|

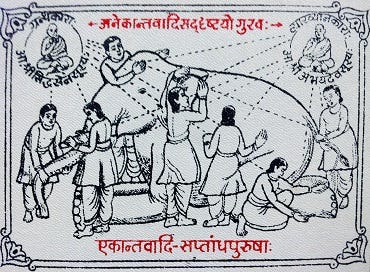

| Top image: the symbol of Jainism. |

Contents:

i) John Barrow’s Translation of Jaina Seven-Valued Logic

ii) The Seven Values of Jaina Logic

iii) On Accepting Inconsistent Scientific Theories

iv) Graham Priest’s Boundary

v) A & ¬A: Epistemic or Ontological?

vi) Conclusion: The Philosophy of Jaina and Dialethic Logics

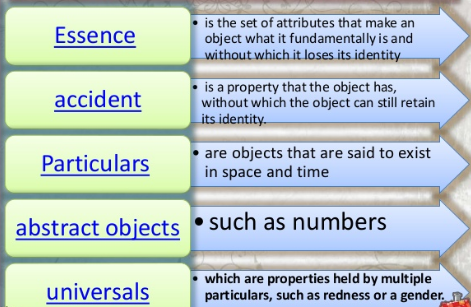

Jaina seven-valued logic was first developed by Jain philosophers in ancient India. These seven different values have actually been taken to be different truth values. They’ve been taken that way primarily because the sentences which express them can be seen as the expressions of different truth values (e.g., “Arguably, it exists” or “Maybe it is indeterminate”).

This Jaina system of truth values is referred to as syādvāda. The earliest reference to syādvāda can be found in the writings of Bhadrabahu (c. 367 — c. 298 BC).

Jaina seven-valued logic has also been taken to support a religious and philosophical “theory of pluralism”. That ties in with this piece’s stress on epistemology, rather than on ontology. That is, giving an epistemological and religious (in the case of Jainism) stress on pluralism can be seen in contemporary philosophical terms as both stressing logical pluralism and the indeterminate (or undecided) nature of our epistemic positions. (This logical pluralism isn’t about different logics in the plural; but a plurality of truth values within a given system of logic.)

So what about dialetheism?

Dialetheism is the view that there are statements (or propositions) which are both true and false. In more detail, dialetheism has it that there can be true statements whose negations (see final section) are also true. The philosopher and dialethic logician Graham Priest defines dialetheism as the view that there are “true contradictions” (or dialetheia).

Now of course it’s not wise to create a (logical) equivalent of Fritjof Capra’s book The Tao of Physics by artificially squeezing dialethic logic into Jaina logic (or vice versa). However, since Graham Priest himself (as a dialethic logician) is well aware of Jaina logic, this may not be such a bad thing. So perhaps it can be said that dialetheism’s philosophical and logical positions are similar to some (or all) of the Jaina values.

More specifically to this piece, Priest stresses (as will be shown later) the acceptance of inconsistent logical systems and scientific theories by logicians and scientists — and that itself can be seen as as a kind of logical and theoretical pluralism.

The dialethic position on truth is also similar to that of the Jaina principle anekānta (“many-sidedness”). This school of Jaina philosophy also used the word naya; which is sometimes translated as “the partial expression of the truth”. In addition, in Buddha’s Middle Way the answers “it is” and “it is not” (to any given — philosophical? — question) are seen to be too extreme. Indeed, like dialetheism, Mahāvīra taught people to accept that A (i.e., a given state of affairs) both “is” and “is not” — or at least that people should acknowledge that “maybe” (see next section) A both is and is not.

John Barrow’s Translation of Jaina Seven-Valued Logic

I first came across a reference to Jaina seven-valued logic in a book by the cosmologist, theoretical physicist and mathematician John D. Barrow. This reference is in the form of a note in Barrow’s book Pi in the Sky.

It turned out that Barrow’s version (or translation) of those seven values is expressed in a way which is a little unlike some of the other translations which can be found (as will become clear later). Still, Barrow’s version (or translation) has the virtue of simplicity.

