“If we really want to have an intelligent, and informative, and helpful discussion, we need to make sure that we’re using terms in a well-defined way that other people understand.”

— Donald Hoffman [This passage is from a video called ‘Why clear definitions are key to intelligent discussions | Donald Hoffman’. See note 1 at the end of this essay.]

“[] when you have limited math talents like me. [] That’s what led me to then go to a real mathematician [and fellow idealist] Chetan Prakash and pursue the theorems now in the case of the agent dynamics.”

— Donald Hoffman [From a YouTube video called ‘Abstract Math of Conscious Agent Theory w/ Dr. Donald Hoffman’. See Chetan Prakash.]

Introduction

Donald Hoffman’s notion of what he calls a “conscious agent” is central to to his entire idealist philosophy.

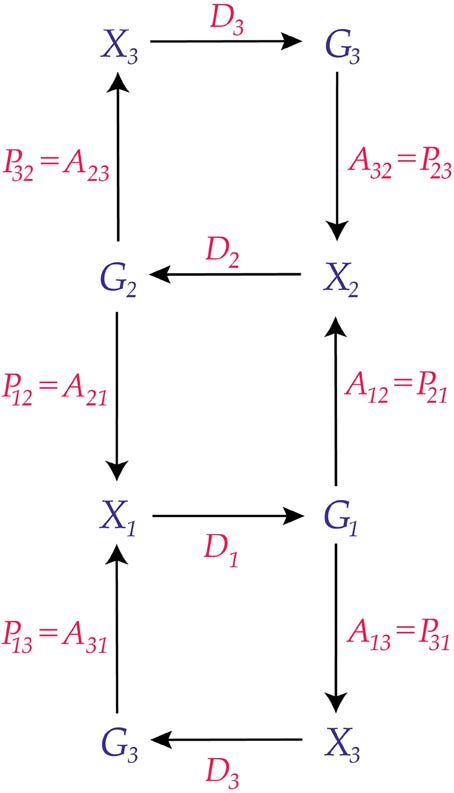

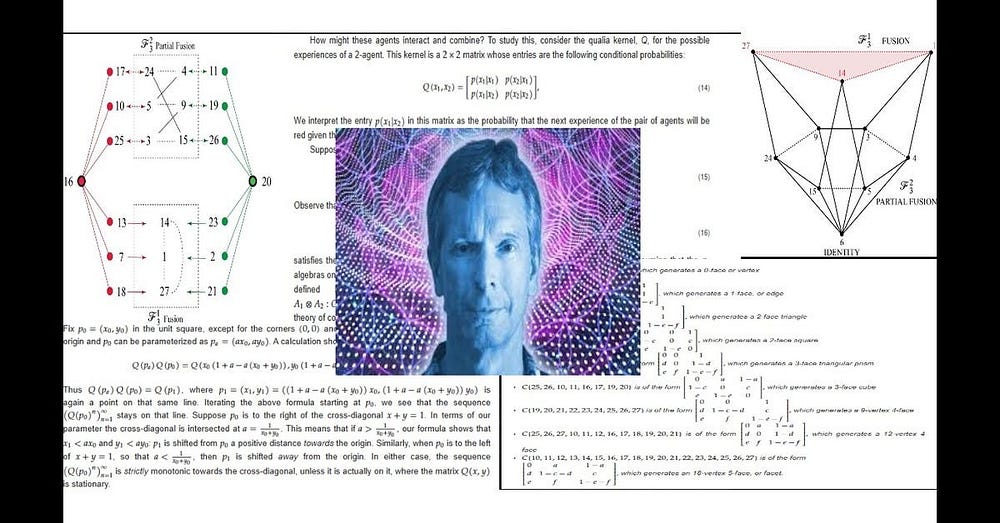

Hoffman tells his readers lots of things about conscious agents (which usually involves lots of numbers, symbols, graphs and mathematical terms). He also tells his readers what conscious agents can do. However, he doesn’t really tell them what conscious agents are.

