Philosopher Mary Midgley once asked this question: “How will the language of physics convey the meaning of the sentence ‘George was allowed home from prison at last on Saturday’?” Steven Weinberg replied: “This criticism would strike home if there were physicists who were trying to use physics for such a purpose, but I don’t know of any.” Biologist and neuroscientist Gerald Edelman stated: “A person is not explainable in molecular, field-theoretical, or physiological terms alone.”… So who has actually claimed that a person is explainable in these ways alone?

“A reductionist analysis could decompose the words into their individual letters, the letters into the chemical constituents making up the black ink on white paper [] it would not tell you about the meaning of the letters combined as words, sentences, and paragraphs.”

— The English neuroscientist and science spokesman for the Socialist Workers Party Steven Rose (1938-) stating something that literally no one would ever attempt to do. (See source of quote here.)

Steven Weinberg (1933 — 2021) was an American theoretical physicist who won the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions (along with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Glashow) to the unification of the weak nuclear force and electromagnetism. His work on elementary particles and physical cosmology earned him many awards and prizes, including the 1991 National Medal of Science.

Weinberg was a professor at the University of Texas at Austin, where he was a member of the Physics and Astronomy Departments. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Britain’s Royal Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Weinberg also served as president of the Philosophical Society of Texas, a consultant at the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and the Council of Scholars of the Library of Congress. Weinberg received the Benjamin Franklin Medal of the American Philosophical Society in 2004. This society stated that he was “considered by many to be the preeminent theoretical physicist alive in the world today”.

Most of Steven Weinberg’s words in the following essay can be found in his article ‘Reductionism Redux’, which was originally published in The New York Review in 1995. This article itself can be found in Weinberg’s book, Facing Up: Science and Its Cultural Adversaries (2001).

Mary Midgley on Reductive Megalomania

In his book Facing Up: Science and Its Cultural Adversaries, Steven Weinberg discussed the British philosopher Mary Midgley (1919–2018) and her strong stance against reductionism. Weinberg primarily responded to Mary Midgley’s words as they can be found in her article ‘Reductive Megalomania’, which itself appears in the book, Nature’s Imagination: The Frontiers of Scientific Vision.

Mary Midgley asked the following questions:

“‘What, for instance, about a factual statement like ‘George was allowed home from prison at last on Saturday?’ How will the language of physics convey the meaning of ‘Sunday’? or ‘home’ or ‘allowed’ or ‘prison’? or ‘at last’? or even ‘George’?’”

Weinberg responded to this passage by saying that

“[t]his criticism would strike home if there were physicists who were trying to use physics for such a purpose, but I don’t know of any”.

Indeed one must try and give Midgley the benefit of the doubt here and assume that she must have been discussing (as it were) possible reductionism. Thus, perhaps Midgley simply meant that reductionism could go down this rabbit hole if we (or if scientists) weren’t careful. So perhaps she wasn’t actually claiming that any physicists have attempted to reduce statements like “George was allowed home from prison at last on Saturday” to physics — yet she still believed that this could be the case if we don’t watch out.

As it is, it can be doubted that this last interpretation is correct. Why is that? It’s because this is precisely how many self-styled anti-reductionists do see reductionism — with its (to use E.O. Wilson’s words) “hissing suffix”.

Weinberg didn’t go into much philosophical and/or scientific detail about Midgley’s words. So I’ll need to add some details myself.

Firstly, no physicist would ever even attempt to reduce the sentence “George was allowed home from prison at last on Saturday” (or even the referents of any of the words within it) to physics because that sentence and its contents simply aren’t in the domain of physics. (Mary Midgley herself didn’t explain why she believed that some — or any — physicists would want to reduce that sentence to physics.)

That last statement about not reducing “George was allowed home from prison at last on Saturday?” to physics isn’t an expression of what anti-reductionists would warn reductionists against. No physicist himself would deem this area to be the domain of physics. Indeed the very idea of reducing the event (let alone the previous sentence) of George being let out of prison, George himself, a prison, Saturday, etc. to physics seems ridiculous.