Barrow introduces the seven values in this manner:

“In a non-Western culture like that of the Jains in ancient India one finds a more sophisticated attitude towards the truth status of statements. The possibility that a statement might be indeterminate is admitted as well as the possibility that uncertainties exist in our analysis. These would correspond to statistical statements in which we simply give the likelihood that a certain statement is true or false. Jaina logic admits seven categories for a statement which reflect both its intrinsic uncertainty and the incompleteness of our knowledge of it.”

He then both numbers and translates the Jaina values:

(1) maybe it is;

(2) maybe it is not;

(3) maybe it is, but it is not;

(4) maybe it is indeterminate;

(5) maybe it is but is indeterminate;

(6) maybe it is not but is indeterminate;

(7) maybe it is and it is not and is also indeterminate.

The first mention of Jaina seven-valued logic dates back to c. 433–357 BC; which is also roughly 40 years before the birth of Aristotle. Yet it can be argued that a many-valued logic was seen in Western culture before the 20th century. After all it was Aristotle (384–322 BC) himself who first recognised the reality of statements with indeterminate truth values. (The sorites also date back to the ancient Greeks.) Still, Aristotle’s indeterminate “future contingents” particularly refer to future states of affairs, not to present ones (as is the case with Jaina values).

In any case, come the 20th century there was a host of many-valued logics on offer in the West. And it can be argued that some positions within them restate (if in new ways) the seven values of Jaina logic.

The obvious point to make about the seven values of Jaina logic is that they don’t include the words true and false. Initially this seems odd when considering the fact that they’re taken to be truth values. Indeed not even (1) (“maybe it is”) and (2) (“maybe it is not”) can really be taken to be translations of true and false. The main reason for this is that every expression begins with the word “maybe” — and clearly that makes all the difference.

Dialetheic logic, on the other hand, does accept and use the values true and false, even if it places them together in a conjunction of contradictions: namely, A & ¬A. (Other 20th century logics had three — or more — truth values.)

If we return to the “maybe” of Jaina logic.

The Sanskrit doctrine of naya is the idea that there are many partial perspectives of any given p (statement/proposition) or A (state of affairs), and none of which can be taken as containing the whole truth. More broadly, Jaina seven-valued logic has been taken to support a “theory of pluralism” (see anekāntavāda). So, clearly, the word “maybe” is essential for all seven values of Jaina logic. And, later, it will be argued that it is — at least in part — a normative use of the word “maybe”.

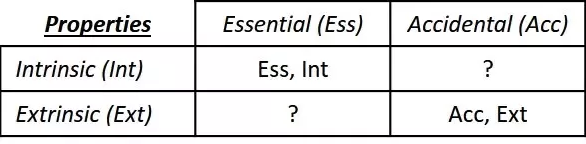

The other point worth making is that it’s been argued that there are only really three (not seven) basic values in Jaina logic: namely, true (T), false (F) and unassertible (U). These words are simplifications of (1) to (3) above. Yet surely the basic values are actually “maybe it is”, “maybe it is not” and “maybe it is indeterminate” (or “maybe it is unassertible”), not true, false and indeterminate. This means that the seven values of Jaina logic seem to intentionally steer us away from the words true and false (for the epistemic, normative and pluralist reasons already mentioned).

In any case, the argument is that (4), (5), (6) and (7) are a combination of (1), (2) and (3). That is, (1), (2) and (3) produce TF (true and false), TU (true and unassertible), FU(false and unassertible), and TFU (true, false and unassertible). But, as already stressed, the words “true” and “false” shouldn’t be used at all as translations of the Jaina values. And, again, the main reason for this is down to the modifier “maybe” (i.e., syat in the Sanskrit).

The Seven Values of Jaina Logic

As expressed (or translated) by John Barrow (though not as expressed or translated elsewhere), Jaina seven-valued logic is about statements (e.g., Barrow writes “seven categories of statement”); which in the following (though not in Barrow’s translation) are symbolised by the letter p. The following sentences can also be taken to be about a possible (or actual) state of affairs; as symbolised by the letter A.

