First things first. Readers should note that the argument being advanced in the following essay isn’t that all scientists utter the absolute truth every time they open their mouths. (Thus, that we should believe literally everything scientists say.) And neither is it being put forward that all non-scientists know nothing much about any scientific subject. (In certain cases, non-scientists may actually know more than professional scientists when it comes to specific issues or subjects.)

Still, scientific testimony is a real thing.

And this is certainly more the case when it comes to some scientific subjects (such as mathematical physics generally, or string theory particularly), than when it comes to other scientific subjects.

What’s more, scientists themselves often rely on testimony. Indeed, that’s even the case when it comes to their very own specialisms!

Introduction

In my essay ‘Physicist Peter Woit on the Sociology of String Theory’ I said that, to a non-physicist such as myself, Peter Woit’s criticisms of string theory certainly seem convincing. And then, after quoting Woit’s technical take on this issue, I continued with the following passage:

“I used the words ‘to a non-physicist’ just before I quoted the long passages above. I’m not saying that all readers need to be professional physicists in order to make sense of the scientific parts. However, I certainly don’t feel qualified enough to come down either way on many of Peter Woit’s scientific pronouncements.”

I then promised to go into detail on this.

Scientific Testimony

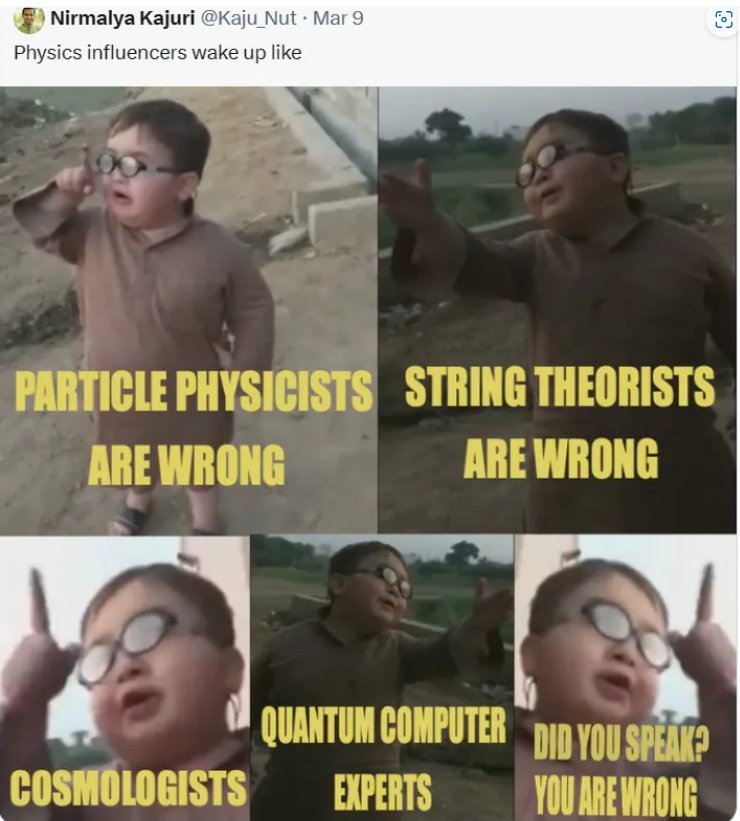

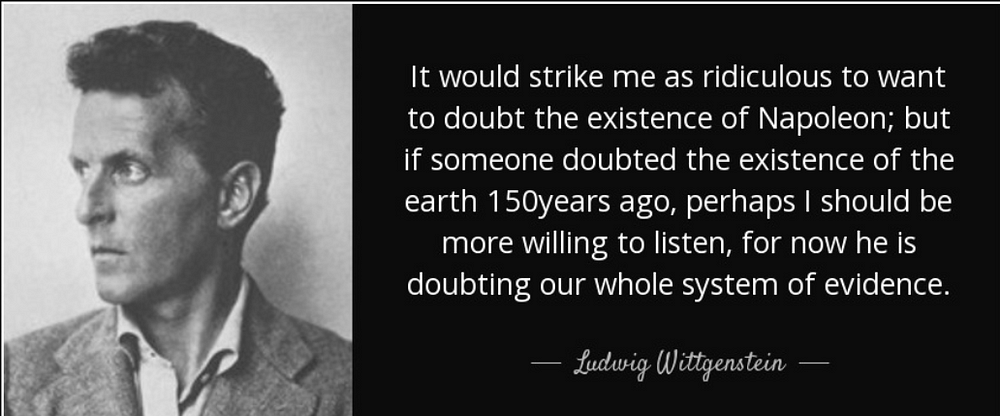

Now take a look at this meme:

There’s an element of truth in the meme above. Personally, I feel like I’m encroaching on sacred territory whenever I comment on physics — especially on string theory. Put simply, I don’t know the maths. Thus, to varying degrees, I must rely on what philosophers call testimony…

Not that any single testimony — even a large scale set — could ever be decisive when its comes to a non-scientist (or a layperson) accepting a scientific idea or theory. After all, the community of physicists itself contains members who often (sometimes strongly) disagree with each other.

