Sheldon Cooper (of The Big Bang Theory) sorrowfully said that he’d “devoted the prime of [his] life to string theory” initially because it “seemed so elegant at the time”. He then came to “realize [that he] was just a simple country boy seduced by a big city theory with variables in all the right places”.

This piece is about the fictional character Sheldon Cooper (yes, he’s got his own Wikipedia page!) and his farewell to string theory. More particularly, it’s based on episode 20 of series 7 of The Big Bang Theory, ‘The Relationship Diremption’, in which Sheldon experiences a reverse Damascene conversion.

The character Sheldon Cooper is (or was) a theoretical physicist who studied at The California Institute of Technology (Caltech). He also studied for a year at the University of Keighley’s renowned Cooking and Media Studies Department in the United Kingdom’s Republic of Yorkshire…

So, I suppose, this is just a bit of fun.

However, I still agree with the “software architect” and prolific contributor to Quora, Viktor T. Toth, who stated the following:

“[T]his sitcom does a better job in some ways than many popular science documentaries that I have seen. So, while ‘accurate’ is not the word I would use, Sheldon’s description is not nonsense. [] One of the reasons why I like The Big Bang Theory is that it does not disrespect the science that it mocks.”

Sheldon Cooper and String Theory

Sheldon Cooper had been committed to string theory since he was a young teenager (or, perhaps, since he was a foetus?) and remained committed to it during 12 seasons of The Big Bang Theory. The character Leonard Hofstadter himself said (in the episode featured here) that Sheldon had been working on string theory “for the last twenty years”. That would take Sheldon back to 1994, when he was only 14. (Despite being a lowly experimental physicist and Sheldon’s best friend, Hofstadter could make people literally disappear, turn treacle into pure gold and reverse time in his bathroom.)

Of course it needs to be said from the very start that Sheldon Cooper (or a real flesh-and-blood equivalent) being unhappy with his own research into string theory isn’t itself an absolute indictment of the theory. After all, if science is a communal activity, then string theory must also be a communal activity. Thus, one single individual giving up on string theory shouldn’t count for much — even if that individual is a self-proclaimed genius.

That said, not only Sheldon Cooper was unhappy with string theory back in 2014. Many physicists — including several Nobel prize winners — had already argued that string theory is a scientific dead-end. Yet, here again (i.e., as with Sheldon-the-individual-physicist), it’s not the case that simply because some — or even many — physicists are unhappy with string theory, then that must also mean that it really is a dead-end.

[Note: M-theory isn’t mentioned in this episode. However, a theoretical physicist working in 2014 would certainly have known about it. Indeed Sheldon himself refers to things which seem to be taken straight from M-theory, which dates back to 1995.]

Sheldon Cooper’s New Position on String Theory

Sheldon Cooper stated his new position (i.e., in 2014) on string theory in the following way:

“All right. I’ve devoted the prime of my life to string theory and its quest for the compactification of extra dimensions. I’ve got nothing to show for it, and I feel like a fool.”

He continued:

“I know. As hard as this is, I have to move on. I can’t keep postulating multidimensional entities and get nothing in return. I have needs, too.”

[For those nerds who’re interested in the “compactification of extra dimensions” and “multidimensional entities”, see here and here.]

Sheldon then gave a retrospective account of his youthful conversion to string theory:

“[String theory] seemed so elegant at the time, but now I realize I was just a simple country boy seduced by a big city theory with variables in all the right places.”

This chimes in with what many physicists themselves have stated over the last couple of decades.

Sociologically, it was indeed the case that in the 1980s (although Sheldon himself wasn’t born until 1980) many talented young physicists were encouraged (by their professors and teachers) to take up string theory.

Interestingly and kinda on the same theme, Sheldon’s rival, Barry Kripke, classed himself (in the same episode) as a “stwing pwagmatist”. What on earth is that? Kripke explained:

“I say I’m gonna pwove something that cannot be pwoved, I appwy for gwant money, and then I spend it on wiquor and bwoads.”

To which Sheldon responded:

“Do you think he is right? Am I wasting my life on a theory which can never be proven?”

All this happened largely as a result of the monumental claims and grand promises of string theory.