So let’s take each expression of Jaina values one at a time:

(1) Maybe it is.

In terms of a proposition (or statement):

Maybe p is true.

Or:

It is possible that p is true; though we don’t know that p is true. [In modal logic: ◇p.]

In terms of a state of affairs:

Maybe A is the case.

The above is epistemic in nature because it’s saying that maybe A is the case; though we don’t know that A is actually the case. [◇A]

(2) Maybe it is not.

Everything said in (1) above can now be said about (2). In this case, we simply substitute the words “is the case” with the words “is not the case”. (Or, in terms of p, we can substitute the words “is true” with “is false”.)

(3) Maybe it is, but it is not.

This is a difficult one to decipher. In propositional terms, we have: Maybe p is true; but p is not true.

Or: Possibly p is true; but p is not true. [◇p]

In terms of a state of affairs: Maybe A is the case, but A is not the case.

To translate again:

Maybe A could possibly be the case. However, A is not the case. [◇A]

So it’s not being claimed that A “is not”. The idea is that it’s possible that A is not. The point being that we don’t know if A is or is not the case. In epistemic terms, we may well have good reasons to believe that A is the case. However, it still could be be that A is not the case. This means that, as yet, we haven’t enough information to establish that A actually is the case. And because of that, it’s still possible that A is not the case.

(4) Maybe it is indeterminate.

To discuss this in terms of propositions (or statements), that means that, as yet, we can’t decide whether p is true or p is false. In other words, p’s truth value is undecided or indeterminate. So does p have a truth value if its value is undecided or indeterminate? (That raises questions which can be found in the realism vs. anti-realism debate.) As it is, one can argue that if p is indeterminate, then it can’t have a truth value — that is unless indeterminate itself is a truth value (as with “non-assertible” later).

On the other hand, epistemically p may not have its truth value “given to it” (or established) by persons; though, in (ontologically) realist (or platonic) terms, it may still be either true or false.

(5) Maybe it is but is indeterminate.

This is difficult to grasp. It is, however, similar to (4) above. That is, p may be true. However, as yet p’s truth (or A being the case) is indeterminate to the speaker or theorist. p could have a truth value; though we don’t know its truth value. Similarly, A may be the case; though we don’t know whether A is the case.

(6) Maybe it is not but is indeterminate.

This is the same as (5) above except that it it raises the possibility of p’s falsehood (or A not being the case).

(7) Maybe it is and it is not and is also indeterminate.

This is the most difficult to comprehend of all seven Jaina values. It appears to embrace a dialethic position in that it is an acceptance that A both is the case and that A is not the case. However, the modifier “maybe” changes everything.

The question is: How does the final clause “and is also indeterminate” change — or add to — (if at all) the opening clause “maybe it is and it is not”? Does this mean that p is indeterminate simply because we don’t know whether it is true or false? Or is it indeterminate because it is both true and false? However, if we know that it is both true and false, then how can it be indeterminate? In other words, it can be a determinate matter that p is both true and false.

So can a contradiction really be determinate? And how is both the truth and falsity of p established?

With (7) we have an ostensibly ontological statement (or opening clause). That is, the phrase “maybe it is and it is not” seems to be telling us that maybe p is both true and false. Therefore (surely) something about the world must make it both true and false.

It could be, however, that the phrase “maybe it is and it is not” is not ontological at all. It could simply be saying not that A both is and is not the case; but that for all we know A may be the case, or A may not be the case. (Alternatively, maybe p is true or maybe p is false.)

So now here’s the other translation (mentioned earlier) of the seven values of Jaina logic:

(1) Arguably, it [that is, some thing] exists. [Syad asty eva.]

(2) Arguably, it does not exist. [Syan nasty eva.]

(3) Arguably, it exists; arguably, it doesn’t exist. [Syad asty eva syan nasty eva.]