Weinberg himself spots the problem with Midgley’s position or at least what her position can lead to or what it may imply. Although he didn’t state that Midgley held this position herself, Weinberg did claim that

“many of our fellow citizens think that George behaves the way he does because he has a soul that is governed by laws quite unrelated to those that govern particles or thunderstorms”.

What now needs to be said is that many non-religious philosophers and laypersons also take this position without also believing in a soul (at least as the soul is seen in various religions). Arguably, all (or at least most) anti-physicalists do take the position expressed by Weinberg directly above. However, in order to see that all the reader needs to do is take out the word “soul” and substitute it with the word “mind”, “consciousness” or “person”.

[In a few moments it will be seen that Gerald Edelman did indeed use the word “soul” in his article, ‘Memory and the Individual Soul: Against Silly Reductionism’.]

To get back to Mary Midgley.

So who, exactly, was Midgley arguing against and warning us about?

Perhaps it was the English molecular biologist and neuroscientist Francis Crick (1916–2004).

More accurately, perhaps it was a very-well-known passage from Crick which has been quoted innumerable times (nearly always negatively or critically). In fact, if readers Google the passage, there are 19 pages of links (with 10 entries on each page — that’s 190 separate links) to papers, articles, essays, books, etc. which fully quote Crick’s words (see here).

That infamous passage can be found in Francis Crick’s 1994 book, The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul. So here goes:

“‘You’, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”

And, guess what, Mary Midgley did indeed refer (more than once) to this passage from Crick! For example, she did so in her book Are You an Illusion?. (See also her references to it in the Guardian, New York Times and Philosophy Now — see here, here and here.)

I myself have quoted this passage twice (in two essays) in recent months and other times over the years. (See my ‘Francis Crick’s Deliberately Provocative Reductionism’.)

So this passage was worth quoting again simply because I suspect that it is the main — perhaps exclusive — source of what many anti-reductionists take reductionism to be (or, at the very least, what they believe it can be).

However, to add something new here (i.e., something not in my previous essay on Crick), it can be said that even in those infamous words above, Crick isn’t literally advising reducing “‘you’, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will” to the brain, neurons, biochemistry or to anything else — at least not explicitly.

But, firstly, it must be said that Crick’s phrase “no more than” is problematic. It is vague. And it may well be simply metaphorical or rhetorical too.

More relevantly to the issue of reductionism.

Stating that “x is no more than y” isn’t also an explicit claim that x can be reduced to y. (See final section on physical entailment.) It can mean this in that in some cases a given x could be reduced to y. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean that. That is, x may be no more than y even though it would still be impossible to (fully) reduce x to y. (Perhaps for reasons of complexity, the difficulties of “inter-theoretic” reduction, the clash of concepts from different disciplines, etc.)

Steven Weinberg also focusses on Francis Crick’s fellow biologist and neuroscientist Gerald Edelman and his now widely-known stance against what he called “silly reductionism”.

Gerald Edelman on Silly Reductionism

Gerald Edleman’s following words also appear in the same book as Midgley’s (i.e., in Nature’s Imagination: The Frontiers of Scientific Vision). His article is called ‘Memory and the Individual Soul: Against Silly Reductionism’.

Steven Weinberg quoted Gerald Edelman putting his general position against the

“kind of reductionism that doomed the thinkers of the Enlightenment is confuted by evidence that has emerged both from modern neuroscience and from modern physics”.

It can be doubted that were many scientists and philosophers in the 20th century — or even in the 19th century — who believed the kinds of things Gerald Edelman stated that they believed. (I’m willing to be contradicted on that because you can always find extreme or silly positions — on literally any subject — if one looks hard enough for them.)

In any case, Edelman continued:

“‘[A] person is not explainable in molecular, field-theoretical, or physiological terms alone. To reduce a theory of an individual’s behavior to a theory of molecular interactions is simply silly. [] Even given the success of reductionism in physics, chemistry, and molecular biology, it nonetheless becomes silly reductionism when it is applied exclusively to the matter of the mind.’”