And it can’t all be about body counts (i.e., or the “scientific consensus”) either.

The other thing about the meme above is that particle physicists themselves say that other “particle physicists are wrong”. Some physicists say that string theorists are wrong. Indeed, some string theorists say that other string theorists are wrong — at least on details.

So how does a layperson deal with the claims of scientists?

More specifically, how does a layperson deal with statements about string theory, M-theory, the multiverse, the Big Bang, cosmic inflation, dark matter, black holes, etc?

I’ll come clean here…

Again, when it comes comes to mathematical physics generally, I mainly rely on testimony.

Indeed, when it comes to string theory specifically, what else can I rely on other than testimony?…

I’m not a physicist.

I’m not very good at maths.

Sure, I know a bit about physics, and some basic maths. I also know (or I may know) the non-mathematical parts of the physics I comment upon.

But is all that enough?…

Enough for what?

Well, it depends.

So if we take Peter Woit’s own words on string theory again, then I certainly don’t know all the maths or physics. I probably don’t even know 1% of the maths. (This is, of course, an entirely arbitrary percentage.)

So where does that leave me?

Indeed, where does it leave other non-scientists (or laypersons)?

It leaves me (if not all other laypersons) with philosophy of science books and papers, as well as popular-science books and articles.

Again, is that enough?…

All that said, many non-physicists certainly do believe that they have enough knowledge and wisdom to come down strongly in favour (or against) string theory, M-theory, the multiverse, the Big Bang, cosmic inflation, dark matter, black holes, the standard model, etc. (Many non-scientists also have an aesthetic taste for particular interpretations of quantum mechanics.)

Yet surely science mustn’t be the sole preserve of professional scientists.

That said, even after reading many introductions to scientific issues, it’s still very difficult for a non-scientist to come down on any side. Or, rather, it isn’t difficult for some laypersons, but it is for others.

In terms of string theory again.

I personally don’t have a firm scientific position on string theory. I certainly don’t adopt any strict scientific position on it. That’s primarily because any position (at least of a scientific nature) on string theory must — almost of necessity — involve complex mathematics, as well as a deep knowledge of mathematical physics generally…

Yet (as already stated) I’m neither a mathematician nor a physicist.

So where does that leave me?

Where does that leave all non-scientists (or laypersons)?

All that said, it’s also the case that nothing advanced in this essay depends on my knowing the complex mathematics required for any scientific theory. Indeed, everything said should stand (or fall!) without such detailed technical knowledge…

But what, exactly, is testimony?

Wikipedia on the Philosophy of Testimony

Take these introductory remarks on testimony:

“[I]t seems that many of the beliefs that we hold have been gained through accepting testimony. For example, one may only know that Kent is a county of England or that David Beckham earns $30 million per year because one has learned these things from other people.”

Couldn’t it be argued that most (i.e., not many) “of the beliefs that we hold have been gained through accepting testimony”? That said, individuals hold so many beliefs that it would be almost impossible to quantify, and then answer, this question. In any case, the two examples given in the passage above could be added to indefinitely when it comes to the set of beliefs the average person holds.

When it comes to string theory (or any other complex theory from physics), then isn’t (almost?) everything the layperson holds based on testimony?

The quoted passage above continues in the following manner:

“One of the problems with acquiring knowledge through testimony is that it does not seem to live up to the standards of knowledge. As Owens notes, it does not seem to live up to the Enlightenment ideal of rationality captured in the motto of the Royal Society — ‘Nullius in verba (Into the word of no one)’. The Royal Society interprets this as ‘take nobody’s word for it.’"

All this depends on which “standards of knowledge” we have in mind. Perhaps there is no definite article when it comes to the “standards of knowledge”. Or, rather, there may be, but only if we single out (as this writer has done) something like “the Enlightenment ideal of rationality”.

Indeed, we can even question this standard of knowledge (i.e., “take nobody’s word for it”) because it may be impossible to abide by. On a daily practical level, this would certainly be the case. However, even philosophically, it may be too much to ask.

What’s more, if this version of the Enlightenment ideal of rationality is truly an impossible ideal, then in what sense can we call it a definition of (or take on) rationality at all?

