Albert Einstein once referred to the traditional view of science as one which posited a “continuous process of induction” and “the compilation of a classified catalogue”. He believed that this view “slurs over the important part played by intuition and deductive thought”.

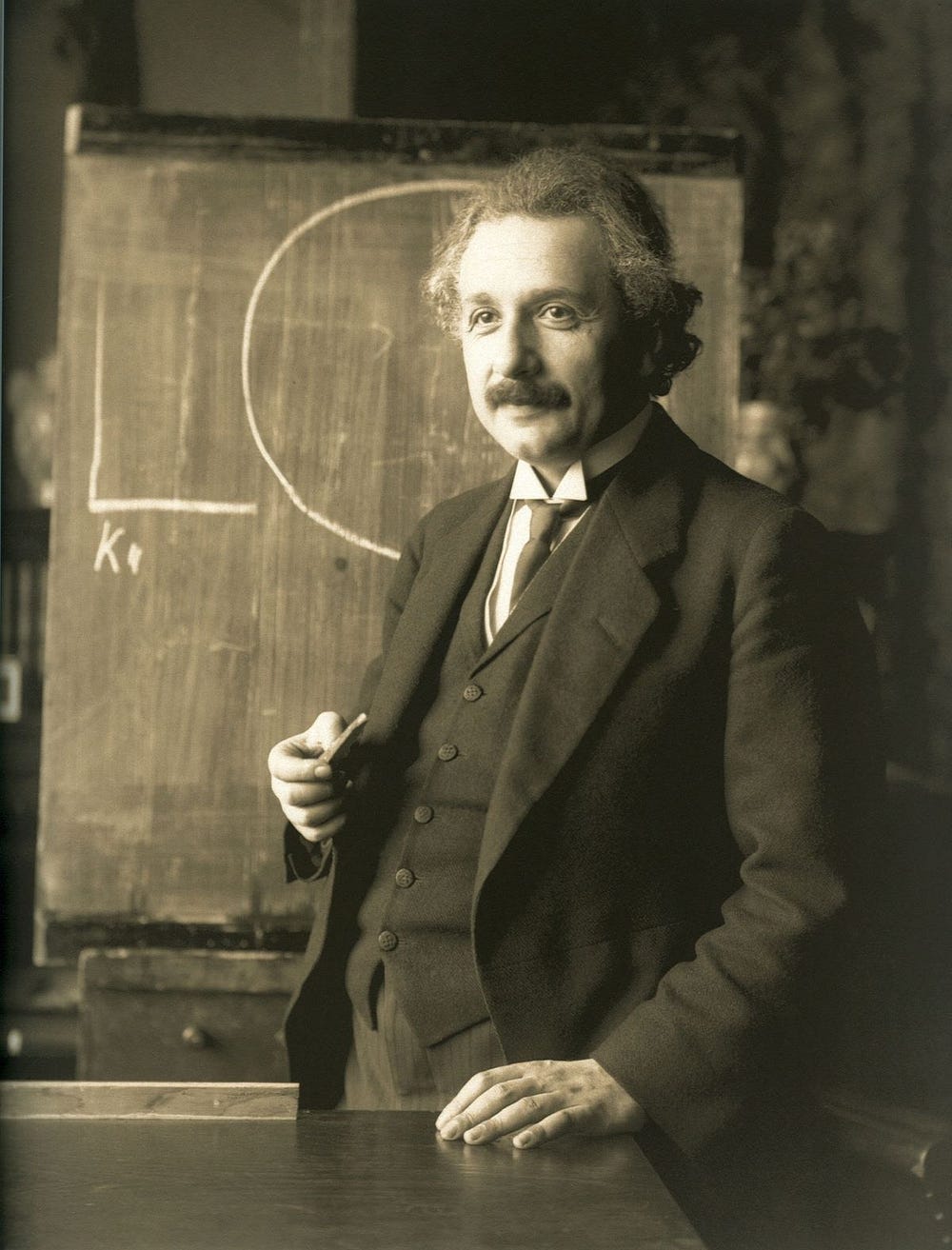

In 1916, Albert Einstein offered his readers an account of what he believed traditional scientists — and most laypersons — took science to be.

Firstly, he mentioned the stress on induction. He wrote:

“From a systematic theoretical point of view, we may imagine the process of evolution of an empirical science to be a continuous process of induction.”

The basic take on science is that it is essentially inductive. Or at least this is what’s usually believed (i.e., by some scientists and philosophers) to be the contemporary layperson’s view. The problem here is that most laypersons don’t actually philosophise about science at all. More particularly, they rarely — if ever — use the word “induction” or “inductive”. That said, some philosophers tell us that a person may have the concept of a word without ever actually using the word itself. Thus, laypersons may have the concept [induction] without ever using the word “induction”.

What’s more likely is that traditional scientists — and laypersons — stressed observations. So Einstein continued:

“Theories are evolved and are expressed in short compass as statements of a large number of individual observations in the form of empirical laws, from which the general laws can be ascertained by comparison.”

Thus, “individual observations” are (or were) often believed to drive the entire scientific show.

[Once again, only empirical research can establish what most (or any) scientists and laypersons actually believe. Yet, anecdotally, this does seem to be the usual position.]

