In Rupert Sheldrake’s book, The Rebirth of Nature: The Greening of Science and God, there’s a passage about science and scientists which encapsulates Sheldrake’s own serious problems with both. It’s also, it will be argued, full of caricatures and gross exaggerations.

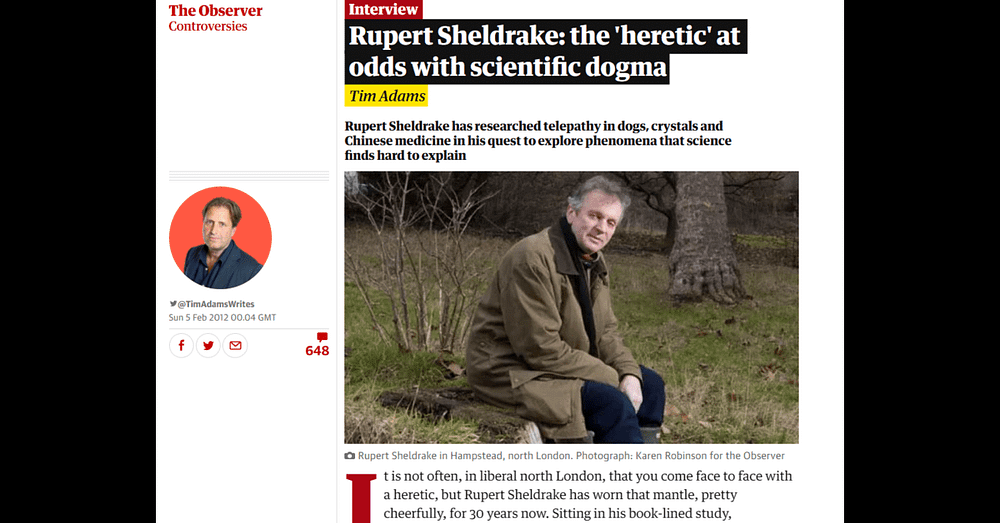

Alfred Rupert Sheldrake (who was born in 1942) is a very controversial figure.

He’s an English author and parapsychology researcher. Sheldrake is now primarily known (at least in scientific circles) for his “conjecture” of morphic resonance, which has been strongly criticised by scientists and by many others. Indeed, it’s often been classed as mere pseudoscience.

Yet Sheldrake is indeed a scientist.

He’s worked as a biochemist at Cambridge University, been a Harvard scholar, a researcher at the Royal Society, and a plant physiologist.

Sheldrake has also done work on precognition, telepathy, and the psychic staring effect. Consequently, he’s been described as a “New Age” theorist.

Now for a few words on Rupert Sheldrake’s book The Rebirth of Nature.

The Rebirth of Nature is interesting. It’s very well written, easy to understand, and, oddly enough (at least to me), not in the least bit pretentious. (This is in marked contrast to other books written by people who’ve similar views to Sheldrake.) It’s also very interesting in terms of its neat little histories, as well as its informative capsule-form accounts of various aspects of science.

Where this book is controversial is in its philosophical additions. It’s also problematic because of its large use of bizarre analogies (see note 3), as well as its free and easy — often postmodern - interpretations of religion and history.

[Sheldrake relies on “postmodern theologians”, etc. for some of his views. See note 1.)

More broadly, it may be useful to place the passage focussed upon in this essay within the context of Sheldrake seeing himself as a scientific “heretic”.

To be fair to Sheldrake, that word was originally used (very critically) about Sheldrake by someone else. However, it’s safe to say that Sheldrake has now clearly and happily adopted this designation for himself. (See here.)

The word “heretic” was used by the theoretical chemist, physicist and science writer John Royden Maddox in response to Sheldrake’s book A New Science of Life, which was published in 1981. Maddox’s 1981 editorial (in Nature) is called ‘A book for burning?’.

Now clearly the word “heretic” and the title “A Book for burning?” are well over the top. That said, Maddox did conclude that the book should not be burned.

[Maddox’s piece also appears to have been part of a series called ‘A book for burning’. See more information in note 2.]

Yet I still have serious problems with Maddox’s rather intemperate and authoritarian remarks.

For example, Maddox later said (in 1994, some 13 years later) that he still thought that

“it is dangerous that people should be allowed by our liberal societies to put that kind of nonsense into currency”.

This is outrageous stuff.

It’s not the use of words like “nonsense”, “pseudoscience”, etc. that I have a problem with. (See some examples of Sheldrake’s bizarre statements in note 3.) It’s the highly-objectionable words “it’s dangerous that people should be allowed by our liberal societies to put that kind of nonsense into currency”.

No wonder Sheldrake has such a negative attitude toward science and scientists with people like John Maddox shouting at him. However, this is all that’ll be said on the Maddox-Sheldrake controversy here.

In any case, in this essay I shall break the aforementioned passage from Sheldrake down, and tackle each part separately.