(4) Arguably, it is non-assertible. [Syad avaktavyam eva.]

(5) Arguably, it exists; arguably, it is non-assertible. [Syad asty eva syad avaktavyam eva.]

(6) Arguably, it doesn’t exist; arguably, it is non-assertible. [Syan nasty eva syad avaktavyam eva.]

(7) Arguably, it exists; arguably, it doesn’t exist; arguably it is non-assertible. [Syad asty eva syan nasty eva syad avaktavyam eva.]

As stated earlier, in the translation (or version) directly above, Jaina seven-valued logic is a set of sentences about a thing (or an “object”), not about statements (or propositions). Thus, in that simple sense, this is ontology, not logic or epistemology. Having said that, virtually everything said about statements (or propositions) can now be said about these statements about a thing. Moreover, Barrow’s own translation (or version) can also be read as to be about things, not about statements. (Barrow himself says they are about “statements”.) And since the following seven translations state such things as “arguably, it is non-assertible”, then they too can be read as being about statements, not about a thing (though they’re still statements about a thing). Or, more precisely, (1) to (3) are ontological in nature; and (4) to (7) are epistemic (e.g., they use the phrase “non-assertible”). As for the term “non-assertible” in the above, it is equivalent to Barrow’s word “indeterminate”.

There’s not really much more one can add to this translation or version. Nonetheless, the modifier “arguably” seems to stress — even more so than the word “maybe” — the epistemic nature of these seven values. Put simply, one can argue that some object (or thing) either “exists” or that it “does not exist”. Or, more epistemically, the claim “x exists” is “non-assertible”; as is the claim “x does not exist”. That is, as yet, the theorist has no epistemic right to assert that either “x exists” or that “x does not exist”.

On Accepting Inconsistent Scientific Theories

Professor Bryson Brown (in his paper ‘On Paraconsistency’) states the importance of inconsistency for dialetheism. (He also says that dialetheists are “radical paraconsistentists”.) He writes:

“[Dialetheists] hold that the world is inconsistent, and aim at a general logic that goes beyond all the consistency constraints of classical logic.”

Brown continues by saying that dialetheists “view these paradoxes as proofs that certain inconsistencies are true”… But true of what? True only of the paradoxes themselves or true of the world? (Of course the paradoxes also exist in the world — if in an abstract or platonic world.)

So what about Graham Priest’s position on consistency? He writes:

“[W]e all, from time to time, discover that our views are, unwittingly, inconsistent.”

When discussing the virtue of simplicity, Priest also asks the following question:

“If there is some reason for supposing that reality is, quite generally, very consistent — say some sort of transcendental argument — then inconsistency is clearly a negative criterion. If not, then perhaps not.”

As dialethic logicians have stated, we can accept inconsistent scientific theories if they still prove to be useful and have predictive consequences. In fact scientists (especially physicists) have been fine with this situation for a long time. Priest puts it this way:

“Inconsistent theories may have physical importance too. An inconsistent theory, if the inconsistencies are quarantined, may yet have accurate empirical consequences in some domain. That is, its predictions in some observable realm may be highly accurate. If one is an instrumentalist, one needs no other justification for using the theory.”

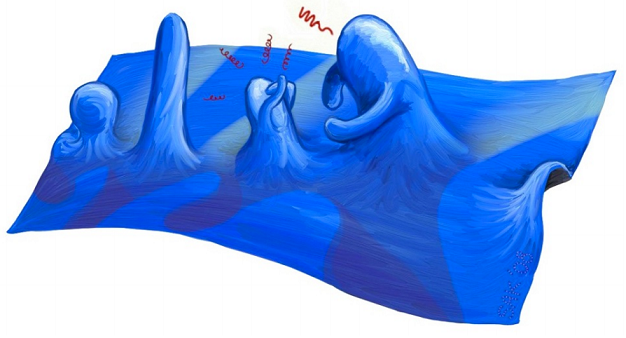

Bryson Brown also says that

“our best theory of the structure of space-time, Einstein’s general theory of relativity, is inconsistent with our quantum-mechanical view of microphysics”.

