In my first essay on Catherine Belsey and linguistic idealism (‘Poststructuralism and Deconstruction as Forms of (Linguistic) Idealism’), I focused on purely philosophical matters. In the second essay (‘Linguistic Idealism as a Weapon of Poststructuralist/Postmodernist Politics’), the theme is explicit in the title itself. This final essay is similar to the second, except that it focusses on various Marxist critiques of poststructuralism and postmodern philosophy, as well on how Marxists have also tied these two isms to linguistic idealism.

In simple and perhaps crude terms, poststructuralists and postmodernists believe that politics is all about the words (or “discourses”) we use. Of course, these are simple terms that poststructuralists and postmodern philosophers themselves would never actually use.

To cut the story short. This means that poststructuralists and postmodern philosophers believe (or believed) that (radical) political change is mainly (sometimes exclusively) about changing the words we use.

Put that way, it can be strongly suspected (again) that poststructuralists and postmodern philosophers (or their defenders) would respond by saying that things ain’t that simple.

They never are.

In any case, as the literary critic, academic and poststructuralist Catherine Belsey herself put it:

“If language, in other words, transmits the knowledges [note the plural] and values that constitutes a culture, it follows that the existing meanings are not ours to command.”

So if poststructuralists (like Belsey) want to change the “knowledges and values” of our culture and society, then they must also change our “meanings” and our words. More specifically, academics need to become the new (to use a word Belsey uses elsewhere) “Master”, and then create and “command” a new lexicon. In other words, poststructuralist academics must either change the meanings of what Belsey calls “old words”, or create new words with new meanings. And, after all that, they hope that their radical semantic changes will filter down to those outside the Academy…

These radical semantic changes have filtered down.

In Belsey’s own words:

“If meanings are not given or guaranteed, but lived all the same, it follows that they can be challenged and changed. [] If meaning is a matter of social convention, it concerns and involves all of us.”

“Postmodernism celebrates the capability of the signifier [basically, word or term] itself to create new forms and, indeed, new rules.”

All this should be familiar to most readers.

For the last decade or even less (especially in the last couple of years), there have been all sorts of new words to grasp (as well as old words being used in new ways) in politics and on social media. (To some degree, that has always been the case.)

So do these new (poststructuralist and postmodernist) words, or do these old words with new (poststructuralist and postmodernist) meanings, refer to things?

Belsey and other poststructuralists don’t believe that they need to.

Are they about the world?

There is no ̶w̶o̶r̶l̶d̶ outside the text.

[Jacques Derrida, who’s the main man behind Belsey’s own poststructuralism, once wrote: “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte.” This is usually translated as the following: “There is nothing outside the text.” See note 1.]

Thus, poststructuralists and postmodernists are linguistic idealists.

More relevantly, linguistic idealism was chosen (as a philosophical position) primarily because it serves various political causes and goals.

Marxist Critiques of Poststructuralism and Postmodernism

The main theme of this essay (as with the last one) is the politics of poststructuralism and postmodernism. Indeed, it’s the politics of postmodernism and poststructuralism (or the lack thereof!) which is (or which was) very problematic to many Marxists.

To name names.

Marxist writers such a Christopher Norris, Frederic Jameson and (the Socialist Workers Party’s) Alex Callinicos have been particularly critical of postmodern philosophers.

So, firstly, take the critical theorist and Marxist Douglas Kellner, who wrote the following in his book Jean Baudrillard: From Marxism to Postmodernism and Beyond:

“I am not sure that we have now transcended and left behind modernity, class politics, labour and production, imperialism, fascism and the other phenomena described by classical and neo-Marxism.”

