(i) Introduction

Opening note:

The word “context” will be used in this essay a fair few times. It’s a catchall term for capturing the circumstances, social/psychological backgrounds, historical/social surroundings, etc. which give birth to the ideas and beliefs of philosophers and scientists.

However, what follows isn’t going to be sociological, psychological and/or historical in nature. Instead, it’s about the role of context when specifically dealing with the ideas, beliefs and theories of philosophers and scientists.

Ironically (or perhaps not), then, I’m going to be offering arguments (mainly aimed at analytic philosophers) as to why concentrating entirely on arguments may not always be the best — and only — approach when doing philosophy.

Introduction: The Contexts of Discovery

In philosophy, and perhaps generally, should we completely ignore the aetiologies and contexts of scientists' and philosophers’ beliefs, ideas and theories?

One reason it’s unwise to do so is that from the (as philosophers put it) context of discovery and belief we can gain a better understanding of the beliefs and ideas themselves. Thus, the contexts (whether psychological, historical, political, etc.) in these cases would only be a means to a philosophical end.

To put that another way. By learning about contexts, we may actually gain an insight into — and a better understanding of — philosophers’ and scientists’ beliefs and ideas themselves.

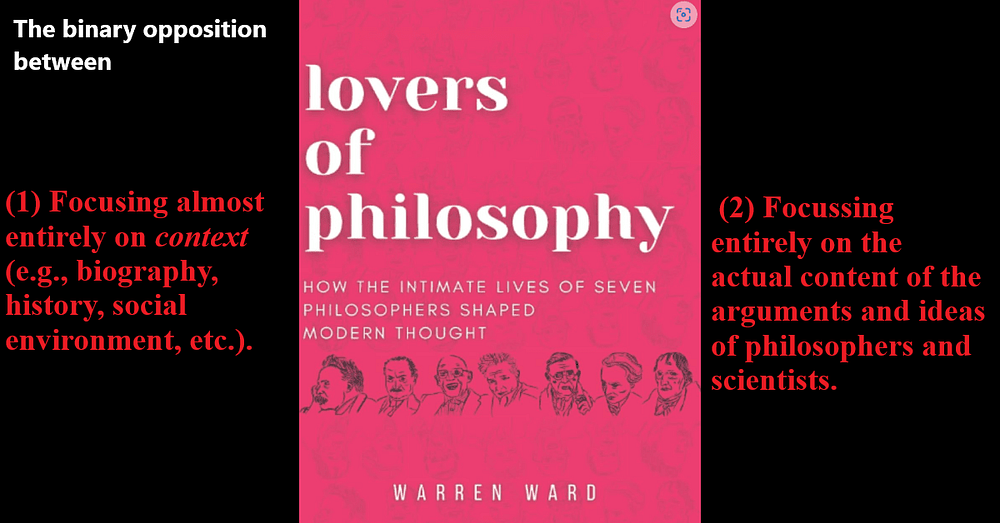

Thus, the following binary opposition between

(1) Focussing almost entirely on context (e.g., biography, etc.).

and

(2) Completely ignoring everything except for the actual arguments and ideas of individuals.

must be questioned.

Many (even most) analytic philosophers may well go too far in the direction of (2), whereas many other people go too far in the direction of (1).