Brown also mentions the Danish quantum physicist Niels Bohr within this context. So did Bohr believe that there were inconsistencies — let alone contradictions — actually in the world? Philosophers have disagreed on this. However, it can be argued that Bohr might have found it difficult to grasp what an inconsistent world (or any aspect of the world) would — or could — be like. This is at least the case when it comes to worldly contradictions. That is, it is hard to see how [A & not-A] can be the case at one and the same time. So this means that we need to decide if embracing theoretical inconsistencies (in science, logic, etc.) also means embracing worldly contradictions.

Bryson Brown also acknowledge the fact that, in general, we “accept non-trivial but inconsistent obligations and/or beliefs”. Here again this is an epistemic matter. More explicitly, it isn’t the case that we believe that “Cats have tails” and “Cats don’t have tails” at one and the same time. No one believes that an individual cat both has a tail and doesn’t have a tail. So, in that case, A works in one context; and ¬A works in another context. In other words, “cats have tails” (which, grammatically, doesn’t entail “All cats have tails”) is about cats in the plural; whereas any statement about an individual cat won’t be about all cats. Yet an individual cat both having and not having a tail means that the statements “Cats have tails” and “Cats don’t have tails” are both true. (This, admittedly, is also about cats in the plural.)

The existence of inconsistencies is also a matter of embracing Jaina values. After all, if a scientist accepts an inconsistent theory, that will partly be because for any given A (i.e., state of affairs) or p (i.e., statement or proposition) within that theory, it “maybe” or “maybe it is not”. Similarly, when it comes to p or A, “maybe it is, but it is not”. This results in also accepting Jaina value (4): “maybe it is indeterminate”. What’s more, if A or p is indeterminate, then it also follows that (5) “maybe it is but is indeterminate” and/or (6) “maybe it is not but is indeterminate”. That is, maybe A or p is; though it is still indeterminate to the theorist. Similarly, maybe A or p is not; though it is still indeterminate to the theorist.

In Priest’s terms, this truth-value indeterminacy (though p’s being indeterminate is itself be seen as a truth value) results in a scientific theory (or logical system) being inconsistent. And that inconsistency is a result of the logician or scientist being unable (at least at a given point in time) to erase certain inconsistencies from his system or theory. (This is something that’s often been said about Bohr’s well-known model of the atom.)

Despite all the above, deriving the notion of an inconsistent world from psychologistic and/or epistemological limitations (perhaps also from accepted notions in the philosophy of science) is problematic. Sure, this stress on the world here may betray a naïve, crude and, perhaps, old-fashioned view of logic. Having said that, Priest himself does mention the world (or “reality”) when he talks of consistency and inconsistency.

As it is, I simply can’t see how the world can be either inconsistent or consistent (see conclusion).

Graham Priest’s Boundary

It’s also helpful to apply Jaina seven-valued logic to an example which Graham Priest (again) discusses. Priest writes:

“Consider, for example, the boundary between the interior of a room (that which is in it) and the exterior (that which is not in it). If something is located on that boundary, is it in the room or not in it?”

Strangely enough, all the values of the Jaina system are helpful here. To spell the Jaina logic (as applied to a boundary) out in detail:

(1) Perhaps [or “maybe”] boundary x is in room 101.

(2) Perhaps boundary x is not in room 101.

(3) Perhaps we believe that boundary x is in room 101; but it is not in the room 101.

(4) Perhaps boundary x is indeterminate. [Or: Perhaps the answer to the question is indeterminate.]

(5) Perhaps boundary x is in room 101; but this is an indeterminate state of affairs.

(6) Perhaps boundary x is not in room 101; but this state of affairs is indeterminate. [Or: Perhaps the answer to the question may be indeterminate.]

(7) Perhaps boundary x is in room 101, boundary x is not in room 101, and this state of affairs is also indeterminate.

