See my ‘Margaret Boden on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Consciousness’ for a short introduction to both Margaret Boden herself, and her book AI: Its Nature and Future.

When it comes to qualia and artificial intelligence (AI), Boden discusses the ideas and theories of Paul Churchland and Aaron Sloman.

So let’s firstly deal with the Canadian philosopher Paul Churchland.

Paul Churchland on Qualia

At first, Margaret Boden presents Paul Churchland as an identity theorist (see ‘Identity Theory’), rather than as an eliminativist materialist (see ‘Eliminative materialism’) . In Boden’s own words:

“For Churchland, this isn’t a matter of mind-brain correlation: to have an experience of taste simply is to have one’s brain visit a particular point in that abstractly defined sensory space.”

This means that Churchland doesn’t offer us those “mere correlations” which anti-physicalists and others sniff at.

Indeed, if you only stress correlations, then (arguably) you’ll always need to deal with David Chalmers’ “hard problem”. After all, if brain state X is (always?) correlated with the bitter taste of a lemon, then Chalmers and others can always ask the following question:

Why does brain state X give rise to the bitter taste of lemon (even if that taste is correlated with that brain state)?

In any case, Churchland isn’t an eliminativist about qualia: he’s actually an eliminativist about propositional attitudes. [See Churchland’s ‘Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes’, which was published way back in 1981.]

To clarify. Churchland, as a materialist, isn’t out to eliminate qualia: he’s out to identity qualia with (to use Boden’s words) “particular point[s] in that abstractly defined sensory space”.

So Churchland doesn’t deny (or reject) qualia: he simply offers us his own account of them. [See note 1 on Dennett’s own account of consciousness.]

In Boden’s own words:

“[Paul Churchland] offers a scientific theory — part computational (connectionist), part neurological — defining a four-dimensional ‘taste-space,’ which systematically maps subjective discrimination (qualia) of taste onto specific neural structures. The four dimensions reflect the four types of taste receptor on the tongue.”

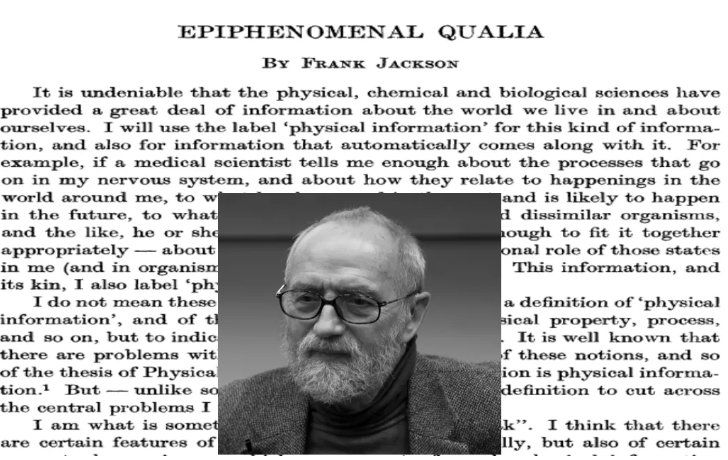

Of course, some anti-physicalists, all dualists and others believe that qualia cannot possibly be (specific or otherwise) “neural structures”. That’s simply because they don’t deem qualia to be physical in nature at all. Indeed, even some physicalists don’t believe that a token or type neural structure and a token or type quale can be one and the same thing.

Identity theorists (old and new), on the other hand, do believe that they are one and the same thing.

More clearly. To some anti-physicalists, and to all dualists, the idea that

“all phenomenal consciousness is simply the brain’s being at a particular location in some empirically discoverable hyperspace”

is actually to eliminate qualia completely — if only according to their own definition. So perhaps such people could state the following:

Brain states are brain states. Qualia are qualia.

Or in Boden’s own terminology:

Particular locations in some empirically discoverable hyperspace are particular locations in some empirically discoverable hyperspace. Qualia are qualia in no particular location.

… But it’s not just mere correlations which physicalists need to deal with.

