This essay is about Owen Flanagan’s naturalist account of phenomenology. More specifically, it tackles various phenomenological accounts of how things seem to us. Flanagan is an American philosopher.

Strictly speaking, Flanagan’s use of the word “phenomenology” doesn’t square too well with many other accounts of phenomenology. Particularly, it doesn’t square with those mainly found — to generalise — in continental philosophy.

Flanagan’s usage, instead, is more in tune with the actual etymology of the word - as in this account:

“The term phenomenology derives from the Greek φαινόμενον, phainómenon (‘that which appears’) and λόγος, lógos (‘study’).”

The relevant words in the above are “that which appears”. Indeed, the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl once used the (Cartesian) words “given in direct ‘self-evidence’” when he referred to what he was studying.

Flanagan’s usage, on the other hand, doesn’t strictly abide by the following definition:

“Phenomenology is the philosophical study of objectivity and reality (more generally) as subjectively lived and experienced.”

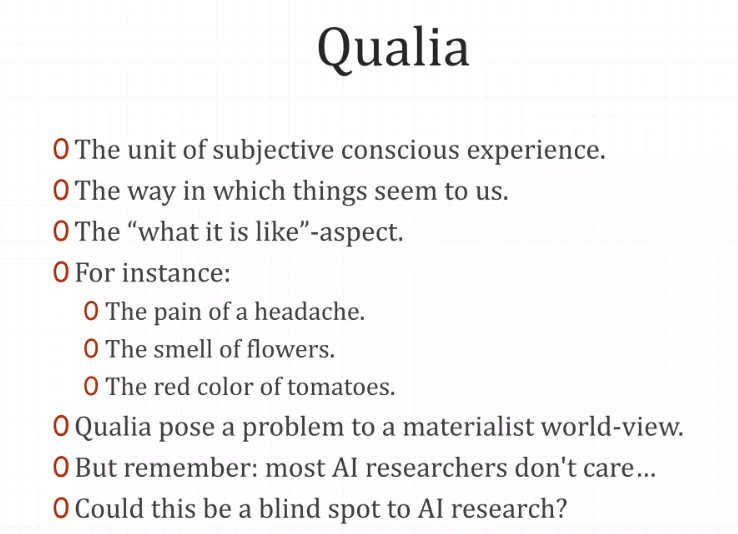

In simple terms. Flanagan’s use of the word “phenomenology” seems to factor out (or simply ignore) “objectivity and reality”. More correctly, Flanagan believes that the qualiaphiles and anti-physicalists he’s arguing against factor out objectivity and reality.

So although Flanagan accepts phenomenology, he’s also a naturalist whose writings are full of scientific detail and case studies. This means that he’s certainly not a phenomenologist in the following sense either:

“Phenomenology proceeds systematically, but it does not attempt to study consciousness from the perspective of clinical psychology or neurology. Instead, it seeks to determine the essential properties and structures of experience.”

As already stated, Flanagan’s position is at odds with what many other philosophers (though not all) have taken phenomenology to be. That said, it’s not being said here that Flannagan actually claims to be a phenomenologist (at least not in any strict sense). Instead, his position is that phenomenology is something that naturalists (such as himself) should take note of, and then tackle.

In basic terms, Flanagan believes that phenomenology is (to ironically rewrite Philip Goff’s words) a datum in its own right.

Against Phenomenology?

Flanagan offers his readers a negative appraisal of phenomenology in the following passage:

“One might nonetheless think [i.e., after reading the arguments in favour of phenomenology] that phenomenology does more harm than good when it comes to developing a proper theory of consciousness, since it fosters certain illusions about the nature of consciousness.”

Indeed, Flanagan also tells us that

“[s]ome philosophers think that phenomenology is fundamentally irrelevant”.

Flanagan then tells us why that’s the case:

“Firstly, there is no necessary connection between how things seem and how they are. Second, we are often mistaken in our self-reporting, including in our reporting about how things seem.”

It’s certainly the case that things seem a certain way (in terms of mental states) to certain human subjects at certain times — or even to all subjects at all times!

Not many philosophers or scientists would deny that.

However, isn’t there often a conflation (or confusion) here between seemings and what actually is the case? (Sure, this is an epistemological minefield, which has been frequently discussed.)

For a start, even a hardcore phenomenologist (or qualiaphile) can’t treat all subjective accounts as gospel because they often contradict each other. However, things still seem a certain way even if those seemings are given contradictory descriptions or accounts. In other words, in all these cases, there was still a way that things seemed…

But who’s denying that?

More relevantly, what work does this acknowledgement of seemings do for the science and ontology of consciousness?

Again, there is indeed a “how things seem”. However, how should we theorise and philosophise about how things seem? In addition, how should we scientifically scrutinise such seemings?

Clearly, we can’t believe that if things seem a particular way, then they must be that particular way.

This is a lesson many students of philosophy learned in their first philosophy class.

In detail.

To subject S, the cricket bat in the water seems to be bent. Yet that doesn’t mean that the cricket bat is actually bent — its light is refracted. Similarly, subject S hallucinating a red goblin is “private to [that] person”. However, we wouldn’t conclude that the red goblin actually exists…

Yet aren’t many people doing something similar to that when it comes to their own seemings? Alternatively, does all this mean that we can’t make mistakes about private conscious (or mental) states?

Yes we can.

Indeed, there’s a large literature on this very subject which tells us that we often do. [See here.]

So why should the case be in different when it comes to phenomenology or the reports of our own subjective states?

It is because they’re (as it’s put) purely internal?

Does that really make a difference?

Well, there may well be a difference between looking at a stick in the water and reporting on one’s own mental state of, say, a pain, or the colour of a rose. However, do many people simply assume that no mistakes can be made about the latter, but they can be made about the former?

Isn’t all this an implicit adoption of the idea of Cartesian infallibility about subjects’ mental states?

No comments:

Post a Comment