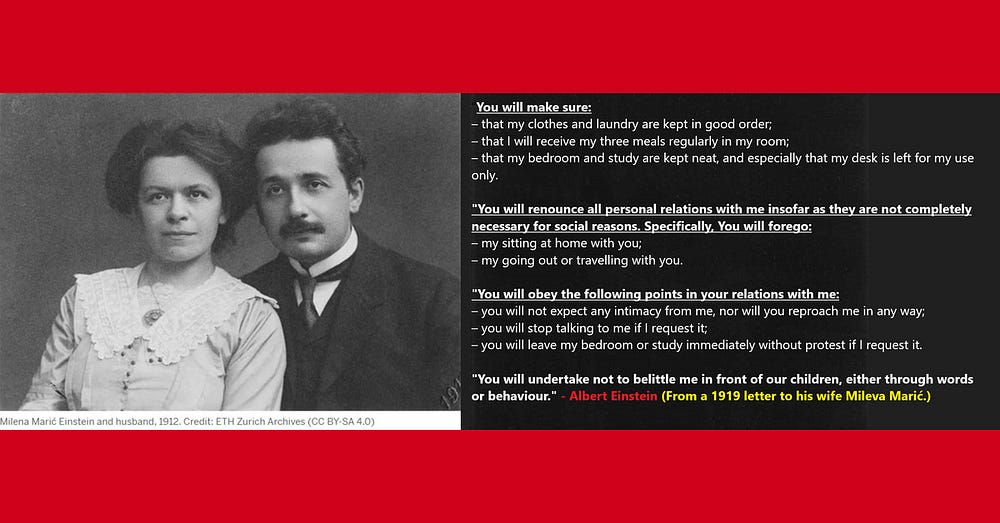

Two Cases: Immanuel Kant and Philip Goff

I once wrote an essay on Immanuel Kant in which I mentioned his prior Pietistic Lutheranism. Indeed, in that same essay, I also mentioned the English philosopher Philip Goff and his prior politics. [See my ‘Do the (Hidden) Motives of Philip Goff and Immanuel Kant Matter?’.] More concretely, I attempted to tie the prior non-philosophical beliefs, ideas and values of both Kant and Goff to their later philosophical ideas and theories. [See the many essays, papers and books on ‘Kant and Pietism’ here.]

However, in both cases, I didn’t rely exclusively on context. Indeed, context simply served what I took to be a philosophical and argumentative purpose.

More specifically, I used the words “ulterior motives” in the essay on Kant. And I happily acknowledged that I too had an ulterior motive for arguing that Kant had moral — and even religious - ulterior motives for advancing his own philosophies. Indeed, I quoted Kant (more or less) admitting that he had such an ulterior motive.

For example, in The Critique of Pure Reason, Kant wrote the following passage:

“[T]here can only be one ultimate end of all the operations of the mind. To this all other aims are subordinate, and nothing more than means for its attainment. This ultimate end is the destination of man. [] The superior position occupied by moral philosophy, above all other spheres.”

This is a long statement that “moral philosophy” should be — or actually is — First Philosophy. In other words, the quote above is an honest acknowledgement by Kant of his own moral — and perhaps religious - ulterior motive. [The mid-20th-century French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas explicitly stated that Ethics is — or at least it should be — First Philosophy. See here.]

Thus, Kant stated that “all the operations of the mind” (including all Kant’s own philosophising in metaphysics, epistemology, etc.) were nothing more than

“means for [the] attainment [of the] ultimate end [of] moral philosophy”.

There’s more — strictly philosophical — evidence of Kant’s religious and moral a priori when it came to his attempted destruction of the Ontological Argument for the existence of God.

In this precise technical case, Kant attempted to demonstrate that the word “‘exist’ is not a predicate”. And, by doing so, he believed that the support underneath the Ontological Argument had been taken away. This backed up Kant’s prior (Protestant) Pietism in that “faith” (not proof, evidence or argument) became the true source of his religious and moral beliefs.

Of course, I suspect that some readers won’t interpret Kant’s words as I’ve just done.

