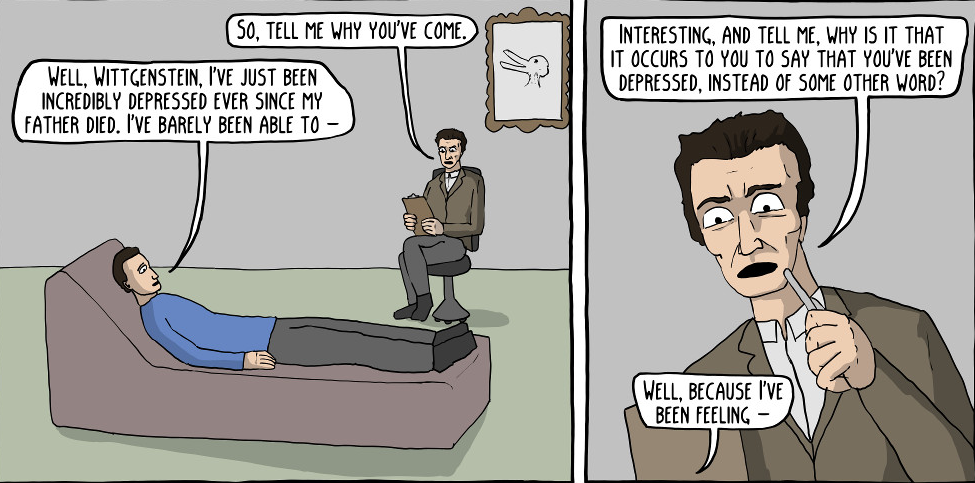

Ludwig Wittgenstein offered his readers both therapy and philosophy. That (as it were) fusion is discussed in this essay. The following also focuses on Simon Blackburn’s critical reading of Wittgenstein. This reading puts Wittgenstein in the role of both a philosophical therapist, and someone who believed that philosophy itself is — or should be — therapy. More relevantly, Blackburn argues that this stance ultimately leads to “intellectual suicide”.

“Wittgenstein imagined that the philosopher was like a therapist whose task was to put problems finally to rest, and to cure us of being bewitched by them. So we are told to stop, to shut off lines of inquiry, not to find things puzzling nor to seek explanations. This is intellectual suicide.”

— Simon Blackburn

[This passage can be found in Blackburn’s book Essays in Quasi-Realism.]

Those words from the English philosopher Simon Blackburn (1944-) seem to contain at least some truth. After all, Wittgenstein did once say that “philosophical problems should completely disappear”. (Of course, these five words need to be placed in context.)

To repeat Blackburn’s final two sentences:

“So we are told to stop, to shut off lines of inquiry, not to find things puzzling nor to seek explanations. This is intellectual suicide.”

So, again, it’s not immediately clear that Blackburn’s words are an entirely accurate or faithful account of Wittgenstein’s intent. Moreover, they also seem a little rhetorical.

In any case, many — even most — philosophers have also claimed to “put [at least certain] problems finally to rest”. Or, at the very least, they’ve said that this was their aim. However, this was usually done by providing answers to those problems, not by offering a philosophical therapy which cures philosophers — as well as others — of the psychological need for philosophical answers.

To return to the opening passage from Blackburn:

“Wittgenstein imagined that the philosopher was like a therapist whose task was to put problems finally to rest, and to cure us of being bewitched by them.”

The issue of whether (all? most? many?) philosophers really are “bewitched” by philosophical “problems” needs to be tackled — although not in this essay. In other words, didn’t Wittgenstein only have his eyes on a small subset of philosophers when he advanced his therapeutic positions?

It’s now worth saying that Blackburn isn’t entirely alone in his critical reading of Wittgenstein.

Take the views of the British philosopher Paul Horwich.

In a New York Times article, Horwich stated that Wittgenstein believed the following:

“There are no startling discoveries to be made of facts, not open to the methods of science, yet accessible ‘from the armchair’ through some blend of intuition, pure reason and conceptual analysis. Indeed the whole idea of a subject that could yield such results is based on confusion and wishful thinking.”