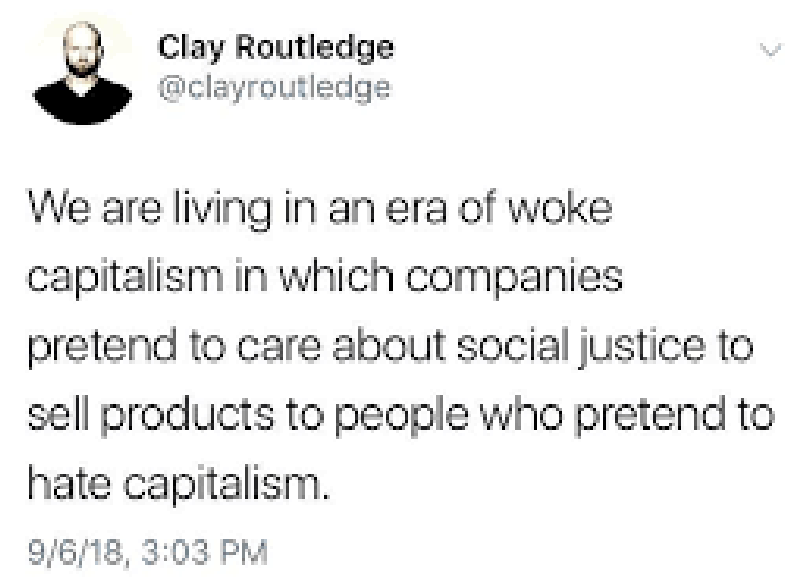

The Marxist and literary critic Fredric Jameson went even further when he argued that the whole of poststructuralism and postmodernism simply expressed “the logic of late capitalism”. [See note 2 on “woke capitalism”.]

More relevantly, Marxists have often argued that the political impotence of both poststructuralism and postmodernism is a direct result of their linguistic idealism. (It must be said that Marxists don’t always use the precise term “linguistic idealism” when discussing these issues.)

More broadly, many Marxists have claimed that poststructuralism isn’t political at all.

Or, at the very least, Marxists have claimed that it isn’t political in the right way.

As a writer in Revolutionary Publications has put it:

“[Linguistic] idealism in the garb of radicalism wants us to live within the prison-world of language.”

In other words, poststructuralism and postmodernism only have a glossy veneer of radicalism. Yes — the politics (or radicalism) of poststructuralism and postmodernism is merely a simulacrum.

This is something which has been stressed by many other Marxists.

Yet poststructuralism and postmodernism clearly are political.

Indeed, the embrace of linguistic idealism was an important way in which poststructuralists (like Belsey) and postmodern philosophers (like Lyotard) could advance their own political causes and goals.

Language as Substructure

So now take the following words from an article called ‘The Linguistic Idealism of Poststructuralism/Postmodernism’:

“This [kind of] idealism has turned language into an all-pervasive force both — sovereign and dominant, virtually diminishing human agency. Everything is discourse [] and discourse is everything.”

What’s more:

“[Linguistic] idealism preaches [about] our imprisonment within language.”

It can be argued that poststructuralists and postmodern philosophers have believed — and sometimes stated — that human persons are simply the passive subjects of language. What’s more (at least as Marxists have expressed things), poststructuralists and postmodernists have made language the substructure (even if not deemed to be the material substructure) of politics and society as a whole.

As the just quoted article in Revolutionary Publications puts it:

“The ‘sign’ is posed as if something material, the only reality, and thus [poststructuralists and postmodernists] can discard all notions of social reality.”

What’s more, there is even (do I need to write “even”?) a Marxist defence of objective truth in the following passage:

“With the departure of objective things [] there cannot be any fundamental role for [] truth as a correspondence between the domain of objective things and the subjective idea.”

Is that a misrepresentation of poststructuralism and postmodern philosophy?

Well, French sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard — for one — once wrote that “[r]eality itself is too obvious to be true”, and that “truth does not exist”.

The English literary theorist, critic and Marxist Terry Eagleton put a similar point about postmodernism when he summed up its philosophy as the position that there

“is in truth nothing there to be reflected, no reality which is not itself already image, spectacle, simulacrum, gratuitous fiction”.

Ironically (or perhaps not), Baudrillard agreed with Eagleton’s account. At least he did so in the following passage:

“Postmodernity is [] a culture of fragmentary sensations, eclectic nostalgia, disposable simulacra, and promiscuous superficiality, in which the traditionally valued qualities of depth, coherence, meaning, originality, and authenticity are evacuated or dissolved amid the random swirl of empty signals.”

The following point is important to Marxists — as it is to many others.

If there is “no reality”, and everything is “image, spectacle, simulacrum, gratuitous fiction”, then what grounds do poststructuralists and postmodernists have for political action? (At the very least, how would they argue their political case?)

Thus, is it simply a case of language games (or Lyotard’s phrase regimes) against language games? (Remember, “language game” is a term that Catherine Belsey herself uses — see here.)

Of course, not only Marxists have made these points against postmodern philosophy and poststructuralism.