I’ve written a few essays on Donald Hoffman. The reason I’ve done so is that although Hoffman is a best-selling writer (see The Case Against Reality), and is extensively interviewed and discussed (at least for a scientist) on YouTube, in newspaper articles, magazines, etc., he’s been virtually ignored by professional scientists and professional philosophers. [See note 2 at the end of this essay.]

In any case, after studying Hoffman’s work for a few years, I still didn’t really understand what a conscious agent is. More importantly, Hoffman never really says what a conscious agent is. He does other things instead, such as provide his readers and followers with lots of maths to explain what conscious agents do.

Even in a section called ‘Conscious Agents’ (which is part of his paper ‘The Origin of Time In Conscious Agents’), Hoffman never tells his readers what a conscious agent is. Instead, we have lots of diagrams, charts, numbers and symbols. We also read about “evolution”, “natural selection”, “Einstein”, “species-specific adaptation”, “physicalism”, “the mind-body problem”, “spacetime”, “Turing machines”, etc. In fact, everything under the sun seems to be discussed in Hoffman’s paper on conscious agents and time.

All that said, Hoffman does seem to say that a conscious agent is some kind of fundamental entity. In other words, a conscious agent is Hoffman’s philosophical equivalent of Leibniz’s monad, a particle, or something beyond — or at — the Planck length/s. Yet Hoffman also argues that he and other human persons are conscious agents too.

Of course, Hoffman might well have told his readers, fans and followers what a conscious agent is. And the fact that I haven’t personally grasped that may simply be a fact about my own personal cognitive deficiencies (i.e., dumbness).

This must mean that the American biologist Jerry Coyne is (to use his own word) “dense” too. Coyne similarly wrote:

“For the life of me I can’t figure out what the man is trying to say. [] it seems that what [Donald Hoffman is] saying should be clear. Yet what I read is either unclear, or, when it’s clear, seems wrong. [] It’s all a mess, and seems a bit like a gemisch of quantum woo, evolutionary misunderstandings, and postmodernism. If there’s a substantive and important point in the piece, I’ve been too dense to see it.”

Alternatively, Hoffman may not ever actually tell his readers and fans what a conscious agent is — at least not in simple terms. Instead, he may use mathematical and technical obfuscation to hide this fundamental flaw in his entire (seemingly mathematical) philosophy.

Oddly enough, one follower (or fan) of Hoffman does seem to understand exactly what a conscious agent is. The guy who understands Hoffman is an “entrepreneur, venture partner, inventor of the Quantum Backward Thinking” called Dr. Leon Eisen.

In an article called ‘How The Theory Of Conscious Agents Can Revolutionize Your Leadership’ (published in Forbes), Dr. Leon Eisen states the following:

“[T]he concept of conscious agents provides an exciting framework for understanding how conscious leaders can shape their teams’ perceptions. The theory states that our perceptions of the world are not just a passive reflection of reality but are actively shaped by our beliefs, values, experiences and purposes. As leaders, we have the power to influence and shape others’ perceptions by creating a culture of diversity that supports and empowers them.”

Dr Leon Eisen continues:

“[T]he theory of conscious agents suggests that our perceptions of the world are not fixed and predetermined but are actively shaped by the conscious agents’ network. By challenging the deterministic foundation of our world, conscious leaders can create a more dynamic and adaptable business environment that incorporates purpose rather than cause.”

Of course, I used the word “understand” ironically.

Yet it’s clear that Eisen believes that he understands “the concept of conscious agents”. The problem here is that Eisen doesn’t really tell us what a conscious agent is either. Perhaps more correctly, nothing in Eisen’s account distinguishes Hoffman’s term “conscious agent” from the terms “subject”, “person” and even “adult human being”. Indeed, Eisen’s account of Hoffman’s “theory” (or “concept”) of conscious agents is an embarrassing mixture of fluffy corporatese and philosophical positions which were held long before Donald Hoffman was even born.

Are Conscious Agents Primitives?

It may be the case that conscious agents are primitive, fundamental or even brute, and that would explain why Hoffman doesn’t tell us what they are… Except, again, that he says that he is a conscious agent, and that other human persons are too.