And now those formerly-young physicists are middle-aged (or older) tenured professors who’ve spent their entire professional lives devoted to string theory. (This is unlike Sheldon himself, who was about 33 — looking about 6 — in this 2014 episode.) So what else could these professors now do? And if they were to do something else, then would they still be able to pay their mortgages, go on as many holidays, etc?

Some of these issues can be found in Lee Smolin’s book The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next. This book also contains a chapter called ‘How Do You Fight Sociology?’, which is relevant here. (This chapter’s title could be misread as being against sociology — it’s not.)

Lee Smolin on the Sociology of String Theory

Lee Smolin’s The Trouble With Physics was written eight years before Sheldon’s own rejection of string theory in 2014.

In his blog post ‘Response to Criticism’, Smolin wrote the following:

“To discuss some sociological issues in contemporary academic science which I argue are slowing the progress of science, and to propose solutions to them.”

In The Problem With Physics itself and on string theory specifically, Smolin wrote:

“String theory is a powerful, well-motivated idea and deserves much of the work that has been devoted to it. [] The real question is not why we have expended so much energy on string theory but why we haven’t expended nearly enough on alternative approaches.”

It’s worth noting here that Smolin’s (as it were) sociological view of string theory isn’t original to him: it dates back to at least 1987. In that year, American theoretical physicist and string theorist David Gross made the following controversial comments (as quoted by Peter Woit — see later) about some of the reasons for the popularity of string theory:

“The most important [reason] is that there are no other good ideas around. That’s what gets most people into it. When people started to get interested in string theory they didn’t know anything about it. [] So I think the real reason why people have got attracted by it is because there is no other game in town. All other approaches of constructing grand unified theories, which were more conservative to begin with, and only gradually became more and more radical, have failed, and this game hasn’t failed yet.”

The theoretical physicist Peter Woit (in his book Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law) also viewed the academic, sociological and intellectual hegemony of string theory as being bad news for the future of fundamental physics. And perhaps even more sociologically, he argued that string theory’s popularity was at least partly a result of the financial and political nature of academia. More importantly and narrowly, the hegemony of string theory was partly — or even mainly — down to the mad academic competition for scarce resources.

In addition, in his book The Road to Reality, mathematical physicist Roger Penrose had this to say:

“The often frantic competitiveness that this ease of communication engenders leads to bandwagon effects, where researchers fear to be left behind if they do not join in.”

Some readers may now be wondering if the “string theory revolution” was itself a Kuhnian paradigm shift. The same readers may also wonder if it will take another revolution to shift away from string theory. That said, these claims may include a too broad and vague use of Thomas Kuhn’s notion of a paradigm shift. (Smolin himself discussed Kuhn on six different pages in The Problem With Physics.) And it will especially irk those physicists and philosophers who don’t accept this Kuhnian notion in the first place. Indeed it will also irk those string theorists who don’t see string theory as a paradigm shift at all. (String theory might well have been very important and also a huge advance in physics, yet still not have been a paradigm shift.)

In terms of Sheldon’s own history, psychology and sociology, his conversion to string theory was itself utterly contingent and based on happenstance.

Sheldon and the Emotional Appeal of String Theory

In the episode ‘The Relationship Diremption’, Sheldon admitted that he “didn’t seek out string theory”. Instead, string theory “just hit [him] over the head one day”. In detail:

“A bully chased me through the school library and hit me over the head with the biggest book he could find.”

That book was on string theory.

Of course this biographical account is a joke… with an element of sociological and psychological truth.

Like many physicists, the fundamental and all-encompassing nature of string theory appealed to the young Sheldon. Indeed this is the kind of thing which drives many theoretical physicists. For example, take someone like Michio Kaku and his — to be rhetorical for a moment - obsession with finding a “theory of everything” (what Kaku calls “the God Equation”), which, like Sheldon, dates back to his childhood.

Sheldon himself expressed his position in his usual highfalutin and dismissive way in the following:

“You want me to give up string theory for something that’s less advanced? You know, why don’t you break up with Penny and start dating a brown bear?”

So clearly Sheldon was still (i.e., in this episode) having second thoughts about giving up string theory.