But, firstly, it’s worth stating it in full:

“To this day, scientists pretend that they are rather like disembodied minds. Unlike other human activities, science is supposed to be uniquely objective. Scientific papers are conventionally written in an impersonal style, seemingly devoid of emotions. Conclusions are meant to follow from facts by a logical process of reasoning, such as that which might be followed by a computer, if machines with sufficient artificial intelligence could ever be constructed. Nobody is ever seen doing anything, methods are followed, phenomena observed, and measurements are made, preferably with instruments. Everything is reported in the passive voice. Even schoolchildren learn this style, and practise it in their laboratory notebooks: ‘a test tube was taken…’

“All research scientists know that this process is artificial; they are not disembodied minds, uninfluenced by emotion.”

Do Scientists Believe They Have Disembodied Minds?

“To this day, scientists pretend that they are rather like disembodied minds.”

No scientists I’ve ever read or come across has pretended that he/she is a disembodied mind. (Obviously, this is a partly anecdotal view.) So readers can guess that what Rupert Sheldrake must have meant is that this is the implicit (or subconscious) position of (all? most? many?) scientists. Alternatively, this supposed pretence is a consequence of what scientists do explicitly (or actually) believe and say…

Still, there’s still no direct (or literal) pretence from scientists that they’re “like disembodied minds”.

Many scientists (as it were) get around all this with the distinction they make between science itself and (flesh and blood) scientists. However, some critics of science and postmodern philosophers have argued that this distinction is a fake — largely because they see it as an idealisation.

Philosophers attempt a similar job with their own distinction between the context of discovery and the context of justification.

It can be suspected that Rupert Sheldrake will be aware of these two distinctions. However, it can also be assumed that he doesn’t really buy them — at least not unquestioningly.

In other words, is this simply Sheldrake’s interpretation of what scientists believe? Indeed, even if (most? many? some?) scientists do believe that they have a monopoly on what people call “the objective facts”, then that still wouldn’t entail a commitment to believing that their minds need to be disembodied in order to access those objective facts.

What’s more, if the minds of scientists were truly disembodied, then gaining access to data, facts, experimental results, etc. would be a very tricky business indeed.

Perhaps, then, it’s pure rhetoric (or poetry) to argue that scientists “pretend that they are disembodied minds”.

Sheldrake continued:

“All research scientists know that this process is artificial; they are not disembodied minds, uninfluenced by emotion.”

Some readers can partially agree with Sheldrake here. In other words, there is indeed a certain degree of artificiality involved in academic writings and in science generally.

And that’s a good thing… Or at least it is in specified cases.

Thus, it’s not that scientists “pretend”: it’s that this artificiality is productive and it makes sense. In other words, it just wouldn’t benefit anyone to read feelings and emotions displayed in papers, etc. Sure, it may benefit a psychoanalyst, psychological researcher, people like Sheldrake, or someone who just wants to wallow in other people’s feelings. However, what point would it serve in scientific papers?

Moreover, outside science, emotions and feelings are expressed all the time, and often in an extreme manner. This is certainly the case in the domains of religion, politics, art, etc.

Is that a good thing?

Indeed, even if the expression of one’s feelings and emotions is a good thing in politics, religion and art, would it (automatically) be a good thing in science too?

Sheldrake then tackled the very specific case of what he called “scientific papers”. He wrote:

“Scientific papers are conventionally written in an impersonal style, seemingly devoid of emotions. [] Everything is reported in the passive voice.”

[See the non-ironic article ‘Academic writing tips: How to use Active and Passive voice’.]

Isn’t this true of nearly all academic work?

Isn’t it the case that almost all academic papers and academic books are “written in an impersonal style, seemingly devoid of emotions”?

And isn’t that the case for many (or at least some) good reasons?

Would it be a fruitful or a good thing that “emotions” or feelings were fully displayed in scientific papers?

This may depend on how much emotion Sheldrake believes should be displayed by scientists. A lot of emotion? Just a bit? About as much as Sheldrake himself displays in these passages, and in the rest of his book?

Indeed, would it benefit anyone to parade and express their feelings in response to other people parading and expressing their own feelings?

What’s more, what, exactly, is the alternative to this “impersonal style”, and would it be a good thing to adopt it in scientific papers?

Sheldrake then had more to say on the scientific style:

“Even schoolchildren learn this style, and practise it in their laboratory notebooks: ‘a test tube was taken…’.”

So would Sheldrake prefer the following? -

I erotically placed the sample into a beatific test tube. This event in my life filled me with wonder. And, all the while, I simply knew that doing this would advance my own career, as well as change our deeply corrupted mechanistic society.

This isn’t to deny that there is such a thing as academese. Indeed, I myself have problems with it. (See my essay ‘Why (Many) Analytic Philosophy Papers are Pretentious and Hard to Read’.) However, some readers may still wonder what Sheldrake would want to put in its place.