Noam Chomsky on Postmodern Philosophy

Take this small selection of Noam Chomsky’s words on both postmodern philosophy and postmodern philosophers:

“pseudo-scientific posturing”, “cults”, “obscurantism”, “trivial”, “complicated verbiage”, “the mutual-admiration societies of intellectuals”, “crazy ideas”, “incomprehensible rhetoric”, “incoherent sentences”, “inflated rhetoric”, “self- and mutual-admiration”, “meaningless”, “irrational”…

In terms of philosophical detail, Chomsky fills in some detail here:

“One of the ways to have exciting new ideas is to tear everything to shreds, and say ‘everything was wrong’. You know, the ‘Enlightenment was wrong’. There’s ‘no foundationalism’. That’s right, there’s no foundationalism. [and] that was known in the 17th century. But they had to rediscover it, and put it in a fancy way. [] Well out of this comes this irrational tendency.”

As with the Marxists just discussed, it was the political consequences of all this “complicated verbiage”, etc. which concerned Chomsky.

He continued by saying that all this “did undermine dedicated activism”. More concretely, Chomsky recalled the time (in this YouTube video) when a student asked the following “rather plaintive question”:

“‘Bertrand Russell tells us we should look for the truth, but the philosophers tell us there is no truth. So what should we do?’”

Chomsky also said that a political theory should be — or at least it must become — “well tested and verified”. That is, a theory should

“appl[y] to the conduct of foreign affairs or the resolution of domestic or international conflict, rather than simply remain as pseudo-scientific posturing”.

What’s more, the “little” parts of postmodernism which are

“sometimes quite interesting [still] lack [ ] consequences for the real world problems that occupy my time and energies”.

Chomsky’s criticisms almost perfectly harmonise with some Marxist critiques of postmodern philosophy (this isn’t to say that Chomsky is a Marxist himself), such as those found in Terry Eagleton’s book The Illusions of Postmodernism, Alex Callinicos’s book Against Postmodernism: A Marxist Critique, and Fredric Jameson’s book Postmodernism: or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.

Now take the analytic philosopher Ian Hacking and the very title of his book, The Social Construction of What?

… Sure, Hacking uses the words “social construction”, not linguistic construction. However, we can just as easily ask the following questions:

Language games about what?

Words and terms about what?

“Discourse” about what?

… But hang on a minute!

Catherine Belsey has already told us (as stated in the first essay) that words are about words. This also means that discourse is about discourse.

More broadly, whatever is said or written in a language game will be about other things which are written and said within that language game.

Thus, in poststructuralism and postmodernism, the world and reference are erased.

This effectively means that we now have linguistic idealism as a weapon to advance various political causes and goals.

In response, Marxists say either that poststructuralism and postmodern philosophy aren’t political at all, or that the adoption of linguistic idealism doesn’t (or can’t) work to bring about (real) radical political change.

Readers can decide if Marxists are right about this.

Notes

(1) See ‘Deconstructing Systems — There is Nothing Outside the Text’, in which the writer says that this phrase isn’t idealist. He then (if implicitly!) says that it is. Harish tells us that “you can no longer appeal to reality as a refuge independent of language”. That was after quoting Alex Callinicos (mentioned in the essay above) saying that “Derrida wasn’t, like some ultra-idealist, reducing everything to language”.

Of course, any mention (or “appeal to”) “reality” will include “language”. Does that mean that reality isn’t “independent of language”? What we say about reality can’t be independent of language — by definition! But surely that wasn’t Derrida’s point because it’s a statement of the obvious.

Few contemporary realists have argued that we (well) intuit reality without the need for language. At the same time, Derrida surely couldn’t have believed that the world and things are literally made up of words or language.

Perhaps one alternative reading is that Derrida’s position is, in actual fact, commonplace. It’s a (to use Hugh Mellor’s words) “trivial truism” dressed up in arcane prose.

What’s more, almost every other explanation (or interpretation) I’ve read of Derrida’s words “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” is different — sometimes radically different. So no wonder many people have taken the translation (or the original French) literally. (Not everyone wants to “play with the sign”.)

To be honest, I don’t really understand much in Harish’s essay either. It doesn’t help that he never quotes Derrida himself. (He does quote the famous words: “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte.”) However, he quotes other philosophers attempting to make sense of Derrida.

Thus, Harish’s essay itself must also be purely (or merely?) a reading of Derrida. After all, readings are all we have. And that’s according to these very same philosophers. Indeed, Harish himself makes that point (I think!) in his essay…

Okay. I read Derrida as being a linguistic idealist.

(2) A few Marxists and people on the Radical Left are making these points today against such a thing as “woke capitalism” However, the just-linked Wikipedia article makes it seem as if only (what it calls) “conservatives” and those on the “American right” believe that there’s such a thing as woke capitalism.

My flickr account and Twitter account.

No comments:

Post a Comment