On this (as it were) naive picture of science, then, scientists simply go outside and … well, observe. Alternatively, scientists carry out experiments and then simply observe what happens.

Thus, according to Einstein’s take on the traditional take, scientists collect all their observations together into a large pot (or at the least they collect their “statements” about their observations together), and then they attempt to make sense of them. Or, in Einstein’s own words, scientists extract “empirical laws” (exclusively?) from their observations.

Clearly, innumerable other factors would be required in order to extract empirical laws from observations alone. And then the situation becomes even more complicated when “general laws” are “ascertained” from those observations and empirical laws.

So Einstein was correct to detect the naivety of this view of science. And that’s why he went on to write the following words:

“Regarded in this way, the development of a science bears some resemblance to the compilation of a classified catalogue. It is, as it were, a purely empirical enterprise.”

Thus, scientists are (or at least were) often seen as merely cataloguing nature (or cataloguing their observations of nature). This is almost like scientific (as it were) “stamp collecting”. (As is the case with some accounts of Francis Bacon and his own philosophy of science. See here.) If this process is followed, then, it was believed that everything could be kept scientifically kosher — or empirical. (The reader might have detected unwritten scare quotes around Einstein’s use of the word empirical.)

Of course, one can immediately ask why scientists were cataloguing the things they were in the first place. Why were they observing those parts of nature and not other parts? Why did they want to “compile[]” the things they compiled and not other things? In other words, there must have been prior factors — above and beyond what it is they observed — that brought about those very same observations.

Einstein himself then explained why this view is both simplistic and naive. He continued:

“But this point of view by no means embraces the whole of the actual process ; for it slurs over the important part played by intuition and deductive thought in the development of an exact science.”

It’s clear, however, that Einstein wasn’t actually entirely ruling out the traditional view of science. This meant (to Einstein) that observations — and even cataloguing — are indeed part of the story of science. That said, these things, according to Einstein, “by no means embrace[] the whole of the actual process”. And it’s here that Einstein adds “intuition and deductive thought [to] the development of an exact science”.

Einstein also wrote the following:

“The theory finds the justification for its existence in the fact that it correlates a large number of single observations [].”

That reference to a “correlat[ion] of a large number of single observations” is a perfect account of a particular kind of inductive process — enumerative induction.

For example, from the observation — and then correlation — of a large number of white swans, a subject may (or will ) conclude that “all swans are white”. Alternatively, a scientist may develop a (to use Einstein’s word) “theory” about swans and why they are all white. (This may even include natural laws of some kind.)

Einstein had also already mentioned “induction” (though in a critical way) when he wrote:

“we may imagine the process of evolution of an empirical science to be a continuous process of induction”.

One may now ask exactly how a scientist “correlates a large number of single observations”. (Alternatively: How does a scientist — or anyone else - connect the dots about all swans being white?) After all, if the theory “finds its justification [in the] fact that it correlates a large number of single observations”, one may suggest that theories were already required in order to enable those correlations. In simple terms, then, old and accepted theories would have been required (or needed) in order to find a new theory. In the white swans case, in order to conclude that all swans are white, the person who concluded that must have already accepted various other things about swans, the colour white, the whiteness of swans, the nature of observations, biology, ornithology, etc.

Einstein on Intuition and Deductive Thought

Earlier, Einstein was quoted stating that the naive view of science (i.e., discussed so far)

“slurs over the important part played by intuition and deductive thought in the development of an exact science”.

Einstein’s stress on what he calls “intuition” and “deductive thought” is a little odd. Many philosophers of science and scientists today would stress theory here — not intuition and deductive thought. Of course, theory may also be intimately tied to both intuition and deductive thought.

So, firstly, what about the word “intuition”?

In philosophy and mathematics, that word often has very specific and technical meanings (see here). So one wonders if Einstein used it in one of those technical ways himself. Perhaps, instead, Einstein simply meant speculation and/or theorising by the word “intuition”. That is, intuition (at least within a scientific context) is all thought which goes above and beyond the observational data. Indeed, intuition may also be required to make sense of the observations, and even lay the groundwork for observations.

So what about Einstein’s words “deductive thought”?

In a general and perhaps vague sense, if we have observations (or statements about them), then we can deduce things from those observations. That is, the observations don’t simply stand on their own. Scientists need to make sense of them. In addition, scientists can also deduce (not always logically) other (what Isaac Newton called) “conclusions” from them.

However, Einstein himself wrote that

“the investigator develops a system of thought which, in general, is built up logically from a small number of fundamental assumptions, the so-called axioms”.

The quote directly above is Einstein (at least provisionally) treating physics as a kind of (pure) deductive logic. That is, instead of premises from which a conclusion can be derived (or axioms in mathematics which lead to theorems), we have observations and/or “fundamental assumptions” which lead to theories. And, in fact, Einstein himself says that “[w]e call such a system of thought a theory”.

Of course, much of what Einstein wrote about the traditional view of science is too neat and tidy. That is, scientific thinking and scientific practice didn’t really — or didn’t always — adhere to his retrospective formulations. But that’s often what happens in the philosophy of science.

My flickr account.

No comments:

Post a Comment