Colin McGinn and David Chalmers on Qualia

Margaret Boden also mentions (if only in passing) the British philosopher Colin McGinn and his own stance on the “causal link” between qualia and “the brain”. According to Boden, McGinn

“argued that humans are constitutionally incapable of understanding”

that link.

Yet perhaps this too is just another variation on the mere-correlations theme.

After all, and like most of the critics of physicalism, McGinn accepts that the correlations exist, and even that they’re relevant and important. However, how can we (philosophically) understand those correlations? How can we understand — or explain — the causal (or otherwise) link between a bit of the brain (or even the brain taken in toto) and, say, the quale we experience when drinking bitter lemon juice?

Boden covers this precise issue again in another place in her AI: Its Nature and Future. (This time when discussing the position of John Searle.) In line with McGinn, Boden states that

“qualia being caused by neuroprotein is no less counter-intuitive, no less philosophically problematic”

than stating that

“computers could really experience blueness or pain, or really understand language” .

Now what about the Australian philosopher David Chalmers?

Even though Chalmers (like McGinn) will be happy to accept that qualia are mapped onto specific neural structures, then that still leaves his “hard problem of consciousness” untouched. In other words:

Why does neural structure X lead to, say, the specific bitter taste of a lemon?

Moreover: Why don’t lemons taste like dog shit or like nothing at all?

But Hang on!

All this depends on what we take qualia to be in the first place. (See later section.)

Now for the philosopher and researcher Aaron Sloman on his (as it were) AI account of qualia.

Aaron Sloman on Qualia

Like Paul Churchland earlier, Aaron Sloman (whom Boden refers to many times in her book) doesn’t eliminate qualia either. Far from it.

Basically, Sloman sees qualia as being “hosted” by the brain. Thus, there’s clearly no elimination of qualia here.

Indeed, according to Sloman (if via Boden), qualia don’t even require a biological brain!

It seems, them, that Sloman’s way of looking at things could also be adopted by idealists, dualists, and even by Platonists…

Platonists?

Take what the physicist and mathematician Roger Penrose argued on this subject.

Penrose discussed what he called a “qualium” (i.e., the singular of ‘qualia’), and its relation to the brain.

Penrose wrote:

“Such an implementation [of an algorithm] would, according to the proponents of such a suggestion, have to evoke the actual experience of the intended qualium.”

If the precise hardware doesn’t at all matter, then only the given algorithm (or the virtual machine) matters. Of course, the algorithm (or virtual machine) would need to be implemented… in something.

Yet this may not at all be the case if we follow this AI position to its logical conclusion.

Are Qualia are Ineffable, Private, and Causally Salient?

As already hinted at, it can be said that Sloman’s position on qualia and consciousness may be somewhat appealing to some anti-physicalists and anti-reductionists in that he argues that we can’t (in Boden’s words) “identif[y] qualia with brain processes”. What’s more, consciousness and qualia “can’t be defined in the language of physical descriptions”…

Yet, despite all that, qualia still have “causal effects”.

So Sloman’s account of qualia (if accurately presented by Boden) is odd in that, on the surface at least, it perfectly squares with the (as it were) traditional account of qualia. Yet, at the same time, it’s also bang up-to-date in terms of its scientific references.

Why use the words “traditional account of qualia” here?

Sloman believes that qualia are ineffable and private, yet also of causal relevance when it comes to human subjects.

In terms of Sloman’s position on ineffable qualia, Boden writes:

“Moreover, they cannot always be described — by higher, self-monitoring, levels of the mind — in verbal terms. (Hence their ineffability.)”

In terms of privacy, Boden continues:

“They can be accessed only by some other pars of the particular virtual machine concerned, and don’t necessarily have any behavioural expression. (Hence their privacy.)”

Finally, in terms of causality, Boden finishes off with the following words:

“They can have causal effects on behavior (e.g. involuntary facial expression) and/or on other aspects of the mind’s information processing.”