As stated earlier, values (1) to (5) are fairly (!) easy to comprehend. However, values (6) and (7) are problematic; at least as they’re expressed in this particular translation.

Priest himself offers us a dialethic solution (or answer) to the questions about this boundary. He writes:

“[T]he boundary is symmetrically placed with respect to each of its sides; so the only possibility that Reason countenances is a symmetric one. Thus, the object on the boundary of the room is both in it and not in it.”

Priest’s conclusion is equivalent to Jaina value (7). That is:

Perhaps boundary x is in room 101 and boundary x is not in room 101.

Jaina value (7) also has the clause “and this situation is also indeterminate” at the end of it. So what about boundary x being neither in room 101 nor outside room 101? This conclusion (kind of) deflates the dialethic conclusion in that rather than accepting the state of affairs that boundary x both is and is not in room 101, Jaina logic has it that an answer to this question is simply “indeterminate” (or “non-assertible”). This surely means that the Jaina position is far less (as it were) radical than Priest’s dialethic conclusion. Indeed one can even deflate the Jaina deflation itself and say that all that “indeterminate” means (in this instance at least) is that no answer will be (or can be) forthcoming — except, perhaps, via stipulation. If anything, the problem is “merely verbal” and it has no ontological import. (See David Chalmers on ‘Verbal Disputes — Questions of Language vs. Fact’ here.) In other words:

1) We can say that boundary x is in room 101.

2) We can say that boundary x is outside room 101.

3) And we can say that boundary x is neither in room 101 nor outside room 101.

The everyday definition of the word “boundary” has it that a boundary bounds something that isn’t itself part of the boundary. Nonetheless, a boundary can also be seen as being part of the something it bounds. For example, the boundary of the United Kingdom (or a football stadium) is part of the United Kingdom (or the football stadium). I believe that these conclusions square better with Jaina logic than with dialethic logic. After all, dialetheism has it that there are contradictions in the world; whereas Jaina logic simply says maybe this or maybe that (i.e., neither A nor ¬A are “assertible”).

Priest gives another example of “vague boundaries”: radioactive decay. He writes:

“[S]uppose that a radioactive atom instantaneously and spontaneously decays. At the instant of decay, is the atom integral or is it not?”

Priest continues:

“In both of these cases, and others like them, the law of excluded middle tells us that it is one or the other.”

What is Priest’s own logical conclusion when it comes to atomic decay? He claims that the aforementioned atom “at the point of decay is both integral and non-integral”. This isn’t allowed — Priest says — if the law of excluded middle is adhered to. The law of excluded middle tells us that the said atom must either be integral or non-integral; not both integral and non-integral.

This appears to be a temporal problem which must incorporate definitions — or philosophical accounts — of the concepts [instantaneously] and [spontaneously]. In other words, couldn’t the atom be neither integral nor non-integral when it instantaneously and spontaneously decays? Or, alternatively, at that point of decay, x (whatever it is) may not be an atom at all.

So what about the Liar sentence?

The fact that dialetheism might have been partly (or even largely) motivated by the well-known semantic paradoxes is relevant here. Take these two sentences; in which 1) is often taken to be the “formal” (or “syntactic”) expression of 2):

1) L: This sentence [L] is false.

2) [As said by a Cretan.] “All Cretans are liars.”

Like the boundary case, dialethic logicians argue that L is both true and false. Unlike the boundary example, however, this doesn’t seem to be a simple question of the merely verbal… That is, we can decide (or stipulate) as to whether or not a boundary x is inside or outside room 101. (Or we can argue that it is neither.) None of these things change reality in any way or even change how we perceive reality. At first glance, however, L doesn’t seem to be about reality at all. It’s a sentence which refers to itself. (Of course this sentence is also part of reality.) In that sense, the answer (or problem) seems to be purely formal or syntactic. Another way of putting this is to say that, unlike the boundary case, deciding whether or not L is true, false, true and false, or neither true nor false doesn’t seem to be a definitional (or stipulational) situation… Or is it? The way to answer questions about L is to go through the logic. When it comes to boundary x, on the other hand, it’s not clear that logic will help.