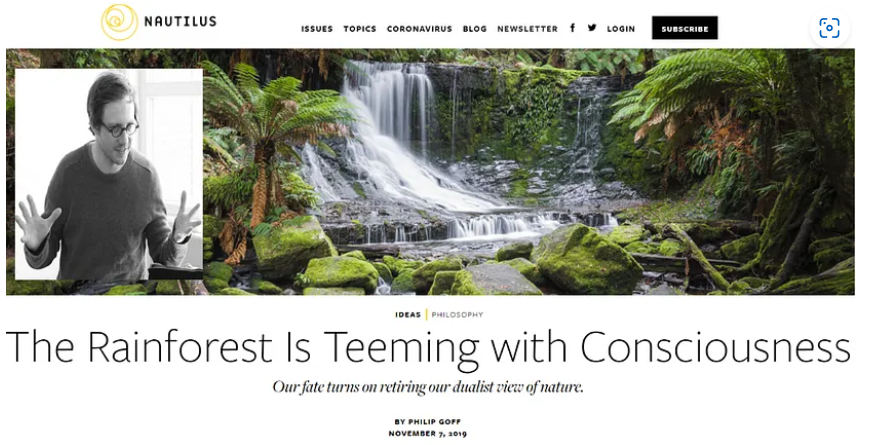

So what about Philip Goff?

Relevantly (or ironically) enough, Goff himself once warned other philosophers and scientists against “believing what they want to believe”. So that’s a good reason to quote a few passages from Goff himself (as found in the book Galileo’s Error):

“I agree on the benefit of panpsychism to eco-philosophy, and have in the past made similar arguments.”

“The terrible mass destruction of forests we witnessed in Brazil in recent years under Bolsonaro, have a different moral character if we see them as the burning of conscious organisms.”

“[Panpsychism] entails that there is, in a certain sense, life after death.”

To me at least, these passages speak for themselves.

[There are another ten passages — of a very similar kind — from Goff which can be read in note 1 at the end of this essay.]

So does anyone write anything at all without motives of some kind?

Too Much Context?

Perhaps, then, this may be an argument against even mentioning such a universal — thus, possibly banal — phenomenon. Wouldn’t it be like mentioning the fact that water is wet?

In any case, most people do mention (or simply note) context. Analytic philosophers, on the other hand, generally don’t mention or write about context. (At least that’s part of the self-image of many analytic philosophers.) However, they too must still think about such things.

Perhaps they wouldn’t deny this.

However, they would say that contexts are irrelevant to philosophy itself.

Yet there are, of course, dangers to citing contexts.

Julian Baggini (who’ll be featured later in this essay) picked up on one example. He wrote:

“Have you never, in an immune system-like response, repelled a view that contradicts your own with a ‘they would say that’?”

Thus, if Philip Goff denied (or simply played down) all the contexts I’d highlighted, then all I’d need to say in response is: He would deny that. Wouldn’t he.

Of course, all Goff (or one of his supporters) needs to say back is: Paul Murphy would say that. Wouldn’t he.

More critically, my citations or examples of context may be false. They may be irrelevant. Or, in Baggini’s eyes, they may simply be unfalsifiable.

In any case, the main problem (at least in philosophy) is relying exclusively on contexts, and also drawing too much out of them. Indeed, this approach too can be taken to extremes… as we’ll now see.

The following is an extreme example of someone relying on context, biography and someone’s supposed psychology in order to escape from argument.

The American mathematician and physicist Alan Sokal, and the physicist and philosopher Jean Bricmont, wrote (in their book Intellectual Impostures) the following words on the French critic and writer Philippe Sollers:

“Philippe Sollers asserts [] that our private lives ‘merit investigation’: ‘What do they like? What paintings do they have on their walls? What are their wives like? How are those beautiful abstract statements translated in their daily and sexual lives?’

Sokal and Bricmont continued:

“Well! Let’s concede once and for all that we are arrogant, mediocre, sexually frustrated scientists, ignorant in philosophy and enslaved by a scientistic ideology (neoconservative or hard-line Marxist, take your pick).

“But please tell us what this implies concerning the validity or invalidity of our arguments.”

What can you say to people like Philippe Sollers?

Well, Sokal and Bricmont themselves could have responded by stating the following:

I believe that Philippe Sollers’ private life merits investigation: What does he like? What paintings does he have on his walls? What is his wife like? How are Sollers’ psychoanalytic questions translated into his own daily and sexual life?