The case for primitiveness or fundamentality certainly applies to Gottfried Leibniz’s monads. And Hoffman has been strongly influenced by Leibniz’s work.

Hoffman obviously and strongly connects Leibniz’s monads to his own conscious agents.

Thus, we have these words from Hoffman:

“[I]n the system of G.W. Leibniz who proposed that simple substances (‘monads’) are the ultimate constituents of the universe and that physics, as it was known back then, would result from the dynamics of a network of such monads.”

Hoffman expands on this in the following passage:

“Our posits for the notion of a conscious agent mirror G.W. Leibniz’s posits for his notion of a simple substance: ‘there is nothing besides perceptions and their changes to be found in the simple substance. Additionally, it is in these alone that all the internal activities of the simple substance can consist’.”

In very basic terms, then, Hoffman is simply substituting the word “monad” with his own words “conscious agent”.

So now take the word “primitive” as it’s used in the following passage:

“In Hoffman’s theory, conscious agents are the primitive constituents of reality. The objective world consists of conscious agents and their experiences. [] [H]umans are just one complex type of conscious agent.”

We aren’t really told what conscious agents are in that passage either. We are told that they are “the primitive constituents of reality”. And then we’re given an example of a “complex type of conscious agent” — a human conscious agent.

I could say that blairbles and catjumps are the “primitive constituents of reality”. However, most readers may still want to know what they are.

Say that quarks and/or fields are taken to be primitive (or fundamental) in physics. Physicists can, of course, tell us a hell of a lot about both.

So what about conscious agents?

It’s no use being told that “humans are just one complex type of conscious agent” if we don’t know what a conscious agent is in the first place. Similarly, being told that the “objective world consists of conscious agents and their experiences” isn’t of much help either if we aren’t told what conscious agents are.

What’s more, we aren’t really told (at least not in the passage above) why humans are a “complex type of conscious agent”, and what accounts for that complexity. (Hoffman’s complex “maths” doesn’t do so either.)

One interesting distinction in the passage above is the one made between conscious agents and “their experiences”. (This clashes with Hoffman’s earlier quotation of Leibniz saying “there is nothing besides perceptions and their changes”.) This tells us that conscious agents are over and above their experiences. That is, conscious agents are not equal to their experiences. (They’re not identical to their experiences.) And neither are conscious agents entirely constituted by their experiences.

All this, of course, raises the same question:

What is this conscious agent which has, or which instantiates, experiences?

As it stands, this account of Hoffman’s position is actually just a bunch of categorical statements or even mere stipulations. That said, Hoffman himself does go into detail. However, when he does, he still doesn’t tell us what a conscious agent is.

For example, in his paper ‘Conscious Realism and the Mind-Body Problem’, Hoffman explains that “a conscious agent is not necessarily a person”.

That’s fair enough.

It’s true that simply because Hoffman has said that he and other human persons are conscious agents, then that doesn’t also mean that all conscious agents must be human persons.

Hoffman continues:

“All persons are conscious agents, or heterarchies of conscious agents, but not all conscious agents are persons.”

That’s it.

At least Hoffman leaves it there in this passage, and indeed in the paper this comes from.

Planck-Length Conscious Agents

On the one hand, Hoffman argues that the category of conscious agents includes himself and other human persons. On the other hand (at least according to Maciej Sitko),

“Hoffman’s take is about conscious agents all the way down to the size of binary agents (Planck length/area sizes)”.

Sitko continues:

“The world is composed of conscious agents that compose bigger and bigger agents. It might even have place for a scientific take on God, who can be an uber-agent containing all subordinate agents at once.”

As for this fusion (or combination) of “bigger and bigger” conscious agents, Hoffman himself tells us (in his paper ‘The Origin of Time in Conscious Agents’) that

“[i] happens that there are networks of conscious agents that have the computing power of universal Turing machines, and that any subset of a pseudograph of conscious agents is itself a single conscious agent”.

What does that mean?

