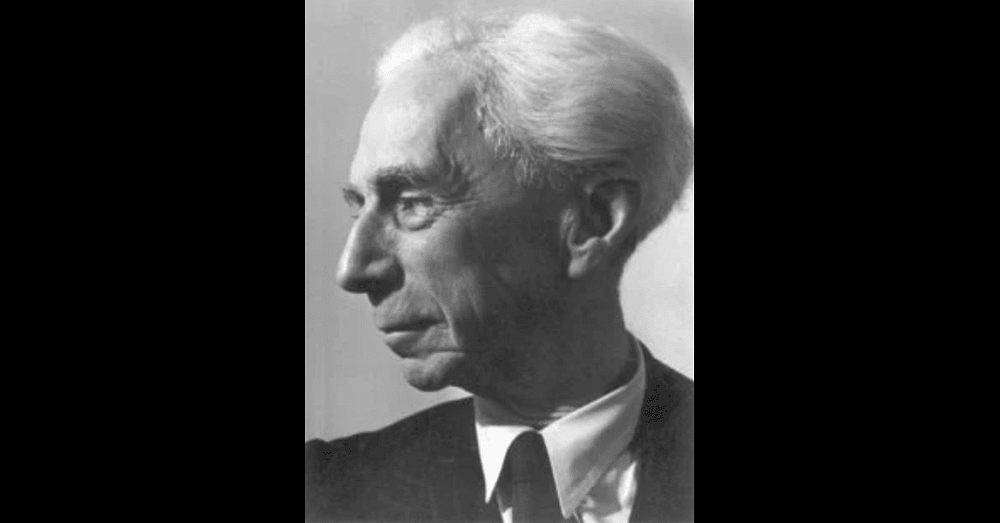

The English philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) believed that when it comes to definitions of the word ‘philosophy’ (as well as to descriptions of the actual practice of philosophy), one can’t help but be metaphilosophical about these issues.

In his Wisdom of the West, Bertrand Russell wrote:

“Definitions may be given in this way of any field where a body of definite knowledge exists. But philosophy cannot be so defined. Any definition is controversial and already embodies a philosophic attitude. The only way to find out what philosophy is, is to do philosophy.”

[As far as I know, Russell never used the word ‘metaphilosophy’, or even the words ‘the philosophy of philosophy’.]

Surely it can said that a definition of the word ‘science’ won’t be as problematic as the word ‘philosophy’. That said, one will also need to take a philosophical stance on what science is (if not on the word ‘science’ itself).

What’s more, would all scientists agree on any single definition?

So let’s rewrite a bit of Russell’s quote above:

The only way to find out what science is, is to do science.

Thus, it can’t be the case that simply because the word ‘philosophy’ is about philosophy that all definitions will be more problematic (or controversial) than definitions (or descriptions) of science.

It can now be said that this controversy (or problem) is also the case with the definitions of many other (philosophically-loaded) words and terms… That’s unless one simply stipulates what a word means: This is how this dictionary defines the word x.

Despite saying all that, the analytic approach to philosophy, for example, certainly (to reuse Russell’s words) “embodies a philosophic attitude”, and that attitude is “controversial”. The same can be said of deconstruction, phenomenology, structuralism, etc. — i.e., virtually any way of doing philosophy will induce some controversy. (Here readers must distinguish positions within philosophy from positions on philosophy itself.)

A Priori Philosophy

It’s hard to grasp Russell’s final sentence in the quote above. Namely: “The only way to find out what philosophy is, is to do philosophy.”

Surely there can’t be such a thing as a priori philosophising.

[The term a priori is used loosely, not technically, in what follows.]

What would a philosophical a priori be like? A philosophy untouched by other philosophies — untouched by other philosophical texts?

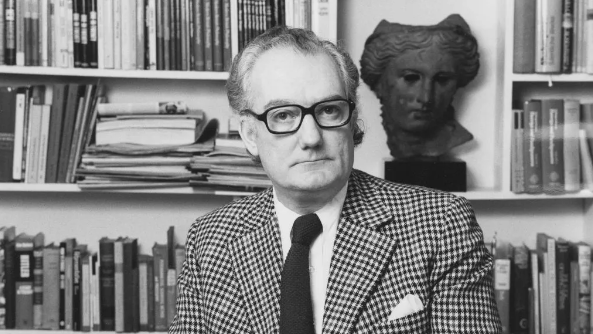

Yet take the British broadcaster and populariser of philosophy, Bryan Magee, and his account of his very own ex nihilo philosophising:

“Until I went to university it never entered my head to associate any of these [philosophical] questions with the word ‘philosophy’. [] I discovered that this is what they were. [] I had grown up a natural Kantian. [] I discovered [] that I had been immersed in philosophical problems all my life.”

[From Magee’s Confessions of a Philosopher: A Journey Through Western Philosophy.]

What a strange passage that is.

Magee wasn’t claiming to be “outside language”: he was claiming to have been outside philosophy. More clearly, he was claiming that all of us — or perhaps only some of us — are born with a quasi-Chomskian Philosophy Faculty. However, if Magee wasn’t claiming something about a universal Philosophy Faculty, then Magee must have been making a claim about himself — and himself alone. That claim must therefore be that Magee was somehow destined to philosophise in the particular manner in which he did in fact philosophise.

Why?

Simply because who Magee was as a human individual.

If the first option is taken (i.e., the quasi-Chomskian Philosophy Faculty), then many — if not all — young children (throughout the world) would be asking the same questions which Magee asked himself when he was a young child.

It’s of course the case that many children do ask philosophical questions.

So which questions was Magee talking about?

As Magee put it, he asked himself questions which he later realised were Kantian, Schopenhauerian, Leibnizian and Wittgensteinian in nature. Yet if that were the case, then why weren’t Kantian and Leibnizian — never mind Wittgensteinian — problems raised years before the birth of these particular philosophers? In addition, if these questions and problems are so natural (Magee himself claimed to be a “natural Kantian”), then why were they certainly not asked in other cultures and at other times?

There may indeed be certain philosophical givens. (The American philosopher Thomas Nagel — in his book The Last Word — believes this to be the case.) Nonetheless, they certainly aren’t, say, Kantian or Wittgensteinian givens. And any any such givens (uncovered by empirical research) tend to be more religious or spiritual in nature, rather than being (strictly speaking) philosophical.

It’s of course possible that Magee was an incredible genius who not only came to Kantian questions and problems without the help of Kant’s own oeuvre, but to Leibnizian and Wittgensteinian problems and questions without their help either!

In the end, it will be empirical and historical research which will determine whether or not Kantian, Leibnizian, etc. problems and questions are really part of the philosophical a priori. From my own knowledge and reflections, I strongly suspect that they aren’t.

If we return to Russell’s opening words.

Firstly, students of philosophy (i.e., not only in universities) read the books of certain philosophers, and only then do they write about the things they too have written about. Such students may even adopt the prose styles of those philosophers. Later, they’ll probably make a self-conscious attempt to write a certain kind of philosophy in a certain kind of way.

However, if such novices didn’t do all that, then isn’t it likely that they’d be doing stream-of-consciousness expressionism rather than philosophy? Unless, again, they’re literally writing (or doing) genuine a priori philosophy.

So in no way will the novice simply discover his own voice the first few times he writes philosophy.

Sure, in order to (as Russell himself put it) “find out” if one can do philosophy, one will need to “do philosophy”. And then one will discover which approach one likes. However, an original position can’t come about simply as a result of doing philosophy.

No comments:

Post a Comment