All this tangentially brings up the subjects of objectivity and bias.

The Objectivity of a Free Market Think Tank

There is a conundrum here, which the English philosopher Julian Baggini captures with his own specific example. He wrote:

“If a free market think tank reports that free markets are a good thing, we might at least question the objectivity of the research.”

However, Baggini concluded:

“Nevertheless, that research should stand or fall on its own merits.”

So surely the context here can’t be irrelevant.

In any case, of course a “free market think tank” would report that “free markets are a good thing”. The clue, after all, is in the words “free market think tank”.

(It can be supposed that — in theory at least— there could be such a free market think tank whose job it was to criticise the free market, question its very existence, etc.)

In addition, what did Baggini mean by the word “objectivity”?

To state the obvious. A think tank which criticised this free market think tank wouldn’t be objective either. Similarly, if a free market think tank is by definition lacking in objectivity, then surely the person criticising that think tank is lacking in objectivity too.

What’s more, even if everything this free market think tank states is true, accurate, and evidence-based, its reports and research would still be selective and issue-led. Similarly, a critic of this think tank may also offer truthful, accurate, or evidence-based criticisms of this think tank. Yet he too will be selective and issue-led.

So would any think tank (or any person) be truly objective on this subject? Indeed, what does that word “objective” even mean in this specific context?…

Perhaps all this is precisely why Baggini concluded by saying that “research should stand or fall on its own merits”.

Abortion and Those Nazis Again!

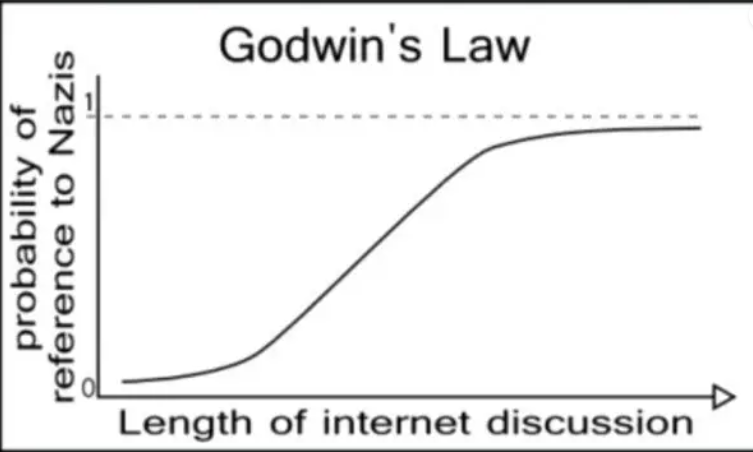

The Nazis are often mentioned in order to place ideas and beliefs in some kind of (very negative) context. In extreme cases, this is — and it should be — classed as Godwin’s law.

Take the following account of this law:

“Godwin’s law, short for Godwin’s law (or rule) of Nazi analogies, is an Internet adage asserting: ‘As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.”

Indeed, we even have reductio ad Hitlerum:

“Reductio ad Hitlerum [] also known as playing the Nazi card, is an attempt to invalidate someone else’s argument on the basis that the same idea was promoted or practised by Adolf Hitler or the Nazi Party. Arguments can be termed reductio ad Hitlerum if they are fallacious (e.g., arguing that because Hitler abstained from eating meat or was against smoking, anyone else who does so is a Nazi). []”

Julian Baggini (again) picked up on this in the case of Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor. He wrote:

“Given that Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor is a Roman Catholic, it comes as no surprise to find that he is against abortion. But it is still something of a shock to hear him compare the termination of foetal life with Nazi eugenics programmes, which he has done on several occasions. In the quote above he even evokes a comparison with the Holocaust with his reference to ‘6 million lives’.”

Two paragraphs later, Baggini concluded with the following words:

“The problem with guilt by association is that it fails to show what is actually wrong with the thing being criticized.”

Yet perhaps things aren’t so simple.

Is there really such a rigid line between using “guilt by association” (or providing some kind of context), and “show[ing] what is actually wrong with the thing being criticized”?

For a start, a Catholic (or even a non-Catholic) may say that Baggini himself was using guilt by association when he wrote the following words:

“Given that Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor is a Roman Catholic, it comes as no surprise to find that he is against abortion.”

Sure, a reader could now say:

But Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor was a Catholic! That’s just a fact.

So what about Baggini’s phrase “it comes as no surprise”?

Again, a reader could say:

Well, everyone knows that the Catholic Church is against abortion. So Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor’s position is indeed “no surprise”.

In any case and as already quoted, Baggini finished off by saying that the

“problem with guilt by association is that it fails to show what is actually wrong with the thing being criticized”.

Yet Baggini himself associates being against abortion with the Catholic Church, and he also fails to show what’s actually wrong with being against abortion…

Well, that’s surely because the chapter these words are taken from isn’t actually about abortion.

That said, the Catholic Church too has provided mountains of (good and bad) reasons as to why it believes abortion is morally wrong. It just happens to be the case that in the example cited by Baggini, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor did indeed rely exclusively on guilt by association.

So clearly this is complicated.

For a start, there may be very good reasons to associate abortion with what the Nazis did. Yet there may also be very good reasons to reject those reasons. The problem still is, however, that (guilt by) association (or context generally) shouldn’t be exclusively relied on.

The Nazis Believed Things Which Are True

As we’ve seen, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor mentioned the Nazis. Many people do. Indeed, so too does Julian Baggini. However, Baggini did so in order to get his point across.

Baggini wrote:

“The Nazis were very keen on ecology, forests, public rallies, compulsory gym classes and keep fit. [] Hitler too eschewed meat.”

Thus, those who’re against ecology, vegetarianism, etc. could mention the Nazis and/or Hitler. (In fact they often do!) However, Baggini continued:

“Nothing is bad or wrong simply because the hand of evil has touched it.”

Let’s look at this.

Most (even all) Nazis would have believed that 2 + 2 equals 4. That doesn’t thereby stop 2 + 2 equalling 4. And neither does it make the equation bad.

Yet even outside simple beliefs about arithmetic this logic may still apply.

Perhaps, then, it would be wise to come down somewhere in the middle on this issue.

We shouldn’t believe that if a somehow culpable person states P, then that makes P false — or at least probably false. And neither should we believe P is false — or simply suspect — simply because it was articulated by a person at a certain suspect point in history, or in a certain suspect environment.

Note:

(1) Here are the passages from Philip Goff, which can mainly be found in his book Galileo’s Error:

“My hope is that panpsychism can help humans once again to feel that they have a place in the universe. At home in the cosmos, we might begin to dream about — and perhaps make real — a better world.”

“Could our philosophical worldview be party responsible for inability to avert climate catastrophe?”

“The view of the mystics, in contrast, does provide a satisfying account of the objectivity of ethics… According to the testimony of mystics, it is this realization [“formless consciousness”] that results in the boundless compassion of the enlightened.”

“It is no surprise that in this worldview [“dualism” — Goff says almost identical things about “materialism” in these respects] the act of tree hugging is mocked as sentimental silliness. Why would anyone hug a mechanism?”

“Panpsychism has a potential to transform our relationship with natural world.

“[W]e now know that plants communicate, learn and remember. I can see no reason other than anthropic prejudice not to ascribe to them a conscious life of their own.”

“[I]t would be nice if reality as a whole was unified in a common purpose.”

“… if they were taught to walk through a forest in the knowledge that they are standing amidst a vibrant community: a buzzing, busy network of mutual support and care.”

“[] I also think that [panpsychism] is a theory of Reality somewhat more consonant with human happiness than rival views.”

“For a child raised in a panpsychist worldview, hugging a conscious tree could be a natural and normal as stroking a cat.”

No comments:

Post a Comment