Of course, that passage isn’t as critical and rhetorical as Blackburn’s own. However, it seems to be saying vaguely similar things, if in a different way.

As already stated, Blackburn himself may not be entirely convincing. Yet is anyone entirely convincing when it comes to “reading Wittgenstein”?

Thus, if all people can do is read (or interpret) Wittgenstein, then that’s what I, as a reader, shall do.

So let’s just go with Blackburn’s reading of Wittgenstein for now. If we don’t, then we’ll only need to go to other readings of Wittgenstein instead.

All that is a roundabout way of saying that this essay isn’t yet another piece of “Wittgenstein scholarship”. (At one point, there were over 1000 publications about Wittgenstein in a single year.) Instead, it focuses on a (as it were) second-hand Wittgenstein — i.e., Wittgenstein through the eyes of Simon Blackburn.

More relevantly, Blackburn certainly used the word “therapist” in the opening passage.

Wittgenstein’s Philosophy as Therapy?

Can readers, philosophers and commentators move from only a couple (?) of uses of the word “therapy”, to concluding that Wittgenstein’s overall philosophy is therapeutic?

That depends.

Arguing that Wittgenstein advanced a philosophy-as-therapy position isn’t exactly a wild interpretation (or reading) of him. After all, Wittgenstein used the word “therapy” himself. However, he hardly used that word (or its derivatives) at all. Indeed, when people quote Wittgenstein advancing what they take to be philosophical therapy, he doesn’t actually use that word…

Not that a philosopher needs to use the actual word “therapy” in order to believe that philosophy is — or should be — therapy.

Yet we do have the following passage from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations:

“There is not a philosophical method, though there are indeed methods, like different therapies.”

In terms of capturing Wittgenstein’s position of philosophy-as-therapy, take a passage (from Philosophical Investigations again) which doesn’t actually include the word “therapy” at all. Here it is:

“The real discovery is the one that makes me capable of stopping doing philosophy when I want to. The one that gives philosophy peace, so that it is no longer tormented by questions which bring itself in question.”

Now a good — if arcane — example of this desire for philosophical “peace” can be seen when Wittgenstein tackled the infamous Liar Paradox. In a discussion with Alan Turing, Wittgenstein said:

“Think of the case of the Liar: It is very queer in a way that this should have puzzled anyone — much more extraordinary than you might think. [] Because the thing works like this: if a man says ‘I am lying’ we say that it follows that he is not lying, from which it follows that he is lying and so on. Well, so what? You can go on like that until you are black in the face. Why not? It doesn’t matter? [] it is just a useless language-game, and why should anyone be excited?”

[See my ‘When Alan Turing and Ludwig Wittgenstein Discussed the Liar Paradox’.]

The few times (even a single time?) that Wittgenstein used the word “therapy” (or its derivatives), he did so in a context that isn’t as radical — or, indeed, as objectionable (at least to some) — as it may at first seem.

In a strong sense, Wittgenstein didn’t (as it were) literally mean therapy by his word “therapy”. Or, at the least, he didn’t mean therapy in the literal sense, or in the sense that entered 20th century European and American lingo. In fact, the “discourse theorist” Jonathan Potter says that Wittgenstein simply used the word “therapy” as a convenient “metaphor from psychology”.

So if we now return to the passage quoted a few moments ago:

“There is not a philosophical method, though there are indeed methods, like different therapies.”

Wittgenstein is only talking about “philosophical method” here, not philosophy generally. Indeed, he’s actually talking about “methods” in the plural, not a single method.

Still, Wittgenstein did equate philosophical methods with what he called “therapies”.

However, it was philosophical therapies which Wittgenstein was referring to, not psychological, psychoanalytic, behavioural, spiritual or religious therapies. That said, he did (as quoted earlier) use the psychological words “[gives me] peace”, “tormented by”, etc.

The New Wittgenstein School and Therapy

Simon Blackburn (as already quoted) wrote the following:

“Wittgenstein imagined that the philosopher was like a therapist whose task was to put problems finally to rest, and to cure us of being bewitched by them.”