Many physicists — and commentators! — might have said (at least in 2014) that Sheldon made the wrong move. They might have argued that most worthy theoretical physicists still knew that string theory is the only feasible way of going beyond the overall framework of quantum field theory. Indeed they’d have gone further than that and also have argued that when it comes to a unified theory, there’ve been no other viable alternatives to string theory. Basically, then, they’ll have stated that there’s simply no alternative to string theory… In fact many string theorists, over the years, have stated precisely that!

Of course string theorists — who include several Nobel prize winners — have fought back against all the criticisms. Among other things, they’ve told us that string theory has led to many important breakthroughs in both mathematics and in physics.

Sheldon and Fowler’s Super-Asymmetry Theory

Perhaps the biggest joke at string theory’s expense (in The Big Bang Theory) is the story of Sheldon Cooper and Amy Fowler Fowler publishing a paper on what they called “super-asymmetry”. This theory was meant to be true of (or refer to) precisely nothing in the actual (or real) world, but which nonetheless won them a Nobel Prize.

Of course super-asymmetry doesn’t actually exist in physics. What’s more, super-asymmetry (even if real) wouldn’t — strictly speaking — be a purely string theory… theory. However, it would still be closely related to string theory.

All that said, the script writers of The Big Bang Theory did talk to their “science consultant”, Professor David Saltzberg. They requested that Saltzberg come up with a fictional theory which was worthy of a Nobel Prize.

This is how Don Lincoln (a senior scientist at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory) put it:

“To begin with, there is no real theory called Super Asymmetry. However, there is a theory called supersymmetry, which is a very popular extension of the standard model of particle physics — our best current theory of subatomic matter. While there has been no experimental confirmation of supersymmetry — which proposes that every particle identified in the standard model has a supersymmetric partner — it is well enough regarded that there exist over 10,000 scientific papers on the topic. So, except for the poetic license on the name change, we’ll give them that.”

Dr. Saltzberg himself put it this way:

“Theoreticians love symmetrical equations, but the world around us is clearly asymmetrical. What theoretical physicists often do is create a theory with lots of symmetry, but then break it, to explain our world. [] The brilliance of Sheldon and Amy was to include asymmetry into their theory from the start.”

At the end of the series, Sheldon and Amy win the Nobel Prize (see here) for their super-asymmetry theory.

Final Note

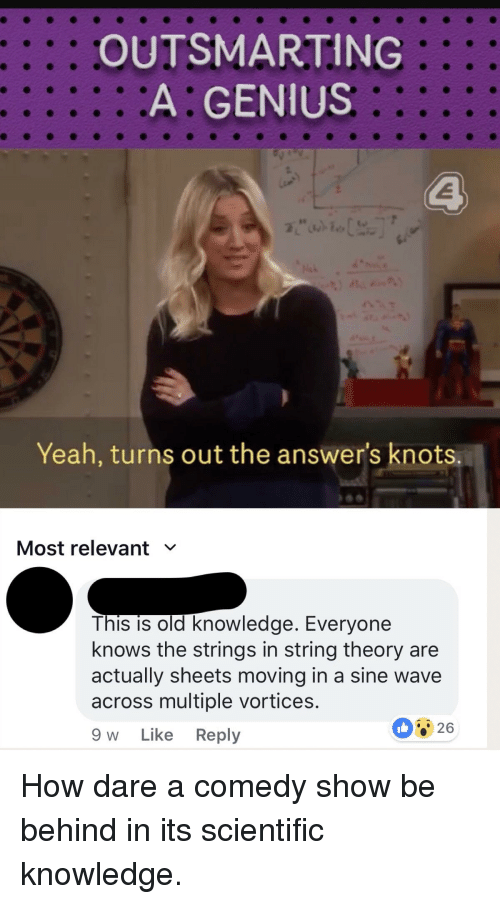

It’s now worth stating that in 2017 (i.e., some 4 years after the episode featured in this piece) Sheldon Cooper still seemed to be flirting with string theory. (See series 11 episode 13, The Solo Oscillation.) For example, his renewed excitement about string theory occurred during a conversation with Penny.

In that conversation, Sheldon explained (in response to Penny’s questions) that there are no knots in more than four dimensions. (See the mathematics here.) So, instead, he thought of them as sheets or branes. This shows us a partly fictitious addition to string theory (partly because branes were first discussed as early as the 1980s), which rode alongside the many (still fictitious?) additions which have been constructed by real-life string theorists.

No comments:

Post a Comment