The British academic and literary critic Catherine Belsey wrote a book called Poststructuralism: A Very Short Introduction. That book doesn’t mention either (historical) idealism or (20th century) linguistic idealism. Perhaps Belsey would have seen such a mention as being out of place in an introductory book. However, this essay argues that linguistic idealism is at the very heart of poststructuralism. Indeed, Belsey’s own (very positive) words about poststructuralism show that to be the case.

[See my next essay, ‘Linguistic Idealism as a Weapon of Poststructuralist/Postmodernist Politics’.]

This essay is largely based on an extremely positive account of poststructuralism by the academic and literary critic Catherine Belsey (who died in 2021).

In her book Poststructuralism: A Very Short Introduction, Belsey waxes lyrically about literally all the theorists and philosophers she personally associates with poststructuralism. Oddly enough, Belsey includes the Stalinist Louis Althusser (who she had a soft spot for — see note at the end of this essay) and the self-described “communist” Slavoj Žižek (see ‘Why I am a communist but NOT a socialist’) under the poststructuralist banner. In other words, Belsey doesn’t just mention Althusser and Žižek in passing.

Belsey’s book is easy to read, as well as being entertaining. So it’s unlike the other books I’ve read on the subject of poststructuralism. Indeed, these books are often as hard to read as poststructuralism itself…

Yes! I’m happily and openly admitting that the other books on poststructuralism I’ve tried to read are ̶f̶a̶r̶ ̶t̶o̶o̶ ̶h̶e̶a̶v̶y̶,̶ ̶d̶e̶e̶p̶ ̶a̶n̶d̶ ̶e̶s̶o̶t̶e̶r̶i̶c̶ ̶ for me to understand.

So that’s the main reason why I’ve relied on Belsey’s book.

Again, Poststructuralism: A Very Short Introduction is easy to read and entertaining. However, it will be argued that it’s also flawed —at least from a philosophical point of view.

In critical terms, even most introductory books take some time to make clear what at least some of the criticisms of the philosophers and theorists discussed are. However, this isn’t the case with Belsey’s book.

So literally every theorist and philosopher Belsey associates with poststructuralism (including Barthes, Kristeva, Lacan, Derrida, Foucault, Althusser, Žižek and Lyotard) is given an extremely-positive spin.

Now Belsey’s omnipresent positivity toward all poststructuralists (at least the ones she discusses) can’t simply be because her book is a “very short introduction”.

Indeed, it isn’t.

Catherine Belsey was clearly (some kind of) poststructuralist herself.

This positivity is shown throughout Belsey’s book, as well as in her other publications, and the institution she ran.

Belsey chaired the Centre for Critical and Cultural Theory at Cardiff University from 1988 to 2003. And Wikipedia tells us that her book Critical Practice (1980) “was an influential post-structuralist text in suggesting new directions for literary studies”.

In any case, it’s crystal clear that Belsey was very far from being a non-biased commentator on poststructuralism.

Linguistic Idealism?

Some of the explanations and definitions of linguistic idealism are as vague as Catherine Belsey’s own hints at it (as we shall see).

For example, we have the claim that linguistic idealism is “the thesis that the world is a product of language”. (Here we see the vague words “product of”, which can be interpreted in many ways.)

We also have less vague — and, correspondingly, less radical — accounts, such as writing about Hegel’s “emphasis on the importance of linguistics in shaping cognition”. Indeed, this passage (from a paper called ‘Transcendental Versus Linguistic Idealism’) continues in the following manner:

“This view — linguistic idealism — redirects philosophy’s search for origins away from transcendental faculties and toward the history not of what we can know but of what we can say: toward the evolution of our basic words.”

That first sentence (at least as it stands) needn’t be taken as a commitment to linguistic idealism at all…

However, we need to establish what linguistic idealism is in the first place before we can say that such selected passages are — or are not — examples of linguistic idealism.

Similarly, the continued passage above needn’t be taken as an account of linguistic idealism either — even though it contains the words “linguistic idealism”! Thus, is the Wittgensteinian phrase “what we can say” (not “what we can know”) really any kind of commitment to linguistic idealism?

Well, yes and no.

It depends, again, on how we define the term “linguistic idealism” or what we take linguistic idealism to be.

So why is the term “linguistic idealism” used in this essay?

This term is used primarily because it’s the most suitable term available.

Thus, that’s not to say that readers need be entirely happy with it. What’s more, it’s certainly the case that poststructuralists themselves wouldn’t have liked it as a description of what it is they offered…

The main reason for that would be that idealism (in all its forms) is a historical Western position. (It can can be found in non-Western traditions too.) Yet poststructuralists are (or were) against the Western tradition.

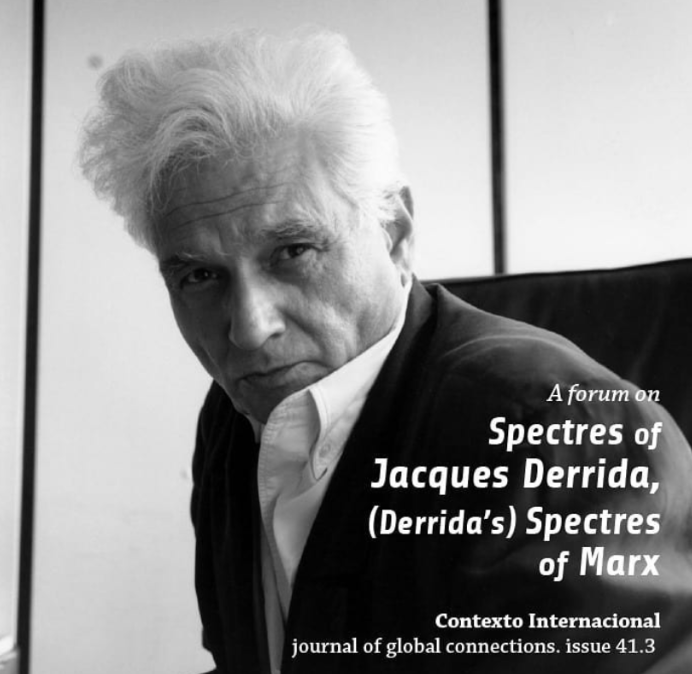

Thus, simply gluing the word “linguistic” onto the word “idealism” wouldn’t have been acceptable to a poststructuralist (especially a philosopher like Derrida). Furthermore, poststructuralists would never have dreamed of classing themselves as any kind of idealist…

Indeed, many (even most) poststructuralists didn’t even use the term “poststructuralist” about themselves. (“The play of the sign” goes on.)

Belsey herself tells us that Slavoj Žižek “rejects the label ‘poststructuralist’ (energetically)”.

Why is that?

It’s because he

“associates it with Derrida and what he sees as an exclusive and probably frivolous preoccupation with the signifier”.

In detail.

Poststructuralists set out to trump the entire “Western tradition”. (As stated, idealism has been prominent in non-Western traditions too.) Thus, using the word “idealism” about their own position/s was always out of the question.

All that said, this is the position of poststructuralists themselves on the term “linguistic idealism”. So there’s no reason why people who aren’t poststructuralists should accept such denials. In other words, simply because poststructuralists deny that they are linguistic idealists, then that doesn’t also mean that they aren’t linguistic idealists.

So perhaps a little context will help here.

Idealists (linguistic or otherwise) have often pitted themselves against realists. (Less often, and usually in the context of analytic philosophy, realism is itself pitted against anti-realism.)

Catherine Belsey herself recognised that poststructuralists (Lyotard in this instance) have pitted themselves against philosophical realism.

Firstly, she tells us that Jean-François Lyotard's “target” was “realism”.

Why did Lyotard target realism?

Belsey continued:

“Realism, [Lyotard] claims, reaffirms the illusion that we are able to seize hold of reality, truth, the way things ‘really’ are.”

Lyotard (as expressed by Belsey) went even deeper when he argued that realism “protects us from doubt”. In Belsey’s words:

“[Realism] offers us a picture of the world that we seem to know, and in the process confirms our own status as knowing subjects by reaffirming that picture as true. Things are, human beings are, and, above all, we are just as we have always supposed.”