Now let’s quote one take on “the therapeutic approach to philosophy”:

“[It] sees philosophical problems as misconceptions that are to be therapeutically dissolved.”

This seems to be a normative position — at least in part. In other words, those who practice the therapeutic approach to philosophy are advising us (or telling us?) that (only certain?) philosophical problems can be (or must be?) “therapeutically dissolved”.

Still, that passage doesn’t tell us what it is to therapeutically dissolve a problem, and why anyone should have that aim in the first place.

To change tack a little.

There are two things which are worth distinguishing here:

(1) Wittgenstein’s own position of philosophy-as-therapy — and even if he held such a position for philosophy in general.

(2) Later Wittgensteinians who argued that much (sometimes all) of Wittgenstein’s work is therapeutic. [Not all Wittgensteinians have stressed philosophy-as-therapy.]

If we take the Wittgensteinian (i.e., rather than Wittgenstein’s) position (2).

The most (depending on philosophical taste) extreme form of Wittgensteinian philosophy can be found in the The New Wittgenstein “school”.

Philosophers in this school have argued that Wittgenstein’s early Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is just “plain nonsense”. Indeed, the Tractatus is deemed to be therapeutic (by these Wittgensteinians) precisely because it it’s also deemed to be “self-undermining and paradoxical”. (It can easily be argued that Wittgenstein himself took this position about his own book. However, see note 1.)

On the Tractatus itself.

Considering the gnomic, poetic and oracular prose style of that book, some readers may wonder how it would

“help us work ourselves out of [the] confusions we become entangled in when philosophizing”.

Unless, that is, Wittgenstein’s oracular and gnomic writing style was the perfect way to untangle philosophers.

Sure. So how does that work?

In any case, the “New Wittgenstein school” believed that the Tractatus didn’t advance any broad philosophical positions or any single philosophical project. (Not even the project of making philosophy therapy?) Instead, it was Wittgenstein’s way of getting philosophers (or his readers) to give up on philosophical speculation, as well as to give up on endlessly attempting to solve (often ancient) problems.

To sum up the New Wittgenstein position, this is how Alice Crary (a New Wittgensteinian) puts her (or Wittgenstein’s) position:

“Wittgenstein’s primary aim in philosophy is — to use a word he himself employs in characterizing his later philosophical procedures — a therapeutic one. These papers have in common an understanding of Wittgenstein as aspiring, not to advance metaphysical theories, but rather to help us work ourselves out of confusions we become entangled in when philosophizing.”

Now what of Wittgenstein’s “quietism”?

Philosophical Quietism?

Perhaps the passage which best captures Wittgenstein’s quietist position is this (often-quoted) one:

“Philosophy may in no way interfere with the actual use of language, it can in the end only describe it.

“For it cannot give it any foundation either. It leaves everything as it is.”

That final sentence (i.e., “[philosophy] leaves everything as it is”) perfectly expresses philosophical quietism… Or, at the least, it seems to.

However, a quietist position toward philosophy may not itself be quietist philosophy.

In other words, when Wittgenstein told philosophers to (as it were) be quiet, he said that in a (philosophically) loud voice.

Indeed, advising philosophers not to “interfere with the actual use of language”, and to “leave[] everything as it is”, doesn’t seem quietist at all. These bits of philosophical advice seem to be, at best, normative. And, at worst, categorical.

Oddly enough, Simon Blackburn himself (in his A Dictionary of Philosophy) puts a position that distances Wittgenstein from quietism. He wrote:

“In philosophy the doctrine doubtfully associated with Wittgenstein. [] Wittgenstein sympathized with this but his own practice include a relentless striving to gain a ‘perspicacious representation’ of perplexing elements in our thought.”

Now take the following account of what philosophical quietists believe. Apparently, they believe that

“advancing knowledge or settling debates (particularly those between realists and non-realists) is not the job of philosophy, rather philosophy should liberate the mind by diagnosing confusing concepts”.

The following questions now seem somewhat obvious:

(1) Isn’t philosophical Quietism itself a way of “settling debates”? (It settles debates by — among other things — “dissolving problems”.)