A & ¬A: Epistemic or Ontological?

|

| Graham Priest |

Jaina seven-valued logic seems less radical than dialethic logic. However, one can also give dialethic logic a purely epistemic (or deflationary) reading. Specifically, Priest’s position on Boolean negation may parallel (to some extent at least) to Jaina truth value (7). Namely: “ Maybe it is and it is not and is also indeterminate.” So perhaps “maybe it is not” isn’t actually a Boolean negation of the “maybe it is”. In other words, maybe it is something less than outright negation. Priest himself explains why that may be the case. He writes:

“Even dialetheists, after all, need to show that they don’t accept that 1 = 0. Now, if ¬A is compatible with A, then asserting ¬A cannot constitute a denial. To deny A one must assert something that is incompatible with it; so Boolean negation must make sense.”

Priest then offers a purely epistemic explanation of all this. He concludes:

“To deny A is simply to assert its negation. But this cannot be right. For example, we all, from time to time, discover that our views are, unwittingly, inconsistent. A serious of questions promps us to assert both A and ¬A. Is the second assertion a denial of A? Not at all; it is conveying the information that one accepts that ¬A, not that one does not accept A.”

This is primarily about belief, acceptance and consistency. It’s also about psychological states, judgements and logical (or scientific/theoretical) consistency. It’s not — at least not directly — about the world itself… Well, except that ontology (or what we say about the world) is dependent on our psychological states, beliefs and on logical (or scientific/theoretical) consistency. Yet if all this is correct, then not even dialethic logic is radical. In other words, dialethic logic is primarily a form of logic designed for the evaluation and logical systematisation of scientific theories. It’s also a logic of belief, judgements and — more generally — the relative merits of (the varying degrees of) consistency found in our logical, scientific, etc. systems.

The more radical and interesting aspect of dialethic logic is expressed by Priest in the following:

“A series of questions prompts us to assert both A and ¬A for some A.”

This seems to chime in with Jaina true value (7):

“ Maybe it is and it is not and is also indeterminate.”

In Priest’s example, perhaps it’s wise to assert both A and ¬A if both A and ¬A appear to be the case; or if both have (almost) equal evidential, logical and/or philosophical weight. And that goes for the Jaina locution, “ Maybe it is and it is not and is also indeterminate.” Nonetheless, at the end of the day most people (though not Jaina pluralists) would hope that either A or ¬A will prove to be the case (or perhaps simply become more acceptable). Our initial acceptance of A and ¬A, in other words, isn’t a commitment to the “inconsistency of the world” (as Priest puts it). And Jaina logic can be read as taking the position (which isn’t itself purely logical) that we can never know that the world itself is inconsistent. Priest, on the other hand, argues that contradictions exist in the world. Despite that, the position advanced in this piece is that our acceptance of [A & ¬A] tells us more about us than it does about the world.

So let Priest himself continue. He asks us this question:

“Is the second assertion [¬A] a denial of A?”

Yes, it seems so. Priest disagrees. Priest finishes off by saying that ¬A

“is conveying the information that one accepts ¬A, not that one does not accept A”.

In terms of classical logic, this is false. However, if we cite two propositions — then, yes, my acceptance of the proposition “Jones killed himself” doesn’t mean that I must also deny the proposition “Jones was shot”. (This isn’t Boolean negation.) In tandem with my remarks about equal evidential or logical/philosophical weight, my acceptance of “Jones killed himself” doesn’t mean that I will — or that I must — also deny the proposition that “Jones was shot”.

In addition, the proposition “Jones killed himself” isn’t a strict (or clear-cut) negation of “Jones was shot” (i.e., it's not a Boolean negation). A strict and clear-cut negation of “Jones was shot” would be “It’s not the case that Jones was shot”, not “Jones killed himself”. “Jones killed himself” can be seen as some sort of denial — or rejection — of the other proposition; though it’s not a strict Boolean negation. This rejection of Boolean negation appears to explain Priest’s acceptance of a dialethic… what?