Now for a simple question:

Has any reductionist (or person deemed to be a reductionist) ever claimed that a person — yes, person — is “explainable in molecular, field-theoretical, or physiological terms alone”?

… Other than, say, Francis Crick (as already discussed)?

More specifically, since when has any scientist who deals with molecular chemistry, field theory or physiology ever taken persons to be their subject matter?

So let’s concentrate on two important words used by Edleman: “person” and “alone”.

Personhood (or the nature of a person) is a philosophical subject and term which, at the most, has been covered by social scientists.

What’s more, even if a field theorist, chemist or physiologist did tackle the nature and status of a person, would he or she claim that field theory, chemistry or physiology (to use Edleman’s word) “alone” would provide a complete explanation of such a thing?

Like Weinberg, I personally haven’t come across any field theorist, chemist or physiologist who’s made such claims…

So perhaps it has been others — i.e., people who aren’t natural scientists — who’ve made these claims. Perhaps, say, philosophers or scientists of other disciplines have done so. This would mean that such philosophers and/or scientists have used the data of field theory, chemistry and physiology to advance their claims that persons are (literally) fields or chemical and/or physiological mechanisms alone…

Yet even this can be doubted because it would entail a literal identity between a given person and his fields or his chemicals and/or physiological mechanisms.

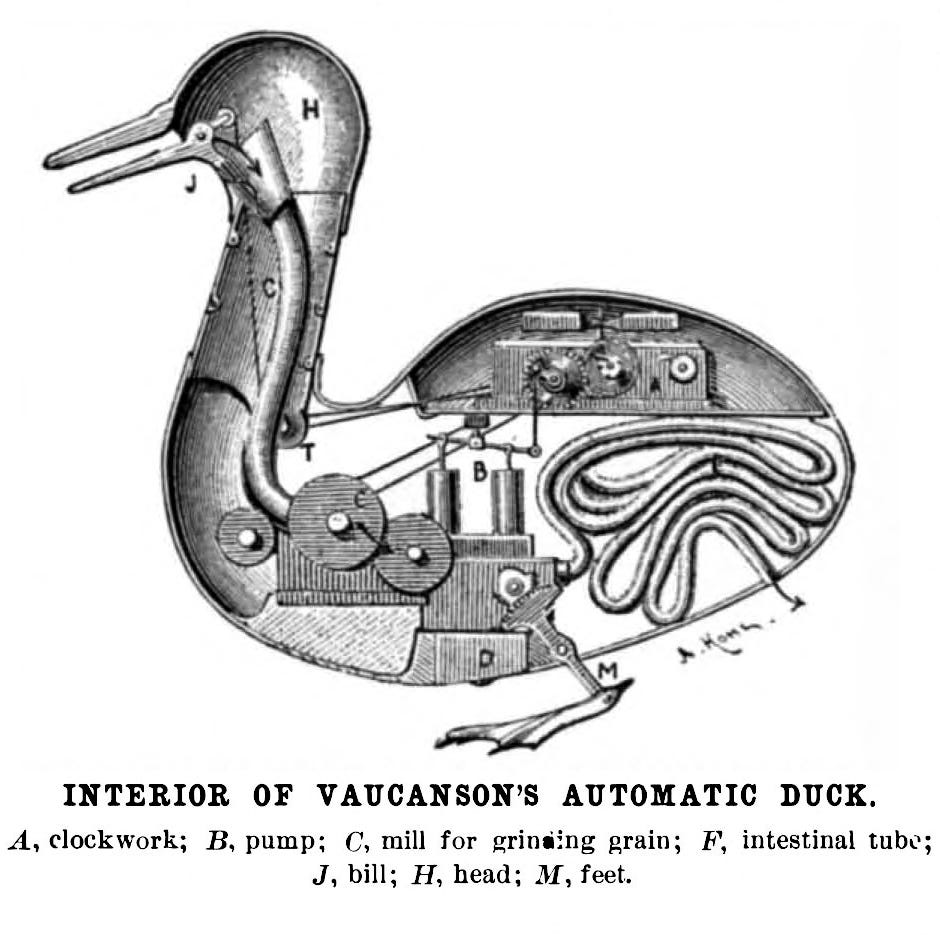

Weinberg himself goes into detail on Edelman’s position here:

“When Edelman says that a person cannot be reduced to molecular interactions, is he saying anything different (except in degree) than a botanist or a meteorologist who says that a rose or a thunderstorm cannot be reduced to molecular interactions?”