In addition and self-referentially speaking, don’t some of us take it on testimony that this Enlightenment ideal of rationality is itself, in fact, a true or worthy ideal? Moreover, is the aim of knowledge (or rationality) really to “take nobody’s word for”… anything? [This was Descartes’ starting point in his Cogito.]

Try it.

Try taking no one's word for anything.

Then see how things turn out.

Thus, this (as it were) radical Enlightenment stance on rationality (or knowledge) may itself need to be accepted on testimony — at least at first.

In any case, the quoted passage from Wikipedia ends with this final question:

“Crudely put, the question is: ‘How can testimony give us knowledge when we have no reasons of our own?’”

Is this correct?

We may have “reasons of our own” for accepting other people’s reasons of their own. After all, accepting only one’s own “word for it” could literally incapacitate us. Thus, knowledge-wise, we’d then possibly be in a worse position than the gullible person who accepts everything everybody says.

Now take Wittgenstein’s case against global scepticism (or against global doubt), and how it can be connected to taking any strong position on testimony.

Wittgenstein on Doubting All Testimony

This is how Ludwig Wittgenstein put matters in his posthumous book On Certainty:

“The questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those [doubts] turn.

“That is to say, it belongs to the logic of our scientific investigations that certain things are in deed not doubted…

“My life consists in my being content to accept many things.”

We can’t doubt anything without exempting certain others things from doubt. Thus, the basic position here is that even philosophical doubt requires belief. In other words, in order to get the game of doubt under way, certain things must be placed beyond doubt.

In terms of testimony itself, that paragraph directly above can now be rewritten in this way:

We can reject (or doubt) a single case of testimony while also exempting many others cases of testimony from doubt.

The basic position here is that even philosophical doubt about certain cases of testimony requires belief about other cases. In other words, in order to get the game of rejecting (or doubting) testimony under way, certain other examples of testimony must be placed beyond doubt.

To give a mundane example.

Say that you’re doubting a friend’s testimony when it comes to (as it were) the facts of geography. You wouldn’t also thereby doubt the very meanings of your friend’s (non-technical) words.

That would be semantic doubt, not geographical doubt.

Similarly, you wouldn’t contemplate the possibility that your friend’s statements about geography are actually coming from a person, rather than from a robot or an evil demon. That would be a doubt about “other minds”, not a doubt about geographical statements.

So what’s at the heart of these “exemptions from doubt” is the “context” in which each case of testimony takes place. As Wittgenstein (again) put it:

“Without that context, the doubt itself makes no sense: The game of doubting itself presupposes certainty.”

“A doubt without an end is not even a doubt.”

If one rejects (or doubts) every case of testimony, then there’s no sense in rejecting (or doubting) any case of testimony. Thus, doubts about particular cases of testimony must occur within the context of belief.

So it’s worth bringing in the American philosopher David Lewis here.

David Lewis on What We Can Properly Ignore

At least within the limited (or strict) domain of epistemology, David Lewis (1941–2001) introduced the notion of what can be “properly ignored”. This is the idea that certain “sceptical possibilities” can be properly ignored if they’re deemed to be irrelevant.

Similarly, one needn’t be sceptical about (or one needn’t question) all cases of testimony.

Strictly speaking, Lewis’s account of the notion of properly ignoring (sceptical) possibilities applies (as with Wittgenstein) only to specific contexts. The following passage is Lewis himself on this matter:

“I may properly ignore some uneliminated possibilities; I may not properly ignore others. Our definition of knowledge requires a sotto voce proviso. S knows that P iff S’s evidence eliminates every possibility in which not-/’ — Psst! — except for those possibilities that we are properly ignoring.”

However, both Lewis himself and other philosophers broadened this notion out to include other cases.

Lewis himself specifically mentioned testimony. He asked his readers the following question:

“What (non-circular) argument supports our reliance on [] testimony?”

Lewis’s point was that Smith’s reliance on testimony (as well as on perception and memory) in the past is believed (by Smith himself) to justify his reliance on testimony in the present…

Yet surely this is a circular position.

In other words, Smith is using his prior reliance on testimony to justify his present reliance on testimony.

What’s more, what if Smith hadn’t even justified his prior reliance on testimony? Would this mean that his present reliance wouldn’t be justified either?

Of course, it might well have been the case that Smith’s prior reliance on testimony was indeed justified. However, do his previous justifications automatically mean that he doesn’t need to (re)justify his present reliance on testimony?…

Psst!

And this is where David Lewis argued that we know certain things even though “we don’t even know how we know”. Or, as Lewis also put it, “justification is not always necessary”.

No comments:

Post a Comment