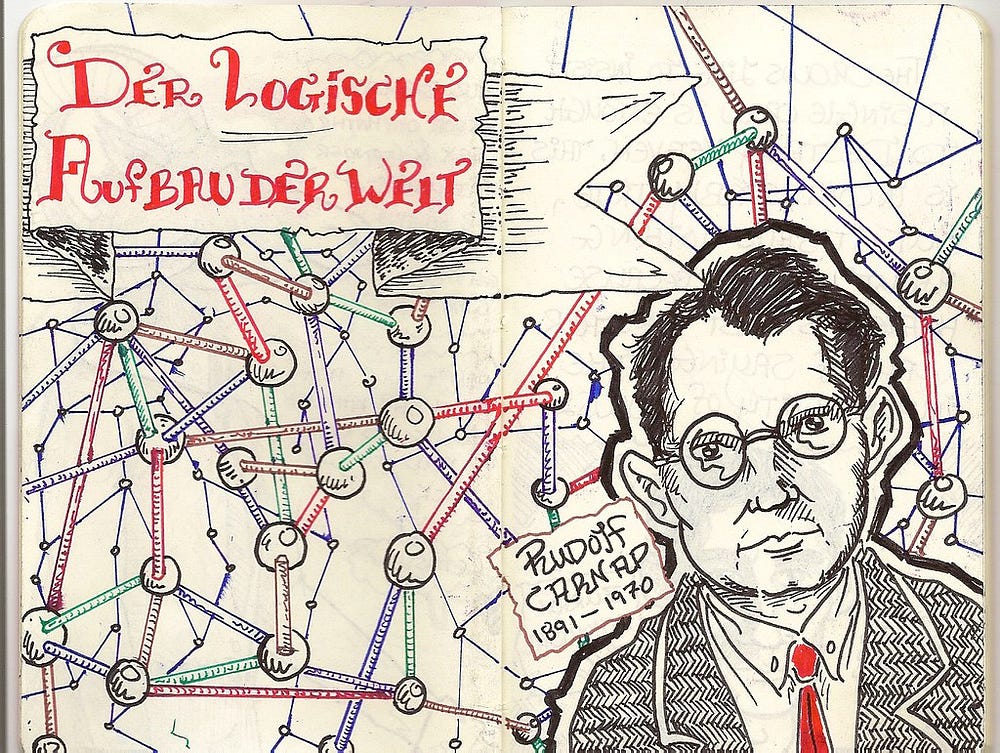

The logical positivist Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970) deemed science’s domain to be unlimited. His position perfectly captures what critics later called scientism. So it must be said that the term “scientism” is often used as little more than a term of abuse… This essay asks questions about science’s domain. It’s also about whether or not many non-scientific questions (at least the debated ones) can ever be answered. In other words, are many religious, philosophical, aesthetic, ethical, etc. questions unanswerable? Alternatively, are my own questions about questions an implicit (perhaps explicit) reversion to (some new kind of) logical positivism?

“When we say that scientific knowledge is unlimited, we mean ‘there is no question whose answer is in principle unattainable by science.’”

— Rudolf Carnap

Many people are shocked by the position advanced by Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970) above. Or at least they’re shocked by similar positions expressed by other philosophers and scientists.

Some philosophers are shocked too.

William P. Alston, for example, wrote (in his paper ‘Yes, Virginia, There is a Real World’) that it was “a piece of outrageous imperialism” to believe (or claim) that scientific knowledge is the only kind of knowledge, or that only the sciences can answer certain relevant questions.

On the other hand, many other people will strongly support Carnap’s position (at least in various qualified ways).

In any case, the opening passage perfectly captures the (or a) logical-positivist position (see ‘Logical positivism’) as it was expressed in the late 1920s. (This was published in Carnap’s 1928 book Der logische Aufbau der Welt — The Logical Structure of the World.)

Carnap’s words also perfectly capture what people now take to be scientism.

When Rudolf Carnap’s words above are quoted, they’re done so almost exclusively in relation to what the authors call “scientism”. Consequently, these words have been quoted many times (see here.) For example, you’ll find them in the book Scientism: Science, Ethics and Religion, as well as in Science Unlimited?: The Challenges of Scientism. (It can be suspected that these authors found this passage from Carnap in the writings of other critics of scientism, not from Carnap’s own book, The Logical Structure of the World.)

So it’s a little odd that these new(ish) books are relying on a passage from 1928 to summarise the (or a) scientistic position. (See the last section of this essay for some more very-retrospective bashing of logical positivism.)