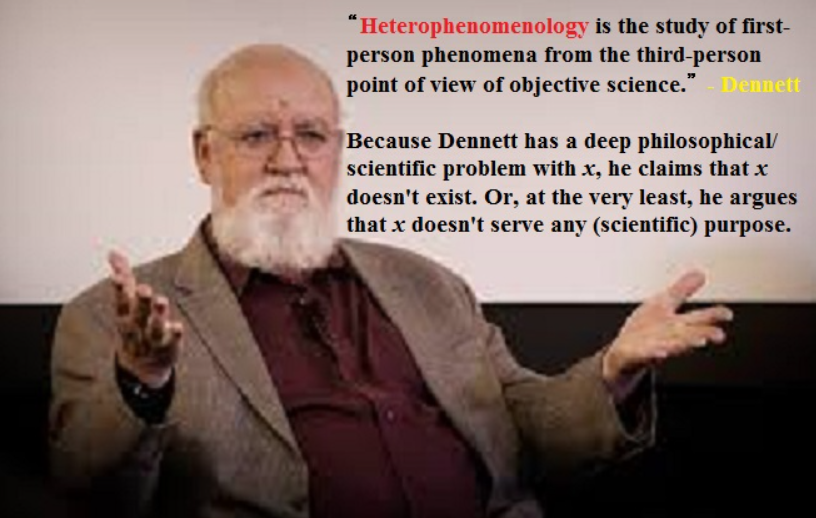

Most (if not all) of the above seems to go against Daniel Dennett’s case against qualia. What’s more, the addition of up-to-date scientific jargon (such as “computational states”, “information processing”, “virtual machines”, etc.) doesn’t seem to make much difference to that.

Privacy

In terms of privacy again.

In broad terms, mental privacy has always been problematic in philosophy. However, perhaps Sloman’s way around this is to bring on board (as Boden puts it) “other parts of the particular virtual machine”.

In Boden’s words, qualia

“can be accessed only by some other parts of the particular virtual machine concerned, and don’t necessarily have any behavioural expression”.

Specifically, qualia

“can be accessed only by some other pars of the particular virtual machine concerned”.

Thus, it may seem that we don’t have the old-style privacy here in which a human subject is the sole (as it were) owner of whatever it is that’s going on inside his mind and brain. Instead, we have different “parts” of a “machine”.

Yet it’s still the same (or singular) virtual machine that’s doing the accessing — even if it does have parts.

So does privacy still rule okay?

Sloman (at least as presented by Boden) has the same position on privacy as the philosopher Owen Flanagan. That is, Flanagan accepts that (mental) privacy exists. However, he doesn’t see it as being such a big deal for naturalism. (At least it’s not a big deal to Flanagan himself, as well as to other naturalists.)

Epiphenomenalism

One important point stressed by Sloman (if in Boden’s words) is that qualia “don’t necessarily have any behavioural expression”. (Boden adds: “Hence their privacy.”)

In this passage we have an account of qualia’s causal effects, as well as a hint that they can also be epiphenomenal…

However!

A particular quale may not be behaviourally expressed, and still not be epiphenomenal. After all, this reference to “behavioural expression” is usually a reference to the subject verbally reporting his quale — or even just physically reacting to it. However, the quale may still be causally relevant even without such (as it were) outward signs.

Despite the seemingly Cartesian account of qualia’s privacy, ineffability, and non-necessary link to behaviour, Sloman still believes that qualia

“can have causal effects on behavior (e.g. involuntary facial expression) and/or on other aspects of the mind’s information processing”.

This seems obviously true.

If someone tastes a bitter lemon and grimaces, then clearly the bitter quale of a lemon has had a “causal effect[] on behavior”…

But is it a philosophically-conceived quale that we’re talking about here?

It depends.

However, let’s return to the statement that qualia “don’t necessarily have any behavioural expression”. This possibility would definitely go against Daniel Dennett’s stance on this matter.