In any case, is all this a display of Hoffman’s very own combination problem?

Thus, is Hoffman’s notion of a “fusions of consciousness” (as it were) additive in nature? In other words, is it simply that conscious agents can add (or sum) together? Alternatively, is adding different from fusing? (The similarity with panpsychism's original combination problem is obvious.)

More relevantly, can Hoffman use the same term (i.e., “conscious agent”) for something “the size of binary agent (Planck length/area sizes)” as he does for a conscious agent like Donald Hoffman himself — with his brain, legs, arms and so on? In other words, what do these Planck-length conscious agents share with a conscious agent like Donald Hoffman? In other words, what right has Hoffman to use the words “conscious”, “agent” and “conscious agent” about entities at the size of Planck lengths at all?

Perhaps one can guess here that Hoffman explains all this in terms of the (what he calls) “fusions” of Planck-length conscious agents. (See Hoffman’s paper ‘Fusions of Consciousness’.) So is it that Planck-length conscious agents fuse (or combine) together in order to create (or bring about) a Hoffman-sized conscious agent?

Added to these combination (or fusion) problems is Hoffman’s additional idea that Hoffman-sized conscious agents can also combine (or fuse) with other Hoffman-sized conscious agents…

But what on earth does all that mean?

What is the end result of all these fusions or combinations?

Is it just about the bringing forth of a “larger” conscious agent? Additionally, is it also about the (what Hoffman calls) “projections” of these larger conscious agents?

Some readers may still be completely in the dark here.

Hoffman rarely — if ever — explains any of this in scientific (physical) terms, even though he clearly sells his philosophy as being scientific. (He can’t explain it in physical terms because he’s an idealist.) Instead, he’s created his own jargon, which he embeds in (what seems to be) mathematical models. However, what is the point of such embedding if we’re never really told what these mathematical models are models of.

We get so much jargon and maths, but very little meat.

So what about reality itself?

Hoffman has had much to say about reality (such as in his book The Case Against Reality), largely from an evolutionary perspective (which shall be ignored here).

Reality and Conscious Agents

Hoffman tells us that

“reality is a vast interacting network of conscious agents, a social network like the Twitterverse”.

In the same YouTube interview, Hoffman also says that

“because reality is a bunch of conscious agents, and I’m a conscious agent, then I’m not divorced from reality”.

Hoffman uses the “is” of identity twice here — as in “reality is a vast interacting network of conscious agents” and “reality is a bunch of conscious agents”. In addition, earlier in this essay Hoffman was quoted as saying that “in the system of G.W. Leibniz [he] proposed that simple substances (‘monads’) are the ultimate constituents of the universe”. (There is an entire YouTube video called ‘Is Reality Made of Conscious Agents: Don Hoffman / Idealism’.)

Now, in this ontology, is reality actually constituted by (or “made of”) “a vast interacting network of conscious agents”? That is, is reality equal to — or identical with — this vast interacting network of conscious agents? Alternatively, is reality a product of, a result of, or (to use Hoffman’s word) a “projection” of such conscious agents?

Hoffman’s talk of “icons” and “projections” (along with his commitment to idealism itself) seems to suggest that reality can’t actually be a vast interacting network of conscious agents. The idealist message is surely that reality is somehow the product, result, or projection of a vast network of conscious agents.

Yet these two positions are very different.

So which one is it?

The distinction between a reality that is actually constituted by a vast number of conscious agents, and a reality that is projected by conscious agents, has just been mentioned.

One commentator (seemingly a fan too) of Hoffman believes that conscious agents simply “simulate consciousness”. (I’m not even sure what that means.) In his own words:

“Hoffman’s agents are a way to simulate consciousness, the conscious agent has rules of reaction when it meets another [conscious] agent.”

Isn’t that a very deflationary account of Hoffman’s philosophy?

In other words, this isn’t about ontological entities: it’s about ways of simulating consciousness. In this account at least, conscious agents are simply simulations of consciousness.