Science Unlimited?

To sum up this essay’s particular take on Rudolf Carnap’s words.

The opening passage states that scientific knowledge is “unlimited”. Indeed, Carnap’s definition (“there is no question whose answer is in principle unattainable by science”) is an explicit reference to science’s unlimited (or unrestricted) role. In other words, there is “no question” (or subject or issue) which is beyond science.

This is where Carnap’s position must be both qualified and explained a little.

There are indeed some (even many) questions which cannot be answered by the sciences. However, that’s because they are — perhaps sometimes (almost) by definition — unanswerable.

In other words, no answers outside the sciences can ever be confirmed, tested, verified, quantified, etc. Consequently, they’re never conclusive. Indeed, it’s that lack of conclusiveness which takes such questions (or even their answers) beyond science.

Now some critics of scientism may freely acknowledge this. That is, they may admit that (some of) the questions which the sciences can’t answer aren’t unanswerable by any other discipline either…

However, that isn’t usually the case.

Many people believe that their own chosen religion, philosophy, or theory can indeed answer such questions. It’s just that the sciences can’t.

So can we ever know that an answer has been provided by religion, philosophy, etc?

History has often shown us that this isn’t the case.

Thus, the questions which are answered by non-scientific domains aren’t really answered by them at all. They remain in perpetual dispute.

Such is the case with most — even all — religious, philosophical, political, aesthetic, etc. answers to those questions which aren’t — or which can’t be — tackled by the sciences.

All that said, this isn’t simply a scientific take on (possibly) unanswerable questions. There are many other ways to approach this issue.

Take the American-English philosopher Gordon Park Baker (1938–2002).

In his ‘φιλοσοφια: εικων και ειδος’ (which can be found in Philosophy in Britain Today), Baker wrote:

“We should [] make serious efforts at raising questions about the questions commonly viewed as being genuinely philosophical. Perhaps the proper answers to such questions are often, even if not always, further questions!”

All sorts of questions have been deemed to be profound, deep and worthy of serious thought. These questions are usually also deemed to be “beyond science”. So perhaps it’s just as important — and indeed just as philosophical — to ask questions about these questions. Or as Gordon Baker put it:

“The unexamined question is not worth answering.”

Baker added:

“To accept a question as making good sense and embark on building a philosophical theory to answer it is already to make the decisive step in the whole investigation.”

Note that those words aren’t the views of a scientist.

They aren’t part of science either.

Relevantly, Gordon Baker’s positions certainly aren’t “scientistic”.

So perhaps these particular questions about questions are partly Wittgensteinian in nature. Indeed, Baker makes more Wittgensteinian points in the following passage:

“[T]o suppose that the answers to philosophical questions await discovery is to presuppose that the questions themselves make sense and stand in need of answers (not already available). Why should this not be a fit subject for philosophical scrutiny?”

Carnap and other logical positivists (i.e., well before Gordon Baker) did believe that these non-scientific questions were a fit subject for philosophical scrutiny. And, since then, such questions have been scrutinised by other philosophers too.

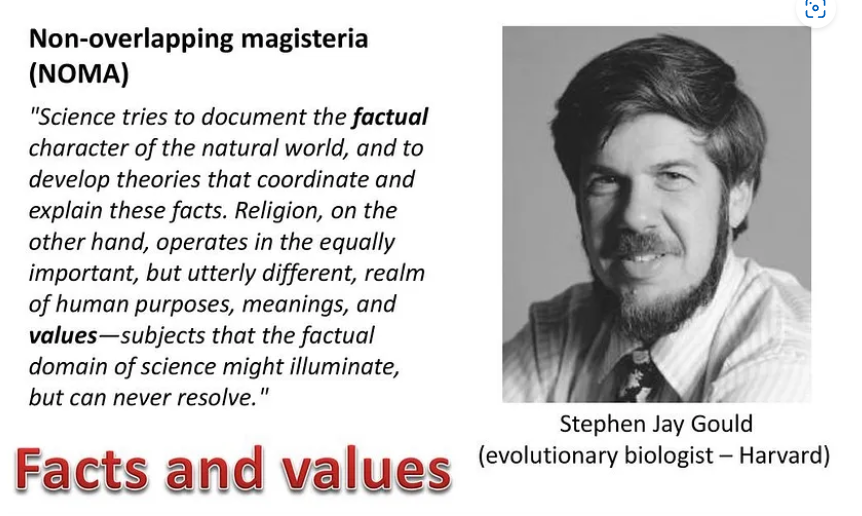

If Not Science, Then What?

Recall that Carnap concluded that “there is no question whose answer is in principle unattainable by science”.

So if the argument is that some answers aren’t attainable by the sciences, then by what discipline, philosophy, theory, domain or group/person are they attainable by?

It can be supposed that this depends on the question or the precise subject.

So, to start off with a trivial example, would we expect the sciences to have an answer to this question? -

What is the the greatest rock song of all time?

Or:

What is the true religion?

More strongly:

Is war ever right?

Let’s just say that the sciences can’t give us answers to these questions.

That may be because there can’t be a answer to them (at least not a conclusive answer). That said, the sciences may help with data, arguments, evidence, facts, etc. The problem is that these things alone will still never provide an answer.

More specifically, which facts, data, evidence, etc. would establish what the greatest rock song of all time is? Some people may offer certain facts, data or evidence to help their case, but would they alone establish this?

Say that someone states that ‘Making Your Mind Up’ (by the “power combo” Bucks Fizz) is the greatest rock song ever because it has sold the most. Thus, we can make the point that the rock song that sells the most is by definition the greatest rock song ever. However, that’s a mere stipulative definition. There’s no reason why everyone — or even anyone — should accept this definition of the greatest rock song ever.

So other people will define the greatest rock song ever in other ways and by other standards.

The problem is that these other accounts won’t be conclusive (or definitive) either.

This is the reason why the sciences may have a problem with providing answers to these questions. Again, this isn’t because the questions (or subjects/issues) “transcend science”. It will be because, in a strong sense, there are no answers at all. Thus, it’s because there are no answers at all that such questions are deemed to transcend science. It’s not that answers are indeed forthcoming, and those answers transcend science.

Or, rather, there are many answers that many people will give to these questions. However, none of them can be established as being true or even correct.

The same goes for the question, “Is war ever right?”.

Apart from it being a highly generalised question, it supposedly transcends the sciences not simply because it belongs to the unique realm of philosophy, religion, ethics or morality. It transcends the sciences because no tests, data, observations, evidence, facts, etc. could ever establish a (conclusive?) answer to that question. Again, that’s because, in a strong sense, there is no answer…

Or, rather, there are many answers that many people will give to this question. However, none of them can be established as being true.

So, in these cases, it’s not that there are questions which fall to domains other than the sciences because they transcend science in some strange or indefinable ways. Rather, no genuine answers to these questions will ever be forthcoming whichever religious person, philosopher, theorist, etc. claims to have the answers.

As for putting Carnap’s opening passage in its general context.

You Needn’t Be a Carnapian or a Logical Positivist

All the above isn’t a categorical defence of Rudolf Carnap’s logical positivism.

So, sure, there are problems with both Carnap’s own positions, and with logical positivism generally.

Is that a surprise?

For example, it’s easy to find Carnap’s views about the extremely circumscribed role of philosophy to be a little off-putting. (The same can be said about Wittgenstein’s positions on philosophy from the 1920s to his death in 1951.) Similarly, Carnap’s views on the “immediately given” — and how such a thing was once believed to provide the fundamental basis of science — seems a little old-fashioned today.

That said, perhaps most — or even all — philosophical positions from the 1920s seem a little old-fashioned today. Similarly, perhaps almost all philosophical views from today will seem a little old-fashioned at the beginning of the 22nd century… and probably long before that!

What’s more, there are problems with other philosophical movements and positions from the 1920s and beyond, just as most other people will have problems with other movements and other positions from that period and beyond.

What’s more, it was former logical positivists, the admirers of logical positivism and those philosophers who were very sympathetic to science who (to be rhetorical for a moment) destroyed logical positivism. In other words, religious (or “spiritual”) commentators, idealists, postmodern philosophers, poststructuralists, etc. didn’t destroy logical positivism. Rather, these people simply sneered at logical positivism long after philosophers such as Quine, Popper, Putnam, Strawson, Goodman, Ayer, etc. had already dealt with many of its flaws. In other words, many religious, postmodernist, poststructuralist, idealist, etc. critics of logical positivism simply picked up the crumbs which had been left for them by those aforementioned philosophers — all of whom were very positive toward science generally.

To sum up.

What the logical positivists wrote and claimed (from the 1920s to the 1940s) is gone over with a fine tooth comb by self-styled advocates of anti-scientism. To such critics, then, it’s as if logical positivism was the only philosophical movement which took wrong turns and claimed things which can be disputed.

No comments:

Post a Comment