In other words, if the symbolised state of affairs A ∧ ¬A is seen as including only the autonym A (i.e., a self-referential symbol without content), then clearly that statement can’t be accepted. Only they aren’t autonyms in Priest’s book. They are the dialethic acceptance of “contradictories” (i.e., symbols with worldly content).

Going back to the Priest quote directly above, one must now ask why a genuine (i..e, non-epistemic) dialetheist must reject 1 = 0. Isn’t accepting 1 = 0 at least one (logical) conclusion of dialetheism? However, if it’s incorrect to accept 1 = 0 (as Priest argues), then why is it correct to accept that boundary x both is inside and outside room 101? (Or that the Liar sentence is both true and false?) Why are numbers making all the difference here? Is it down to the simple identity sign (i.e., =) in the equation 1 = 0? That is, is it because we don’t say the following? -

1) L: This sentence [L] is true. = l: This sentence [L] is false.

2) Boundary x is in room 101.= Boundary x is not in room 101.

Does that make all the difference? Yet aren’t these identities at least implicit in the dialethic positions on the Liar sentence and on the boundary of room 101? In that case, what if we apply Gödel numbers to the boundary scenario? Thus:

i) Boundary x is inside room 101. = 1

ii) Boundary x is outside room 101. = 0

Thus, in dialethic logic, 1 = 0.

Conclusion: The Philosophy of Jaina and Dialethic Logics

|

| Anekāntavāda (“many-sidedness”) refers to the Jain doctrine about metaphysical truths that emerged in ancient India. It states that the ultimate truth and reality is complex and has multiple aspects. Anekantavada has also been interpreted to mean “non-absolutism”, “intellectual Ahimsa” and religious pluralism. |

The primary distinctions made above are between ontology and epistemology. Put simply, the seven-valued logic of the Jains is epistemological, not ontological. That is, it’s about what we know or can know, not about what is.

The overall position — and perhaps the Jaina position — on these issues is similar (or parallel) to Baruch Spinoza’s philosophical point that the world can only… be. Thus:

“I would warn you that I do not attribute to nature either beauty or deformity, order or confusion. Only in relation to our imagination can things be called beautiful or ugly, well-ordered or confused.”

The world itself can’t instantiate inconsistencies, let alone contradictions; though our systems and theories most certainly do. True; Priest explicitly states that it may be “rational to accept a contradiction”. He also goes on to say that

“there is nothing to stop the person accepting both their original view and the objection put to it, which is inconsistent with it”.

Yet talk of acceptance (or non-acceptance) seems psychologistic or epistemological in character, not logical and/or ontological. In other words, the predicaments of our epistemological and psychological positions shouldn’t be read into the world.

Yet one can also take an anti-realist and positive position on dialethic logic.

Since we only have access to the world via our contingent concepts, theories, systems, sensory receptors, etc., then that may impact on the issue of dialetheists embracing contradictions. That is, since some/many scientific, philosophical and logical theorists accept inconsistencies and even outright contradictions (for whichever reasons), then these systems and theories may pass on (as it were) their inconsistencies or contradictions to the world. In other words, if we get to the world through inconsistent or even contradictory theories and systems, then surely the world must itself be inconsistent or even instantiate contradictions.

Yet it needn’t be the case that an anti-realist should embrace contradictions or inconsistencies in the world. And that’s the case precisely because he’s an anti-realist. After all, if we can never know the world “as it is”, then how can we also know that the world instantiates inconsistencies or contradictions? Here again what we have is classic anti-realism: these inconsistencies or contradictions tell us more about us (or at least about our systems and theories) than they tell us about the world “as it is in itself”. So it may well be the case that we require inconsistent and even contradictory theories and systems to get at the world. However, that doesn’t tell is that the world itself is inconsistent or contradictory.