It must now be said that — traditionally — idealism was a philosophical position on (as it’s often put) “the nature of reality”. Thus, even if poststructuralists are idealists of some kind, then their idealism may still only be a small part of their poststructuralism…

However, it can also be seen as being a large part of poststructuralism!

Indeed, linguistic idealism can be seen as being the primary source of nearly everything else in poststructuralism (as this essay will now attempt to show).

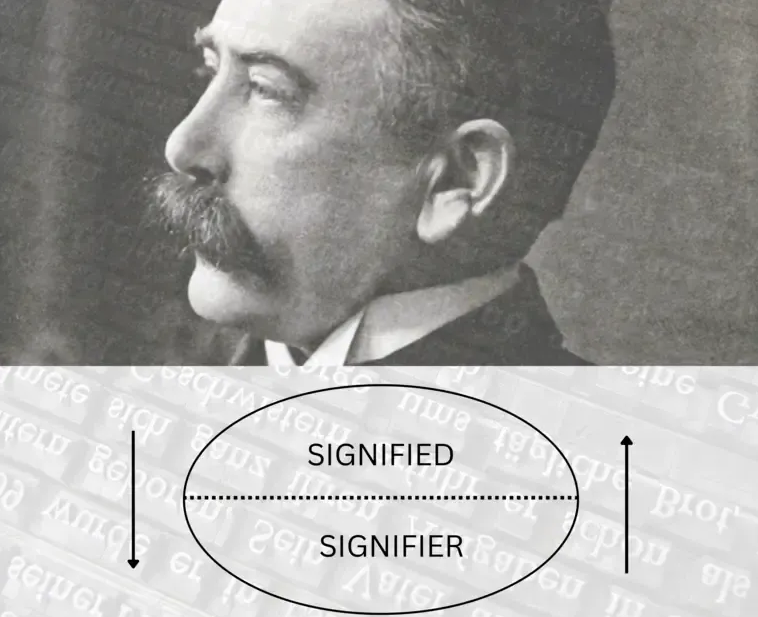

Saussure’s Linguistic Idealism?

Some readers will be aware of how important Ferdinand de Saussure was to the poststructuralists who came after him.

Yet the thing about Saussure was that he rarely discussed political, ethical or social issues. What’s more, he wasn’t a philosopher: he was a linguist. Prima facie, then, it may seem hard to directly connect him to either poststructuralists or to poststructuralism...

But don’t worry about that.

Catherine Belsey herself does the connecting for us.

Basically, Belsey shows us how important Saussure was to poststructuralists.

But, more relevantly, Saussure’s very own (possible) linguistic idealism is at the heart of this issue...

Linguistic idealism?

Well, Belsey put Saussure’s position in this way:

“Meaning, Saussure proposed, did not depend on reference to the world, or even to ideas [about the world or things].”

Belsey also told us that “[f]or him, meaning resides in the sign and nowhere else”.

On the face of it, the statement (to change the tense)

Meaning does not depend on reference

is remarkable.

Thus, some readers may wonder about Belsey’s words “did not depend on”.

What do they mean?

Few philosophers have claimed that language or “meaning” is entirely dependent on reference. (Referentialists like J.S. Mill came close to this — see here. See also ‘Direct reference theory’.) So if Belsey was arguing that, then she was arguing against her own straw target.

In any case, from Belsey’s words alone, it would be easy to conclude that Saussure believed that meaning (or language) does not depend on reference at all! Indeed, if this isn’t the (radical) thesis that Belsey was offering us, then most alternatives would be purely mundane, and not something that would be controversial.

The same questions arises for the statement “meaning resides in the sign and nowhere else”. Rather that disagreeing with it, it’s hard to understand exactly what this means.

It’s true that few — very few — philosophers have come close to arguing that meaning itself can be found in “the world” or in referents. (According to John Heil, some philosophers believed that “words are connected to things [] by ‘outgoing’ chains of significance guided by the agents’ thoughts (‘noetic rays’)”, see ‘Noetic’.)

But, again, the erasing of the world and/or reference entirely is another thing…

Unless they aren’t being erased in Belsey’s philosophical scheme.