So why is such a reduction of a rose or a thunderstorm (to put it modally and strongly) impossible?

Well, Weinberg goes on to say that

“[i]t may or may not be silly to pursue reductionist programs of research on complicated systems that are strongly conditioned by history, like brains or roses or thunderstorms”.

This means that the complexity of a given system itself can’t be fully explained in the language of atoms, particles, forces and fundamental laws, and neither can the contingencies of its history.

More relevantly, what isn’t silly is the

“perspective [] provided by reductionism, that apart from historical accidents these things ultimately are the way they are because of the fundamental principles of physics”.

So was all this a case of Edleman tilting at windmills?

And was Edelman doing so simply to prove that he wasn’t a boneheaded reductionist? And if Edleman did want to prove that, then why did he do so?…

Perhaps Edelman did so because reductionism was precisely what he himself had previously been accused of on a few occasions! (This was before he was seen as being an anti-reductionist — see here, here and here.)

Interestingly enough, Steven Weinberg himself — just like Edelman — did appear to offer a single exception to his general reductionism: the human person. Or more specifically: consciousness.

Steven Weinberg on Persons and Consciousness

Take this passage from Weinberg:

“But it seems to me that [Peter] Atkins is not sufficiently sensitive to the problems surrounding consciousness. I don’t see how anyone but George will ever know how it feels to be George.”

It’s not clear if how it feels to be George could ever be the subject of any reduction. One important reason for that is that it’s not even clear what phrases like “how it feels for George” mean.

In any case, there have been many philosophers (if not scientists) who’re both naturalists and physicalists and who also fully accept the first-person perspective on things. (The philosopher Owen Flanagan is a very good example of this. See my ‘Yes, Thomas Nagel, x can’t know what it’s like to be y’.) They also accept that first-person perspectives can’t be reduced. That said, they also believe that this fact (if fact is the right word here) most certainly doesn’t work against either physicalism or naturalism.

So do self-styled reductionists also accept all this?…

Prima facie, it’s not entirely clear that Steven Weinberg himself ruled out a reduction of consciousness or the human person to physics because he did continue with the following words:

“On the other hand, I can readily believe that at least in principle we will one day be able to explain all of George’s behavior reductively, including what he says about how he feels, and that consciousness will be one of the emergent higher-level concepts appearing in this explanation.”

This seems to be Weinberg putting Daniel Dennett’s heterophenomenological position (see ‘Heterophenomenology’). This isn’t to say that Weinberg knew about Dennett’s position. However, it is very similar to it.

It would be best, then, to split the passage above into two parts.

The first part is Weinberg’s advocacy of heterophenomenology:

“I can readily believe that at least in principle we will one day be able to explain all of George’s behavior reductively, including what he says about how he feels [].”

But then Weinberg seems to go beyond Dennett when he concluded:

“[C]onsciousness will be one of the emergent higher-level concepts appearing in this explanation.”

To Dennett, a scientist or philosopher can — and should — happily analyse what George says about “how he feels”. He can even analyse George’s own personal — and perhaps philosophical — words about his own consciousness and mind. That said, the scientific or philosophical heterophenomenologist still won’t be analysing George’s actual feelings, consciousness and mind: he’ll be analysing what George says about these things. (Some people interpret Dennett as holding the position that what George, heterophenomenologists and scientists say about x actually is x.)

All that said, would Dennett also accept (as Weinberg did) that consciousness is (to use Weinberg’s words) “one of the emergent higher-level concepts”? Indeed does Dennett accept consciousness at all?…

Well, Dennett both does and does not accept consciousness. That’s primarily because it all depends on how he — and others — define the term “consciousness”.