Yet doesn’t Hoffman believe that conscious agents are real ontological entities, not simulations of… anything? Indeed, aren’t these conscious agents themselves supposed to be responsible for all simulations, “icons”, objects, etc? In other words, aren’t physical objects, spacetime, brains, neurons, etc. merely the icons of conscious agents?

Thus, in Hoffman’s (idealist) philosophy, conscious agents aren’t the simulations of consciousness: they are the very ground and source of reality.

Notes

(1) I’m guessing that what Donald Hoffman means by “using terms in a well-defined way” is using an often impenetrable prose, which incudes lots and lots of mathematical terms, scientific jargon, graphs, numbers and symbols.

I, for one, will happily admit that most of the time I don’t “understand” what Hoffman is saying (just like Coyne). The odd thing is that, in the many interviews of Hoffman I’ve seen (there are literally dozens on YouTube — see here), those who interview him don’t seem to understand him either. Instead, they’re either starstruck by his jargon (many interviewers look like they’re in awe of the man), or they ask him to elaborate upon (i.e., they don’t question or criticise) what he’s just said, which he does with yet more jargon.

Very rarely — almost never — do his interviewers criticise or even question what Hoffman states with so much confidence. (The philosophers Philip Goff and Keith Frankish come close to being critical of Hoffman’s ideas — or his jargon — in a YouTube video called ‘What is Reality?’.)

(2) This isn’t the case when it comes to Donald Hoffman’s work which falls purely within the domain of cognitive science. So it can safely be assumed that other professional scientists have indeed read and tackled Hoffman’s (purely) cognitive-science work.

Incidentally, Donald Hoffman’s fellow spiritual idealist, Bernardo Kastrup, takes this situation of professional scientists and professional philosophers almost completely ignoring his work as proof that he’s onto something profound and deep. In that sense, then, Kastrup clearly sees himself as a scientific and philosophical “heretic”, just as the English author and parapsychology researcher Rupert Sheldrake also does. (See Sheldrake the heretic here.) Relevantly, Kastrup classes nearly all scientists and philosophers (i.e., outside his spiritual idealism) as “materialists”. Thus, as a spiritual idealist, Kastrup can’t help but be an heroic heretic.

In his post ‘Reason or covetousness? On academic philosophy’, Kastrup also conflates professional scientists and professional philosophers taking his work seriously with the fact that he has indeed “engaged” with some professionals, and also been “invited to debate well-known philosophers”. In his own words:

“[T]he fact that well-known academic philosophers — such as David Chalmers — have cited my work in print, or that others — such as Philip Goff — have gone out of their way to engage me multiple times in public, or that yet other academics — such as Keith Frankish and Michael Graziano — have had heated exchanges with me also in print, or that I’ve been invited to debate well-known philosophers and public intellectuals.”

All sorts of irrelevant people are cited in print. (Has Kastrup’s idealist philosophy ever been the main or sole subject of these citations in print?) In addition, Kastrup has a cult following. Thus, those people who arrange and produce popular-science and popular-philosophy debates are highly likely to invite Kastrup, who offers the general public a spiritual, sexy and titillating philosophy. And that must surely at least partly explain why some of the names Kastrup mentions have felt the need to “engage” with him. In their papers and books, on the other hand, they almost completely ignore him. (I would like to see how David Chalmers cites his work.) Of course, it’s possible that some of the people Kastrup names do indeed rate him. However, I’d bet money that they don’t.

*) See my related essay, ‘Donald Hoffman’s Mathematical Models of Conscious Agents’.

(*) My other essays on Donald Hoffman: ‘Donald Hoffman’s Philosophy of Consciousness and Reality: Conscious Realism’, ‘A Contradiction in Donald Hoffman’s (Idealist) Fitness-Beats-Truth Theorem’, ‘Professor Donald Hoffman’s Idealist Take on Brains and Volleyballs’, ‘Professor Donald Hoffman’s Mathematical Models are Eye Candy’, and ‘Donald Hoffman’s Case For An Idealist and Spiritual Reality’.

My flickr account and Twitter account.

No comments:

Post a Comment