However, if they aren’t, then her position stops being radical, and starts being (as already stated) mundane. And if it truly is mundane, then Belsey wouldn’t be writing about it. After all, lots of mundane positions that provide a (as it were) middle ground between reference (or the world) and language have been offered in the 20th century (as well as before) by people who aren’t poststructuralists (e.g., by analytic philosophers and by many others).

So surely Belsey is offering us much more than that.

In any case, Saussure’s (possible) linguistic idealism was taken further.

Take the French painter and sculptor Georges Braque (who isn’t quoted or mentioned in Belsey’s book), who once wrote:

“I do not believe in things, I believe only in their relationship.”

And now take French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan (who is quoted and mentioned in Belsey’s book), who wrote:

“It is the world of words that create the world of things [].”

Some readers may deny that this is linguistic idealism in the sense that Lacan at least acknowledged “the world of things”.

Or did he?

Well, there was nothing to stop Lacan from arguing that things are simply a product of “the world of words”. (Professor Donald Hoffman and other contemporary idealists stress that things are the product of the world of consciousness — or consciousnesses in the plural.)

Again, and as with Belsey, if Lacan simply opted for the idea that things are a factor of words, yet things aren’t themselves words, then that would have been a (fairly) mundane position. Yet Lacan wouldn’t have liked to advance any mundane position. Thus, this linguistic idealism interpretation seems feasible here.

If we return to Saussure.

Many of Saussure’s ideas can be agreed with.

For example, his stress on the (rather obvious?) relation of words to other words, the nature of linguistic “systems”, “difference”, etc. However, Catherine Belsey’s account of Saussure’s position (i.e., as one which calls for the complete erasing of reference or the world) is another thing entirely.

So perhaps Saussure and Lacan didn’t want to erase reference or the world — even if Belsey did.

Perhaps they had a more subtle take on this matter.

Is the World Created By Language?

Catherine Belsey tells her readers that “few issues are more important in human life” than language. In detail:

“[L]anguage and its symbolic analogues exercise the most crucial determinations in our social relations, our thought processes, and our understanding of who and what we are.”

This, of course, contains an element of rather obvious truth.

So it’s where Belsey went next that’s of interest.

Firstly, Belsey eases her readers in gently by simply saying that “language intervenes between human beings and the world”.

So at least the world is recognised here.

Belsey continues:

“Poststructuralism proposes that the distinctions we make are not necessarily given by the world around us, but are instead produced by the symbolizing systems we learn.”

Admittedly, Belsey plays down her own poststructuralism and the radical nature of poststructuralism in two ways in that passage.

Firstly, Belsey uses the words “are not necessarily” in order to downplay the (well) absoluteness of poststructuralism’s claim. Yet those three words are a gratuitous addition which don’t seem to play any role. That’s because there’s no not necessarily about this poststructuralist position. Poststructuralists do believe that our “symbolizing systems” (not “the world around us”) produce our “distinctions” and the world.

Secondly, Belsey writes about poststructuralism (in the passage above and elsewhere) in the (as it were) third person (as in the words “poststructuralism proposes”). However, it’s crystal clear that she was, if not an outright poststructuralist herself, then someone who was extremely positive toward poststructuralism.

The idealist idea (which Belsey herself would simply class as poststructuralism) is expressed (poetically) again in the following passage:

“Both the signifier and the image are on the same side of the glass, if glass it is. Here language is not a window onto the world.”

So if language is not a window onto the world, then surely Belsey believed this:

Language is a window onto language.

Here again, this isn’t a stress on both sides of the divide: language and world. Instead, there is the explicit statement that “language is not a window onto the world”.

So isn’t Belsey’s position a clear erasing of the world?

Alternatively (using a word that Belsey uses elsewhere), isn’t this an erasing of reference?

In more concrete and colourful terms, even wheelbarrows are deemed to be linguistic items by Belsey. As Belsey herself put it:

“On this reading, the red wheelbarrow of this poem issues from language, not from the world of things.”

Admittedly, Belsey did say (in the third person again) that this is a poststructuralist “reading” of a poem by William Carlos Williams called ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’.

Again, we have a problem with the words “this poem issues from language”.

As with all the other quoted passages from Belsey, it’s hard to know how to (well) read her words when they only hint at linguistic idealism (specifically the words “issues from”).

