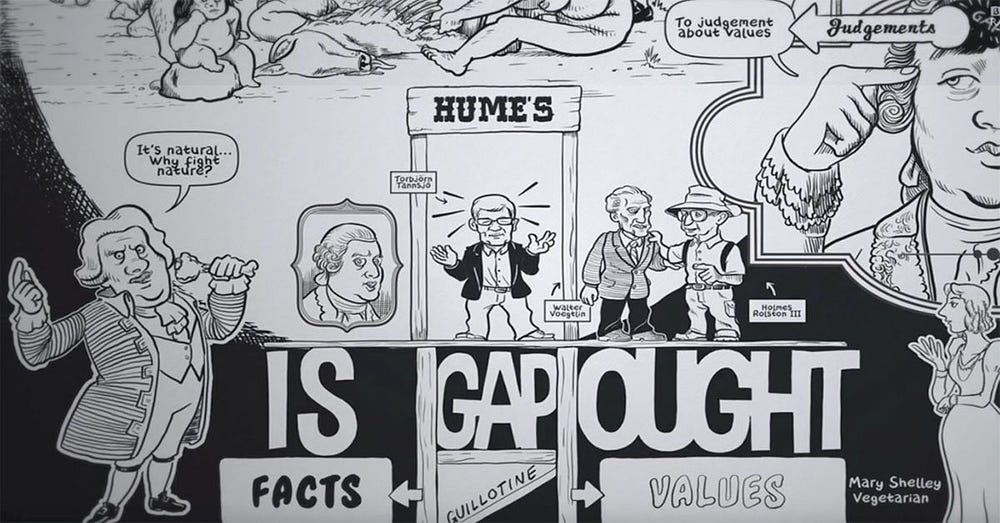

The Is-Ought Gap

Moreover, how is the is/ought gap (or is-ought problem) bridged simply by reasoning about this “mental process and history”?

All this is still the realm of the is and was, not the ought.

Just because we can fill in the gap (as Wilson put it) between the original causes of our beliefs and principles and the beliefs and principles themselves which followed, that alone doesn’t take us into the normative (or from the is to the ought) — even if the gap is filled with “mental processes and history” or whatever else. By filling in the causal gaps between causes and their effects (ethical precepts in Wilson’s book), then we still don’t take the ethical from the is to the ought (or from the descriptive to the normative).

So it seems very unclear why Wilson believed that the is/ought gap has been bridged or “filled’.

How will acquiring knowledge of the causes of our ethical precepts tell us whether or not our precepts are the right or the wrong ones? The causal or scientific facts of genetics (or whatever scientific data we can find) may help us understand why we hold our ethical precepts; though not why we should still hold them.

The English philosopher, writer and journalist Julian Baggini (1968 — ) sees some of these problems too. He writes:

“The idea here seems to be that ethical precepts — for example, the incest taboo — have their roots in particular genetic and cultural histories. It is clear that understanding such histories will be a useful tool in making ethical judgements. What is less clear is that this is a way out of the is/ought problem. After all, I ask [Wilson], are there not circumstances in which we will do well to struggle to behave in ways that might seem contrary to our natural instincts, as, for example, with respect to ethical precepts rooted in a mistrust of strangers or in aggression responses?”

We will indeed learn much from the aetiology of the incest taboo. However, we won’t learn whether or not that taboo is right or wrong from studying its “roots in particular genetic and cultural histories”. This knowledge, of course, may indeed help us in other ways. It will tell us, for example, that the taboo wasn’t passed down from heaven or that it’s not a non-natural precept which we somehow “intuit”. What’s more, all that scientific knowledge may — or will — indeed have an affect on our “ethical judgements”. However, that knowledge will not, at least not on its own, determine the conclusions of our ethical judgements…

So what will?

Wilson seemed to be arguing that we can indeed derive what we ought to do from what is (or what was) the case. That is, if something is genetically and/or culturally inscribed, then it must be a correct ethical precept.

But that clearly doesn’t follow.

Our natural instincts, for example, may be bad instincts. As Baggini puts it when he argues that

“we will do well to struggle to behave in ways that might seem contrary to our natural instincts, as, for example, with respect to ethical precepts rooted in a mistrust of strangers or in aggression responses”.

Of course certain natural instincts may also be good instincts. So it just depends…

No comments:

Post a Comment