“‘When we hear it said that wireless valves think,’ [Sir Geoffrey] Jefferson said, ‘we may despair of language.’ But no cybernetician had said the valves thought, no more than anyone would say that the nerve-cells thought. Here lay the confusion. It was the system as a whole that ‘thought’, in Alan’s [Turing] view…” — Andrew Hodges (from his book Alan Turing: the Enigma).

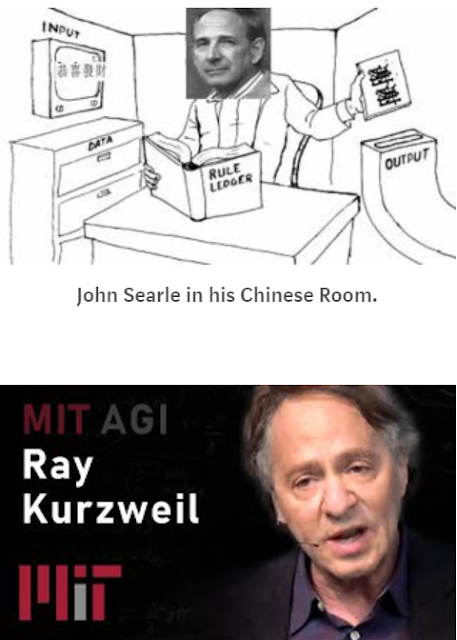

In his rewarding book, How to Create a Mind, Ray Kurzweil tackles John Searle’s Chinese room argument.

It’s a great book; though I do find its philosophical sections somewhat naïve. And that’s despite the book’s abundance of scientific and technical detail; as well as Kurzweil’s imaginative capabilities. Of course there’s no reason why a “world-renowned inventor, thinker and futurist” should also be an accomplished philosopher. That said, there’s also a danger of philosophers criticising him for not being so.

Kurzweil says, for example, that all his critics tend to know about Watson (an “artificially intelligent computer system capable of answering questions posed in natural language”) is that it’s a computer in a machine. He also says that some commentators don’t “acknowledge or respond to arguments I actually make”. He adds:

“I cannot say that Allen and similar critics would necessarily have been convinced by the argument I made in that book [The Singularity is Near], but at least he and others could have responded to what I actually wrote.”

The problem is that, in the case of John Searle’s Chinese room argument, the same can be said about Ray Kurzweil case against that. Sure, you wouldn’t expect a full-frontal and elongated response to Searle in a popular science book like How to Create a Mind. Having said that, there is a great deal of detail and some complexity — at least when it comes to other issues and subjects — to be found in this book.

The Argument

Ray Kurzweil’s argument against Searle is extremely basic. He simply makes a distinction between Searle’s man-in-the-Chinese-room and that man’s rulebook. Basically, the man on his own doesn’t understand Chinese. However, the man and the rulebook, when taken together, do understand Chinese.

So instead of talking about a man and his rulebook, let’s talk about the central processing unit (CPU) of a computer and its “rulebook” (or set of algorithms). After all, this is all about human and computer minds.

Firstly, Kurzweil says that “the man in this thought experiment is comparable only to the central processing unit (CPU) of a computer”. However, “but the CPU is only part of the structure”. In Searle’s Chinese room, “it is the man with his rulebook that constitutes the whole system”.

Again, “the system does have an understanding of Chinese”; though the man on his own doesn’t.

The immediate reaction to this is how bringing two things (a man and a rulebook) together can, in and of itself, bring about a system’s understanding of Chinese. Why is a system of two or more parts automatically in a better position than a system with only one part? (That’s if a system can ever have only one part.) How and why does multiplicity and (as it were) systemhood bring about understanding? It can be said that the problem of (genuine) understanding has simply been replicated. It may indeed be the case that the addition of a rulebook to either a man or a CPU brings about true understanding; it’s just that Kurzweil doesn’t really say why it does so.

John Searle is of course aware of what’s called the “system reply”. Nonetheless, he doesn’t really talk about the same system as Kurzweil. Instead of a man and a rulebook (or a CPU and a set of algorithms), Searle (in his paper ‘Minds, brains, and programs’) writes:

“Suppose we put a computer inside a robot…. the computer would actually operate the robot in such a way that the robot does something very much like perceiving, walking, moving about…. The robot would, for example, have a television camera attached to it that enabled it to ‘see’.”

As I said, this system isn’t the same as Kurzweil’s: its more complex and has more parts. Thus, on Kurzweil’s own reasoning, it should stand more of a chance of being a mind (or even person) than a computer’s CPU and its set of algorithms.

Searle then talks about putting himself in the robot instead of a computer. However, neither scenario works for Searle. It’s still a case that all Searle-in-the-robot is doing is “manipulating formal symbols”. Indeed Searle-in-the-robot is simply

“the robot’s homunculus, [he] doesn’t know what’s going on. [He doesn’t] understand anything except the rules for symbol manipulation”.

Again, how does systemhood alone deliver understanding?