(2) Doesn’t philosophical Quietism settle the debate by “liberating the mind” via the method of “diagnosing confusing concepts”?

(3) More narrowly, doesn’t philosophical Quietism settle the debate between realists and non-realists by (completely) rejecting both realism and non-realism? [See note 2.]

Of course, it can be assumed here that quietists would deny (or would they?) that they’re attempting to settle the debate. However, why should non-quietists accept that (seemingly modest) denial?

What’s more:

(1) Doesn’t philosophical Quietism advance the knowledge that philosophers use “confusing concepts”? [Sure, we can now ask: What is knowledge?]

(2) Doesn’t philosophical Quietism advance the knowledge that the realism-vs.-nonrealism debate is bogus?

Of course, it can be assumed here that quietists would claim (or would they?) that these aren’t actually attempts to advance knowledge at all. However, why should non-quietists accept that (seemingly modest) claim?

It’s also worth saying here that (perhaps) one can be a Wittgensteinian without also being a quietist. Indeed, (perhaps) one can be a Wittgensteinian without also believing that philosophy is therapy.

So now take these words from Wittgenstein himself:

“It is not our aim to refine or complete the system of rules for the use of our words in unheard-of ways.”

The Wittgensteinian P.M.S. Hacker (Peter Hacker) brings Wittgenstein up to date (i.e., by discussing neurophysiologists and psychologists) without necessarily committing himself to the philosophy-as-therapy position. Yet Hacker still takes almost exactly the same position as Wittgenstein in the following:

“[Expressions] can and are violated by unconsciously crossing ordinary uses of expressions with half-understood technical ones.”

Hacker believes in what’s been called the “linguistic-therapeutic approach” to philosophy. In other words, he believes that the words and concepts used by everyday people should be taken as given by philosophers… and also (it seems) by scientists. Consequently, he sees the role of philosophy (as did Wittgenstein) as one of dissolving (or resolving) philosophical problems by examining (among other things) how words are actually used in everyday life. More precisely, Hacker deems philosophical problems to be primarily conceptual in nature. To him, this also means that these problems can be dissolved (or resolved) purely by “linguistic analysis”.

Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Anti-Philosophy

Wittgenstein did a lot of philosophy in order to reach his (scare-quoted) “therapeutic” conclusions. Indeed, his critical statements about philosophy are themselves philosophical.

Now do some of Wittgenstein’s statements and positions on philosophy land him in self-referential quagmires — at least to some degree?

Thus, three questions can now be asked:

(1) Didn’t Wittgenstein require philosophical arguments (or at least philosophical positions) to advance the thesis that “the philosopher is like a therapist”?

(2) Didn’t Wittgenstein require philosophical arguments (or at least philosophical positions) to advance the idea that philosophers should “put problems to rest”?

(3) Didn’t Wittgenstein require philosophical arguments (or at least philosophical positions) to state that philosophers are bewitched by problems, and that curing them of that bewitchment is the role of philosophy?

Of course, Wittgenstein never claimed that his statements and positions weren’t philosophical. And Wittgensteinians have never claimed that they weren’t philosophical either.

So it can be argued that Wittgenstein (perhaps like the “historian” — rather than therapist — Jacques Derrida) wasn’t attempting to close the book of philosophy: he was simply wanting to point philosophy in new directions.

Yet there’s much dispute about all this.

(As there is when it comes to literally everything Wittgenstein wrote and said.)

So this is the time that readers may want to consult the more upfront and explicit “anti-philosophy” readings of Wittgenstein…

Notes

(1) The German philosopher Hans-Johann Glock argued that this “plain nonsense” account of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus is

“at odds with the external evidence, writings and conversations in which Wittgenstein states that the Tractatus is committed to the idea of ineffable insight”.

(2) At least according to the philosopher Alexander Miller. He wrote:

“Philosophers who subscribe to quietism deny that there can be such a thing as substantial metaphysical debate between realists and their non-realist opponents (because they either deny that there are substantial questions about existence or deny that there are substantial questions about independence).”

No comments:

Post a Comment