Perhaps Sheldrake doesn’t want to put anything in its place.

Perhaps what he says is purely descriptive. Indeed, to some degree at least, it is.

Sheldrake on Scientists’ Naive Philosophy of Science

“Conclusions are meant to follow from facts by a logical process of reasoning, such as that which might be followed by a computer, if machines with sufficient artificial intelligence could ever be constructed.”

This passage is Sheldrake’s caricature. It’s what he believes (all? most? many?) scientists take science to be.

It needn't be denied here that at least some defenders of science have put it in his way — or in similar ways. However, they too would be using caricatures. (Many of these positive — but naïve — caricatures of science don’t come from actual scientists.) However, I just don’t believe that most — or even many — scientists think in this simplistic way.

Technically, I doubt that many scientists would use a phrase like “follow from facts”. Perhaps they may say “follow from the data”, “follow from the evidence”, or even “follow from the experiments”. However, the word “fact” isn’t a scientific technical term. It’s more often used by philosophers or, more relevantly, laypeople. (There have been many definitions of “fact” which philosophers have offered us.)

What’s more, many scientists acknowledge that before any “logical process of reasoning”, the (to use Sheldrake’s other word again) “facts” too have (as it were) come about because of theory and prior processes of logical reasoning.

In any case, if scientists really believed that science were just another form of deductive logic (“such as that which might be followed by a computer, if machines with sufficient artificial intelligence could ever be constructed”), then what would be the point of the tests, falsifications, verifications, etc. of their theories? Indeed, what role would experiments play in science?

Again, if everything in science simply followed from the facts in a logical way, then science would be a purely deductive system.

Yet hardly any scientists have thought of science in these terms.

So is this simply Sheldrake’s caricature?

Here’s more from Sheldrake on the idea that scientists implicitly or explicitly see science as (some kind of) deductive system:

“Nobody is ever seen doing anything, methods are followed, phenomena observed, and measurements are made, preferably with instruments.”

Sure “methods are followed” in science. However, that’s methods in the plural. And the methods which are followed are often questioned, and even, at times, entirely rejected.

To be fair to Sheldrake, he did concede that “phenomena [are] observed”. So readers can suppose that in a purely deductive system phenomena and observation would play no role. Still, Sheldrake almost implies that “scientists” believe that phenomena are essentially the given (see ‘myth of the given’), and once they’re given, then the deductive process can begin. However, and as already stated, most scientists don’t believe that phenomena (or facts) are simply given. Not only that: they don’t see what follows as being a purely deductive process either.

As for Sheldrake’s words “measurements are made, preferably with instruments”.

It’s as if Sheldrake is implying that scientists believe that science has no role for theory. (This is, basically, a Baconian/17th century position on science.) This is astonishing because the word “theory” is used all the time in science, and not only in theoretical physics and theoretical biology — in all the sciences.

Again, this actually seems like a layperson’s view of science, not a scientist’s view of science.

And it certainly isn’t the view of science of Sheldrake’s pluralised “scientists”.

So since Sheldrake’s take on what scientists believe is such a caricature, then perhaps (again) he’s really talking about what laypeople believe about science. However, in the context of his strong criticisms of science and scientists generally, this can’t be the case.

Notes

(1) Rupert Sheldrake seems to have relied a fair amount on the American “postmodern theologian” David Ray Griffin. (Three of Griffin’s books appear in the bibliography.)

Griffin himself attempted to build a bridge between what he called modernity and postmodernity. He offered his readers — and others - “postmodern proposals” to solve the conflicts between religion and science. And, in 1983, Griffin established the Center for a Postmodern World and also became editor of the SUNY Series in Constructive Postmodern Philosophy.

More relevantly, just like Sheldrake, Griffin had many negative things to say about what he called “mechanistic science”. Indeed, Griffin’s book The Reenchantment of Science: Postmodern Proposals (1988) even has a title which is very similar to a couple of Sheldrake’s own books, including the 1990 publication focussed upon in this essay (i.e., The Rebirth of Nature).

(2) ‘A book for burning’ wasn’t even John Maddox’s own title! (See Martin Gardner’s ‘A book for burning’ in which he tackles Spontaneous Human Combustion, by Jenny Randles and Peter Hough.) What’s more, Maddox’s editorial on Sheldrake is only four paragraphs long.

(3) Quotes from Sheldrake’s The Rebirth of Nature:

“Everywhere we look in the realm of nature we find polarities, such as electrical and magnetic polarities. These can, if we like, be modelled in terms of gender [].”

“If the fields and energy of nature are aspects of the Word and Spirit of God [].”

“[] even crystals, molecules and atoms are organisms.”

“Mythic, animistic and religious ways of thinking can no longer be kept at bay. Nothing less than a revolution is at hand.”

“ [T]he fields of modern physics play many of the same roles as souls in animistic, pre-mechanistic philosophies of nature.”

My flickr account and Twitter account.

No comments:

Post a Comment