Ned Block on Systemhood

The American philosopher Ned Block, on the other hand, offers us a system which is very similar to Kurzweil’s. He too is impressed with the systemhood argument. In his ‘The Mind as Software in the Brain’ he states that

“we cannot reason from ‘Bill does not understand Chinese’ to ‘The system of which Bill is a part does not understand Chinese’…”.

Block continues:

“[T]he whole system — man + programme + board + paper + input and output doors — does understand Chinese, even though the man who is acting as the CPU does not.”

Block adds one more point to the above. He writes:

“I argued above that the CPU is just one of many components. If the whole system understands Chinese, that should not lead us to expect the CPU to understand Chinese.”

Again, how does systemhood — automatically or even indirectly — generate understanding? Block hardly offers an argument other than complexity or that the addition of parts to a system may (or does) bring about understanding. Indeed he goes so far as to say that his own system could (or even does) have what he calls “thoughts”. He tells us that

“Searle uses the fact that you are not aware of the Chinese system’s thoughts as an argument that it has no thoughts. But this is an invalid argument. Real cases of multiple personalities are often cases in which one personality is unaware of the others”.

One part of Ned Block’s argument does seem to be correct. It doesn’t appear to be the case that

if Searle-in-the-system doesn’t know the thoughts of the entire system,

then consequently the system must have no thoughts either.

Nonetheless, the question still remains as to how mere systemhood brings about understanding. It doesn’t matter if the CPU or Searle-in-the-system does — or does not — know what the entire system is thinking (or understanding) if mere systemhood can’t bring about thoughts (or understanding) in the first place. In other words, Searle-in-the-system (or the CPU) may in principle be unable to know if the system as a whole has thoughts or understands things — and yet at the same time it’s still the case that it doesn’t actually have thoughts or understand things.

Kurzweil’s Computer-Behaviourism?

Kurzweil says something that assumes much in its simplicity. He writes:

“That system [of a man and his rulebook] does have an understanding of Chinese; otherwise it would not be capable of convincingly answering questions in Chinese, which would violate Searle’s assumption for this thought experiment.”

What Kurzweil seems to be arguing is that if the system answers the questions, then, almost (or literally!) by definition, it must understand the questions. Full stop. This is a kind of behaviourist answer to the problem:

If the system behaves “as if” it understands (i.e., by answering the questions),

then it does understand.

So it’s not even a question of behaving as if it understands. If the system answers the questions, then it does understand. That’s because if it didn’t understand, it couldn’t answer the questions!

Searle is of course aware of this behaviourist (or at least quasi-behaviourist) position. Basically, the problem of computer minds replicates the problem of human “other minds” (as in the Problem of Other Minds). As Searle himself puts it:

“‘How do you know that other people understand Chinese or anything else? Only by their behaviour. Now the computer can pass the behavioural tests as well as they can (in principle), so if you are going to attribute cognition to other people, you must in principle also attribute it to computers.’”

As I said, this raises all of Searle’s questions about true understanding — or, in his terms, meaning, intentionality and reference. To put Searle’s point in very basic terms: the system could answer the questions without understanding the questions. Though since Kurzweil is arguing that the very act of answering the questions quite literally constitutes understanding; then, by definition, Searle is wrong. Nothing, according to Kurzweil, is missing from this story.

So forget the man and his rulebook, let’s talk about the CPU and its rulebook (or set of algorithms) instead:

If the CPU and the rulebook answer the questions,

then the whole system understands the questions.

If it’s definitionally the case that answering the questions means understanding the questions, then Kurzweil is correct in his argument against Searle. Nonetheless, Searle knows that this is the argument and he’s argued against it for decades. There’s something left out of (or wrong about) Kurzweil’s position. So what’s wrong with it?

Kurzweil himself is aware — if in a rudimentary form — of what Searle will say in response. Writing of Searle’s position, Kurzweil says that

“he states that Watson is only manipulating symbols and does not understand the meaning of those symbols”.

It does indeed seem obviously the case that this is just an example of “manipulating symbols” and not one of true understanding. Having said that, that obviousness (or acquired obviously) is probably largely a result of reading Searle and other philosophers on this subject. If you have read more workers in artificial intelligence than philosophers on this subject, then it may seem to you that what Kurzweil argues is obviously the case.

So let’s forget intuition or obviousness.

Does a thermometer understand heat because it reacts to it in the same way each time? What I mean by this is that a thermometer is given a “question” (heat) and provides an “answer” (the rising or falling mercury). Sure, this understanding is non-propositional and doesn’t involve words or even symbols. But if Kurzweil himself sees these things in terms of the brain alone (i.e., its physical nature and output — not in terms of meaning or sentences), then why should that matter to him? In other words, if we can judge a computer squarely in terms of its output or behaviour (e.g., answering questions), then can’t we judge the thermometer in the same way? According to Kurzweil, if the computer answers questions then, by definition, it understands. Thus if the thermometer responds in the right way to different levels of heat, then it too understands. Thus sentences and their meanings are no more important to computers than they are to thermometers.

No comments:

Post a Comment