In one obvious sense, of course a poem written in words “issues from language”. (It issues from the words used within it.) Yet, as before, Belsey must have meant more than that. She surely meant something philosophically outré.

So, in effect, Belsey believed that this poem is exclusively about language.

(One reason Belsey gives for her idealist conclusion is that, to her, the poem ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’ doesn’t seem to be about “any real farm”.)

For if she didn’t mean that, then any other philosophical (i.e., not aesthetic and interpretive) reading of this — or any other — poem would probably be fairly mundane. However, if it were mundane, then it wouldn’t be poststructuralist. In other words, Belsey didn’t what to be taken to be simply stating the obvious.

Instead, Belsey was offering a position which can be taken to be an expression of linguistic idealism.

That said, it’s hard to understand (even from Belsey’s own reading) why it should be concluded that this poem isn’t about a wheelbarrow and other things, rather than being purely about language.

Sure, language, metaphor, analogy, interpretation, imagination, “intertextuality” (or “citationality”), etc. may well play their part in the reading of this and of all other poems. However, why conclude that this poem isn’t about “the world of things” at all?

Indeed, even Belsey’s own reading of this poem doesn’t warrant this idealist conclusion.

Conclusion: Poststructuralism’s Linguistic Idealism and Politics

It’s of course the case that at least some defenders of Catherine Belsey, and defenders of poststructuralists generally, will argue — or will they? — that the detailed arguments which justify this erasing of things and the world are offered elsewhere. (Alternatively, such people may say that there are arguments which show that there isn’t any actual erasing of things or the world in poststructuralism.)

The thing is, the arguments just aren’t offered in Belsey’s own book.

Sure, this book is only an introduction. However, I would argue that there aren’t any (or at least there aren’t many) arguments anywhere else either…

That may be explained by the fact that many poststructuralists have explicitly (well) argued against argumentation (as well as stressed “lived experience” and “radical change”, not argumentation or debate).

Finally, I just mentioned radical change in parenthesis.

Linguistic idealism is mainly a means to an end for poststructuralists. (This is certainly true of Catherine Belsey herself.)

That end is political.

Basically put, the acceptance of linguistic idealism (i.e., as found in poststructuralism) is a perfect vehicle for advancing various political causes and goals.

[Incidentally, this strongly parallels how spiritual idealists employ idealism to advance various “spiritual” causes and goals.]

Thus, for poststructuralists, linguistic idealism isn’t really (or isn’t only) a philosophical thesis which stresses the primacy of language (or “discourse”). It’s a thesis that’s been used — via the focus on language — to advance radical political change. This political interpretation of poststructuralism is, of course, strongly at odds with the critical readings of both poststructuralism and postmodernism which have been offered by many Marxists. (This will be covered in my next essay.)

So as a quick taster of what’s to come later, here are a few more lines from Belsey’s book.

Firstly, Belsey tells us that Lyotard mentioned those people who “lamented the impossibility of truth”. Lyotard, on the other hand, “rejoiced in the freedom this impossibility conferred”.

Why did Lyotard rejoice in this impossibility of truth?

Belsay continued:

“Postmodernism celebrates the capability of the signifier itself to create new forms and, indeed, new rules.”

And all that will be the subject of my next essay on Belsey’s Poststructuralism: A Very Short Introduction.

Note

From a poststructuralist perspective, this is odd. It’s odd considering Louis Althusser’s penchant for rigid ideologies, oppressive states, and his complete loyalty and obedience to a — communist — political party. (See ‘Althusser, ideology, and Stalinism: A response to Andrew Ryder’ and ‘Althusser and Stalinism’.) Still, it isn’t really a surprise that supporters of Althusser play down his Stalinism. (Some of his fans even play down his Stalinism by playing up his Maoism — see here). Still, it seems very odd — or is it? — that a poststructuralist like Catherine Belsey should not only spend so much time on Althusser, but do so in exclusively positive terms.

(*) See my next essay, ‘Linguistic Idealism as a Weapon of Poststructuralist/Postmodernist Politics’.

My flickr account and Twitter account.

No comments:

Post a Comment