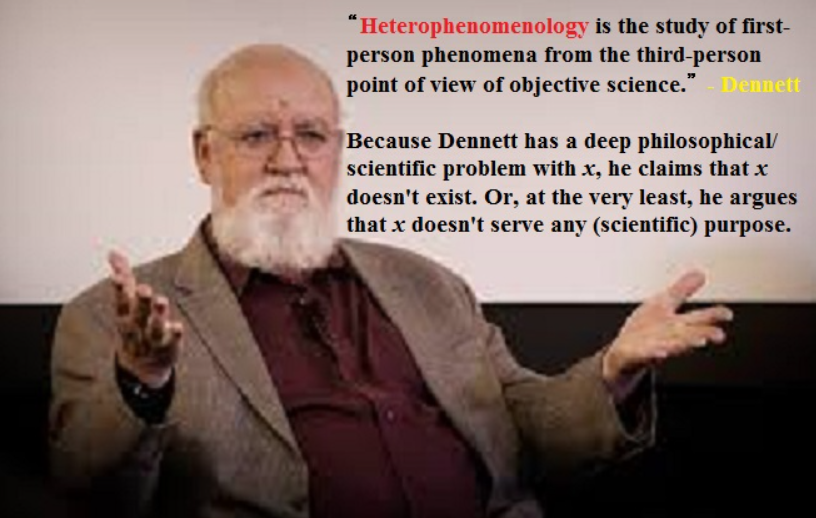

Dennett on the Verbal Reports of Qualia

If qualia don’t “have any behavioural expression”, then they constitute (to quote Wittgenstein) “a wheel that can be turned though nothing else moves with”. (This position also goes against Dennett’s heterophenomenological stance on all qualia-talk.)

So can we also ask the following question here? —

If qualia aren’t behaviourally expressed, then how do we know that they exist at all?

Sure, a human subject may verbally report that his qualia exist. However, how would other human subjects know that his qualia exist? Or, less strongly, how would other subjects know that they his qualia have the qualities and characteristics which he says they have?

All this leads on to a fairly extensive section of Boden’s book in which she tackles Daniel Dennett’s position on this issue.

Boden actually quotes one of Dennett’s own dialogues between himself and someone called Otto. The following is part of Boden’s own extract from that dialogue:

[Otto] Look. I don’t just mean it. I don’t just think there seems to be a pinkish glowing ring; there really seems to be a pinkish glowing ring!

[Dennett] Now you’ve done it. You’ve fallen in a trap, along with a lot of others. You seem to think there’s a difference between thinking (judging, being of the firm opinion that) something seems pink to you and something really seeming pink to you. But there is no difference. There is no such phenomenon as really seeming — over and above the phenomenon of judging in one way or another that something is the case.”

This is essentially a position both against the ineffability of qualia, and in support of Dennett’s heterophenomenology.

Basically, Otto can’t rely on his own experience of qualia to defend their reality or existence.

So all we have are Otto’s “judgements” about, in this particular case, a particular quale.

Firstly, Otto claims to experience a “pinkish glowing ring”. To Dennett, this is fair enough. That is, he doesn’t reject that claim out of hand (or as it stands).

However, what of the quale itself?

Is it real?

Does it exist?

What qualities and characteristics does it have?

Well, Otto says that this quale is real because he experiences it. More specifically, Otto states that it “seems to be a pinkish glow”.

This means that Otto has moved on from this quale’s existence (or reality), to referring to his own personal (as it were) seemings.

So these seemings are surely real?

Dennett questions this too.

In response, Otto ups the ante by stating that he doesn’t don’t “just mean it” about the seeming. He continues:

“I don’t just think there seems to be a pinkish glowing ring; there really seems to be a pinkish glowing ring!”

So, again, we’ve moved from an implicit claim that the quale is real or exists, to the seeming-of-a-pinkish-glow being real or existing.

Again, forget the quale itself, what about the seeming-to-have-a-pinkish-glow?

Dennett’s main point is that all he has to go on (all we have to go on) are (at first) Otto’s judgments about the pinkish glow, and then, secondly, his judgments about the seemings-of-a-pinkish-glow.

Thus, we never get to either the quale or the seeming itself — only to the “verbal reports” about both.

However, is that a reason to deny reality or existence to (as it were) what’s behind the verbal reports?…

But what’s behind the verbal reports?

Are we in a loop of judgments here?

Note:

(1) This is parallel to Daniel Dennett’s position on consciousness. It’s not that he believes that “consciousness should be explained away”. It’s that his account of consciousness is at odds with at least some mainstream, as well as also philosophical, accounts of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment