This essay is a response to ‘Emergence’, by the American theoretical physicist Anthony Garrett Lisi. Lisi argues for something he calls “natural emergence”. The argument which follows is that natural emergence won’t be deemed to be “true emergence” (i.e., strong emergence) by self-styled “anti-reductionists”, or by the religious/spiritual critics of “the pretensions of science”.

(i) Is Love the Timely Mutual Squirt of Oxytocin?

(ii) Natural Emergence

(iii) Laplace’s Demon and Reductionism

(iv) Is Natural Emergence a Numbers Game?

(v) Standard Scientific Emergence

(vi) Conclusion

Is Love the Timely Mutual Squirt of Oxytocin?

The theoretical physicist Anthony Garrett Lisi states that

“romantic love is the timely mutual squirt of oxytocin”.

Surely that’s an outrageous view.

Isn’t this “reductionism gone mad”?

Isn’t Lisi defiling the flower of romantic love in the name of grubby science?…

Actually, the statement above isn’t Lisi’s own position. He wrote the following words:

“To describe romantic love as the timely mutual squirt of oxytocin trivializes the concerted dance of more molecules than there are stars in the observable universe.”

So is that any better?

To the the self-styled “anti-reductionist”, it won’t be.

After all, Lisi has simply moved from talking about oxytocin to talking about “more molecules than there are stars in the observable universe”. This means that Lisi hasn’t moved from talk of oxytocin to talk of something “truly emergent” (or to something “beautifully mysterious”).

The problem here is that one molecule is a natural phenomenon.

And so too are “more molecules than there are stars in the observable universe”.

Of course, Lisi would argue that boiling romantic love down to the “mutual squirt of oxytocin” is far too simplistic. However, Lisi’s complexified picture still won’t take us from the natural to the mysterious, or from the natural to the (to use capitals) Truly Emergent.

So would anyone actually state that “romantic love is the timely mutual squirt of oxytocin”?

Well, molecular biologist, biophysicist and neuroscientist Francis Crick came close to doing so in a passage that’s been (negatively) quoted a million times.

In The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul (1994), Crick wrote the following passage:

“‘You’, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”

In another essay, I argue that it’s easy to believe that Crick was actually being wilfully provocative and rhetorical here. At the same time, he may also have been telling the truth — if only to a degree.

Let’s put (what I take to be) Crick’s central position in this simple way.

If it weren’t for the brain (or if it weren’t for the “nerve cells” mentioned by Crick himself), it would indeed be the case that we wouldn’t have (to use Crick’s own words) “memories, ambitions, personal identity, free will, sorrows”. And we wouldn’t have Lisi’s “romantic love” either.

All these things do depend on the brain.

Isn’t that blatantly obvious to most — i.e., not all — people?

Now does it follow from this that romantic love, joys, sorrows, memories, ambitions, personal identity (taken individually) are identical to a group of neurons, a part of the brain, or even the entire brain taken “holistically”?

Not really.

Perhaps in Lisi’s terms, romantic love, sorrows, memories, ambitions, and personal identity arise from nerve cells. However, they can never be identical to them. Thus, if there’s no identity here, then there can’t be reduction either.

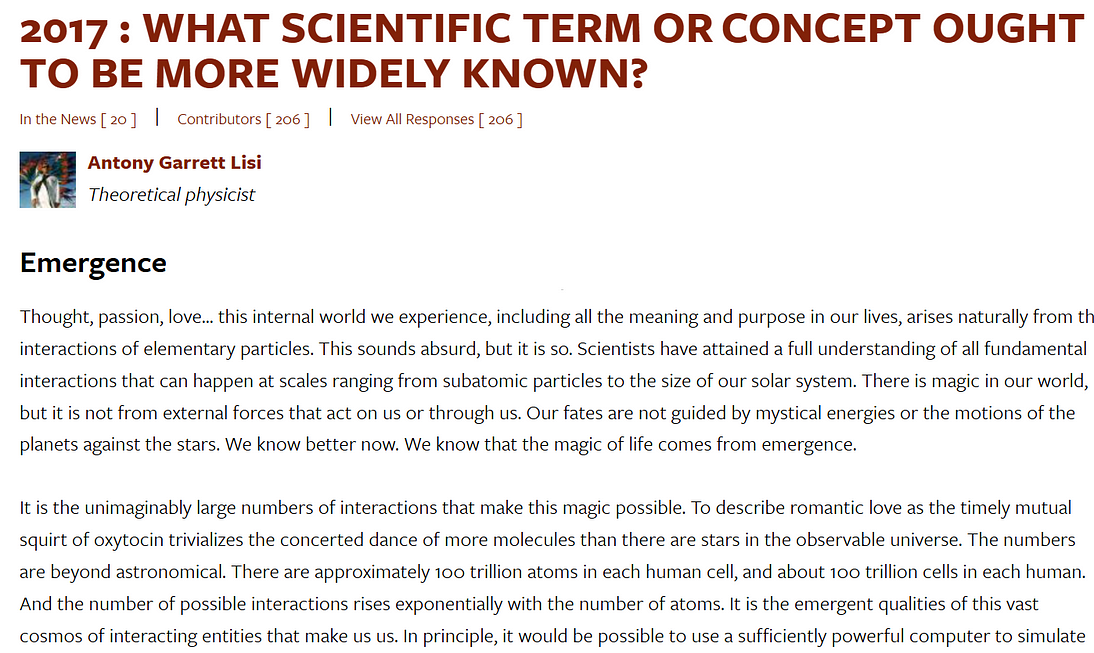

Natural Emergence

Anthony Garrett Lisi happily admits that there is (scientific) emergence — in many cases! (Sabine Hossenfelder also states that “[t]here are lots of emergent properties in physics”.) However, there’s nothing mysterious, supernatural or non-natural going on in any of these cases. Lisi writes:

“There is magic in our world, but it is not from external forces that act on us or through us. Our fates are not guided by mystical energies or the motions of the planets against the stars. We know better now. We know that the magic of life comes from emergence.”

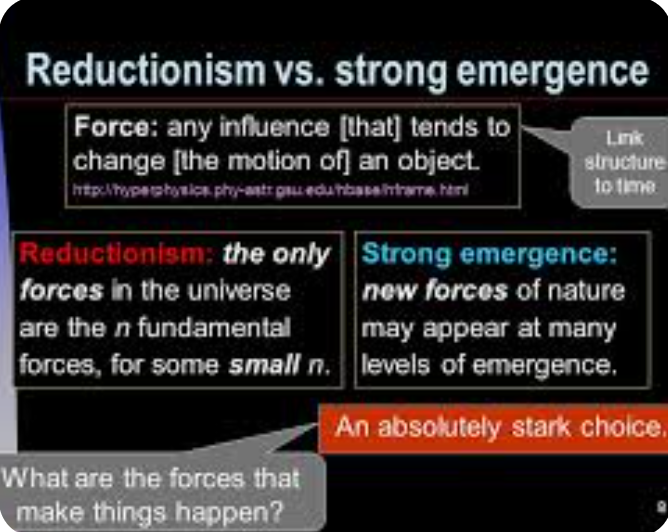

But does Lisi believe in True Emergence (i.e., strong emergence)?

Are his examples of emergence sexy enough?

Lisi’s central point is that emergence is what he calls “natural”. It is never an example of supernatural (or non-natural) “magic”. In other words, Lisi completely accepts the reality (or existence) of emergent phenomena. However, his natural[istic] emergence still wouldn’t please (or emotionally satisfy) the anti-reductionists or those religious critics of “the pretensions of science”.

So what is Lisi’s precise position?

He lays his cards on the table in the following manner:

“Thought, passion, love [ ] this internal world we experience, including all the meaning and purpose in our lives, arises naturally from the interactions of elementary particles. This sounds absurd, but it is so.”

That seems pretty uncontroversial to me. It may even be uncontroversial to anti-reductionists, and to the religious/spiritual critics of science. After all, note the important words “arises [ ] from”. This means that Lisi isn’t claiming that “[t]hought, passion, love” are equal — or identical — to “the interactions of elementary particles”. Again, he’s saying that they arise from such things.

Indeed, Lisi even accepts that “qualitatively new properties” arise from such interactions of elementary particles.

So why does Lisi’s position (in his own words) “sound[] absurd” at all?

Again, where’s the controversy here?

In terms of logical possibility, can’t even the mysterious (or what Lisi calls “the mystical”) arise from the interactions of elementary particles — or from the natural when more generally construed?

Perhaps anti-reductionists and the religious/spiritual critics of science don’t want to tie the Truly Emergent to the natural in any way whatsoever. Indeed, perhaps they believe that even the argument that love, consciousness, etc. arise from the natural still defiles these things.

All that said, if religious/spiritual critics of science and anti-reductionists actually believe in emergence, then surely they must also believe that even the mysterious must emerge from the natural. If this weren’t the case, then how is this any kind of emergence at all?

In terms of examples. If we really have what Lisi calls “mystical energies”, the reality of astrology, an immortal soul, etc., then do we need emergence at all? Surely these things don’t arise (or emerge) from anything — at least not anything natural or scientific.

I’ve mentioned anti-reductionists and the religious/spiritual critics of science because Lisi (obliquely) does so too… Or at least he wrote the following words:

“There is magic in our world, but it is not from external forces that act on us or through us. Our fates are not guided by mystical energies or the motions of the planets against the stars. We know better now. We know that the magic of life comes from emergence.”

Lisi also writes:

“The ladder of emergence precludes the necessity for any supernatural influence in our world.”

Now I’m not saying that all anti-reductionists and the religious critics of science believe in mystical energies or astrology. However, Lisi did broach these alternative views. And he also mentions “supernatural influence”.

As already stated, Lisi believes in natural emergence. He even accepts that “human goals, meaning, and purpose” are examples of this phenomenon. However, his qualification (if that’s what it is) may not appeal — again — to anti-reductionists or to the religious/spiritual critics of science. After all, Lisi writes:

“[H]uman goals, meaning, and purposes exist as emergent aspects in psychology favored by natural selection.”

So, sure, there’s emergence alright. However, Lisi’s particular examples are emergent aspects in psychology favored by natural selection.

That said, would anti-reductionists or the religious critics of science necessarily deny that True Emergence could be a result of aspects in psychology favored by natural selection? After all, isn’t it at least possible that the mysterious (or at least the non-reducible) may emerge from the natural? Indeed, can we have these natural “aspects” (or groundings), and still have True Emergence?

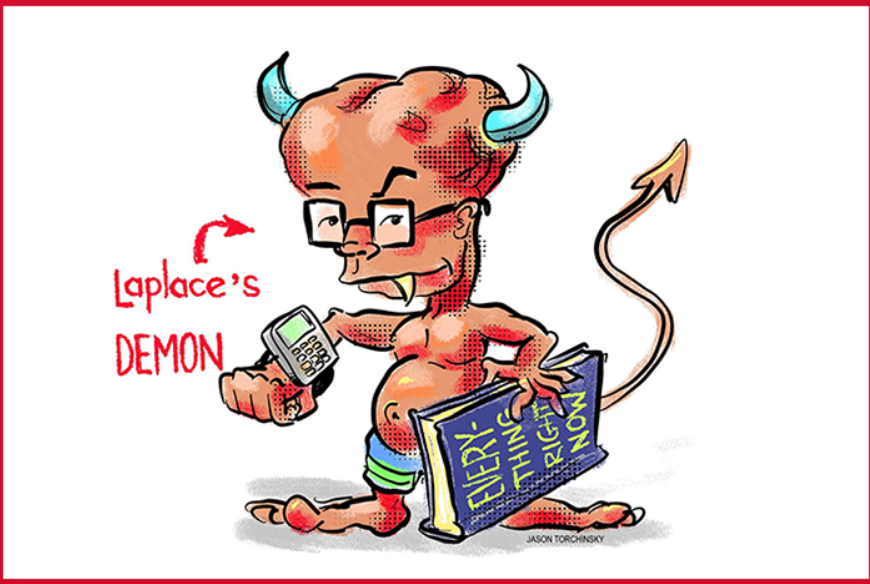

Laplace’s Demon and Reductionism

There are problems with Lisi’s view of emergence.

For example, he writes:

“In principle, it would be possible to use a sufficiently powerful computer to simulate the interactions of this myriad of atoms and reproduce all our perceptions, experiences, and emotions.”

That, again, may seem like reductionism gone mad. However, Lisi himself continues with the following words:

“But to simulate something does not mean you understand the thing — it only means you understand a thing’s parts and their interactions well enough to simulate it.”

Of course, a simulation isn’t literal physical replication.

So this is largely dependent on how we define Lisi’s word “simulate”.

How would a simulation (or model) of “a thing’s parts and their interactions” actually “reproduce all our perceptions, experiences, and emotions”?

Again, such a simulation (or model) could reproduce such things in the sense that it… well, simulates (or models) them. However, we wouldn’t have a physical — or otherwise — replication of “the interactions of this myriad of atoms”. In crude terms, then, we wouldn’t be doing the equivalent of teleportation as found in the Star Trek series.

Lisi himself kinda plays down his simulations in that he sees them (or sees their failings) in terms of human understanding. As already quoted:

“[T]o simulate something does not mean you understand the thing.”

Lisi believes that by simulating (or modelling) “a thing’s parts and their interactions”, you don’t thereby understand it.

Why not?

Is it because the simulation actually leaves out all the emergent properties?

At least that seems to be Lisi’s argument.

However, why can’t emergent properties be simulated (or modelled) too?…

Is it because simulations (or models) leave out emergent properties — by definition?

Why would that be the case?

Perhaps it’s because emergent properties are deemed to be over and above the interactions of this myriad of atoms.

Is Natural Emergence a Numbers Game?

In a couple of places, Lisi talks about the huge number of atoms or molecules which give rise to emergent properties.

To Lisi, then, emergence sometimes seems to be a numbers game.

For example, Lisi writes:

“When the number of parts becomes huge, such as for atoms making up a human, analysis is practically useless for understanding the system — even though the system does emerge from its parts and their interactions.”

Lisi also tells us that emergence is the

“cumulative side-effects of interactions of large numbers of constituents that result in qualitatively new properties that are best understood within the context of the new level”.

So is emergence — even strong emergence — really a numbers game?

Crudely, if we have 1000,000 atoms and nothing emerges, do we actually need 1000,001 atoms in order for an emergent property to arise?

This question may be unfair because Lisi states that “analysis is practically useless for understanding [a] system” which involves a “huge number of parts”.

So is this an epistemic — i.e., not an ontological — problem? That is, is it simply the case that we don’t have the means to analyse such huge numbers of parts?

However, forget analysis and large numbers for a moment: is emergence — regardless of our analyses or knowledge — really just a question of large numbers of parts?

So forget “understanding the system” too: do large numbers — on their own — really bring about emergent properties?

Standard Scientific Emergence

Lisi offers his readers a fairly standard account of emergence when he writes the following words:

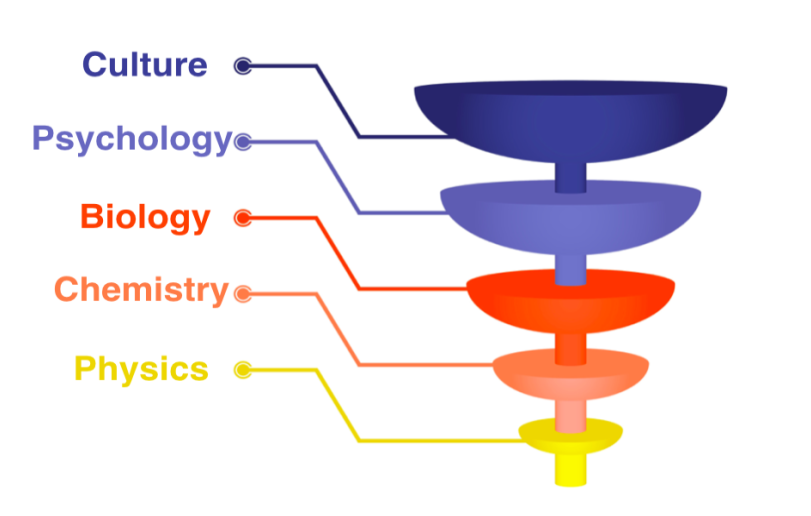

“Atomic physics emerges from particle physics and quantum field theory, chemistry emerges from atomic physics, biochemistry from chemistry, biology from biochemistry, neuroscience from biology, cognitive science from neuroscience, psychology from cognitive science, sociology from psychology, economics from sociology, and so on.”

The above seems very simple and fairly conventional.

Lisi continues:

“This hierarchical sequence of strata, from low to high, is not exact or linear — other fields, such as computer science and environmental science, branch in and out depending on their relevance, and mathematics and the constraints of physics apply throughout.”

But what about emergence?

Lisi then emphasises the practical and epistemic limitations of analysing chemical phenomena with the exclusive tools of physics. He goes on:

“But the general pattern of emergence in a sequence is clear: at each higher level, new behavior and properties appear which are not obvious from the interactions of the constituent entities in the level below, but do arise from them.”

That’s the overall picture.

In terms of an actual example, Lisi writes:

“The chemical properties of collections of molecules, such as acidity, can be described and modeled, inefficiently, using particle physics (two levels below), but it is much more practical to describe chemistry, including acidity, using principles derived within its own contextual level, and perhaps one level down, with principles of atomic physics. One would almost never think about acidity in terms of particle physics, because it is too far removed.”

All that squares perfectly well with the positions of the theoretical physicist Murray Gell-Mann. He seemed to strike a middle-way between strong and weak emergence. Here’s his hint at strong emergence:

“Here, much more than in the case of nuclear physics, condensed matter physics, or chemistry, one can see a huge difference between the kind of reduction to the fundamental laws of physics that is possible in principle and the trivial kind that the word ‘reduction’ might call up in the mind of a naive reader. The science of biology is very much more complex than fundamental physics because so many of the regularities of terrestrial biology arise from chance events as well as from the fundamental laws.”

Then Gell-Mann also hints at both weak and strong emergence:

“Even though in principle those laws can be derived from the level below plus a lot of additional information, the reasonable strategy is to build staircases between levels both from the bottom up (with explanation in terms of mechanisms) and from the top down (with the discovery of important empirical laws). All of these ideas belong to what I call the doctrine of ‘emergence’.”

Interestingly enough, the American biologist and naturalist E.O Wilson (a man who’s often been accused of “reductionism”) expressed a similar view in the following:

“Major science always deals with reduction and resynthesis of complex systems, across two or three levels of complexity at a step. For example, from quantum physics to the principles of atomic physics, thence reagent chemistry, macromolecular chemistry, molecular biology, and so on — comprising, in general, complexity and reduction, and reduction to resynthesis of complexity, in repeated sweeps.”

The upshot here is that we could have a reduction in principle, just not in practice. So there’s nothing spooky or magical going on here — not even when it comes to consciousness.

Conclusion

Anthony Lisi uses the term “emergence” (or “emergent”) in such a broad way that (to be slightly rhetorical) almost everything that’s not described by fundamental physics is deemed to be an example of emergence. Indeed, in Lisi’s own book, “the side-effects of interactions of large numbers of constituents” all result in cases of emergence.

This isn’t an incorrect use of the word “emergence”. It’s just very broad.

More relevantly, even Lisi’s references to qualitatively new properties may not be enough for anti-reductionists, or for those religious critics of “scientific reductionism” who want their emergent properties to be mysterious and completely untouchable by science.

No comments:

Post a Comment