What’s more, there’s a big difference between “emergent higher-level concepts” and emergent higher-level… things. That is, the concept [consciousness] may well be useful. However, consciousness may still not be a thing or even a process (i.e., depending on definitions).

To Dennett (if not to Weinberg), consciousness isn’t anything above and beyond (to use Weinberg’s own words) “George’s behavior [and] what he says about how he feels”. (Saying things is a form of behaviour.) More accurately, consciousness isn’t above and beyond anything heterophenomenologists, scientists and/or philosophers could glean from George’s bodily behaviour, history and environment, his verbal statements, his brain and body, etc.

Jackson, Chalmers and Weinberg on Physical Entailment

The philosopher Frank Jackson’s position is also fairly close to Steven Weinberg’s, at least as it’s advanced in the following:

“But it is quite another question whether they must hold that θ a priori entails everything about our psychology, including its phenomenal side, and so quite another question whether they must hold that it is in principle possible to deduce from the full physical story alone what it is like to see red or smell a rose — the key assumption in the knowledge argument that materialism leaves out qualia.”

Frank Jackson’s first clause above (i.e., “that θ a priori entails everything about our psychology”) expresses a position which is similar to Weinberg’s. Yet, more concretely, Weinberg didn’t also believe (as we’ve seen with the discussion about George) “that it is in principle possible to deduce from the full physical story alone […] what it is like to see red or smell a rose”.

Thus, here we have a clash (or simply a difference) between entailment and deduction. More clearly, the physical may entail (to put it grandly) everything in the sense that without the physical (as well as everything about the physical) there would be no feels or (I dare say) qualia. However, from our current — and perhaps future — knowledge of the physical, we still can’t know everything.

[It may be questioned whether there can be such a thing as physical entailment for the simple reason that entailment is usually a logical term used exclusively about statements/propositions, symbols, equations, etc.]

Weinberg himself expressed this position (though he didn’t discuss consciousness or persons) in the following passage:

“Each science deals with nature on its own terms because each science finds something else in nature that is interesting.”

But he then continued:

“Nevertheless, there is a sense that the principles of statistical mechanics are what they are because of the properties of the particles out of which bodies are composed.”

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers (1966-) also made a distinction between entailment and deduction. (He didn’t use the word “deduction”.) He wrote:

“I am making the much weaker claim that high-level facts are entailed by all the microphysical facts (perhaps along with microphysical laws).”

These “high-level facts” (or Weinberg’s “emergent higher-level concepts”) aren’t themselves “microphysical facts”. They are entailed by the microphysical facts. This means two things:

(1) Without x’s microphysical facts, there would be no high-level facts when it comes to x.

(2) x’s microphysical facts (along with their entailments) alone don’t tell us everything. (They don’t, in this case, tell us about x’s high-level facts.)

There’s still a slight divergence in terminology here.

Whereas Weinberg uses the (philosophical) term “emergent”, Chalmers uses the term “supervene”. But that’s not an immediate problem. It can now be said that Weinberg’s “emergent higher-level concepts” supervene on the lower-level microphysical facts…

Yet there’s still one problem here which has already been mentioned.

Weinberg’s concepts can’t supervene on anything (except in a vague or metaphorical sense). Only things, conditions, properties, etc. can do so. In any case, it’s clear that Chalmers himself wasn’t discussing concepts in the words quoted above. He was discussing higher-level “properties, facts and laws”. So concepts emerging at a higher level is very different to things emerging at a higher level. Indeed higher-level concepts can (as it were) emerge without any actual physical emergence.

So it’s clear that Weinberg’s words “emergent higher-level concepts” are metaphorical (at least the word “emergent” is). Indeed, elsewhere Weinberg concedes this when he tells us that “new concepts ‘emerge’ when we deal with fluids or many-body systems”. Weinberg puts scare quotes around the word “emerge”. This means that when, say, things get complex, then new concepts may — or will — emerge. That is, such new concepts may be required to understand and explain things. However, that complexity may not have also resulted in any genuine physical emergence.

No comments:

Post a Comment